Zoologica Scripta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flyer200206 Parent

THE, FLYE, R Volume 26,25, NumberNumber 6 6 tuneJune 20022002 NEXT MEETING After scientists declared the Gunnison Sage Grouse a new species two years ago, a wide spot on Gun- Summer is here and we won't have meeting until a nison County (Colorado) Road 887, has become an Wednesday, 18. It begin September will atl:30 international bird-watching sensation. Birders from p.m. in Room 117 Millington Hall, on the William around the ,world wait silently in the cold dark of a campus. The editors'also get a summer &Mary Colorado spring pre-dawn to hear the "Thwoomp! vacation so there will be no July Flyer, but "God Thwoomp! Thwoomp!" of a male Gunnison Sage the creek rise," there be an willing and if don't will Grouse preparing to mate. The noise comes from August issue. specialized air sacs on the bird's chest. And this is now one stop on a well-traveled 1,000 mile circuit being traveled by birders wanting to add this Gun- RAIN CURTAILS FIELD TRIP TO nison bird, plus the Chukar, the Greater Sage YORK RIVER STATE PARK Grouse, the White-tailed Ptarmigan, the Greater Chicken Skies were threatening and the wind was fierce at Prairie and the Lesser Prairie Chicken to the beginning of the trip to the York River State their lii'e lists. Park on May 18. Despite all of that, leader Tom It was not always like this. Prior to the two-year- Armour found some very nice birds before the rains ago decision by the Ornithological Union that this came flooding down. -

Comments on the Ornithology of Nigeria, Including Amendments to the National List

Robert J. Dowsett 154 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(2) Comments on the ornithology of Nigeria, including amendments to the national list by Robert J. Dowsett Received 16 December 2014 Summary.—This paper reviews the distribution of birds in Nigeria that were not treated in detail in the most recent national avifauna (Elgood et al. 1994). It clarifies certain range limits, and recommends the addition to the Nigerian list of four species (African Piculet Verreauxia africana, White-tailed Lark Mirafra albicauda, Western Black-headed Batis Batis erlangeri and Velvet-mantled Drongo Dicrurus modestus) and the deletion (in the absence of satisfactory documentation) of six others (Olive Ibis Bostrychia olivacea, Lesser Short-toed Lark Calandrella rufescens, Richard’s Pipit Anthus richardi, Little Grey Flycatcher Muscicapa epulata, Ussher’s Flycatcher M. ussheri and Rufous-winged Illadopsis Illadopsis rufescens). Recent research in West Africa has demonstrated the need to clarify the distributions of several bird species in Nigeria. I have re-examined much of the literature relating to the country, analysed the (largely unpublished) collection made by Boyd Alexander there in 1904–05 (in the Natural History Museum, Tring; NHMUK), and have reviewed the data available in the light of our own field work in Ghana (Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2014), Togo (Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2011a) and neighbouring Benin (Dowsett & Dowsett- Lemaire 2011, Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2009, 2010, 2011b). The northern or southern localities of species with limited ranges in Nigeria were not always detailed by Elgood et al. (1994), although such information is essential for understanding distribution patterns and future changes. For many Guineo-Congolian forest species their northern limit in West Africa lies on the escarpment of the Jos Plateau, especially Nindam Forest Reserve, Kagoro. -

Does a Rival's Song Elicit Territorial Defense in a Tropical Songbird, The

ABC 2017, 4(2):146-153 Animal Behavior and Cognition https://doi.org/10.12966/abc.02.05.2017 ©Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) Does a Rival’s Song Elicit Territorial Defense in a Tropical Songbird, the Pied Bush Chat (Saxicola caprata)? Navjeevan Dadwal1* and Dinesh Bhatt1 1Gurukula Kangri University, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, India *Corresponding author (Email:[email protected]) Citation – Dadwal, N., & Bhatt, D. (2017). Does a rival’s song elicit territorial defense in a tropical songbird, the Pied Bush Chat (Saxicola caprata)? Animal Behavior and Cognition, 4(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.12966/ abc.02.05.2017 Abstract -The purpose of bird song and the way in which it is delivered has been argued to be adapted mainly for territorial defense. We performed a field experiment with the combination of playbacks and a model to test how much song actually relates to increased territorial defense in the territorial tropical songbird, the Pied Bush Chat, during breeding season (Feb–May, 2015) at Haridwar, Himalayan Foothills, India. As expected, the results of the experiment indicated that song was the major cue used by territory holders to cope with rival intrusions. The song rate was particularly escalated during simulated territorial interactions when the model was presented with a playback song of conspecifics. Behaviors such as restlessness (perch change), the height of perch, and distance from the model appeared to be of relatively lesser importance. To our knowledge, no avian species from the Indian subcontinent has been studied to provide evidence that song can escalate aggressive response by a territory owner. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Luscinia Luscinia)

Ornis Hungarica 2018. 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia) Tibor CSÖRGO˝ 1 , Péter FEHÉRVÁRI2, Zsolt KARCZA3, Péter ÓCSAI4 & Andrea HARNOS2* Received: April 20, 2018 – Revised: May 10, 2018 – Accepted: May 20, 2018 Tibor Csörgo,˝ Péter Fehérvári, Zsolt Karcza, Péter Ócsai & Andrea Harnos 2018. Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia). – Ornis Hungarica 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Abstract Ornithological studies often rely on long-term bird ringing data sets as sources of information. However, basic descriptive statistics of raw data are rarely provided. In order to fill this gap, here we present the seventh item of a series of exploratory analyses of migration timing and body size measurements of the most frequent Passerine species at a ringing station located in Central Hungary (1984–2017). First, we give a concise description of foreign ring recoveries of the Thrush Nightingale in relation to Hungary. We then shift focus to data of 1138 ringed and 547 recaptured individuals with 1557 recaptures (several years recaptures in 76 individuals) derived from the ringing station, where birds have been trapped, handled and ringed with standardized methodology since 1984. Timing is described through annual and daily capture and recapture frequencies and their descriptive statistics. We show annual mean arrival dates within the study period and present the cumulative distributions of first captures with stopover durations. We present the distributions of wing, third primary, tail length and body mass, and the annual means of these variables. -

New Birds in Africa New Birds in Africa

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 NEWNEW BIRDSBIRDS ININ AFRICAAFRICA 8 9 10 11 The last 50 years 12 13 Text by Phil Hockey 14 15 Illustrations by Martin Woodcock from Birds of Africa, vols 3 and 4, 16 reproduced with kind permission of Academic Press, and 17 David Quinn (Algerian Nuthatch) reproduced from Tits, Nuthatches & 18 Treecreepers, with kind permission of Russel Friedman Books. 19 20 New birds are still being discovered in Africa and 21 elsewhere, proof that one of the secret dreams of most birders 22 23 can still be realized. This article deals specifically with African discoveries 24 and excludes nearby Madagascar. African discoveries have ranged from the cedar forests of 25 northern Algeria, site of the discovery of the Algerian Nuthatch 26 27 (above), all the way south to the east coast of South Africa. 28 29 ome of the recent bird discoveries in Africa have come case, of their discoverer. In 1972, the late Dr Alexandre 30 Sfrom explorations of poorly-known areas, such as the Prigogine described a new species of greenbul from 31 remote highland forests of eastern Zaïre. Other new spe- Nyamupe in eastern Zaïre, which he named Andropadus 32 cies have been described by applying modern molecular hallae. The bird has never been seen or collected since and 33 techniques capable of detecting major genetic differences Prigogine himself subse- quently decided that 34 between birds that were previously thought to be races of the specimen was of a melanis- 35 the same species. The recent ‘splitting’ of the Northern tic Little Greenbul Andropadus 36 and Southern black korhaans Eupodotis afraoides/afra of virens, a species with a 37 southern Africa is one example. -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

Territoriality As a Paternity Guard in the European Robin, Erithacus Rubecula

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2000, 60, 165–173 doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1442, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on ARTICLES Territoriality as a paternity guard in the European robin, Erithacus rubecula JOE TOBIAS & NAT SEDDON Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge (Received 29 June 1999; initial acceptance 29 July 1999; final acceptance 18 March 2000; MS. number: 6273) To investigate the relative importance of paternity defences in the European robin we used behavioural observations, simulated intrusions and temporary male removal experiments. Given that paired males did not increase their mate attendance, copulation rate or territory size during the female’s fertile period, the most frequently quoted paternity assurance strategies in birds were absent. However, males with fertile females sang and patrolled their territories more regularly, suggesting that territorial motivation and vigilance were elevated when the risk of cuckoldry was greatest. In addition, there was a significant effect of breeding period on response to simulated intrusions: residents approached and attacked freeze-dried mounts more readily in the fertile period. During 90-min removals of the pair male in the fertile period, neighbours trespassed more frequently relative to prefertile and fertile period controls and appeared to seek copulations with unattended females. When replaced on their territories, males immediately increased both song rate and patrolling rate in comparison with controls. We propose that male robins sing to signal their presence, and increase their territorial vigilance and aggression in the fertile period to protect paternity. 2000 The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour Despite the apparent social monogamy of the majority of Thryothorus nigricapillus: Levin 1996). -

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6Th to 30Th January 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6th to 30th January 2018 (25 days) Trip Report Aardvark by Mike Bacon Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Wayne Jones Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Mega I 2018 2 Tour Summary The beauty of South Africa lies in its richness of habitats, from the coastal forests in the east, through subalpine mountain ranges and the arid Karoo to fynbos in the south. We explored all of these and more during our 25-day adventure across the country. Highlights were many and included Orange River Francolin, thousands of Cape Gannets, multiple Secretarybirds, stunning Knysna Turaco, Ground Woodpecker, Botha’s Lark, Bush Blackcap, Cape Parrot, Aardvark, Aardwolf, Caracal, Oribi and Giant Bullfrog, along with spectacular scenery, great food and excellent accommodation throughout. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Despite havoc-wreaking weather that delayed flights on the other side of the world, everyone managed to arrive (just!) in South Africa for the start of our keenly-awaited tour. We began our 25-day cross-country exploration with a drive along Zaagkuildrift Road. This unassuming stretch of dirt road is well-known in local birding circles and can offer up a wide range of species thanks to its variety of habitats – which include open grassland, acacia woodland, wetlands and a seasonal floodplain. After locating a handsome male Northern Black Korhaan and African Wattled Lapwings, a Northern Black Korhaan by Glen Valentine -

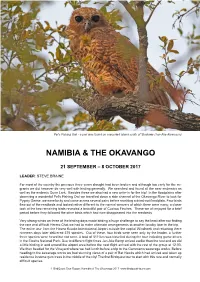

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Uganda: Comprehensive Custom Trip Report

UGANDA: COMPREHENSIVE CUSTOM TRIP REPORT 1 – 17 JULY 2018 By Dylan Vasapolli The iconic Shoebill was one of our major targets and didn’t disappoint! www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Uganda: custom tour July 2018 Overview This private, comprehensive tour of Uganda focused on the main sites of the central and western reaches of the country, with the exception of the Semliki Valley and Mgahinga National Park. Taking place during arguably the best time to visit the country, July, this two-and-a-half-week tour focused on both the birds and mammals of the region. We were treated to a spectacular trip generally, with good weather throughout, allowing us to maximize our exploration of all the various sites visited. Beginning in Entebbe, the iconic Shoebill fell early on, along with the difficult Weyns’s Weaver and the sought-after Papyrus Gonolek. Transferring up to Masindi, we called in at the famous Royal Mile, Budongo Forest, where we had some spectacular birding – White-spotted Flufftail, Cassin’s and Sabine’s Spinetails, Chocolate-backed and African Dwarf Kingfishers, White-thighed Hornbill, Ituri Batis, Uganda Woodland Warbler, Scaly-breasted Illadopsis, Fire-crested Alethe, and Forest Robin, while surrounding areas produced the sought-after White-crested Turaco, Marsh Widowbird, and Brown Twinspot. Murchison Falls followed and didn’t disappoint, with the highlights being too many to list all – Abyssinian Ground Hornbill, Black-headed Lapwing, and Northern Carmine Bee-eater all featuring, along with many mammals including a pride of Lions and the scarce Patas Monkey, among others. The forested haven of Kibale was next up and saw us enjoying some quality time with our main quarry, Chimpanzees. -

Siberian Blue Robin Larvivora Cyane from the Barak Valley of Assam with a Status Update for India

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338137338 Siberian Blue Robin Larvivora cyane from the Barak Valley of Assam with a status update for India Article in Indian BIRDS · December 2019 CITATIONS READS 0 7 2 authors: Rejoice Gassah Vijay Anand Ismavel Makunda Christian Hospital 4 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS 22 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Neglected health problems in rural India View project Biodiversity Documentation View project All content following this page was uploaded by Vijay Anand Ismavel on 24 December 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Correspondence 123 peninsular India (Grimmett et al. 2011; Rasmussen & Anderton minY=11.103753465762485&env.maxX=93.01342361450202&env.maxY=12.31963 2012; eBird 2019). This species is a common winter visitor to 3103994705&zh=true&gp=true&ev=Z&mr=on&bmo=1&emo=1&yr=cur&byr=2019 Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Tonkin (Robson 2008). &eyr=2019. [Accessed on: 19 January 2019.] DeCandido, R., Subedi, T., Siponen, M., Sutasha, K., Pierce, A., Nualsri, C., & Round, P. D., 2013. Flight identification of Milvus migrans lineatus ‘Black-eared’ Kite and Milvus migrans govinda ‘Pariah’ Kite in Nepal and Thailand. BirdingASIA 20: 32–36. Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 2011. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press & Christopher Helm. Pp. 1–528. Rasmussen, P. C., & Anderton, J. C., 2012. Birds of South Asia: the Ripley guide: field guide. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.