Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE of CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 a Look at the Golden Bears

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 A Look at the Golden Bears ....................................................... 2-3 Enrollment: 33,000 Scouting Report .............................................................................. 4 Colors: Blue (282) & Gold (116) Golden Bear Notes ...................................................................... 5-8 Nickname: Golden Bears 2006 NCAA Tournament Bracket ................................................ 9 Chancellor: Dr. Robert Birgeneau Cal vs. NCAA Tournament Field ................................................ 10 Athletic Director: Sandy Barbour Arena: Walter A. Haas Jr. Pavilion (11,877) Cal in Postseason Play ............................................................ 11-13 Conference: Pacific-10 NCAA Tournament Records .................................................. 14-15 NCAA Tournament Appearances: 14 Head Coach Ben Braun ........................................................... 16-17 1946, ’57, ’58, ’59, ’60, ’90, ’93, ’94, ’96, ’97, 2001, ’02, ’03, ’06 Assistant Coaches ........................................................................ 18 NCAA Final Four Appearances: 3 2005-06 Player Profiles .......................................................... 19-32 1946 (4th), 1959 (1st), 1960 (2nd) Pacific-10 Standings & Honors .................................................... 33 2005-06 Record: 20-10 2005-06 Pac-10 Record/Finish: 12-6/3rd 2005-06 Cumulative Stats ........................................................... -

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 A.M

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 a.m. ET ............Al Skinner, Boston College 10:40 a.m. ET ............Oliver Purnell, Clemson 10:50 a.m. ET ............Mike Krzyzewski, Duke 11:00 a.m. ET ............Leonard Hamilton, Florida State 11:10 a.m. ET ............Paul Hewitt, Georgia Tech 11:20 a.m. ET ............Gary Williams, Maryland 11:30 a.m. ET ............Frank Haith, Miami 11:40 a.m. ET ............Roy Williams, North Carolina 11:50 a.m. ET ............Sidney Lowe, N.C. State 12:00 p.m. ET ............Tony Bennett, Virginia 12:10 p.m. ET ............Seth Greenberg, Virginia Tech 12:20 p.m. ET ............Dino Gaudio, Wake Forest ATLANTIC 10 CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 15) 10:10 a.m. ET ............Bobby Lutz, Charlotte 10:17 a.m. ET ............Chris Mooney, Richmond 10:24 a.m. ET ............Chris Mack, Xavier 10:31 a.m. ET ............Mark Schmidt, St. Bonaventure 10:38 a.m. ET ............Brian Gregory, Dayton 10:45 a.m. ET ............John Giannini, La Salle 10:52 a.m. ET ............Fran Dunphy, Temple 10:59 a.m. ET ............Derek Kellogg, Massachusetts 11:06 a.m. ET ............Karl Hobbs, George Washington 11:13 a.m. ET ............Ron Everhart, Duquesne 11:20 a.m. ET ............Rick Majerus, Saint Louis 11:27 a.m. ET ............Jared Grasso, Fordham 11:34 a.m. ET ............Jim Baron, Rhode Island 11:41 a.m. ET ............Phil Martelli, Saint Joseph’s BIG EAST CONFERENCE Thursday (Jan. 7, Jan. 21, Feb. 4, Feb. 18) 11:00 a.m. ET ............Jay Wright, Villanova 11:08 a.m. -

Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992 University of Montana Publications 1-1-1967 Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968 University of Montana (Missoula, Mont. : 1965-1994). Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlybasketball_yearbooks_asc Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana (Missoula, Mont. : 1965-1994). Athletics Department, "Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1967-1968" (1967). Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992. 4. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlybasketball_yearbooks_asc/4 This Yearbook is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grizzly Basketball Yearbook, 1955-1992 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES Grizzly Basketball 1 9 6 7 -6 8 University of Montana UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA GENERAL INFORMATION Founded ____________,__________________ ._____ 1893 E nrollm ent_________________________________ 6,500 President______________________ Robert T. Pantzer Nicknames___ ________________ Grizzlies, Silvertips C olors___________________ Copper, Silver and Gold ATHLETIC STAFF Athletic D irector__________________ Jack Swarthout Faculty Representative............ __Dr. Earl Lory Head Basketball Coach_________________ Ron Nord Assistant Basketball -

Mississippi State 2020-21 Basketball

11 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES 1963 • 1991 • 1995 • 1996 • 2002 • 2003 MISSISSIPPI STATE 2004 • 2005 • 2008 • 2009 • 2019 MEN’S BASKETBALL CONTACT 2020-21 BASKETBALL MATT DUNAWAY • [email protected] OFFICE (662) 325-3595 • CELL (727) 215-3857 Mississippi State (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) vs. Auburn (12-14 • 6-11 SEC) GAME 27 • AUBURN ARENA • AUBURN, ALABAMA • SATURDAY, MARCH 6 • 12:00 P.M. CT 27 TV: SEC NETWORK • WATCH ESPN APP • RADIO: 100.9 WKBB-FM • STARKVILLE • ONLINE: HAILSTATE.COM • TUNE-IN RADIO APP MISSISSIPPI STATE (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) MISSISSIPPI STATE POSSIBLE STARTING LINEUP • BASED ON PREVIOUS GAMES H: 9-6 • A: 5-3 • N: 0-3 • OT: 0-2 NO. 1 IVERSON MOLINAR • G • 6-3 • 190 • SO. • PANAMA CITY, PANAMA NOVEMBER • 1-2 2020-21 • 16.3 PPG • 140-297 FG • 32-71 3-PT FG • 64-80 FT • 3.9 RPG • 2.6 APG • 1.1 SPG Space Coast Challenge • Melbourne, Florida • Nov. 25-26 Wed. 25 vs. Clemson • CBS-SN L • 53-42 LAST GAME • AT TEXAS A&M • 18 PTS • 7-12 FG • 2-5 3-PT FG • 2-4 FT • 5 REB • 3 ASST • 1 STL Thur. 26 vs. Liberty • CBS-SN L • 84-73 • Molinar is an explosive combo guard who is a talented shooter, passer and slasher that can get to the rim • 16.3 PPG is 6th in the SEC (03/06) Mon. 30 Texas State • SECN W • 68-51 • Dialed up career-high 24 PTS at UGA (12/30) and at VANDY (01/09) • Howland: Molinar’s jump from FR/SOPH reminds him of Russell Westbrook at UCLA DECEMBER • 5-1 • 10+ PTS in 20 of his 23 outings and 6 GMS of 20+ PTS in 2020-21 • His +10.4 PPG is T-8th largest FR/SOPH scoring jump in SEC over last decade Fri. -

Montana Kaimin, February 7, 2018 Students of the University of Montana, Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 2-7-2018 Montana Kaimin, February 7, 2018 Students of the University of Montana, Missoula Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Students of the University of Montana, Missoula, "Montana Kaimin, February 7, 2018" (2018). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6957. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6957 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montana Kaimin IN THE RED How UM Dining’s upscale restaurant poured nearly $1 million down the drain NEWS Muslim students SPORTS How Griz OPINION What to do searched by police basketball stays on top with all those textbooks Issue No. 15 February 7, 2018 KIOSK ON THE COVER PHOTO ILLUSTRATIONWeek LACEY of YOUNG2/5/18 AND - REED2/11/18 KLASS HELP WANTED The Montana Kaimin is a weekly independent student newspaper at the University MEDIA TECHNICAL SPECIALIST – Missoula County Public Schools of Montana. Apply now for this full time, 200 days/9 holidays position! For comments, corrections or letters to the editor, contact editor@ by Margie E. Burke The Weekly Crossword $15.44 to 16.94 per hour depending on placement on the wage montanakaimin.com or call (406) 243-4310. -

Coach Wayne Tinkle I Think Early on We Were a Little Caught in the Moment

NCAA Men's Basketball Championship: Regional Semifinal: Oregon St. vs Loyola Chicago Saturday, March 27, 2021 Indianapolis, Indiana, USA COACH TINKLE: We're playing with a lot of confidence on Bankers Life Fieldhouse both ends. And we're a pretty darned good defensive Oregon State Beavers team. And we showed that. And then timely baskets. Coach Wayne Tinkle I think early on we were a little caught in the moment. We weren't as sharp offensively, plus they're really good Sweet 16 Postgame Media Conference defensively. We heard about that and saw it in all the tape we watched. But we settled in. And there's no doubt in our guys' minds. They really Oregon State - 65, Loyola Chicago - 58 believe that this is their time. It's what we said before we left the locker room, that we're not going to get rattled. COACH TINKLE: All I want to say is can we cut in? That's This is our time. It's meant to be. Let's go play ball. And it. Go ahead, fire away. like I said, they were all very, very calm through it all. Q. Wayne, Ethan just seemed like he was calm out Q. You've been coaching a long time. This is one of there and just in control of everything. Where does the most historic runs in the history of the school. that come from? Where did it come from today and What's it like for you personally to be right in the where has it been coming from of late? middle of this and being a leader on the team? COACH TINKLE: I think he's a senior. -

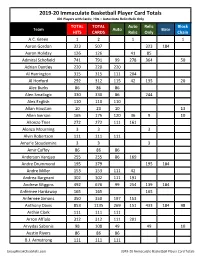

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals 401 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 1 2 1 1 Aaron Gordon 323 507 323 184 Aaron Holiday 126 126 41 85 Admiral Schofield 741 791 99 278 364 50 Adrian Dantley 220 220 220 Al Harrington 315 315 111 204 Al Horford 292 312 115 42 135 20 Alec Burks 86 86 86 Alen Smailagic 330 330 86 244 Alex English 110 110 110 Allan Houston 10 23 10 13 Allen Iverson 165 175 120 36 9 10 Allonzo Trier 272 272 111 161 Alonzo Mourning 3 3 3 Alvin Robertson 111 111 111 Amar'e Stoudemire 3 3 3 Amir Coffey 86 86 86 Anderson Varejao 255 255 86 169 Andre Drummond 195 379 195 184 Andre Miller 153 153 111 42 Andrea Bargnani 302 302 111 191 Andrew Wiggins 492 676 99 254 139 184 Anfernee Hardaway 165 165 165 Anfernee Simons 350 350 197 153 Anthony Davis 853 1135 269 151 433 184 98 Archie Clark 111 111 111 Arron Afflalo 312 312 111 201 Arvydas Sabonis 98 108 49 49 10 Austin Rivers 86 86 86 B.J. Armstrong 111 111 111 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bam Adebayo 163 347 163 184 Baron Davis 98 118 98 20 Ben Simmons 206 390 5 201 184 Bernard King 230 233 230 3 Bill Laimbeer 4 4 4 Bill Russell 104 117 104 13 Bill Walton 35 48 35 13 Blake Griffin 318 502 5 313 184 Bob McAdoo 49 59 49 10 Boban Marjanovic 264 264 111 153 Bogdan Bogdanovic 184 190 141 42 1 6 Bojan Bogdanovic 247 431 247 184 Bol Bol 719 768 99 287 333 -

Chapter 15 - Red Cedar Rebounds

Chapter 15 - Red Cedar Rebounds You cannot step twice into the same river. Heraclitus (circa 535 BC – 475 BC) While Heraclitus posited that “you cannot step twice into the same river,” the question is whether one tries a first time step into life’s river of challenges. For centuries the Red Cedar River has flowed from points east of Okemos, through Okemos and the campus of Michigan State University, and onward to points west. But, over the past half-century, only a select group of Okemos High Chieftain basketball players realized their dream of grabbing a rebound on the Chieftains home court and moving the basketball from the Chieftains O-ZONE to the Spartans IZZONE to become a Michigan State Spartan. Yet one Chieftain-cum-Spartan – Kristen Rasmussen – did step twice into the Red Cedar to return to the basketball court on which she once played Chieftain basketball and serve as head coach of the Okemos High girls’ basketball program. Over the past 60 seasons of Spartans basketball (‘60-61 to ’19-‘20), only 14 Chieftain basketball players traveled down the Red Cedar to change their uniforms from Maroon and White of the Chieftains to the Green and White of the Spartans, this happening when they stepped onto the court of Jenison Field House or the Breslin Center The “Time Line” graphics on the next two pages show the seasons in which Okemos High Chieftains were members of a Michigan State University Spartans basketball squad, with the second graphic showing the seasons (maroon) in which a Spartans basketball squad had no Chieftain. -

Men's Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall Series Began 1912-13

Men’s Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall series began 1912-13 Beckleheimer NOTE Beckleheimer was a three sport letterwinner at Morris Harvey College. Possibly the first in school history. 1913-14 5-3 Wesley Alderman ROSTER C. Fulton, Taylor, B. Fulton, Jack Latterner, Beckelheimer, Bolden, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Marshall, (19-42). NOTE According to the 1914 Yearbook: “Latterner best basketball man in the state” PHOTO Team photo: 1914 Yearbook, pg. 107 flickr.com UC sports archives 1917-18 8-2 Herman Beckleheimer ROSTER Golden Land, Walter Walker HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Swept Marshall 1918-19 ROSTER Watson Haws, Rollin Withrow, Golden Land, Walter Walker 1919-20 11-10 W.W. Lovell ROSTER Watson Haws 188 points Golden Land Hollis Westfall Harvey Fife Rollin Withrow Jones, Cano, Hansford, Lambert, Lantz, Thompson, Bivins NOTE Played first full college schedule. (Previous to this season, opponents were a mix from colleges, high schools and independent teams.) 1920-21 8-4 E.M. “Brownie” Fulton ROSTER Land, Watson Haws, Lantz, Arthur Rezzonico, Hollis Westfall, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Won two out of three vs. Marshall, (25-21, 33-16, 21-29) 1921-22 5-9 Beckleheimer ROSTER Watson Haws, Lantz, Coon, Fife, Plymale, Hollis Westfall, Shannon, Sayre, Delaney HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Virginia Tech, (22-34) PHOTO Team photo: The Lamp, May 1972, pg. 7 Watson Haws: The Lamp, May 1972, front cover 1922-23 4-11 Beckleheimer ROSTER H.C. Lantz, Westfall, Rezzonico, Leman, Hager, Delaney, Chard, Jones, Green. PHOTO Team photo: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 107 Individual photos: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 109 1923-24 ROSTER Lantz, Rezzonico, Hager, King, Chard, Chapman NOTE West Virginia Conference first year, Morris Harvey College one of three charter members. -

When the Game Was Ours

When the Game Was Ours Larry Bird and Earvin Magic Johnson Jr. With Jackie MacMullan HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT BOSTON • NEW YORK • 2009 For our fans —LARRY BIRD AND EARVIN "MAGIC" JOHNSON JR. To my parents, Margarethe and Fred MacMullan, who taught me anything was possible —JACKIE MACMULLAN Copyright © 2009 Magic Johnson Enterprises and Larry Bird ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003. www.hmhbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bird, Larry, date. When the game was ours / Larry Bird and Earvin Magic Johnson Jr. with Jackie MacMullan. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-547-22547-0 1. Bird, Larry, date 2. Johnson, Earvin, date 3. Basketball players—United States—Biography. 4. Basketball—United States—History. I. Johnson, Earvin, date II. MacMullan, Jackie. III. Title. GV884.A1B47 2009 796.3230922—dc22 [B] 2009020839 Book design by Brian Moore Printed in the United States of America DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Introduction from LARRY WHEN I WAS YOUNG, the only thing I cared about was beating my brothers. Mark and Mike were older than me and that meant they were bigger, stronger, and better—in basketball, baseball, everything. They pushed me. They drove me. I wanted to beat them more than anything, more than anyone. But I hadn't met Magic yet. Once I did, he was the one I had to beat. What I had with Magic went beyond brothers. -

Friday, November 11 Erb Memorial Union, 107 Charles Miller Leadership Room*

Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon Executive and Audit Committee Public Meeting 1:30 pm – Friday, November 11 Erb Memorial Union, 107 Charles Miller Leadership Room* Convene - Call to order, roll call 1. Approval of Certain Athletic Contract (Men’s Basketball, head coach): Rob Mullens, Director of Intercollegiate Athletics Meeting Adjourns *This will be a telephonic meeting of the committee. A location is provided for members of the public who wish to listen to the proceedings. BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6227 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403-1266 T (541) 346-3166 trustees.uoregon.edu An equal-opportunity, affirmative-action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act Agenda Item #1 Audited FY16 Financial Statements Page 1 of 22 Certain Employment Contract Dana Altman (Head Coach Men’s Basketball) Board of Trustees approval is sought for an employment contract within the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (Athletics). Although employment matters are delegated to the University President, the Board has retained authority over contracts and instruments with an anticipated value reasonably expected to reach or exceed $5,000,000. Athletics has reached agreement for a renegotiated seven‐year contract with Dana Altman, head coach of men’s basketball, the aggregate value of which will exceed $5,000,000. Attached is a list of comparative salaries indicating Altman’s relative placement. Below is a brief summary of key economic terms: Term 7 years l(Apri 26, 2016‐April 25, 2023)