Style Architecture of Cusco, Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quispe Pacco Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL DISTRITO DE NUÑOA TESIS PRESENTADA POR: SANDRO QUISPE PACCO PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN EDUCACIÓN CON MENCIÓN EN LA ESPECIALIDAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES PROMOCIÓN 2016- II PUNO- PERÚ 2017 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SEUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL D ���.r NUÑOA SANDRO QUISPE PACCO APROBADA POR EL SIGUIENTE JURADO: PRESIDENTE e;- • -- PRIMER MIEMBRO --------------------- > '" ... _:J&ª··--·--••__--s;; E • Dr. Jorge Alfredo Ortiz Del Carpio SEGUNDO MIEMBRO --------M--.-S--c--. --R--e-b-�eca Alano�ca G�u�tiérre-z-- -----�--- f DIRECTOR ASESOR ------------------ , M.Sc. Lor-- �VÍlmore Lovón -L-o--v-ó--n-- ------------- Área: Disciplinas Científicas Tema: Patrimonio Histórico Cultural DEDICATORIA Dedico este informe de investigación a Dios, a mi madre por su apoyo incondicional, durante estos años de estudio en el nivel pregrado en la UNA - Puno. Para todos con los que comparto el día a día, a ellos hago la dedicatoria. 2 AGRADECIMIENTO Mi principal agradecimiento a la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano – Puno primera casa superior de estudios de la región de Puno. A la Facultad de Educación, en especial a los docentes de la especialidad de Ciencias Sociales, que han sido parte de nuestro crecimiento personal y profesional. A mi familia por haberme apoyado económica y moralmente en -

Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley — Lima, Cusco, Machu Picchu, Sacred Valley of the Incas — TOUR DETAILS Machu Picchu & Highlights The Sacred Valley • Machu Picchu • Sacred Valley of the Incas • Price: $1,995 USD • Vistadome Train Ride, Andes Mountains • Discounts: • Ollantaytambo • 5% - Returning Volant Customer • Saqsaywaman • Duration: 9 days • Tambomachay • Date: Feb. 19-27, 2018 • Ruins of Moray • Difficulty: Easy • Urumbamba River • Aguas Calientes • Temple of the Sun and Qorikancha Inclusions • Cusco, 16th century Spanish Culture • All internal flights (while on tour) • Lima, Historic Old Town • All scheduled accommodations (2-3 star) • All scheduled meals Exclusions • Transportation throughout tour • International airfare (to and from Lima, Peru) • Airport transfers • Entrance fees to museums and other attractions • Machu Picchu entrance fee not listed in inclusions • Vistadome Train Ride, Peru Rail • Personal items: Laundry, shopping, etc. • Personal guide ITINERARY Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley - 9 Days / 8 Nights Itinerary - DAY ACTIVITY LOCATION - MEALS Lima, Peru • Arrive: Jorge Chavez International Airport (LIM), Lima, Peru 1 • Transfer to hotel • Miraflores and Pacific coast Dinner Lima, Peru • Tour Lima’s Historic District 2 • San Francisco Monastery & Catacombs, Plaza Mayor, Lima Cathedral, Government Palace Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Ollyantaytambo, Sacred Valley • Morning flight to Cusco, The Sacred Valley of the Incas 3 • Inca ruins: Saqsaywaman, Rodadero, Puca Pucara, Tambomachay, Pisac • Overnight: Ollantaytambo, Sacred -

Exploring How Things Take Shape Research Notes on Ethnography, Empirical Sensibility and the Baroque State

Exploring How Things Take Shape Research Notes on Ethnography, Empirical Sensibility and the Baroque State. Penny Harvey - University of Manchester The Historical Baroque in Contemporary Peru - Illusion and Enthrallment The main square of Cusco was unusually busy and more unusual still the huge doors of the Cathedral were open, people pouring out from what must have been an important mass. Taking advantage of a rare opportunity to visit this building outside of the normal restrictions imposed by the tourist trade, I ducked in through a side entrance just as the main doors were slammed shut again. It was years since I‟d been inside and I‟d forgotten the sheer scale and intricacy of the space. The Cathedral over-awes as intended. Throughout the Continent these huge, ambitious spaces were of central importance in marking Spanish presence, in imposing Catholicism, in erasing the presence and influence of previous Gods and divine rulers, and paradoxically in offering people some kind of solace. This Cathedral was no exception. To build it the Spanish had destroyed an Inka palace/ceremonial site which nevertheless provided the foundations for the new building. They also brought stone from the fortress of Sacsayhuaman subjugating the very fabric of the Inka imperial capital in its public conversion to Catholicism. Construction had begun in 1560 but was not completed until 1664. The building itself presents the non-coherence of architectural style that is characteristic of many of these mega projects that took over a century to be finalised. In this case the Renaissance facade constrasts with the interior, funished over a century later, by then exemplifying the colonial Baroque with its intricate gold and silver altars, carved stone work and the world famous collection of paintings of what became known as the Cusco school. -

Ohio's State Tests

Ohio’s State Tests PRACTICE TEST GRADE 8 ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS Student Name The Ohio Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, or disability in employment or the provision of services. Some items are reproduced with permission from the American Institutes for Research as copyright holder or under license from third parties. Copyright © 2017 by the Ohio Department of Education. All rights reserved. Directions: Today you will be taking the Ohio Grade 8 English Language Arts Practice Assessment. There are several important things to remember: 1. Read each question carefully. Think about what is being asked. Look carefully at graphs or diagrams because they will help you understand the question. Then, choose or write the answer you think is best in your Answer Document. 2. Use only a #2 pencil to answer questions on this test. 3. For questions with bubbled responses, choose the correct answer and then fill in the circle with the appropriate letter in your Answer Document. Make sure the number of the question in this Student Test Booklet matches the number in your Answer Document. If you change your answer, make sure you erase your old answer completely. Do not cross out or make any marks on the other choices. 4. For questions with response boxes, write your answer neatly, clearly and only in the space provided in your Answer Document. Any responses written in your Student Test Booklet will not be scored. Make sure the number of the question in this Student Test Booklet matches the number in your Answer Document. -

Pscde3 - the Four Sides of the Inca Empire

CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. Manco Cápac 515 – Wanchaq Ca. M. M. Izaga 740 Of. 207 - Chiclayo www.chaskiventura.com T: 51+ 84 233952 T: 51 +74 221282 PSCDE3 - THE FOUR SIDES OF THE INCA EMPIRE SUMMARY DURATION AND SEASON 15 Days/ 14 Nights LOCATION Department of Arequipa, Puno, Cusco, Raqchi community ATRACTIONS Tourism: Archaeological, Ethno tourism, Gastronomic and landscapes. ATRACTIVOS Archaeological and Historical complexes: Machu Picchu, Tipón, Pisac, Pikillaqta, Ollantaytambo, Moray, Maras, Chinchero, Saqsayhuaman, Catedral, Qoricancha, Cusco city, Inca and pre-Inca archaeological complexes, Temple of Wiracocha, Arequipa and Puno. Living culture: traditional weaving techniques and weaving in the Communities of Chinchero, Sibayo, , Raqchi, Uros Museum: in Lima, Arequipa, Cusco. Natural areas: of Titicaca, highlands, Colca canyon, local fauna and flora. TYPE OF SERVICE Private GUIDE – TOUR LEADER English, French, or Spanish. Its presence is important because it allows to incorporate your journey in the thematic offered, getting closer to the economic, institutional, and historic culture and the ecosystems of the circuit for a better understanding. RESUME This circuit offers to get closer to the Andean culture and to understand its world view, its focus, its technologies, its mixture with the Hispanic culture, and the fact that it remains present in Indigenous Communities today. In this way, by bus, small boat, plane or walking, we will visit Archaeological and Historical Complexes, Communities, Museums & Natural Environments that will enable us to know the heart of the Inca Empire - the last heir of the Andean independent culture and predecessor of the mixed world of nowadays. CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

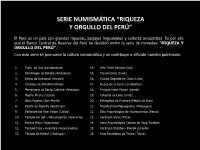

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

REVIS. ILLES I IMPERIS14(2GL)1 19/12/11 09:08 Página 87

REVIS. ILLES I IMPERIS14(2GL)1 19/12/11 09:08 Página 87 ALONSO DE SOLÓRZANO Y VELASCO Y EL PATRIOTISMO LIMEÑO (SIGLO XVII) Alexandre Coello de la Rosa Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF) [email protected] ¡Profundamente lo ponderó [Marco Tulio] Cicerón, o achaque enve- jecido de la naturaleza, que a vista de la pureza, no faltan colores a la emulación! Sucede lo que al ave, toda vestida de plumaje, blanco (ar- miño alado) que vuela a la suprema región del aire, y a los visos del Sol parece que mil colores le acentúan la pluma. Apenas pretende el criollo ascender con las alas, que le dan sus méritos, cuando buscan- do colores, aunque a vista del Sol les pretender quebrar las alas, por- que no suban con ellas a la región alta del puesto de su patria.1 Estas palabras, escritas en 1652 por el oidor de la Audiencia de Lima y rector de la Uni- versidad Mayor de San Marcos, don Alonso de Solórzano y Velasco (1608-1680), toda- vía destilan parte de su fuerza y atrevimiento. A principios del siglo XVII la frustración de los grupos criollos más ilustres a los que se impedía el acceso a los empleos y honores reales del Virreinato peruano, en beneficio de los peninsulares, despertó un sentimiento de autoafirmación limeña.2 La formación de ese sentimiento de identidad individual fa- voreció que los letrados capitalinos, como Solórzano y Velasco, redactaran discursos y memoriales a través de los cuales se modelaron a sí mismos como «sujetos imperiales» con derecho a ostentar honores y privilegios.3 Para ello evocaron la idea de «patria» como una estrategia colectiva de replantear las relaciones contractuales entre el «rey, pa- dre y pastor» y sus súbditos criollos.4 1. -

Lost Ancient Technology of Peru and Bolivia

Lost Ancient Technology Of Peru And Bolivia Copyright Brien Foerster 2012 All photos in this book as well as text other than that of the author are assumed to be copyright free; obtained from internet free file sharing sites. Dedication To those that came before us and left a legacy in stone that we are trying to comprehend. Although many archaeologists don’t like people outside of their field “digging into the past” so to speak when conventional explanations don’t satisfy, I feel it is essential. If the engineering feats of the Ancient Ones cannot or indeed are not answered satisfactorily, if the age of these stone works don’t include consultation from geologists, and if the oral traditions of those that are supposedly descendants of the master builders are not taken into account, then the full story is not present. One of the best examples of this regards the great Sphinx of Egypt, dated by most Egyptologists at about 4500 years. It took the insight and questioning mind of John Anthony West, veteran student of the history of that great land to invite a geologist to study the weathering patterns of the Sphinx and make an estimate of when and how such degradation took place. In stepped Dr. Robert Schoch, PhD at Boston University, who claimed, and still holds to the theory that such an effect was the result of rain, which could have only occurred prior to the time when the Pharaoh, the presumed builders, had existed. And it has taken the keen observations of an engineer, Christopher Dunn, to look at the Great Pyramid on the Giza Plateau and develop a very potent theory that it was indeed not the tomb of an egotistical Egyptian ruler, as in Khufu, but an electrical power plant that functioned on a grand scale thousands of years before Khufu (also known as Cheops) was born. -

© Hachette Tourisme 2011 TABLE DES MATIÈRES

© Hachette Tourisme2011 © Hachette Tourisme 2011 TABLE DES MATIÈRES LES QUESTIONS QU’ON SE POSE LE PLUS SOUVENT ....... 12 LES COUPS DE CŒUR DU ROUTARD ................................................. 13 COMMENT ALLER AU PÉROU ET EN BOLIVIE ? G LES LIGNES RÉGULIÈRES ............ 14 G DEPUIS LES PAYS G LES ORGANISMES DE VOYAGES ..... 14 LIMITROPHES ....................................... 38 GÉNÉRALITÉS COMMUNES AUX DEUX PAYS G AVANT LE DÉPART ............................ 40 G HISTOIRE CONTEMPORAINE ....... 59 G ARGENT, BANQUES, CHANGE .... 42 G ITINÉRAIRES ......................................... 59 G ART TEXTILE ......................................... 43 G LAMAS ET Cie ....................................... 60 G COCA ......................................................... 44 G LANGUE ................................................... 61 G CONSEILS DE VOYAGE G PHOTO ...................................................... 63 (EN VRAC) ............................................... 46 G RELIGIONS ET CROYANCES ........ 64 G COURANT ÉLECTRIQUE ................. 47 G SANTÉ ....................................................... 66 G GÉOGRAPHIE ....................................... 47 G TREKKING – RANDONNÉES ......... 68 G HISTOIRE ................................................. 49 G UNITAID .................................................... 70 PÉROU UTILE G ABC DU PÉROU ................................... 71 G DÉCALAGE HORAIRE ...................... 80 G AVANT LE DÉPART ............................ 71 G FÊTES ET JOURS FÉRIÉS ............. -

Visitantes Del Museo De La Inquisición

ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DE LOS MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ (1992 - 2018) ÍI,� tq -- ESTADÍSTICAS DE VISITANTES DEL MUSEO DEL CONGRESO Y DE LA INQUISICIÓN Y DE LOS PRINCIPALES MUSEOS Y SITIOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS DEL PERÚ ÍNDICE Introducción P. 2 Historia del Museo Nacional del Perú P. 3 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 19 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo Nacional Afroperuano del P. 22 Congreso Estadísticas del Sitio Web del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 23 Estadísticas de visitantes del Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición P. 29 Estadísticas de visitantes del Palacio Legislativo P. 40 Estadísticas de visitantes de los principales museos y sitios P. 42 arqueológicos del Perú 1 INTRODUCCIÓN El Museo del Congreso tiene como misión investigar, conservar, exhibir y difundir la Historia del Congreso de la República y el Patrimonio Cultural a su cargo. Actualmente, según lo dispuesto por la Mesa Directiva del Congreso de la República, a través del Acuerdo de Mesa N° 139-2016-2017/MESA-CR, comprende dos museos: Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición Fue establecido el 26 de julio de 1968. Está ubicado en la quinta cuadra del Jr. Junín s/n, en el Cercado de Lima. Funciona en el antiguo local del Senado Nacional, el que durante el Virreinato había servido de sede al Tribunal de la Inquisición. El edificio es un Monumento Nacional y forma parte del patrimonio cultural del país. Además, ha estado vinculado al Congreso de la República desde los días del primer Congreso Constituyente del Perú, cuando en sus ambientes se reunían sus miembros, alojándose inclusive en él numerosos Diputados. -

Visitantes Del Museo De La Inquisición

INTRODUCCIÓN El Museo del Congreso y de la Inquisición ofrece a sus usuarios, y al público interesado en general, las cifras estadísticas de sus actividades así como las referidas a la cantidad de visitantes asistentes a los museos y sitios arqueológicos de nuestro país. De esta forma buscamos facilitar el acceso a la información sobre uno de los aspectos más importantes de la realidad museística y que, en alguna forma, resume la relación entre el público y los museos. Algunos escritores, como Carlos Daniel Valcárcel, basándose en las referencias de los cronistas, sostienen que el antecedente más remoto de los museos peruanos lo encontraríamos en el Imperio de los Incas. “Según Molina el cuzqueño, al lado de la exposición de hechos memorables a base de quipus, manejados por expertos quipucamayos que tenían un específico lugar de preparación profesional, existió una especie de museo pictórico, casa que llama Pokencancha, donde estaba escrito mediante kilca «la vida de cada uno de los Incas y de las tierras que conquistó, pintado por sus figuras en unas tablas», con expresión de los orígenes del Tawantinsuyu, sus principales fábulas explicatorias y los hechos más importantes. Constituía el gran repositorio informativo imperial, el archivo por excelencia del pueblo incaico. Sarmiento cuenta que Pachacútec llamó a los «viejos historiadores de todas las provincias que sujetó» y a otros del reino, los mantuvo en el Cuzco y examinó acerca de la antigua historia. Y conocidos los sucesos más notables, «hízolo todo pintar por su orden en tablones grandes y deputó en las casas del sol una gran sala, adonde las tales tablas, que guarnecidas de oro estaban, estuviesen como nuestras librerías y constituyó doctores que supiesen entenderlas y declararlas. -

Historia Universidad De San Marcos De Lima

CUBIERTA HISTORIA DE LA UNIVERSIDAD Lomo 8 mm.qxp_Maquetación 1 26/08/20 17:36 Página 1 LIMA DE Fray Antonio de la Calancha, OSA SAN MARCOS HISTORIA DE DE LA Francisco Javier Campos Gloria Cristina Flórez es Doctora y Fernández de Sevilla, OSA UNIVERSIDAD en Historia por la Pontificia Univer sidad Católica del Perú. Post grado www.javiercampos.com en Historia de América en la Uni UNIVERSIDAD UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN MARCOS versidad Complutense de Madrid. – Natural de Villanueva de los In Especialista en Civilización Medie fantes (Campo de Montiel, tierra DE LA val por la Universidad Católica de de La Mancha). DE LIMA Lovaina. Es Docente Extraordinario – Realiza estudios eclesiásticos en Experto y Responsable de la Cáte Salamanca y en el Real Monas dra Ella Dunbar Temple en la Uni terio del Escorial. versidad Nacional Mayor de San HISTORIA HISTORIA Marcos. Actualmente es Coordina – Licenciado en Filosofía y Letras, dora Académica del Diplomado Doctor en Historia. Virtual en Historia Universal en la – Fundador y Director del Instituto Universidad de Piura (sede Lima). Escurialense de Investigaciones TRANSCRIPCIÓN Ha sido miembro del Consejo de Históricas y Artísticas. Dra. Gloria Cristina Flórez Gobierno de la Universidad de NNUU con sede en Tokio. Ha publi – Doctor Honoris Causa en “Letras cado el libro Derechos Humanos y Humanas” por la Universidad INTRODUCCIÓN Medioevo: Un hitp en la evolución Católica de Miami, y de la Uni de una idea. versidad Nacional Mayor de San Dr. F. Javier Campos, OSA Marcos de Lima. – Miembro de las Reales Acade mias de la Historia, de la de INSTITUTO ESCURIALENSE DE INVESTIGACIONES Ciencias Nobles Artes y Bellas HISTÓRICAS Y ARTÍSTICAS Letras de Córdoba, de la de Bellas Artes de Sta.