Relation of Kwashiorkor in Early Childhood and Intelligence at School Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwashiokorl. Description of Kwashiorkor Kwashiorkor Is a Life-Threatening and Debilitating Form of Malnutrition. It's Caused B

Name ;OLAWUYI MUQTADIR OREDOLAPO COUSE AFE 101 DEPARTMENT ;ACCOUNTING KWASHIOKORl. Description of kwashiorkor kwashiorkor is a life-threatening and debilitating form of malnutrition. It’s caused by a lack of protein in your diet. Kwashiorkor is also commonly seen in low- and lower-middle-income regions facing famine. Signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor The symptoms of kwashiorkor include; • damaged immune system, which can lead to more frequent and severe infections • irritability. • flaky rash • shock. • change in skin and hair colour (to a rust colour) and texture • fatigue • diarrhea • loss of muscle mass • failure to grow or gain weight • edema (swelling) of the ankles, feet, and belly SUSCEPTIBLES If kwashiorkor is suspected, your doctor will first examine you to check for an enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) and swelling. Next, blood and urine tests may be ordered to measure the level of protein and sugar in your blood. Other tests may be performed on your blood and urine to measure signs of malnutrition and lack of protein. These tests may look for muscle breakdown and assess kidney function, overall health, and growth. These tests include: arterial blood gas, blood urea nitrogen , urinalysis e.t.c. TREATMENT Kwashiorkor can be corrected by eating more protein and more calories overall, especially if treatment is started early. You may first be given more calories in the form of carbohydrates, sugars, and fats. Once these calories provide energy, you will be given foods with proteins. Foods must be introduced and calories should be increased slowly because you have been without proper nutrition for a long period. Your body may need to adjust to the increased intake. -

Involvement of the Eye in Protein Malnutrition * -303

Bull. Org. mond. Sante 1958, 19, 303-314 Bull. Wld Hith Org. INVOLVEMENT OF THE EYE IN PROTEIN MALNUTRITION * D. S. McLAREN, M.D., Ph.D., D.T.M. & H. Medical Research Officer, East African Institute for Medical Research, Mwanza, Tanganyika Formerly at the MRC Human Nutrition Research Unit, National Institute for Medical Research, London SYNOPSIS An extensive review of the literature on protein malnutrition, with special reference to the frequency of involvement of the eyes, has been made by the author. Consideration of accounts from all parts of the world and in many different languages, including early as well as more recent descriptions of the syndrome, indicates that this important complication has not received sufficient attention hitherto. The evidence available suggests that it is nearly always an accompanying deficiency of vitamin A that is responsible. Less commonly reported-and producing less severe effects-is deficiency of the B-complex vitamins, and there is no clear evidence to date that protein deficiency itself damages the eyes in these cases. The ways in which protein lack might interfere with various aspects of vitamin-A metabolism are discussed, but it is pointed out that their actual significance in human disease is not yet known. A low dietary intake of vitamin A is regarded by the author as being the prime factor in the causation of eye complications, and attention is drawn to the necessity to correct this as part of any prophylactic or therapeutic programme aimed primarily at combat- ing protein malnutrition. The syndrome known by such various names as kwashiorkor, nutritional oedema syndrome, sindrome pluricarencial, and many others (Trowell, Davies & Dean, 1954), and characterized chiefly by a dietary deficiency ofprotein, has been reported as occurring amongst most of the malnourished communities of the world. -

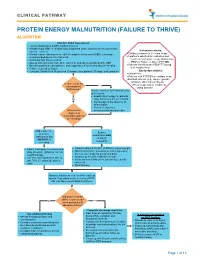

Protein Energy Malnutrition (Failure to Thrive) Algorithm

CLINICAL PATHWAY PROTEIN ENERGY MALNUTRITION (FAILURE TO THRIVE) ALGORITHM Conduct Initial Assessment • History and physical (H&P), nutrition focused • Weight height, BMI, % of ideal body weight and exam: assess severity (symmetric edema = severe) Inclusion criteria: • • Consider basic labs based on H&P; A complete blood count (CBC) is strongly Children newborn to 21 years of age • recommended due to risk of anemia Inpatients admitted for evaluation and • Additional labs based on H&P treatment of Protein Energy Malnutrition • Assess micronutrients: iron, zinc, vitamin D, and others as indicated by H&P (PEM) or Failure to thrive (FTT) OR • • Baseline potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium if concerned about re-feeding Patients identified with PEM/FTT during • Calorie count up to 3 days their hospital stay. • Consults: Social Work, Registered Dietician, Occupational Therapy, and Lactation Exclusion criteria: • Outpatients • Patients with FTT/PEM secondary to an identified concern (e.g., cancer, genetic condition, other chronic illness). Is there a risk for •Pts w/ suspected or confirmed micronutrient Yes eating disorder deficiencies? Initiate treatment for micronutrients deficiencies: • Empiric zinc therapy for patients No older than 6 months for 1 month • Iron therapy in the absence of inflammation • Vitamin D and other What are the micronutrients based on labs degrees of malnutrition and risk of refeeding? Mild, moderate, Severe or severe malnutrition AND malnutrition but at risk of NO RISK of refeeding refeeding • • Initiate feeding per recommended Initiate feeding at 30-50% of RDA for current weight • daily allowance (RDA) for current Monitor potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium weight and age once to twice a day for a total of 4 days • • Use PO route if patient is able to Advance by 10-20% if labs are normal • take 70% of estimated calories If labs abnormal hold off on advancing feed until orally corrected • Start thiamine Advance calories to meet level for catch up growth. -

Nutritional Dermatoses in the Hospitalized Patient

HOSPITAL CONSULT IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE SOCIETY FOR DERMATOLOGY HOSPITALISTS Nutritional Dermatoses in the Hospitalized Patient Melissa Hoffman, MS; Robert G. Micheletti, MD; Bridget E. Shields, MD Nutritional deficiencies may arise from inadequate nutrient intake, abnormal nutrient absorption, or improper nutrient PRACTICE POINTS utilization.4 Unfortunately, no standardized algorithm for • Nutritional deficiencies are common in hospitalized screening and diagnosing patients with malnutrition exists, patients and often go unrecognized. making early physical examination findings of utmost • Awareness of the risk factors predisposing patients importance. Herein, we present a review of acquired nutri- to nutritional deficiencies and the cutaneous manifes- tional deficiency dermatoses in the inpatient setting. tations associated with undernutrition can promote copy early diagnosis. Protein-Energy Malnutrition • When investigating cutaneous findings, undernutri- tion should be considered in patients with chronic Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) refers to a set of infections, malabsorptive states, psychiatric illness, related disorders that include marasmus, kwashiorkor and strict dietary practices, as well as in those using (KW), and marasmic KW. These conditions frequently are certain medications. seen in developing countries but also have been reported 5 • Prompt nutritional supplementation can prevent patient in developed nations. Marasmus occurs from a chronic morbidity and mortality and reverse skin disease. deficiencynot of protein and calories. Decreased insulin pro- duction and unopposed catabolism result in sarcopenia and loss of bone and subcutaneous fat.6 Affected patients include children who are less than 60% ideal body weight Cutaneous disease may be the first manifestation of an underlying nutri- 7 tional deficiency, highlighting the importance of early recognition by der- (IBW) without edema or hypoproteinemia. -

A Case of Kwashiorkor Presenting with Pericardial Effusion

orts & Ca Taheri et al., Med Rep Case Stud 2017, 2:2 ep se R S l t a u DOI: 10.4172/2572-5130.1000134 c d i i d e s e M + Medical Reports & Case Studies ISSN: 2572-5130 CaseResearch Report Article Open Access A Case of Kwashiorkor Presenting with Pericardial Effusion Taheri S*, Surak A, Bravo G, McMurray A and Altamirano-Diaz L Department of Paediatrics, Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre, Western University, London, UK Abstract Introduction: Kwashiorkor is a type of protein-calorie malnutrition often seen in children of impoverished countries and famine. It is a result of insufficient protein intake in the context of adequate caloric intake. Case report: We report a case of a 13-year-old male with trisomy 21 in Southwestern Ontario, Canada who presented with bilateral pneumonia, pericardial effusion and peripheral edema. Evaluation revealed severe dietary restriction, consistent with kwashiorkor. Child was placed on severely restrictive diet, particularly limiting dairy intake to one daily cup of plain, unfortified yogurt. His hospital course was complicated with severe hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia and hypophosphatemia. These findings resolved gradually upon slow introduction of well-balanced diet and adequate caloric and protein intake. Conclusion: Malnutrition is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed in developed countries with devastating outcomes if unrecognized. This makes it imperative to consider this diagnosis, recognize potential risk factors and be prepared to accurately assess overall nutritional status. Keywords: Malnutrition; Kwashiorkor; Case report; pneumonia; in Canada. He is the first child born to parents of East Indian descent Respiratory; Pericardial effusion (unknown exact geographic region). -

Serum and Red Cell Folates, and Serum Vitamin B12 in Protein Calorie Malnutrition

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.48.5.366 on 1 May 1973. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1973, 48, 366. Serum and red cell folates, and serum vitamin B12 in protein calorie malnutrition M. KHALIL, A. TANIOS, M. MOGHAZY, M. K. AREF, S. MAHMOUD, and M. EL LOZY From the Departments of Paediatrics, Clinical Pathology, and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt Khalil, M., Tanios, A., Moghazy, M., Aref, M. K., Mahmoud, S., and el Lozy, M. (1973). Archives of Disease in Childhood, 48, 366. Serum and red cell folates, and serum vitamin B12 in protein calorie malnutrition. In 22 cases of kwashiorkor, 19 cases of marasmus, and 16 normal controls, red cell folate, serum folate, and serum vitamin B1, were estimated, and the bone marrow and peripheral blood examined. Erythrocyte folate deficiency was shown in 9 cases of kwashiorkor and 7 cases of marasmus. Serum folate deficiency was present in 14 cases of kwashi- orkor and 7 cases of marasmus. Megaloblastosis was found in 45% of cases of kwashiorkor and 37% of cases of marasmus. Megaloblastosis and macrocytosis correlated more with erythrocyte than with serum folate deficiency. Serum vitamin B1, levels in children with kwashiorkor or marasmus did not differ from those of normal controls. The role of folate deficiency in the pathogenesis of megaloblastosis in protein calorie malnutrition was confirmed. copyright. A hypochromic anaemia of iron deficiency is a Material and methods salient finding in patients with protein calorie The study was carried out on 22 infants (12 males and malnutrition (Khalil, Awwad, and Hafez, 1968). -

A Child with Kwashiorkor Misdiagnosed As Atopic Dermatitis

Volume 23 Number 5 | May 2017 Dermatology Online Journal || Letter DOJ 23 (5): 17 A child with kwashiorkor misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis Marcus Henrique de S B Xavier MD, MsC, Eduardo de Magalhães MD, Gilmar Ferraz Oliveira MD, Mariana Keltke Magalhães MD, Cláudio Prates de Almeida e Oliveira MD, Natália Bragança Oliveira MD Affiliations: Hospital Infantil Padre Anchieta, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil Corresponding Author: Marcus H. Xavier,MD, MSC, 465 Mangabeira street, Suite 601, Belo Horizonte, MG 30350-170, Brazil, Email: marcus_ [email protected] Abstract The condition is a type of protein-calorie malnutrition most often seen in children of impoverished countries Although uncommon, kwashiorkor continues to occur or areas of famine. Causes are controversial, but the in developed, but mainly in developing nations. It is a most commonly accepted theory is inadequate type of protein-calorie malnutrition that occurs in the dietary protein in the presence of sufficient caloric setting of insufficient protein intake in the presence of intake [1-4]. Children placed on restrictive diets by sufficient caloric intake. Skin and hair changes should ‘‘well-intending’’ parents, as a result of concern for prompt a thorough dietary history and appropriate food allergies, have been reported to be previously dietary intervention. We report a case of a 12-month- at risk of nutritional deficiency, such as kwashiorkor old girl in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, who [3, 4]. presented with diffuse edema, desquamation, and irritability misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis. The Case Synopsis diagnosis was consistent with kwashiorkor as a result A 12-month-old girl presented with a 3-month of severe dietary restriction. -

Kwashiorkor in Africa * J

Bull. Org. mond. Sante 1952, 5, 1-71 Bull. World Hlth Org. KWASHIORKOR IN AFRICA * J. F. BROCK, D.M., F.R.C.P. Professor of the Practice of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Union of South Africa Consultant in Nutrition, World Health Organization M. AUTRET, Dr Pharm. Chief, Area and Field Branch, Nutrition Division, Food and Agriculture Organization Manuscript received in July 1951 Page Introduction ...... .. .. .. .. 2 1. Medical aspects of kwashiorkor ..... 5 1.1 Definition, and description of individual clinical characters .5... S 1.2 General clinical picture ..... 24 1.3 Nutritional cirrhosis and primary carcinoma of the liver .... 25 1.4 Frequency of the syndrome ..... 27 1.5 Treatment ....... .. .. .. .. .. 28 2. Kwashiorkor and diet ..... 29 2.1 Food consumption and feeding practices ... 29 2.2 Relation between kwashiorkor and diet .... 39 3. Etiology of kwashiorkor ..... 47 4. Prevention of kwashiorkor ..... 51 4.1 Increasing the supply of proteins ..... 51 4.2 The hungry months ...... 56 4.3 Supplementary feeding of infants and young children .... 57 4.4 Education ....... .. .. .. .. .. 59 4.5 Immediate action ...... .. 60 Recommendations ...... .. 60 Summary Resume|62 . Annex 1. Recent and current clinical and biochemical studies in Africa 65 References ....... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 69 * This paper will also be published, in English and in French, in the Monograph Series of the World Health Organization. it was published in Spanish by the Food and Agriculture Organizatian of the United Nations, in September 1951, as FAQ - Estudios de Nutricidn, No. 8. - ED. 102 - 1 - 2 J. F. BROCK & M. AUTRET INTRODUCTION This report is the result of a recommendation made by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition at its first session in Geneva in October 1949. -

PELLAGRA and Its Prevention and Control in Major Emergencies ©World Health Organization, 2000

WHO/NHD/00.10 Original: English Distr.: General PELLAGRA and its prevention and control in major emergencies ©World Health Organization, 2000 This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. Acknowledgements The Department of Nutrition for Health and Development wishes to thank the many people who generously gave of their time to comment on an earlier draft version of this document. Thanks are due in particular to Rita Bhatia (United Nations High Commission for Refugees), Andy Seal (Centre for International Child Health, Institute of Child Health, London), and Ken Bailey, formerly of the Department of Nutrition for Health and Development; their suggestions are reflected herein. In addition, Michael Golden (University of Aberdeen, Scotland) provided inputs with regard to the Angola case study; Jeremy Shoham (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) completed and updated the draft version and helped to ensure the review’s completeness and technical accuracy; and Anne Bailey and Ross Hempstead worked tirelessly to prepare the document for publication. This review was prepared by Zita Weise Prinzo, Technical Officer, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development. i Contents -

The Concept of Kwashiorkor from a Public Health Point of View

458 NOTES climatologically different areas, and reared under standard conditions to eliminate the environmental causes of chromosomic rearrangements-inter alia, temperature, food, salinity. It would, of course, be most desirable to deal with strains as pure as possible. Crossing experiments would then more probably give valid information on the racial differentiations and the amount of geographical isolation within the species. The subsequent inducing of resistance into one of these strains, followed by a study of the possible chromosomic rearrangements and of the fate of hybrids, would be yet another step forward. Finally, the introduction of naturally resistant strains, the study of their chromosomic pattern and the carrying out of crossing experiments with other strains maintained in the laboratory would usefully complete the research programme. This would be a very long and ambitious task, but I feel that it would be of considerable help in solving some of the problems which are a very real source of annoyance to many malariologists in charge of control projects. The Concept of Kwashiorkor from a Public Health Point of View by J. C. WATERLOW, M.D., Tropical Metabolism Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Jamaica, and NEVIN S. SCRIMSHAW, Ph.D., M.D., Instituto de Nutrici6n de Centro America y Panamd (INCAP), Guatemala It is now generally agreed that the type of severe malnutrition in infants and young children for which the name kwashiorkor is widely used is basically the same in many parts of the world-in Africa, India, and South- East Asia, the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, and Europe. Underlying many differences in terminology and regional variations in the details of the clinical picture, there is a fundamental unity. -

Malnutrition Disease

BASIC Freedom from Hunger Campaign STUDY MALNUTRITION AND DISEASE It_., WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION· GENEVA· SWITZERLAND FREEDOM FROM HUNGER CAMPAIGN Basic Studies Series A series of Basic Studies supporting the Freedom from Hunger Campaign is being published by the Food and Agriculture Organization and other organizations of the United Nations. Sixteen such studies are contemplated in the series; nine will be issued by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) , three by the United Nations, and one each by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the International Labour Organisation (ILO) , the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Meteoro- logical Organization (WMO). ' The subjects cover a wide range and include, for example, the possi bilities of increasing world food production, the part marketing can play in increasing productivity, education and training in nutrition, animal diseases and human health, economic development through food, popula tion and food supplies, education in relation to agriculture and economic development, hunger and social policy, malnutrition and disease, weather and food. This volume, Malnutrition and disease, issued by the World Health Organization, is No. 12 in the series. The following titles have already been issued: No.1. Weather and food, WMO, Geneva. No.2. Development through food-A strategy for surplus utilization, FAO, Rome. No.3. Animal disease and human health, FAO, Rome. No.4. Marketing-Its role in increasing productivity, FAO, Rome. No.5. Nutrition and working effiCiency, FAO, Rome. No.6. Education and training in nutrition, FAO, Rome. No.7. Population and food supply, United Nations, New York. No.8. Aspects of economic development-The background to freedom from hunger, United Nations, New York. -

The Long-Term Effects of Early Kwashiorkor Compared with Marasmus. IV. Performance on the National High School Entrance Examination

003 1-3998/90/2803-0235$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 28, No. 3, 1990 Copyright O 1990 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in (I.S. A The Long-Term Effects of Early Kwashiorkor Compared with Marasmus. IV. Performance on the National High School Entrance Examination JANINA R. CALLER, FRANK C. RAMSEY, DEBRA S. MORLEY, ESTHER ARCHER, AND PATRICIA SALT Center f6r Behavioral Developmmt and Mental Retardation, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mussach~lsetts021 18 and Department of Pediatrics, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Bridgetown, Barbados ABSTRACT. This is one of a series of studies on the long- However, the previously malnourished children had continuing term effects of early childhood malnutrition in Barbadian deficits in cognitive and behavioral functioning through the school children. This is the first report of the relationship school years, which included impaired IQ performance (2) and between early malnutrition and later performance on a attention deficits reported by teachers and parents (4). Socioeco- national examination administered to all 11-y-old children nomic and home environmental factors during childhood and in Barbados to assign high school seats. We compared adolescence did not play a major role in these findings. scores achieved on the 11-plus examination by 103 boys The opportunity presented itself to use the results of the 1 I- and girls with histories of marasmus or kwashiorkor with plus examination administered to all I 1-y-old children in Bar- those obtained by 63 healthy comparison children and also bados. Scores achieved on this national examination were used with scores obtained by the total island population of by the Barbadian Ministry of Education to rank children for children during the same years.