David Stone on Enemy at the Gates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friendly Fire Project Examines How a Country Views Itself by How It Tells Its War Story, We Are Also Very Interested in What Other Countries Consume for Entertainment

00:00:00 Music Music Soft, melancholy, somewhat eerie music. 00:00:01 Adam Host If it feels like there are a lot of films about Stalingrad, you’re not Pranica wrong. A quick search in your movie streaming service of choice—or if you’re so lucky, a brick-and-mortar video store—will reveal ten of them. Although only one, to our knowledge, has a scene depicting a Rachel Weisz hand job. It’s enough film content to spin off a podcast of its own, and I’ve already pitched Earwolf a show about German/Russian World War II films with an emphasis on fighter plane aerodynamics/equestrian cavalry enclosures hosted by fifth-year college seniors from acting school with limb fractures called The Stalingrad Stall Stall Stallin’ Grad Cast Cast Cast. For comparison, there are only five more films made about Pearl Harbor, and that’s if you don’t disqualify the Michael Bay movie, which we do. This Stalingrad film is the most successful Russian film of all time, earning 51 million domestically in Russia and $68 million globally. And while the Friendly Fire project examines how a country views itself by how it tells its war story, we are also very interested in what other countries consume for entertainment. Stalingrad accomplishes both. But does that say anything about the importance of this battle in the story of World War II, and the historical record? Well, in our experience watching war films, sometimes quantity doesn’t equal quality. And this is a film that tries very hard to project quality. -

Enemy at the Gates

IS IT TRUE? 0. IS IT TRUE? - Story Preface 1. STALINGRAD 2. SOVIET RESISTANCE 3. THE SIEGE OF STALINGRAD 4. VASILY ZAITSEV 5. TANIA CHERNOVA 6. STALINGRAD SNIPERS 7. THE DUEL 8. IS IT TRUE? 9. OPERATION URANUS 10. HITLER FORBIDS SURRENDER 11. GERMAN SURRENDER 12. THE SWORD OF STALINGRAD Most scholars recognize Antony Beevor’s 1998 book, Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, as the best account of the battle. Beevor interviewed survivors and uncovered extraordinary documents in both German and Russian archives. His monumental work discusses Vasily Zaitsev and his talents as a sniper. But of the duel story, Beevor reports, at page 204: Some Soviet sources claim that the Germans brought in the chief of their sniper school to hunt down Zaitsev, but that Zaitsev outwitted him. Zaitsev, after a hunt of several days, apparently spotted his hide under a sheet of corrugated iron, and shot him dead. The telescopic sight off his prey’s rifle, allegedly Zaitsev’s most treasured trophy, is still exhibited in the Moscow armed forces museum, but this dramatic story remains essentially unconvincing. If the telescopic sight is still on display, and the story made all the papers, why does Beevor think it is not convincing? It is worth noting that there is absolutely no mention of it[the duel] in any of the reports to Shcherbakov [chief of the Red Army political department], even though almost every aspect of ‘sniperism’ was reported with relish. What did Vasily Zaitsev have to say about the duel? Living to old age in the Ukraine, where he was the director of an engineering school in Kiev, this Hero of the Soviet Union was apparently quoted by Alan Clark in Barbarossa: The sun rose. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries WAR The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 Anthropoid DVD-8859 1776 DVD-0397 Apocalypse Now DVD-3440 1900 DVD-4443 DVD-6825 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 Army of Shadows DVD-3022 9th Company DVD-1383 Ashes and Diamonds DVD-3642 Act of Killing DVD-4434 Auschwitz Death Camp DVD-8792 Adams Chronicles DVD-3572 Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi State DVD-7615 Aftermath: The Remnants of War DVD-5233 Bad Voodoo's War DVD-1254 Against the Odds: Resistance in Nazi Concentration DVD-0592 Baghdad ER DVD-2538 Camps Age of Anxiety VHS-4359 Ballad of a Soldier DVD-1330 Al Qaeda Files DVD-5382 Band of Brothers (Discs 1-4) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alexander DVD-5380 Band of Brothers (Discs 5-6) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alive Day Memories: Home from Iraq DVD-6536 Bataan/Back to Bataan DVD-1645 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD-0238 Battle of Algiers DVD-0826 DVD-1284 Battle of Algiers c.4 DVD-0826 c.4 America Goes to War: World War II DVD-8059 Battle of Algiers c.3 DVD-0826 c.3 American Humanitarian Effort: Out-Takes from Vietnam DVD-8130 Battleground DVD-9109 American Sniper DVD-8997 Bedford Incident DVD-6742 DVD-8328 Beirut Diaries and 33 Days DVD-5080 Americanization of Emily DVD-1501 Beowulf DVD-3570 Andre's Lives VHS-4725 Best Years of Our Lives DVD-5227 Anne Frank DVD-3303 Best Years of Our Lives c.3 DVD-5227 c.3 Anne Frank: The Life of a Young Girl DVD-3579 Beyond Treason: What You Don't Know About Your DVD-4903 Government Could Kill You 9/6/2018 Big Red One DVD-2680 Catch-22 DVD-3479 DVD-9115 Cell Next Door DVD-4578 Birth of a Nation DVD-0060 Charge of the Light Brigade (Flynn) DVD-2931 Birth of a Nation and the Civil War Films of D.W. -

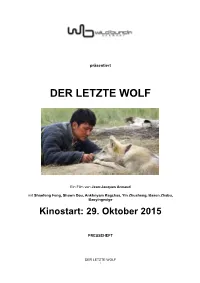

Der Letzte Wolf

präsentiert DER LETZTE WOLF Ein Film von Jean-Jacques Annaud mit Shaofeng Feng, Shawn Dou, Ankhnyam Ragchaa, Yin Zhusheng, Basen Zhabu, Baoyingexige Kinostart: 29. Oktober 2015 PRESSEHEFT DER LETZTE WOLF 1 VERLEIH Wild Bunch Germany GmbH Holzstraße 30 80469 München PRESSEBETREUUNG mm filmpresse Schliemannstraße 5 10437 Berlin Tel. 030 – 41 71 57 23 Fax: 030 – 41 71 57 25 [email protected] MATERIAL / INFORMATIONEN Über die Homepage www.wildbunch-germany.de haben Sie die Möglichkeit, sich für die Presse-Lounge zu akkreditieren. Dort stehen Ihnen alle Pressematerialien, Fotos und viele weitere Informationen als Download zur Verfügung: www.wildbunch-germany.de/press. Ihre Zugangsdaten sind dieselben wie bei Senator Film Verleih. DER LETZTE WOLF 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS BESETZUNG & STAB 04 TECHNISCHE DATEN 04 KURZINHALT & PRESSENOTIZ 05 LANGINHALT 06 INTERVIEW MIT JEAN-JACQUES ANNAUD 08 BIOGRAFIE JEAN-JACQUES ANNAUD 12 JIANG RONG – ROMANAUTOR 14 SHAOFENG FENG – CHEN ZHEN 15 SHAWN DOU – YANG KE 15 ANDREW SIMPSON – TIERTRAINER 16 JAMES HORNER – MUSIK 18 MENSCH UND TIER – EIN INTERVIEW MIT BORIS CYRULNIK 19 GESCHICHTE DER WÖLFE 22 KULTURREVOLUTION IN CHINA 27 DIE INNERE MONGOLEI 29 DER LETZTE WOLF 3 BESETZUNG Shaofeng Feng Chen Zhen Shawn Dou Yang Ke Ankhnyam Ragchaa Gasma Yin Zhusheng Bao Basen Zhabu Shunghi Baoyingexige Bilig STAB Regie Jean-Jacques Annaud Drehbuch Alain Godard Jean-Jacques Annaud Lu Wei John Collee Nach dem Roman „Der Zorn der Wölfe“ von Jiang Rong Musik James Horner Tiertrainer Andrew Simpson Kamera Jean Marie Dreujou, AFC Schnitt Reynald Bertrand Regieassistenz Matthieu de la Mortière, AFAR Xi Zi Szenenbild Quan Rongzhe Mischung Cyril Holtz Visuelle Effekte Christian Rajaud Guo Jianquan Eine chinesisch-französische Koproduktion China Film Co., LTD. -

History 133 the Russian Revolutions from Lenin to Putin Matthew Lenoe Rush Rhees Library 372 [email protected]

History 133 The Russian Revolutions from Lenin to Putin Matthew Lenoe Rush Rhees Library 372 [email protected] Course Overview: Russia’s history over the past century has been extraordinarily turbulent. Russians have experienced war and revolution, state terror, anarchy, famine, mass epidemics, industrialization, and dizzying social, political and economic transformations. In this course we will focus on four eras of rapid change – the Russian revolution of 1917-1921, the “revolution from above” of 1928-1938 which combined breakneck industrialization, forced collectivization of agriculture and terror, the years of de-Stalinization and liberalization under Nikita Khrushchev (1956-1964), and finally the collapse of the USSR and the rise of a new authoritarianism personified by Vladimir Putin. We will ask which of these phenomena deserves the title of “revolution,” and we will explore the deeper causes of change as well as the experiences of ordinary Russians in this tumultuous century. The goals of this course include – Learning close analysis of documents and debates within their historical contexts. Moving beyond stereotypes about “the Russian bear,” and Russians’ supposed longing for “the iron fist” to a more nuanced understanding of the processes and driving forces of modern Russian history. Understanding the deep background of present-day developments in Russia (for example, growing authoritarian nationalism and the takeover of Crimea). Gaining a basic knowledge of the most important events, prominent personalities, socioeconomic developments, etc. in Russian history from 1900 to the present. Improving students’ skills in writing and argument. Examine the meanings of the word “revolution” and learn the concept of “heuristic device” and the importance of defining terms in an argument. -

Not a Step Back by Leanne Crain

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2016 Vol. 14 The beginning of the war in Russia came as a Not a Step Back surprise to the Soviet government, even though they Leanne Crain had been repeatedly warned by other countries that History 435 Nazi Germany was planning an attack on Russia, and nearly the entire first year of the German advance into Russia was met with disorganization and reactionary planning. Hitler, and indeed, most of the top military minds in Germany, had every right to feel confident in their troops. The Germans had swept across Europe, not meeting a single failure aside from the stubborn refusal of the British to cease any hostilities, and they had seen how the Soviets had failed spectacularly in their rushed invasion of Finland in the winter of 1939. The Germans had the utmost faith in their army and the success of their blitzkrieg strategy against their enemies further bolstered that faith as the Germans moved inexorably through the Ukraine and into Russian territory nearly uncontested. The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact had kept Germany safe from any attack from Russia, “Such talk [of retreat] is lying and harmful, it weakens but Hitler had already planned for the eventuality of us and strengthens the enemy, because if there is no end invading Russia with Operation Barbarossa. Hitler was to the retreat, we will be left with no bread, no fuel, no convinced that the communist regime was on the verge metals, no raw materials, no enterprises, no factories, of collapse, and that the oppressed people under Stalin and no railways. -

The Battle of Stalingrad

74 X Stalingrad: y t u LL. o z The Battlefield of History ... o The History of a Battlefield Stalingrad: ••HO The Fateful Siege 1942-1943 by Antony Beevor Penguin, London, 1998 Enemy at the Gates A Film directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud 2001 -'-v~-y The Battle of Stalingrad, a titanic ,t collision in the Second World War be• ..v tween Nazi Germany and the then so• cialist Soviet Union, has been the sub• ject of countless studies, books, films and .memoirs. However, two recent works, one a history by Antony Beevor, one of Britain's most impor- . tant writers on military affairs, the other a major film from the French director Jean-Jacques Annaud, have helped acquaint a new generation with what is widely held to be the greatest battle in history. Not only was it a military clash on a giant scale, pitting millions of soldiers against each other, it was even more the key act in an unfolding drama in which two social systems - the capitaKst-imperialist system in the form of German Nazis, and the system \ that had been born of the October Revolution and built up in two dec- • ades of socialist construction under the "^1 leadership of Lenin and Stalin - con• fronted each other in life-or-death com• • ; / bat. It was the turning point in the Sec• ond World War and the beginning of the end of Hitler's Germany, which, «»2 Left: Red Army soldiers in the ifl«ltt«j§ "Stalingrad Academy of Street- fighting". Right: Red Army Divisional Commander at the front with his troops. -

Changing Attitudes Toward War and Women in Twentieth Century Film

Changing Attitudes Toward War and Women in Twentieth Century Film Mary Ann T. Natunewicz INTRODUCTION This unit has been written for use in two eleventh grade United States History courses. One course covers the period from 1865 to the present, while the second course, an Advanced Placement program, begins at the period of colonization. This unit will be used over a semester in sections that deal with World Wars I and II, the Korean Conflict, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War. Most of the curriculum here could also be adapted for ninth grade courses. Each section of the lesson plans is designed for one or two 45- minute periods. The school in which this will be taught is an urban high school with 2500 students, a significant number of whom are refugees who have had first hand experience with war. Students who are still learning English will find films that use dialects and non-standard English especially challenging. PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF UNIT It is the purpose of this unit to show students that war films do more than tell stories and provide catharses for viewers. Each film also conveys the social values and the mores of the period in which it was produced and addresses attitudes not only toward war, but also toward topics closely associated with war, such as the morality of fighting, the causes for which it is moral and just to fight, the definition of heroism and the responsibility of the individual to exhibit ethical behavior. Frequently, the causes worth fighting for are such things as political systems, home and family. -

Rattenkrieg: Infantry Aces Stalingrad

Rattenkrieg: Infantry Aces Stalingrad 1 Introduction: The recent release of Casino from Battle Front's Flames of War has got me thinking a lot about my favorite battle in all of WW2. STALINGRAD. I love this battle. I have watch Enemy at the Gates a hundred times, I have read Anthony Beavers book Stalingrad a hundred times, have printed every wiki article on the battle for light work reading and spent endless nights on end staring at the maps in Osprey books while my wife tried to sleep. At one point I put on a Stalingad campaign using the Blitzkreig Commander II Rules, which can be found in the AARs section of my blog. In fact Stalingrad got my blog started. We fought our way through the city and into the German counter offensive until it puttered out as all Campaigns do. I built a ton of terrain for the series of games including a grain silo and the G.U.M. Department store from scratch. We had epic house to house and block to block fights using BKC II. A new Stalingrad campaign will give me a reason to use the buildings again and replay my WW2 passion: STALINGRAD! Any way after getting my recent copy of Wargames Illustrated and reading the infantry aces sneak peeks and mini campaign sneak peak, I started to get the Stalingrad itch again. I also recently bought a Mosin Nagant which doesn't help either. For anyone who reads the FoW forums regularly, or sees any of my WW2 comments on other forums and blogs knows I have thought for a long time that Battle Front should have more Midwar briefings, specifically a Stalingrad briefing. -

Fighting in the Streets

Fighting in the Streets Testing Theory on Urban Warfighting Keywords: Urban Warfare, Alice Hills, Stalingrad, Grozny, Mogadishu. Viktor Villner Supervisor: Alastair Finley Swedish Defense University International Master’s Programme in Politics and War Viktor Villner Swedish Defense University Master’s Thesis 2017-05-24 Abstract This paper sets out to examine why it is that combat in urban environments is so deadly and casualty-heavy for conventional militaries, even when those militaries hold a technological and/or numerical advantage. The paper aims to test the theory of Alice Hills through a structured, focused comparison on three cases of urban warfighting. The paper examines the battle of Stalingrad 1942-1943, the battle of Mogadishu 1993 and the first battle of Grozny in 1994. Support for Hills theory is found in what she argues is a pre-modern type of combat that is slow- going and relies upon ground forces as well as the equalization of technological advantages through improvised adaptation of older and/or less than ideal equipment. The paper highlights the need for intelligence in urban operations, especially human intelligence, as a potentional further development of Hills theory. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Previous Research .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Urban Operations.......................................................................................................................................................... -

How Did the Red Army of the Soviet Union So Fiercely and Victoriously

The Story behind the Battle: How did the Red Army of the Soviet Union so fiercely and victoriously defend Stalingrad in 1942-43 despite the lack of trained officers, equipment, preparation, and morale in 1941? Carol Ann Taylor Student No. 30620882 Thesis for Honours Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History School of Social Sciences and Humanities Murdoch University 2012 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bachelor of Arts in History with Honours at Murdoch University, 2 November 2012 I declare that this thesis is a true account of my own work, unless indicated Signed: Carol Ann Taylor Date: 2 November 2012 Copyright Acknowledgement Form I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions s51.2 of the Copyright Act 1968, all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such a reproduction is for the purpose of study, and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: ................................................................................................ Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Arts with Honours in History Thesis Title: The Story behind the Battle: How did the Red Army of the Soviet Union so fiercely and victoriously defend Stalingrad in 1942-43 despite the lack of trained officers, equipment, preparation, and morale in 1941? Author: Carol Ann Taylor Year: 2002 Abstract The victory over Axis forces by the Red Army during the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942-1943 is considered one of the major turning points of World War Two. -

World War Ii in Popular American Visual Culture: Film and Video Games After 9/11

WORLD WAR II IN POPULAR AMERICAN VISUAL CULTURE: FILM AND VIDEO GAMES AFTER 9/11 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Maria Cristina Ana Kabiling, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 22, 2010 WORLD WAR II IN POPULAR AMERICAN VISUAL CULTURE: FILM AND VIDEO GAMES AFTER 9/11 Maria Cristina Ana Kabiling, B.A. Mentor: Arnold J. Bradford, Ph.D. ABSTRACT From the opening of the World War II Memorial at the National Mall in 2003, to the recently Oscar-nominated movie, Inglourious Basterds in 2010, to the immensely popular video game series first introduced in 2003 called Call of Duty, it becomes apparent that the first decade of the 21st century has witnessed a visual resurrection of scenes and themes from the Second World War. In turn, the context of the post-9/11 world, otherwise known as the “war on terrorism,” changed the way representations of the Second World War are both created and perceived. This leads to the central question of this research—why is World War II an important subject in popular American visual culture after the events of 9/11? Consequentially, is the revival of World War II themes in recent popular American visual culture a venue to address problems of social values confronting American culture? This research answers that question through an analysis and evaluation of the different intellectual, political, and emotional responses garnered by American audiences from specific films namely, Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, Bryan Singer’s Valkyrie, and Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds.