“It's Almost Too Intense:” Nostalgia and Authenticity in Call of Duty 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM Award-Winning Lead Designer with international design development experience including: Design Direction, Design Management, Cross-Studio Collaboration, Mission Design, Scripting, Co-op and Multiplayer Ecosystems, Narrative and Combat Pacing, Chatter Writing, Cinematic Creation, Video Editing, Systems Tuning, Environmental Art, QuickTime Events, Spec Writing, Corporate & Industry Presentations, Film and Game Production Experience Ubisoft Reflections – Lead Level Designer Projects: Watch_Dogs, Tom Clancy’s The Division Time Line: June 2012 – Present Key Achievements: Lead team of 13 designers to deliver next-gen content on time and up to quality Developed implementation best practices for the design team Served as Interim Lead Game Designer Worked with Producers and Directors from co-development studios in Europe, Canada, and US Developed project schedule for design team Selected to represent Ubisoft in an international recruitment video Selected to represent Ubisoft Reflections at TIGA industry event Studio presentations in office and at external venues Video editing for studio presentation Volition Inc. – Design Director, Lead Mission Designer, and Designer 2 Projects: Saints Row: The Third, Saints Row: The Third DLC Packs, Unannounced Next-Gen Project Time Line: February 2010 – June 2012 Key Achievements: Directed three profitable projects to a delivery both on time and on budget Earned multiple awards and positive mentions in press for mission content Generated -

Call of Duty 1 Instruction Manual

call of duty 1 instruction manual File Name: call of duty 1 instruction manual.pdf Size: 1734 KB Type: PDF, ePub, eBook Category: Book Uploaded: 15 May 2019, 14:26 PM Rating: 4.6/5 from 830 votes. Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 12 Minutes ago! In order to read or download call of duty 1 instruction manual ebook, you need to create a FREE account. Download Now! eBook includes PDF, ePub and Kindle version ✔ Register a free 1 month Trial Account. ✔ Download as many books as you like (Personal use) ✔ Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. ✔ Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with call of duty 1 instruction manual . To get started finding call of duty 1 instruction manual , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Home | Contact | DMCA Book Descriptions: call of duty 1 instruction manual It is requested that this article, or a section of this article, needs to be expanded. Add to the discussion on what needs to be improved, or start your own discussion on the talk page. If you know of a command, but do not see it on the list, feel free to add it in the Commands section, but all coding must be verifiable.Click if you need to know anything about styling a page.Check it out! Check them out! The administrators are the arbitrators, mediators, janitors, and leaders of our wiki, having greater knowledge of wikitext, our policies, and are chosen for neutrality and maturity as well as contributions. -

Friendly Fire Project Examines How a Country Views Itself by How It Tells Its War Story, We Are Also Very Interested in What Other Countries Consume for Entertainment

00:00:00 Music Music Soft, melancholy, somewhat eerie music. 00:00:01 Adam Host If it feels like there are a lot of films about Stalingrad, you’re not Pranica wrong. A quick search in your movie streaming service of choice—or if you’re so lucky, a brick-and-mortar video store—will reveal ten of them. Although only one, to our knowledge, has a scene depicting a Rachel Weisz hand job. It’s enough film content to spin off a podcast of its own, and I’ve already pitched Earwolf a show about German/Russian World War II films with an emphasis on fighter plane aerodynamics/equestrian cavalry enclosures hosted by fifth-year college seniors from acting school with limb fractures called The Stalingrad Stall Stall Stallin’ Grad Cast Cast Cast. For comparison, there are only five more films made about Pearl Harbor, and that’s if you don’t disqualify the Michael Bay movie, which we do. This Stalingrad film is the most successful Russian film of all time, earning 51 million domestically in Russia and $68 million globally. And while the Friendly Fire project examines how a country views itself by how it tells its war story, we are also very interested in what other countries consume for entertainment. Stalingrad accomplishes both. But does that say anything about the importance of this battle in the story of World War II, and the historical record? Well, in our experience watching war films, sometimes quantity doesn’t equal quality. And this is a film that tries very hard to project quality. -

Introduction to the Warrior Ethos ■ 113

8420010_VE1_p110-119 8/15/08 12:03 PM Page 110 Section 1 INTRODUCTION TO Values and Ethics Track Values THE WARRIOR ETHOS Key Points 1 The Warrior Ethos Defined 2 The Soldier’s Creed 3 The Four Tenets of the Warrior Ethos e Every organization has an internal culture and ethos. A true Warrior Ethos must underpin the Army’s enduring traditions and values. It must drive a personal commitment to excellence and ethical mission accomplishment to make our Soldiers different from all others in the world. This ethos must be a fundamental characteristic of the U.S. Army as Soldiers imbued with an ethically grounded Warrior Ethos who clearly symbolize the Army’s unwavering commitment to the nation we serve. The Army has always embraced this ethos but the demands of Transformation will require a renewed effort to ensure all Soldiers truly understand and embody this Warrior Ethos. GEN Eric K. Shinseki 8420010_VE1_p110-119 8/15/08 12:03 PM Page 111 Introduction to the Warrior Ethos ■ 111 Introduction Every Soldier must know the Soldier’s Creed and live the Warrior Ethos. As a Cadet and future officer, you must embody high professional standards and reflect American values. The Warrior Ethos demands a commitment on the part of all Soldiers to stand prepared and confident to accomplish their assigned tasks and face all challenges, including enemy resistance—anytime, anywhere. This is not a simple or easy task. First, you must understand how the building blocks of the Warrior Ethos (see Figure 1.1) form a set of professional beliefs and attitudes that shape the American Soldier. -

INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd:2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite B

2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite a INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite b Table of Contents 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain 3 Your Soldiers 7 The Conflict 9 Reign of Terror 9 Geopolitical Intelligence Report: Zekistan 10 The HUD 12 Assessing the Environment 13 Commands Overview 15 Moving Your Soldiers 17 Fire Orders 19 Effects of Fire 20 Using Cover Against Threats 21 Grenades 23 Individual Fire Orders 23 Team Leader Tools 23 · Reporting with the Radio 24 · The Global Positioning System 25 · Saving your Progress 25 · Replays 25 · CASEVAC 26 · Profiles 26 · Mission Failure 27 Options 28 Co-operative Play 29 Online Menu 29 Online Options 31 Glossary 33 License Agreement 35 Register your Game! 35 Hints and Tips 35 Technical Support 36 Quickstart suomeksi 41 Quickstart på svenska 46 Credits 1 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain You command a dismounted light infantry squad, a highly trained group Rifleman (R) of soldiers who understand how to operate in a hostile, highly populated The Rifleman has the least experience of soldiers on the fireteam, but don’t environment. Everything about your squad – from its soldiers to its underestimate him – he’s had extensive training. The Rifleman fires rounds equipment to its tactics – is the result of careful planning and years of from his M class rifle where you direct him, and he also gives aid to experience on the battlefield. -

Copyright Undertaking

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk WAR AND WILL: A MULTISEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF METAL GEAR SOLID 4 CARMAN NG Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2017 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of English War and Will: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Metal Gear Solid 4 Carman Ng A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 For Iris and Benjamin, my parents and mentors, who have taught me the courage to seek knowledge and truths among warring selves and thoughts. -

Spec Ops: the Line's Conventional Subversion of the Military Shooter

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Keogh, Brendan (2013) Spec Ops: The line’s conventional subversion of the military shooter. In Sharp, J, Pearce, C, & Kennedy, H (Eds.) Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. Digital Games Research Association DiGRA, United States of America, pp. 1-17. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/115527/ c 2013 Authors & Digital Games Research Association DiGRA This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.digra.org/ digital-library/ publications/ spec-ops-the-lines-conventional-subversion-of-the-military-shooter/ Spec Ops: The Line’s Conventional Subversion of the Military Shooter Brendan Keogh School of Media and Communication RMIT University Melbourne, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT The contemporary videogame genre of the military shooter, exemplified by blockbuster franchises like Call of Duty and Medal of Honor, is often criticised for its romantic and jingoistic depictions of the modern, high-tech battlefield. -

Have You Played the War on Terror?

Critical Studies in Media Communication ISSN: 1529-5036 (Print) 1479-5809 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcsm20 Have You Played the War on Terror? Roger Stahl To cite this article: Roger Stahl (2006) Have You Played the War on Terror?, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 23:2, 112-130, DOI: 10.1080/07393180600714489 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07393180600714489 Published online: 16 Aug 2006. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1301 View related articles Citing articles: 33 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcsm20 Download by: [North Carolina State University] Date: 26 July 2016, At: 12:25 Critical Studies in Media Communication Vol. 23, No. 2, June 2006, pp. 112Á130 Have You Played the War on Terror? Roger Stahl The media paradigm by which we understand war is increasingly the video game. These changes are not only reflected in the real-time television war, but also an increased collusion between military and commercial uses of video games. The essay charts the border-crossing of video games between military and civilian spheres alongside attendant discourses of war. Of particular interest are the ways that war has been coded as an object of consumer play and how official productions aimed at training and recruitment have cast video games as players themselves in the War on Terror. The essay argues that this crossover has initialized a ‘‘third sphere’’ of militarized civic space where the citizen is supplanted by the figure of the virtual citizen-soldier. -

Enemy at the Gates

IS IT TRUE? 0. IS IT TRUE? - Story Preface 1. STALINGRAD 2. SOVIET RESISTANCE 3. THE SIEGE OF STALINGRAD 4. VASILY ZAITSEV 5. TANIA CHERNOVA 6. STALINGRAD SNIPERS 7. THE DUEL 8. IS IT TRUE? 9. OPERATION URANUS 10. HITLER FORBIDS SURRENDER 11. GERMAN SURRENDER 12. THE SWORD OF STALINGRAD Most scholars recognize Antony Beevor’s 1998 book, Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege, as the best account of the battle. Beevor interviewed survivors and uncovered extraordinary documents in both German and Russian archives. His monumental work discusses Vasily Zaitsev and his talents as a sniper. But of the duel story, Beevor reports, at page 204: Some Soviet sources claim that the Germans brought in the chief of their sniper school to hunt down Zaitsev, but that Zaitsev outwitted him. Zaitsev, after a hunt of several days, apparently spotted his hide under a sheet of corrugated iron, and shot him dead. The telescopic sight off his prey’s rifle, allegedly Zaitsev’s most treasured trophy, is still exhibited in the Moscow armed forces museum, but this dramatic story remains essentially unconvincing. If the telescopic sight is still on display, and the story made all the papers, why does Beevor think it is not convincing? It is worth noting that there is absolutely no mention of it[the duel] in any of the reports to Shcherbakov [chief of the Red Army political department], even though almost every aspect of ‘sniperism’ was reported with relish. What did Vasily Zaitsev have to say about the duel? Living to old age in the Ukraine, where he was the director of an engineering school in Kiev, this Hero of the Soviet Union was apparently quoted by Alan Clark in Barbarossa: The sun rose. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries WAR The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 Anthropoid DVD-8859 1776 DVD-0397 Apocalypse Now DVD-3440 1900 DVD-4443 DVD-6825 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 Army of Shadows DVD-3022 9th Company DVD-1383 Ashes and Diamonds DVD-3642 Act of Killing DVD-4434 Auschwitz Death Camp DVD-8792 Adams Chronicles DVD-3572 Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi State DVD-7615 Aftermath: The Remnants of War DVD-5233 Bad Voodoo's War DVD-1254 Against the Odds: Resistance in Nazi Concentration DVD-0592 Baghdad ER DVD-2538 Camps Age of Anxiety VHS-4359 Ballad of a Soldier DVD-1330 Al Qaeda Files DVD-5382 Band of Brothers (Discs 1-4) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alexander DVD-5380 Band of Brothers (Discs 5-6) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alive Day Memories: Home from Iraq DVD-6536 Bataan/Back to Bataan DVD-1645 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD-0238 Battle of Algiers DVD-0826 DVD-1284 Battle of Algiers c.4 DVD-0826 c.4 America Goes to War: World War II DVD-8059 Battle of Algiers c.3 DVD-0826 c.3 American Humanitarian Effort: Out-Takes from Vietnam DVD-8130 Battleground DVD-9109 American Sniper DVD-8997 Bedford Incident DVD-6742 DVD-8328 Beirut Diaries and 33 Days DVD-5080 Americanization of Emily DVD-1501 Beowulf DVD-3570 Andre's Lives VHS-4725 Best Years of Our Lives DVD-5227 Anne Frank DVD-3303 Best Years of Our Lives c.3 DVD-5227 c.3 Anne Frank: The Life of a Young Girl DVD-3579 Beyond Treason: What You Don't Know About Your DVD-4903 Government Could Kill You 9/6/2018 Big Red One DVD-2680 Catch-22 DVD-3479 DVD-9115 Cell Next Door DVD-4578 Birth of a Nation DVD-0060 Charge of the Light Brigade (Flynn) DVD-2931 Birth of a Nation and the Civil War Films of D.W. -

Manual Uscod2.Pdf

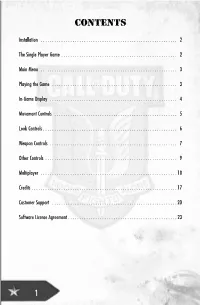

CONTENTS Installation . 2 The Single Player Game . 2 Main Menu . 3 Playing the Game . 3 In-Game Display . 4 Movement Controls . 5 Look Controls . 6 Weapon Controls . 7 Other Controls . 9 Multiplayer . 10 Credits . 17 Customer Support . 20 Software License Agreement . 23 1 INSTALLATION Insert Disc One of Call of Duty ® 2 into your CD/DVD-ROM drive. After a few seconds, the Autorun Menu will appear. Click Install to begin the installation process and follow the on-screen instructions. If the Autorun Menu does not appear, you may have Autorun disabled. Double-click on the My Computer icon on your desktop. Open the CD/DVD-ROM drive where the Call of Duty 2 CD/DVD is located. Double-click on Setup.exe to launch the Installer. If you need more information, please consult the Help files. Enter Key Code To install and run the game, you must have a valid Key Code. Your unique Key Code is located on the back of the manual that came with your game. During installation, please enter the Key Code exactly as it appears on the manual. Keep your copy of the Key Code safe and private in case you need to reinstall the game in the future. No one from Activision® or Infinity Ward will ever ask you for your Key Code. Never give your Key Code to anyone. If you lose your Key Code, you will not be issued another one. • Keep your Key Code in a safe, private place in case you need to reinstall your game at a later point. -

Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review

brain sciences Review Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review 1, , 2,3, 2,4 Denilson Brilliant T. * y, Rui Nouchi y and Ryuta Kawashima 1 Department of Biomedicine, Indonesia International Institute for Life Sciences (i3L), East Jakarta 13210, Indonesia 2 Smart Ageing Research Center (SARC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan; [email protected] (R.N.); [email protected] (R.K.) 3 Department of Cognitive Health Science, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan 4 Department of Functional Brain Imaging, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +62-21-29567888 D.B.T. and R.N. contributed equally to this work. y Received: 18 August 2019; Accepted: 23 September 2019; Published: 25 September 2019 Abstract: Video gaming, the experience of playing electronic games, has shown several benefits for human health. Recently, numerous video gaming studies showed beneficial effects on cognition and the brain. A systematic review of video gaming has been published. However, the previous systematic review has several differences to this systematic review. This systematic review evaluates the beneficial effects of video gaming on neuroplasticity specifically on intervention studies. Literature research was conducted from randomized controlled trials in PubMed and Google Scholar published after 2000. A systematic review was written instead of a meta-analytic review because of variations among participants, video games, and outcomes. Nine scientific articles were eligible for the review. Overall, the eligible articles showed fair quality according to Delphi Criteria.