Witton Gilbert Durham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Councillors N Anderson, M Chard, O Edwards, R Kemp, J Peart, E Wilding, M Wilson and M Wright

BEARPARK PARISH COUNCIL At a meeting of Bearpark Parish Council held on Wednesday 18 October 2017 at 7.00 p.m. Present: Councillors N Anderson, M Chard, O Edwards, R Kemp, J Peart, E Wilding, M Wilson and M Wright. 17/65 ELECTION OF CHAIR The Clerk sought nominations for the position of Chair of the Council, following Councillor Kemp’s decision to vacate the role. The nomination of Councillor M Wright was Moved by Councillor M Wilson, Seconded by Councillor O Edwards Resolved That Councillor M Wright be elected Chair of the Council for the remainder of the 2016/17. Councillor Wright signed the Declaration of Acceptance of Office. Councillor M Wright in the Chair 17/66 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillors E Hull, T Wilson and County Councillor D Bell. 17/67 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest in relation to any item of business on the agenda. 17/68 REPRESENTATIONS FROM THE PUBLIC There were no representations from the public. 17/69 POLICE REPORT The Clerk informed the Council that he had followed up concerns expressed at the previous meeting regarding police presence at meetings and the absence of a police report. A position statement had been circulated to all Councillors via the Clerk, from the Chief Inspector for the area following the representations. The Parish Council expressed their disappointment with the stance that had been taken, particularly with regards to the provision of a report and felt that the issue should be escalated further to the Police and Crime Commissioner. -

Mutual Aid and Community Support – North Durham

Mutual aid and community support – North Durham Category Offer Date and time Contact Catchgate and Annfield Plain Isolation support Coronavirus period Text HELP to 07564 044 509 or email Isolation support If you need support with tasks such as [email protected] 23, Front Street, shopping, collecting prescriptions, Annfield Plain, receiving a friendly call or someone to Stanley check you are ok there are volunteers DH9 7SY to support you. PACT house Stanley Isolation support Coronavirus period Telephone: 07720 650 533 39 Front St, If you need support with tasks such as Stanley shopping, collecting prescriptions, DH9 0JE receiving a friendly call or someone to check you are ok. There are volunteers to support you. Pact House, Home delivery meal and Foodbank Coronavirus period Telephone: 07720 650 533 39 Front Street, support Email: [email protected] Stanley Home Meal delivery for Elderly, County Durham, Vulnerable and people self-isolating, or message on Facebook DH9 0JE. Open access Foodbank running https://www.facebook.com/PACTHouseStanley/ Monday-Friday 10am-4pm, Saturday 11.30am-1.30pm at Stanley Civic hall, The Fulforth Centre, Covid19 Meal support Every Wednesday and Telephone 0191 3710601 and leave a message Front Street, Friday between 1-2pm. email [email protected] Sacriston, Sacriston Parish Council and The Coronavirus period Or contact them through their Facebook page Durham Fulforth Centre will help supply meals https://www.facebook.com/fulforthcentre/ DH7 6JT. to the most vulnerable. All meals will be prepared and cooked within The Fulforth Centre by cooks with relevant Food Hygiene certification. Meals will be supplied two days per week - Wednesday and Friday, commencing Wednesday 8 Mutual Aid Covid-19 is a list of local support groups that have been established during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. -

Handlist 13 – Grave Plans

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Handlist 13 – Grave Plans Issue no. 6 July 2020 Introduction This leaflet explains some of the problems surrounding attempts to find burial locations, and lists those useful grave plans which are available at Durham County Record Office. In order to find the location of a grave you will first need to find which cemetery or churchyard a person is buried in, perhaps by looking in burial registers, and then look for the grave location using grave registers and grave plans. To complement our lists of churchyard burial records (see below) we have published a book, Cemeteries in County Durham, which lists civil cemeteries in County Durham and shows where records for these are available. Appendices to this book list non-conformist cemeteries and churchyard extensions. Please contact us to buy a copy. Parish burial registers Church of England burial registers generally give a date of burial, the name of the person and sometimes an address and age (for more details please see information about Parish Registers in the Family History section of our website). These registers are available to be viewed in the Record Office on microfilm. Burial register entries occasionally give references to burial grounds or grave plot locations in a marginal note. For details on coverage of parish registers please see our Parish Register Database and our Parish Registers Handlist (in the Information Leaflets section). While most burial registers are for Church of England graveyards there are some non-conformist burial grounds which have registers too (please see appendix 3 of our Cemeteries book, and our Non-conformist Register Handlist). -

52 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

52 bus time schedule & line map 52 Durham - East Hedleyhope View In Website Mode The 52 bus line (Durham - East Hedleyhope) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Durham: 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM (2) East Hedleyhope: 8:34 AM - 5:44 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 52 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 52 bus arriving. Direction: Durham 52 bus Time Schedule 66 stops Durham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Turning Circle, East Hedleyhope Tuesday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Deerness View, East Hedleyhope Deerness View, Hedleyhope Civil Parish Wednesday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Old Pit, East Hedleyhope Thursday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Friday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Stable House Farm, East Hedleyhope Saturday 6:49 AM - 4:49 PM Hedley Hill Terrace, Waterhouses Black Horse, Waterhouses Terrace, Waterhouses 52 bus Info Hamilton Row, Brandon And Byshottles Civil Parish Direction: Durham Stops: 66 Church, Waterhouses Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Turning Circle, East Hedleyhope, Old Co-Op Store, Waterhouses Deerness View, East Hedleyhope, Old Pit, East Hedleyhope, Stable House Farm, East Hedleyhope, Station Street, Brandon And Byshottles Civil Parish Hedley Hill Terrace, Waterhouses, Black Horse, Football Ground-Social Club, Waterhouses Waterhouses, Terrace, Waterhouses, Church, Waterhouses, Old Co-Op Store, Waterhouses, Football Ground-Social Club, Waterhouses, College College View, Esh Winning View, Esh Winning, Lymington Crossing, Esh Winning, Co-Operative Store, Esh Winning, -

County Durham Plan Examination Matter 8 (F) - Hearing Statement

County Durham Plan Examination Matter 8 (f) - Hearing Statement Housing Allocations R. Stevenson & Sons (ID: 1014520) Friday, October 18, 2019 © 2019 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd, trading as Lichfields. All Rights Reserved. Registered in England, no. 2778116. 14 Regent’s Wharf, All Saints Street, London N1 9RL Formatted for double sided printing. Plans based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright reserved. Licence number AL50684A 22757/02/NW/LN 17914396v1 County Durham Plan Examination : Matter 8 (f) - Hearing Statement Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Land at Cook Avenue, Bearpark 2 3.0 The Industrial Estate 3 4.0 Accordance with the Plan’s Vision, Objectives and Overall Spatial Strategy 4 Vision 4 Objectives 4 Spatial Strategy 6 5.0 Availability 7 6.0 Viability and Market Interest 8 County Durham Plan Examination : Matter 8 (f) - Hearing Statement Appendices Appendix 1 Accessibility Credentials Appendix 2 Photos of the Industrial Units Appendix 3 Letter from JW Wood Appendix 4 Letter from H&H Appendix 5 Email from Taylor Wimpey County Durham Plan Examination : Matter 8 (f) - Hearing Statement 1.0 Introduction Are the housing allocations proposed in policy 4 (Table 7) and shown on the policies map justified? In particular, are they in suitable locations in the context of the Plan’s vision, objectives and overall spatial strategy, and is there a reasonable prospect that they will be available and could be viably developed at the point envisaged? Are the site specific requirements set out in Table 7 justified? 1.1 Thank you for providing us with the opportunity to submit a Hearing Statement in relation to Matter 8 ‘Housing Allocations’ on behalf of our client, R Stevenson & Sons, regarding their land holdings at Cook Avenue, Bearpark, which has a draft allocation for 200 dwellings (Ref: H7). -

County Durham Plan Examination - Hearing Statement Matter 8: Housing Land Supply Barratt David Wilson Homes

County Durham Plan Examination - Hearing Statement Matter 8: Housing Land Supply Barratt David Wilson Homes a) Commitments Is the assumption in Table 2 in the Plan that 15,946 homes will be provided on ‘commitments as at 30 September 2018’ justified? BDW do not consider that the commitments as at September 2018 are justified as a large number of are unlikely to ever come forward for the following reasons: 1. The Council state that ‘…it is unlikely that all of these [commitments] will come forward during the Plan period for a variety of reasons such as abnormal costs, including land contamination, or a lack of house builder interest’ (paragraph 24, Housing Need and Residual for Allocation and Evidence Paper 2. Historically, based on the councils own evidence, 17% of sites with permission have lapsed (paragraph 25, Housing Need and Residual for Allocation and Evidence Paper). 3. The Council’s evidence base also states that 2,159 houses included with the commitments, were at committee more than 6 months ago. In some cases, these unresolved S106 agreement cases are 10 years old (paragraph 37, Housing Need and Residual for Allocation and Evidence Paper). It should be noted that the majority of these applications will not be compliant with the emerging plan, for example compliance with NDSS and provision of older person housing, and as such may not be suitable for approval following adoption of the Local Plan. This clearly demonstrates that there are numerous issues associated with the 15,946 homes identified in table 2 and their contribution to future delivery is far from guaranteed. -

Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, Newhouse, Esh Winning

West Durham Catholic Parishes: Esh, Esh Winning, Langley Park and Ushaw Moor St John Boste Pastoral Office, Durham Road, Ushaw Moor, Durham. DH7 7LF Priest: Father David Coxon Tel: (0191) 373 0219 Secretary: Lisa Hatton Tel: (0191) 373 0219 Office Hours: Tues – Thurs from 9.30am–2.30pm E-mail: [email protected] Website: wdrcp.org Primary Schools: St Joseph’s, Ushaw Moor: Tel. (0191) 373 0355 Our Lady Queen of Martyrs, Esh Winning: Tel. (0191) 373 4343 St Michael’s Esh Laude: Tel. (0191) 373 1205 Hospital R C Chaplain Father Paul Tully Tel. (01388) 818544 Please telephone the Chaplain if you have someone in hospital who would like a visit. St Joseph’s St Michael’s Our Lady Queen of St Joseph’s Langley Ushaw Moor Esh Laude Martyrs, Newhouse Park Saturday 9 February 6.00 pm Mass Jackson & Bullen Family , Patricia Edwards & People of the Parish Sunday 10 February 9.00 am Mass 10.30 am Mass 5th Sunday of the Year James and Anne Paul Boddice (sick) Redmond, Teresa Rochford & Maggie Rowntree & People of the Parish People of the Parish Monday 11 February Tuesday 12 February 6.15 pm Confessions 7.00 pm Mass Anne Cutmore Wed 13 February 9.15 am Mass School Chapel Priest’s Intention Thurs 14 February 9.15 am Mass SS Cyril, Monk & Methodius Priest’s Intention Bp Patrons of Europe Friday 15 February 9.15 am Mass Aileen Cook Saturday 16 February 6.00 pm Mass Catherine O’Neil & People of the Parish Sunday 17 February 9.00 am Mass 10.30 am Mass 6th Sunday of the Year People of the Parish Michael & Mary Ann Peel, Nora Stiff & People of the Parish Sick: Ann Waugh, Faith Wilthew, Caitlin Minnis and Monica Mitten from Ushaw Moor. -

Town and Parish Council Submissions to the Durham County Council Electoral Review

Town and parish council submissions to the Durham County Council electoral review This PDF document contains 34 submissions from town and parish councils in County Durham. Some versions of Adobe Acrobat allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. From: Marion Wilson Sent: 21 July 2011 14:28 To: Reviews@ Subject: Co. Durham Boundary Changes/ Bearpark RE: CO.DURHAM BOUNDARY CHANGES. BEARPARK Dear Sir, Bearpark Parish Council would welcome a change in the electoral arrangements whereby Bearpark would be incorporated into the Deerness Ward as local amenities and services (such as schools and bus routes) and strong community links are shared by residents within the electoral division. Yours Sincerely Mrs. Marion Wilson Chair Bearpark Parish Council From: JOHN IRVINE Sent: 04 July 2011 00:01 To: Reviews@ Subject: Suggested boundary changes-Fishburn, Co Durham Hello, I have been asked to write on behalf of Fishburn Parish Council, but I also write as a resident of Fishburn myself, to object strongly to the proposals that link Fishburn in with Sedgefield as opposed to the Trimdons. In the first draft of proposed changes, no suggestion was made that Fishburn would be affected. As a result of Bishop Middleham and West Cornforth wanting change, Fishburn suddenly gets moved, as it has on several occasions in the past. Fishburn people are generally unaware that this change is about to happen, and I notice no-one from Fishburn commented on the first or second draft of proposals. -

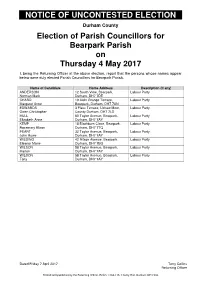

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON 12 South View, Bearpark, Labour Party Norman Mark Durham, DH7 7DE CHARD 19 Aldin Grange Terrace, Labour Party Margaret Anne Bearpark, Durham, DH7 7AN EDWARDS 3 Flass Terrace, Ushaw Moor, Labour Party Owen Christopher County Durham, DH7 7LD HULL 60 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Elizabeth Anne Durham, DH7 7AY KEMP 18 Blackburn Close, Bearpark, Labour Party Rosemary Alison Durham, DH7 7TQ PEART 32 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party John Howe Durham, DH7 7AY WILDING 42 Ritson Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Eleanor Marie Durham, DH7 7BG WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Marion Durham, DH7 7AY WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Tony Durham, DH7 7AY Dated Friday 7 April 2017 Terry Collins Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Room 1/104-115, County Hall, Durham, DH1 5UL NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) COOKE 5 High Road, Bishop Middleham, -

Results of Lib Dem Survey on County Durham Plan

RESULTS OF LIB DEM SURVEY ON COUNTY DURHAM PLAN Several thousand surveys were delivered by the Lib Dems to the West of Durham City in Newton Hall, Brasside, Witton Gilbert, Pity Me and Framwellgate Moor to get views on Durham County Council’s proposals for new housing, the development of Aykley Heads, and proposals for two relief roads. In addition the survey was advertised in the local press and residents from other parts of the area also made contributions. A full survey of Bearpark has yet to be carried out, as we are waiting for a consultation meeting in the village, currently penciled in for April 17 th 3.30pm to 7.30pm, mainly centred around the Western relief Road issues. Separate information about responses to housing in Witton Gilbert are being provided to the Council in a separate document. Over 300 people responded and hundreds of comments related to the County Durham Plan and Consultation are detailed in this report. In addition a separate survey was conducted by the Lib Dems in Neville’s Cross relating to the Western Relief Road and other local issues which had over 200 responses but is not included in this report. The comments in this report are entirely from residents and should not be taken as representing the views of the County Council or any political group. Mark Wilkes – County Councillor, Framwellgate Moor Division Amanda Hopgood – County Councillor, Newton Hall Division Mamie Simmons – County Councillor, Newton Hall Division BRIEF OVERVIEW OF RESPONSES • Over 80% against proposals for housing on greenbelt. • Over 80% feel Durham County Council hasn’t consulted properly on the plans • Over 60% in favour of Western Relief Road • Nearly 70% in favour of Northern Relief Road • Residents split nearly 50-50 on proposals for Aykley Heads • New housing should be family homes and first-time buyer homes with strong view that this housing should be eco-friendly. -

Durham City Liberal Democrats Wish to Submit the Following Proposals for Consideration As Amended Electoral Divisions for the New Unitary Council

BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL BOUNDARY REVIEW: DURHAM COUNTY COUNCIL LIBERAL DEMOCRAT PROPOSAL Durham City Liberal Democrats wish to submit the following proposals for consideration as amended electoral divisions for the new Unitary Council. Context The proposals are based on the following criteria: The number of councillors will remain at 126. Wherever possible the divisions will have two members, though one and three member wards may be created to satisfy other criteria (see below). The electorate of each division will normally be within a tolerance of plus or minus 10% of the County average of 6,373 electors i.e. from 5,738 to 7,010. Data is derived from County projections for 2013 plus the corrected student numbers (see below). Division boundaries will respect parish boundaries and where they are not co- terminus will follow parish ward boundaries. Exceptionally, new parish wards may be created. Natural communities to form the basic building blocks of the divisions. Proposals for Durham City The proposals for Durham City satisfy the above criteria more closely than other suggestions. Change is kept to a minimum, numerical anomalies evened out, and an even stronger sense of community is delivered than with the existing boundaries. A brief commentary is provided after each Divisional description. Student Adjustments The projections to 2013 in some central polling districts are affected by changes in the rules for voter registration which removed registration from members of a household that failed to reconfirm after 12 months. Durham University is a powerful presence in the City’s housing market. The majority of student rented houses appear to have been significantly affected by this ruling, resulting in significant reductions in registration numbers between 2004 and 2008 (e.g. -

North Durham

Mutual aid and community support – North Durham Category Offer Date and time Contact Catchgate and Annfield Plain Isolation support Coronavirus period Text HELP to 07564 044 509 or email Isolation support If you need support with tasks such as [email protected] 23, Front Street, shopping, collecting prescriptions, Annfield Plain, receiving a friendly call or someone to Stanley check you are ok there are volunteers DH9 7SY to support you. PACT house Stanley Isolation support Coronavirus period Telephone: 07720 650 533 39 Front St, If you need support with tasks such as Stanley shopping, collecting prescriptions, DH9 0JE receiving a friendly call or someone to check you are ok. There are volunteers to support you. Pact House, Home delivery meal and Foodbank Coronavirus period Telephone: 07720 650 533 39 Front Street, support Stanley Email: [email protected] County Durham, Home Meal delivery for Elderly, or message on Facebook Vulnerable and people self-isolating, DH9 0JE. https://www.facebook.com/PACTHouseStanley/ Open access Foodbank running Monday-Friday 10am-4pm, Saturday 11.30am-1.30pm at Stanley Civic hall, The Fulforth Centre, Every Wednesday and Telephone 0191 3710601 and leave a message Front Street, Covid19 Meal support Friday between 1-2pm. email [email protected] Sacriston, Coronavirus period Or contact them through their Facebook page Sacriston Parish Council and The Durham Fulforth Centre will help supply meals https://www.facebook.com/fulforthcentre/ DH7 6JT. to the most vulnerable. Mutual Aid Covid-19 is a list of local support groups that have been established during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. To find a local group visit https://www.mutual-aid.co.uk/ Mutual aid and community support – North Durham Category Offer Date and time Contact All meals will be prepared and cooked within The Fulforth Centre by cooks with relevant Food Hygiene certification.