Bug-Eyed: Art, Culture, Insects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evening with Alexis Rockman

Press Release Bruce Museum Presents Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change? An Evening with Alexis Rockman Acclaimed artist to be joined by David Abel, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The Boston Globe 6:30 – 8:30 pm, December 5, 2019 Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut Alexis Rockman, The Farm, 2000. Oil and acrylic on wood panel, 96 x 120 in. GREENWICH, CT, November 4, 2019 — On Thursday, December 5, 2019, Bruce Museum Presents poses the provocative question “Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change?” Leading the conversation is acclaimed artist and climate-change activist Alexis Rockman, who will present specially chosen examples of his work and discuss how, and why, he uses his art to sound the alarm about the impending global emergency. Adding insight and his own expert perspective is The Boston Globe’s David Abel, who since 1999 has reported on war in the Balkans, unrest in Latin America, national security issues in Washington D.C., and climate change and poverty in New England. Page 1 of 3 Press Release Abel was also part of the team that won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News for the paper’s coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings. He now covers the environment for the Globe. Following Rockman’s presentation, Abel will join Rockman for a wide-ranging dialogue at the intersection of art and environmental activism, followed by question-and-answer session with the audience. Among the current generation of American artists profoundly motivated by nature and its future—from the specter of climate change to the implications of genetic engineering—Rockman holds an unparalleled place of honor. -

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40049989 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION A dissertation presented by DANNY HAELEWATERS to THE DEPARTMENT OF ORGANISMIC AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2018 ! ! © 2018 – Danny Haelewaters All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor Donald H. Pfister Danny Haelewaters STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION ABSTRACT CHAPTER 1: Laboulbeniales is one of the most morphologically and ecologically distinct orders of Ascomycota. These microscopic fungi are characterized by an ectoparasitic lifestyle on arthropods, determinate growth, lack of asexual state, high species richness and intractability to culture. DNA extraction and PCR amplification have proven difficult for multiple reasons. DNA isolation techniques and commercially available kits are tested enabling efficient and rapid genetic analysis of Laboulbeniales fungi. Success rates for the different techniques on different taxa are presented and discussed in the light of difficulties with micromanipulation, preservation techniques and negative results. CHAPTER 2: The class Laboulbeniomycetes comprises biotrophic parasites associated with arthropods and fungi. -

Michael Heizer Selected Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Michael Heizer Selected Bibliography Selected Books and Catalogues: 2019 Fox, William. Michael Heizer: The Once and Future Monuments. New York: Monacelli Press. 2017 Voorhies, James. Beyond Objecthood: The Exhibition as a Critical Form since 1968. Boston: MIT Press. Celant, Germano and Chiara Costa. Virginia Dwan: Dwan Gallery. Lausanne: Skira. 2015 Fine, Ruth E., Kara Vander Weg and Michael Heizer. Michael Heizer: Altars. New York: Gagosian Gallery. 2014 Cameron, Dan. The Avant-Garde Collection. Newport Beach, CA: Orange County Museum of Art. Kaz, Leonel, ed. Inusitada Coleção De Sylvio Perlstein. São Paolo: Museu de Arte de São Paolo Assis Chateaubriand. 2013 Allen, Gwen L., Pierre Bal Blanc, Claire Bishop, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Charles Esche, et al. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013. Milan: Fondazione Prada. 2012 Lippard, Lucy R. and Jeff Khonsary. 4,492,040 (1969–74). Vancouver: New Documents 2010 Jensen, Susanne, Susanne Lenze, and Reinhard Onnasch. “Michael Heizer: Untitled.” In Nineteen Artists. Berlin: El Sourdog Hex; Bielefeld, Germany: Kerber Verlag. 2011 Reifenscheid, Beate. Die Letzte Freiheit: Von den Pionieren der Land-Art der 1960er Jahre bis zur Natur im Cyberspace. Milan: Silvana. 2010 Goldman, Judith. Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection. New York: Acquavella Gallery. Marcoci, Roxana, ed. The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today. New York: Museum Of Modern Art. 2009 Grabner, Roman, Thomas Kellein, and Felicitas von Richthofen. 1968: Die Große Unschuld. Cologne: DuMont. 2008 Semff, Michael. Künstler Zeichnen. Sammler Stiften, 250 Jahre Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz. Lara, Cathy, ed. -

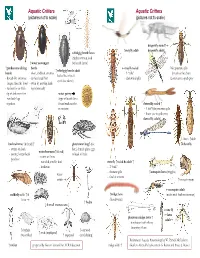

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

The Mayfly Newsletter: Vol

Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 1-9-2018 The aM yfly Newsletter Donna J. Giberson The Permanent Committee of the International Conferences on Ephemeroptera, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mayfly Part of the Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, Systems Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Giberson, Donna J. (2018) "The aM yfly eN wsletter," The Mayfly Newsletter: Vol. 20 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mayfly/vol20/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Newsletters at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mayfly eN wsletter by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mayfly Newsletter Vol. 20(2) Winter 2017 The Mayfly Newsletter is the official newsletter of the Permanent Committee of the International Conferences on Ephemeroptera In this issue Project Updates: Development of new phylo- Project Updates genetic markers..................1 A new study of Ephemeroptera Development of new phylogenetic markers to uncover island in North West Algeria...........3 colonization histories by mayflies Sereina Rutschmann1, Harald Detering1 & Michael T. Monaghan2,3 Quest for a western mayfly to culture...............................4 1Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Immunology, University of Vigo, Spain 2Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Berlin, Germany 3 Joint International Conf. Berlin Center for Genomics in Biodiversity Research, Berlin, Germany Items for the silent auction at Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] the Aracruz meeting (to sup- port the scholarship fund).....6 The diversification of evolutionary young species (<20 million years) is often poorly under- stood because standard molecular markers may not accurately reconstruct their evolutionary How to donate to the histories. -

The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D

Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Selected Papers from the Conference held at DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Editors: Barb Willard DePaul University Chris Green DePaul University Host: DePaul University, College of Communication Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Edited by: Barbara E. Willard Chris Green College of Communication Humanities Center DePaul University DePaul University Editorial Assistant: Joy Dinaro College of Communication DePaul University Arash Hosseini College of Communication DePaul University Publication Date: August 11, 2008 Publisher of Record: College of Communication, DePaul University, 2320 N. Kenmore Ave., Chicago, IL 60614 (773)325-2965 Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture: Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Barb Willard and Chris Green, editors Table of Contents i - iv Conference Program vi-xii Preface and Acknowledgements xiii – xvi Twenty-Five Years After the Die is Cast: Mediating the Locus of the Irreparable From Awareness to Action: The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D. Besel, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Love, Guilt and Reparation: Rethinking the Affective Dimensions of the Locus of the 8 - 13 Irreparable Renee Lertzman, Cardiff University, UK Producing, Marketing, Consuming & Becoming Meat: Discourse of the Meat at the Intersections of Nature and Culture Burgers, Breasts, and Hummers: Meat and Masculinity in Contemporary Television 14 – 24 Advertisements Richard A. -

Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts

Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts September 15, 2013 This report is the result of several years of field data collection, analyses and IBI development, and consideration of the opportunities for wetland program and policy development in relation to IBIs and CAPS Index of Ecological Integrity (IEI). Contributors include: University of Massachusetts Amherst Kevin McGarigal, Ethan Plunkett, Joanna Grand, Brad Compton, Theresa Portante, Kasey Rolih, and Scott Jackson Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management Jan Smith, Marc Carullo, and Adrienne Pappal Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Lisa Rhodes, Lealdon Langley, and Michael Stroman Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts Abstract The purpose of this study was to develop a fully empirically-based method for developing Indices of Biotic Integrity (IBIs) that does not rely on expert opinion or the arbitrary designation of reference sites and pilot its application in forested wetlands, coastal salt marshes and wadable freshwater streams in Massachusetts. The method we developed involves: 1) using a suite of regression models to estimate the abundance of each taxon across a gradient of stressor levels, 2) using statistical calibration based on the fitted regression models and maximum likelihood methods to predict the value of the stressor metric based on the abundance of the taxon at each site, 3) selecting taxa in a forward stepwise procedure that conditionally improves the concordance between the observed stressor value and the predicted value the most and a stopping rule for selecting taxa based on a conditional alpha derived from comparison to pseudotaxa data, and 4) comparing the coefficient of concordance for the final IBI to the expected distribution derived from randomly permuted data. -

Yellow Mayfly (Potamanthus Luteus )

SPECIES MANAGEMENT SHEET Yellow mayfly (Potamanthus luteus ) The Yellow mayfly is one of Britain’s rarest mayflies. The nymphs or larvae of this mayfly typically live in silt trapped amongst stones on the riverbed in pools and margins and grow to between 15 and 17mm. They are streamlined with seven pairs of thick feathery gills that are held outwards from their sides. The adults have three tails and large hindwings. The body is a dull yellowish-orange with a distinctive broad yellowish brown stripe along the back. The wings are yellow and the cross-veins are a dark reddish colour. Due to its rarity and decline in numbers this insect has been made a Priority Species on the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP). Life cycle There is one generation of this mayfly a year which overwinters as larvae. The adult mayflies are short lived and emerge between May and late October (with peak emergence in July). They will typically emerge at dusk and usually from the surface of the water, although they may also emerge by climbing up stones or plant stems partially or entirely out of water. Distribution map This mayfly is historically a rare species with populations in the River Wye and Usk, Herefordshire. The most recent surveys show a dramatic decline in the River Wye population and have failed to find this species in the River Usk. A small population has however recently been found in the River Teme in Worcestershire. Habitat In the Herefordshire streams where this species has been found, the larvae have been found under loose stones, preferring mobile sections of shingle or a mixture of larger stones with loose shingle such as those found downstream of bridges or at the confluence of tributaries. -

Variability and Distribution of the Golden-Headed Weevil Compsus Auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini)

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Single Taxon Treatment Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini) Jennifer C. Girón‡, M. Lourdes Chamorro§ ‡ Natural Science Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, United States of America § Systematic Entomology Laboratory, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States of America Corresponding author: Jennifer C. Girón ([email protected]) Academic editor: Li Ren Received: 15 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 03 Jul 2020 | Published: 09 Jul 2020 Citation: Girón JC, Chamorro ML (2020) Variability and distribution of the golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus (Say) (Curculionidae: Entiminae: Eustylini). Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55474. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55474 Abstract Background The golden-headed weevil Compsus auricephalus is a native and fairly widespread species across the southern U.S.A. extending through Central America south to Panama. There are two recognised morphotypes of the species: the typical green form, with pink to cupreous head and part of the legs and the uniformly white to pale brown form. There are other Central and South American species of Compsus and related genera of similar appearance that make it challenging to provide accurate identifications of introduced species at ports of entry. New information Here, we re-describe the species, provide images of the habitus, miscellaneous morphological structures and male and female genitalia. We discuss the morphological variation of Compsus auricephalus across its distributional range, by revising and updating This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

Small Genome Symbiont Underlies Cuticle Hardness in Beetles

Small genome symbiont underlies cuticle hardness in beetles Hisashi Anbutsua,b,1,2, Minoru Moriyamaa,1, Naruo Nikohc,1, Takahiro Hosokawaa,d, Ryo Futahashia, Masahiko Tanahashia, Xian-Ying Menga, Takashi Kuriwadae,f, Naoki Morig, Kenshiro Oshimah, Masahira Hattorih,i, Manabu Fujiej, Noriyuki Satohk, Taro Maedal, Shuji Shigenobul, Ryuichi Kogaa, and Takema Fukatsua,m,n,2 aBioproduction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tsukuba 305-8566, Japan; bComputational Bio Big-Data Open Innovation Laboratory, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan; cDepartment of Liberal Arts, The Open University of Japan, Chiba 261-8586, Japan; dFaculty of Science, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan; eNational Agriculture and Food Research Organization, Kyushu Okinawa Agricultural Research Center, Okinawa 901-0336, Japan; fFaculty of Education, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan; gDivision of Applied Life Sciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; hGraduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, Chiba 277-8561, Japan; iGraduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, Waseda University, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan; jDNA Sequencing Section, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Okinawa 904-0495, Japan; kMarine Genomics Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Okinawa 904-0495, Japan; lNIBB Core Research Facilities, National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan; mDepartment of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan; and nGraduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8572, Japan Edited by Nancy A. Moran, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved August 28, 2017 (received for review July 19, 2017) Beetles, representing the majority of the insect species diversity, are symbiont transmission over evolutionary time (4, 6, 7). -

Investigation of the Selective Color-Changing Mechanism

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Investigation of the selective color‑changing mechanism of Dynastes tityus beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Jiyu Sun1, Wei Wu2, Limei Tian1*, Wei Li3, Fang Zhang3 & Yueming Wang4* Not only does the Dynastes tityus beetle display a reversible color change controlled by diferences in humidity, but also, the elytron scale can change color from yellow‑green to deep‑brown in specifed shapes. The results obtained by focused ion beam‑scanning electron microscopy (FIB‑SEM), show that the epicuticle (EPI) is a permeable layer, and the exocuticle (EXO) is a three‑dimensional photonic crystal. To investigate the mechanism of the reversible color change, experiments were conducted to determine the water contact angle, surface chemical composition, and optical refectance, and the refective spectrum was simulated. The water on the surface began to permeate into the elytron via the surface elemental composition and channels in the EPI. A structural unit (SU) in the EXO allows local color changes in varied shapes. The refectance of both yellow‑green and deep‑brown elytra increases as the incidence angle increases from 0° to 60°. The microstructure and changes in the refractive index are the main factors that infuence the process of reversible color change. According to the simulation, the lower refectance causing the color change to deep‑brown results from water infltration, which increases light absorption. Meanwhile, the waxy layer has no efect on the refection of light. This study lays the foundation to manufacture engineered photonic materials that undergo controllable changes in iridescent color. Te varied colors of nature have a great visual impact on human beings. -

At Play Spring-Summer 06.Indd

rating Seventy Y representing the american theatre by eleb ears publishing and licensing the works C of new and established playwrights 70th Anniversary Issue D ram 06 ati – 20 sts Play Service, Inc. 1936 Issue 12, Spring/Summer 2006 AN INTERVIEW WITH Austin Pendleton Director of Professional Rights Robert Lewis Vaughan and Director of Publications Michael Q. Fellmeth talk with Austin Pendleton about his New York hit, Orson’s Shadow, and his life as a consummate man of the theatre. ROBERT. Orson’s Shadow had an amazing run here in New York at The Barrow Street Theatre following Tracy Letts’ fantastic Bug (also represented by DPS). Tracy was in your play, in the role of Kenneth Tynan. Two hits in a row — two actor/playwrights in a row — one theatre. What do you have to say about that? AUSTIN. There’s more to it than that. Tracy Letts caused this to happen. He told our producers (Scott Morfee, Chip Meyrelles, Tom Wirtshafter) about Orson’s Shadow. He put together a reading with the Chicago cast, directed by the Chicago director, in Chicago, for Scott, Chip and Tom to come and see and hear … Continued on page 3 NEWPLAYS Serving the American Theatre Since 1936: A Brief History of Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Rob Ackerman DISCONNECT. Goaded by the women they love “The Dramatists Play Service came into being at exactly the right moment and haunted by memories they can no longer for the contemporary playwright and the American theatre at large.” suppress, two men at a dinner party confront the —Audrey Wood, renowned agent to Tennessee Williams lies of their lives.