WILMA A. IGGERS (Buffalo, NY, USA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klaus Johann Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3

Klaus Johann Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3. XI. 2010) 1. a.d. (KK): Die siebzehn Reisen Goethes nach Böhmen. [Rezension der erweiterten Neuauflage von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Aufbau (New York). 16. VII. 1982. 2. A.S.: Johannes Urzidil liest. Zimmertheater Heddy Maria Wettstein. In: Die Tat. 17. X. 1970. 3. Abendroth, Friedrich [i.e. Friedrich Weigend-Abendroth] : „Die Erbarmungen Gottes“. [Rezension der Neuausgabe von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Die Furche. Nr. 38. 22. IX. 1962. S.11. 4. Abendroth, Friedrich: Erzählen ist nicht mehr erlaubt? In: Echo der Zeit. 30. X. 1966. 5. Abendroth, Friedrich: Ein böhmisches Buch. [Rezension von Johannes Urzidil, „Die verlorene Geliebte“.] In: Die Furche. Nr.39. 22. IX. 1956. Beilage „Der Krystall“. S.3. 6. Adam, Franz: Mit Franz Kafka saß er im Café. Tagung des Ostdeutschen Kulturrats über Johannes Urzidil. In: Kulturpolitische Korrespondenz. 1037. 5. April 1998. S.11-13. 7. Adler, H. G.: Die Dichtung der Prager Schule. [EA: 1976.] Vorw. v. Jeremy Adler. Wuppertal u. Wien: Arco 2010. ( = Coll’Arco.<FA>3) 8. ag: Ein Dichter Böhmens. Zu einer Vorlesung Johannes Urzidils. In: Stutt- garter Zeitung. 22. XI. 1962. 9. Ahl, Herbert: Ein Historiker seiner Visionen. Johannes Urzidil . In: H.A.: Litera- rische Portraits. München u. Wien: Langen Müller 1962. S.164-172. 10. ak: Vergangenes. [Rezension der Heyne-Taschenbuchausgabe von „Prager Triptychon“.] In: Deutsche Tagespost. 27. VI. 1980. 11. Albers, Heinz: Wie der Freund ihn sah. Johannes Urzidil im Hamburg Cen- trum über Kafka. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. 2. X. 1970. 12. Alexander, Manfred: Einleitung. In: M.A. (Hg.): Deutsche Gesandtschaftsbe- richte aus Prag. -

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, Kritiker und Künstler Antiquariat Frank Albrecht · [email protected] 69198 Schriesheim · Mozartstr. 62 · Tel.: 06203/65713 Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 D Verlag und A Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, S Antiquariat Kritiker und Künstler 2 Frank 0. J A Albrecht H Inhalt R H Belletristik ....................................................................... 1 69198 Schriesheim U Sekundärliteratur ........................................................... 31 Mozartstr. 62 N Kunst ............................................................................. 35 Register ......................................................................... 55 Tel.: 06203/65713 D FAX: 06203/65311 E Email: R [email protected] T USt.-IdNr.: DE 144 468 306 D Steuernr. : 47100/43458 Die Abbildung auf dem Vorderdeckel A zeigt eine Original-Zeichnung von S Joachim Ringelnatz (Katalognr. 113). 2 0. J A H Spezialgebiete: R Autographen und H Widmungsexemplare U Belletristik in Erstausgaben N Illustrierte Bücher D Judaica Kinder- und Jugendbuch E Kulturgeschichte R Unser komplettes Angebot im Internet: Kunst T http://www.antiquariat.com Politik und Zeitgeschichte Russische Avantgarde D Sekundärliteratur und Bibliographien A S Gegründet 1985 2 0. Geschäftsbedingungen J Mitglied im Alle angebotenen Bücher sind grundsätzlich vollständig und, wenn nicht an- P.E.N.International A ders angegeben, in gutem Erhaltungszustand. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro und im Verband H (€) inkl. Mehrwertsteuer. -

Rudolf Abraham

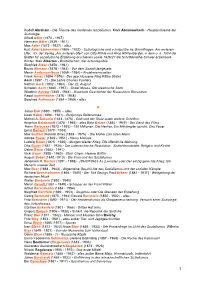

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

München Liest

Die verbrannten Dichter: „Die Waffen nieder!“ (Bertha von Suttner) Nathan Asch - Martin Andersen-Nexö - Ernst Barlach - Oskar Baum - Vicki Baum - Johannes R. Becher - Walter Benjamin - Martin Beradt - Eduard Bernstein - Franz Blei - Bertolt Brecht - Willi Bredel - Joseph Breitbach - Max Brod - Ferdinand Bruckner - Elias Canetti - Veza Canetti - Elisabeth Castonier - Franz Th. Csokor - Alfred Döblin - John Dos Passos - Kasimir Edschmid - Hans Fallada - Lion Feuchtwanger - Marieluise Fleißer - Bruno Frank - Leonhard Frank - Anna Freud - Sigmund Freud - Egon Friedell - Richard Friedenthal -Claire Goll - Maxim Gorki - Oskar Maria Graf - Karl Grünberg - Willy Haas - Hans Habe - Jakob Haringer - Walter Wenn Sie fünf Minuten aus einem Hasenclever - Georg Hermann - Franz Hessel - “verbrannten Buch” vorlesen möchten, Ödön von Horvath - Oskar Jellinek - Erich Kästner - rufen Sie bitte an unter Franz Kafka - Mascha Kaleko - Gina Kaus - Hermann 089 - 157 32 19. Kesten - Irmgard Keun - Egon Erwin Kisch - Klabund - Annette Kolb - Gertrud Kolmar - Paul Kornfeld - Theodor Kramer - Else Lasker-Schüler - Maria Veranstalter: Leitner - Theodor Lessing - Jack London - Emil - Institut für Kunst und Forschung, München, Ludwig - Heinrich Mann - Klaus Mann - Thomas Wolfram P. Kastner, Tel. 089 - 157 32 19 Mann - Valeriu Marcu - Walter Mehring - Konrad Merz - Max Mohr - Erich Mühsam - Hans Natonek - Mitveranstalter: - Landeshauptstadt München, Max Hermann Neiße - Alfred Neumann - Robert Kulturreferat und Referat fur Bildung und Sport Neumann - Leo Perutz - Carl -

Walt Whitman

CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN WALT WHITMAN CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN Walt Whitman BY WALTER GRUNZWEIG UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS 1!11 IOWA CITY University oflowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 1995 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gri.inzweig, Walter. Constructing the German Walt Whitman I by Walter Gri.inzweig. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87745-481-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-87745-482-5 (paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892-Appreciation-Europe, German-speaking. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892- Criticism and interpretation-History. 3. Criticism Europe, German-speaking-History. I. Title. PS3238.G78 1994 94-30024 8n' .3-dc2o CIP 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 c 5 4 3 2 1 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 p 5 4 3 2 1 To my brother WERNER, another Whitmanite CONTENTS Acknowledgments, ix Abbreviations, xi Introduction, 1 TRANSLATIONS 1. Ferdinand Freiligrath, Adolf Strodtmann, and Ernst Otto Hopp, 11 2. Karl Knortz and Thomas William Rolleston, 20 3· Johannes Schlaf, 32 4· Karl Federn and Wilhelm Scholermann, 43 5· Franz Blei, 50 6. Gustav Landauer, 52 7· Max Hayek, 57 8. Hans Reisiger, 63 9. Translations after World War II, 69 CREATIVE RECEPTION 10. Whitman in German Literature, 77 11. -

Franz Werfel Papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt800007v5 No online items Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 Finding aid prepared by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 15 December 2017. Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 1 LSC.0512 Title: Franz Werfel papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0512 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 18.5 linear feet(37 boxes and 1 oversize box) Date: 1910-1944 Abstract: Franz Werfel (1890-1945) was one of the founders of the expressionist movement in German literature. In 1940, he fled the Nazis and settled in the U.S. He wrote one of his most popular novels, Song of Bernadette, in 1941. The collection consists of materials found in Werfel's study at the time of his death. Includes correspondence, manuscripts, clippings and printed materials, pictures, artifacts, periodicals, and books. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the request button located on this page. Werfel's desk on permanent loan to the Villa Aurora in Pacific Palisades. Creator: Werfel, Franz, 1890-1945 Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

V E R B R a N N T V E R B O T E N V E R B a N

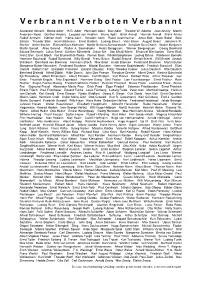

V e r b r a n n t V e r b o t e n V e r b a n n t Alexander Abusch Bruno Adler H.G. Adler Hermann Adler Max Adler Theodor W. Adorno Jean Améry Martin Andersen Nexö Günther Anders Leopold von Andrian Bruno Apitz Erich Arendt Hannah Arendt Frank Arnau Rudolf Arnheim Nathan Asch Käthe Asch Schalom Asch Raoul Auernheimer Julius Bab Isaak Babel Béla Balázs Theodor Balk Henri Barbusse Ernst Barlach Ludwig Bauer Vicki Baum August Bebel Johannes R. Becher Ulrich Becher Richard Beer-Hofmann Martin Beheim-Schwarzbach Schalom Ben-Chorin Walter Benjamin Martin Beradt Alice Berend Walter A. Berendsohn Heinz Berggruen Werner Bergengruen Georg Bernhard Eduard Bernstein Julius Berstl Günther Birkenfeld Oskar Bie Oto Bihalji-Merin Emanuel Bin-Gorion Ernst Blaß Franz Blei Ernst Bloch Ilse Blumenthal-Weiss Werner Bock Nikolai Bogdanow Ludwig Börne Waldemar Bonsels Hermann Borchardt Rudolf Borchardt Willy Brandt Franz Braun Rudolf Braune Bertolt Brecht Willi Bredel Joseph Breitbach Bernhard von Brentano Hermann Broch Max Brod Arnolt Bronnen Ferdinand Bruckner Martin Buber Margarete Buber-Neumann Ferdinand Bruckner Nikolai Bucharin Hermann Budzislawski Friedrich Burschell Elias Canetti Robert Carr Elisabeth Castonier Eduard Claudius Franz Theodor Csokor Julius Deutsch Otto Deutsch Bernhard Diebold Alfred Döblin Hilde Domin John Dos Passos Theodore Dreiser Albert Drach Kasimir Edschmid Ilja Ehrenburg Albert Ehrenstein Albert Einstein Carl Einstein Kurt Eisner Norbert Elias Arthur Eloesser Lex Ende Friedrich Engels Fritz Erpenbeck Hermann Essig Emil Faktor Lion Feuchtwanger Ernst Fischer Ruth Fischer Eugen Fischer-Baling Friedrich-Wilhelm Förster Heinrich Fraenkel Bruno Frank Leonhard Frank Bruno Frei Sigmund Freud Alexander Moritz Frey Erich Fried Egon Friedell Salomon Friedlaender Ernst Friedrich Efraim Frisch Paul Frischauer Eduard Fuchs Louis Fürnberg Ludwig Fulda Peter Gan Manfred George Hellmut von Gerlach Karl Gerold Ernst Glaeser Fjodor Gladkow Georg K. -

Klaus Johann

KLAUS JOHANN Ein hinternationaler Schriftsteller aus Prag Zu Johannes Urzidil und der Wiederentdeckung seines Werkes1 Der Prager deutsche Schriftsteller Johannes Urzidil (1896-1970) wird seit der Wende 1989 in seiner Heimat wiederentdeckt, und auch im deutschsprachigen Raum findet er in den letzten Jahren ein größeres Interesse und wird wieder verstärkt rezipiert. Der Artikel skizziert Leben und Werk dieses bedeutenden böhmischen Autors, weist auf unlängst erschienene Publikationen hin und stellt die geplante Urzidil-Werk- ausgabe vor. 1 Leben und Werk Urzidils Der Sinn [...] aller meiner Bemühungen war immer: Verbindungen herzustellen, Brücken zu schlagen, das Vereinigende zu zeigen und zur Wirkung zu bringen. (Johannes Urzidil 1967: 21) Der bedeutende böhmische Schriftsteller Johannes Urzidil (1896-1970) wurde in Prag als Sohn eines deutschnationalen Ingenieurs und Eisenbahnverwaltungs- beamten und einer tschechisch-jüdischen Mutter geboren, die aus ihrer ersten Ehe bereits sieben Kinder in die zweite mitgebracht hatte. Kurz vor Urzidils viertem Geburtstag starb die Mutter, und der Vater heiratete im Jahre 1903 eine Tschechin, die nicht minder nationalbewusst war als er selbst. Bereits im engsten familiären 1 Der Artikel erschien bereits 2006 unter dem Titel Die Wiederentdeckung eines großen Erzählers aus Prag. Über Johannes Urzidil und eine Neuedition seiner Werke in Modern Austrian Literature (Jg. 39. Nr. 1. S. 85-92); deren Herausgeberin Frau Prof. Dr. Maria-Regina Kecht (Rice University, Houston) sei für die Genehmigung zum Wiederabdruck herzlich gedankt. Für die Aussiger Beiträge wurde der Artikel beträchtlich erweitert und überarbeitet. 79 Aussiger Beiträge 1/2007 Umfeld Urzidils, der von klein auf neben Deutsch auch Tschechisch lernte, sprach und schrieb, spiegelt sich somit in paradigmatischer Weise jene böhmische Gesellschaft wider, die durch Shoa und Zweiten Weltkrieg unwiederbringlich zerstört worden ist. -

Judaica Olomucensia

Judaica Olomucensia 2015/2 Editor-in-Chief Louise Hecht Editor Matej Grochal Table of Content 4 Introduction Louise Hecht 8 Mobility of Jewish Captives between Moravia and the Ottoman Empire in the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century Markéta Pnina Younger 33 Making Paratextual Decisions: On Language Strategies of Moravian Jewish Scribes Lenka Uličná 54 The Beauty of Duty: A new look at Ludwig Winder’s novel Ingeborg Fiala-Fürst 69 The Mapping Wall: Jewish Family Portraits as a Memory Box Dieter J. Hecht 89 Table of Images Judaica Olomucensia 2015/2 – 3 Introduction Louise Hecht The four papers published in this volume are not dedicated to one single topic. They were primarily selected according to scholarly quality. Nevertheless, they are bound together by their relation to Moravia. The focus on Moravian (and eventually also Czech) Jewish studies is a special concern of Judaica Olo- mucensia that distinguishes our journal from other Jewish studies journals in the world. In explicit or implicit ways, there seems to be an additional theme that links the four contributions, namely their connection to migra- tion. Indeed, two of the papers (Markéta Pnina Younger and Dieter J. Hecht) are the result of the international conference “The Land in-Between: Three Centuries of Jewish Migration to, from and across Moravia, 1648–1948”, orga- nized by myself and Michael L. Miller at the Kurt and Ursula Schubert Center for Jewish Studies in November 2012. Obviously, the topic of migration has gained currency in political and social debates in Europe and beyond during the last years. Questions of inte- gration, acculturation, religious (in)compatibility and, especially in Central Europe, linguistic assimilation of the migrant population are in the headlines of all media. -

A General History of Concepts of Exile Centuries)

Introduction A Genera l History of Concepts of Exile Exile is a very complex concept: it is multifaceted and has numerous implications. I have written about it in a personal way1 in the past and I have also taught a class at Indiana University on this topic drawing on the unusually rich and interesting Jewish (predominantly German-language) twentieth-century writing of Central Europe. Ideas developed during these classes have served as a starting point for the present study. Exile has generated wonderful writing since times immemorial— Sappho, Dante, Comenius, Zola, Mann, Joyce, Beckett, Solzhenitsyn, Conrad, to name a few outstanding examples). Twentieth-century European literature, however, plays a special role in the exploration of exile, due to the displacement of vast numbers of people caused by the brutal totalitarian regimes that took over many countries for extended periods of time, the increasing ease of traveling great distances, and technological progress. This study is primarily focused on the variety of meanings that the term “exile” can take on and the different angles from which it can be examined. It is a study that looks at the inner meanings of exile, the types of inner withdrawal due to a lack of acceptance 1 See Bronislava Volková, “Exil vnitřní a vnější,” Listopad (2004): 12–19; “Exile: Inside and Out,” in The Writer Uprooted: Contemporary Jewish Exile Literature, ed. Alvin Rosenfeld (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2008), 161–176; “Psychological, Cultural, Historical and Spiritual Aspects of Exile,” Comenius, Journal of Euro-American Civilisation 1, no. 2 (2014), 199–212; “Exil: psychologický, kulturně-historický, duchovní,” Český Dialog, May 2015, http://www.cesky-dialog.net/clanek/6774-exil- psychologicky-kulturne-historicky-a-duchovni/. -

Bronislava Kuzica Rokytová HANNES BECKMANN (1909–1977)

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE KATOLICKÁ TEOLOGICKÁ FAKULTA Ústav dějin křesťanského umění Dějiny křesťanského umění / Umění 19. a 20. století Bronislava Kuzica Rokytová HANNES BECKMANN (1909–1977) DESAVA – PRAHA – NEW YORK HANNES BECKMANN (1909–1977) DESSAU – PRAGUE – NEW YORK autoreferát disertační práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Marie Rakušanová, PhD. Praha 2017 I. ÚVOD Disertační práce se zabývá životem a dílem umělce Hannese Beckmanna |1909– 1977|. Úděl tohoto malíře, fotografa, scénografa, pedagoga, ale také teoretika zmíněných uměleckých oborů, je spojen s Československem, kde prožil téměř patnáct let. O jeho nejen zdejším působení se toho doposud mnoho nevědělo. Beckmann se narodil 8. října 1909 ve Stuttgartu. V letech 1928 až 1932 studoval na Bauhausu v Desavě u Vasilije Kandinského, Paula Klea nebo Josefa Alberse. Posléze se zaměřil na fotografii, když se stal hospitantem u Waltera Peterhanse, představitele „nové věcnosti”, a následně absolvoval fotografické kurzy ve Vídni. V roce 1934 emigroval z politických důvodů do Československa. Zařadil se tím mezi uprchlíky před nacismem, jejichž život se musel přizpůsobovat proměnlivému diktátu státních úřadů, ovlivňovaných sílícím tlakem sousedního Německa. Jak bude prokázáno, Beckmannova česká léta nebyla zcela typickým intermezzem v životě emigranta. Vzhledem k předchozímu výzkumu věnovanému umělecké emigraci v Československu, je možné úvodem konstatovat, že Hannes Beckmann byl jednou z nepozoruhodnějších osobností, které u nás vedle Oskara Kokoschky, Johna Heartfielda nebo Josefa Jusztusze -

European Charter for Regional Or Minority Languages

Strasbourg, 17 February 2015 MIN-LANG (2014) PR8 Addendum 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Third periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter CZECH REPUBLIC Replies to the comments/questions submitted to the Czech authorities regarding their third periodical report Contents General issues arising from the evaluation of the report .................................................................... 3 Part II ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Part III .................................................................................................................................................... 11 Article 8 - Education ........................................................................................................................... 11 Article 10 - Administrative authorities and public services ................................................................... 11 Article 11 - Media ................................................................................................................................ 12 Article 12 - Cultural activities and facilities .......................................................................................... 13 Article 13 - Economic and social life ................................................................................................... 14 Article 14 - Transfrontier