It Is Perhaps Ironic That a Book About Intercultural Communication Should

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klaus Johann Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3

Klaus Johann Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3. XI. 2010) 1. a.d. (KK): Die siebzehn Reisen Goethes nach Böhmen. [Rezension der erweiterten Neuauflage von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Aufbau (New York). 16. VII. 1982. 2. A.S.: Johannes Urzidil liest. Zimmertheater Heddy Maria Wettstein. In: Die Tat. 17. X. 1970. 3. Abendroth, Friedrich [i.e. Friedrich Weigend-Abendroth] : „Die Erbarmungen Gottes“. [Rezension der Neuausgabe von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Die Furche. Nr. 38. 22. IX. 1962. S.11. 4. Abendroth, Friedrich: Erzählen ist nicht mehr erlaubt? In: Echo der Zeit. 30. X. 1966. 5. Abendroth, Friedrich: Ein böhmisches Buch. [Rezension von Johannes Urzidil, „Die verlorene Geliebte“.] In: Die Furche. Nr.39. 22. IX. 1956. Beilage „Der Krystall“. S.3. 6. Adam, Franz: Mit Franz Kafka saß er im Café. Tagung des Ostdeutschen Kulturrats über Johannes Urzidil. In: Kulturpolitische Korrespondenz. 1037. 5. April 1998. S.11-13. 7. Adler, H. G.: Die Dichtung der Prager Schule. [EA: 1976.] Vorw. v. Jeremy Adler. Wuppertal u. Wien: Arco 2010. ( = Coll’Arco.<FA>3) 8. ag: Ein Dichter Böhmens. Zu einer Vorlesung Johannes Urzidils. In: Stutt- garter Zeitung. 22. XI. 1962. 9. Ahl, Herbert: Ein Historiker seiner Visionen. Johannes Urzidil . In: H.A.: Litera- rische Portraits. München u. Wien: Langen Müller 1962. S.164-172. 10. ak: Vergangenes. [Rezension der Heyne-Taschenbuchausgabe von „Prager Triptychon“.] In: Deutsche Tagespost. 27. VI. 1980. 11. Albers, Heinz: Wie der Freund ihn sah. Johannes Urzidil im Hamburg Cen- trum über Kafka. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. 2. X. 1970. 12. Alexander, Manfred: Einleitung. In: M.A. (Hg.): Deutsche Gesandtschaftsbe- richte aus Prag. -

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: from Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: From Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski La penna è una vanga, scopre fosse, scava e stana scheletri e segreti oppure li copre con palate di parole più pesanti della terra. Affonda nel letame e, a seconda, sistema le spoglie a buio o in piena luce, fra gli applausi generali. The pen is a spade, it exposes graves, digs and reveals skeletons and secrets, or it covers them up with shovelfuls of words heavier than earth. It bores into the dirt and, depending, lays out the remains in darkness or in broad daylight, to general applause. —Claudio Magris, Non luogo a procedere (Blameless) In 1967, Italo Calvino wrote a letter about the “molto interessante e strano” (very interesting and strange) writings of Thomas Bernhard, recommending that the important publishing house Einaudi translate his works (Frost, Verstörung, Amras, and Prosa).1 In 1977, Claudio Magris held one of the !rst international conferences for the Austrian writer in Trieste.2 In 2014, the conference “Il più grande scrittore europeo? Omag- gio a Thomas Bernhard” (The Greatest European Author? Homage to 1 Italo Calvino, Lettere: 1940–1985 (Milan: Mondadori, 2001), 1051. 2 See Luigi Quattrocchi, “Thomas Bernhard in Italia,” Cultura e scuola 26, no. 103 (1987): 48; and Eugenio Bernardi, “Bernhard in Italien,” in Literarisches Kollo- quium Linz 1984: Thomas Bernhard, ed. Alfred Pittertschatscher and Johann Lachinger (Linz: Adalbert Stifter-Institut, 1985), 175–80. Both Quattrocchi and Bernardi -

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, Kritiker und Künstler Antiquariat Frank Albrecht · [email protected] 69198 Schriesheim · Mozartstr. 62 · Tel.: 06203/65713 Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 D Verlag und A Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, S Antiquariat Kritiker und Künstler 2 Frank 0. J A Albrecht H Inhalt R H Belletristik ....................................................................... 1 69198 Schriesheim U Sekundärliteratur ........................................................... 31 Mozartstr. 62 N Kunst ............................................................................. 35 Register ......................................................................... 55 Tel.: 06203/65713 D FAX: 06203/65311 E Email: R [email protected] T USt.-IdNr.: DE 144 468 306 D Steuernr. : 47100/43458 Die Abbildung auf dem Vorderdeckel A zeigt eine Original-Zeichnung von S Joachim Ringelnatz (Katalognr. 113). 2 0. J A H Spezialgebiete: R Autographen und H Widmungsexemplare U Belletristik in Erstausgaben N Illustrierte Bücher D Judaica Kinder- und Jugendbuch E Kulturgeschichte R Unser komplettes Angebot im Internet: Kunst T http://www.antiquariat.com Politik und Zeitgeschichte Russische Avantgarde D Sekundärliteratur und Bibliographien A S Gegründet 1985 2 0. Geschäftsbedingungen J Mitglied im Alle angebotenen Bücher sind grundsätzlich vollständig und, wenn nicht an- P.E.N.International A ders angegeben, in gutem Erhaltungszustand. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro und im Verband H (€) inkl. Mehrwertsteuer. -

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

R:\My Documents\Wordperfect 8 Work Files\Events\2003-2004Programme

INSTITUTE OF GERMANIC STUDIES Programme of Events 2003-2004 The theme of tradition and innovation will feature prominently in the Ingeborg Bachmann Centre’s programme for this year, with a three-day conference on Adalbert Stifter, and workshops on Robert Musil and Joseph Roth, the latter organised in collaboration with the London Jewish Cultural Centre. Evelyn Schlag, one of Austria’s most prolific contemporary writers, will follow Walter Grond and Wolfgang Hermann as the Centre’s writer-in- residence in the spring, her stay coinciding with the publication of a new volume of poetry, whilst the eminent Freud scholar, Peter Gay, is expected to give the first biennial Lecture, details of which will be announced in due course. Established in 2002 at the University of London’s Institute of Germanic Studies, the Centre’s activities continue to be supported by the Erste Bank and the Ingeborg Bachmann Centre Österreich Kooperation. INSTITUTE OF GERMANIC STUDIES Events are open to all who are interested. University of London School of Advanced Study 29 Russell Square Autumn 2003 London WC1B 5DP Telephone: +44 (0)20- 7862 8965/6 Facsimile: +44 (0)20- 7860 8970 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.sas.ac.uk/igs CONFERENCE Wednesday, 10 to WORKSHOP Thursday, 10 June 2004 Friday, 12 December 2003 Stifter and Modernism Joseph Roth - Revisited or Reinvented? The Reception of Roth’s Works in Britain As a proponent of a specific aesthetic and moral order, Adalbert Stifter has long been regarded as a natural heir to the Great Classical Tradition. Yet Critics claim, and an increasing number of new readers testify, that the even critics persuaded of this view have often detected troubling sub-texts works of Joseph Roth are currently enjoying a remarkable renaissance, within his fiction. -

Die Autoren Und Herausgeber

363 Die Autoren und Herausgeber Anke Bosse (1961) studierte Germanistik, Romanistik und Kompa- ratistik in Göttingen und München. Seit 1997 Universitätsdozentin für Germanistik und Komparatistik an der Universität Namur (Belgien) und Direktorin des dortigen Instituts für Germanistik. Publikationen (Auswahl): „Meine Schatzkammer füllt sich täglich …“ – Die Nachlaßstücke zu Goethes ‚West-östlichem Divan‘. Dokumentation. Kommentar. Entstehungsgeschichte. 2 Bde. (1999); „Eine geheime Schrift aus diesem Splitterwerk enträtseln …“ Marlen Haushofers Werk im Kontext. (Mithg., 2000); Spuren, Signaturen, Spiegelungen. Zur Goethe-Rezeption in Europa. (Mithg., 2000). Forschungs- schwerpunkte: Theorie und Praxis der Edition, Textge-nese und Schreibprozesse, deutschsprachige Literatur des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts (speziell Goethe), deutschsprachige Gegenwartsliteratur, literarische Moderne um 1900, Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Literatur, Orientalismus und Interkulturalität, Apokalypse in der Literatur, Literaturdidaktik. Anschrift: Universität Namur, Direktorin des Instituts für Germanistik, Rue de Bruxelles 61, B-5000 Namur. E- Mail: [email protected] Leopold R.G. Decloedt (1964) studierte Germanistik und Nieder- landistik an der Universität Gent. 1992 Promotion zum Dr. phil. Mitherausgeber der Reihe “Wechselwirkungen. Österreichische Litera-tur im internationalen Kontext” (Bern: Peter Lang). 1994-1999: Leiter der Abteilung Niederländisch an der Masaryková Univerzita in Brno. Zur Zeit Lehrbeauftragter am Institut für Germanistik der Universität -

München Liest

Die verbrannten Dichter: „Die Waffen nieder!“ (Bertha von Suttner) Nathan Asch - Martin Andersen-Nexö - Ernst Barlach - Oskar Baum - Vicki Baum - Johannes R. Becher - Walter Benjamin - Martin Beradt - Eduard Bernstein - Franz Blei - Bertolt Brecht - Willi Bredel - Joseph Breitbach - Max Brod - Ferdinand Bruckner - Elias Canetti - Veza Canetti - Elisabeth Castonier - Franz Th. Csokor - Alfred Döblin - John Dos Passos - Kasimir Edschmid - Hans Fallada - Lion Feuchtwanger - Marieluise Fleißer - Bruno Frank - Leonhard Frank - Anna Freud - Sigmund Freud - Egon Friedell - Richard Friedenthal -Claire Goll - Maxim Gorki - Oskar Maria Graf - Karl Grünberg - Willy Haas - Hans Habe - Jakob Haringer - Walter Wenn Sie fünf Minuten aus einem Hasenclever - Georg Hermann - Franz Hessel - “verbrannten Buch” vorlesen möchten, Ödön von Horvath - Oskar Jellinek - Erich Kästner - rufen Sie bitte an unter Franz Kafka - Mascha Kaleko - Gina Kaus - Hermann 089 - 157 32 19. Kesten - Irmgard Keun - Egon Erwin Kisch - Klabund - Annette Kolb - Gertrud Kolmar - Paul Kornfeld - Theodor Kramer - Else Lasker-Schüler - Maria Veranstalter: Leitner - Theodor Lessing - Jack London - Emil - Institut für Kunst und Forschung, München, Ludwig - Heinrich Mann - Klaus Mann - Thomas Wolfram P. Kastner, Tel. 089 - 157 32 19 Mann - Valeriu Marcu - Walter Mehring - Konrad Merz - Max Mohr - Erich Mühsam - Hans Natonek - Mitveranstalter: - Landeshauptstadt München, Max Hermann Neiße - Alfred Neumann - Robert Kulturreferat und Referat fur Bildung und Sport Neumann - Leo Perutz - Carl -

Walt Whitman

CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN WALT WHITMAN CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN Walt Whitman BY WALTER GRUNZWEIG UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS 1!11 IOWA CITY University oflowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 1995 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gri.inzweig, Walter. Constructing the German Walt Whitman I by Walter Gri.inzweig. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87745-481-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-87745-482-5 (paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892-Appreciation-Europe, German-speaking. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892- Criticism and interpretation-History. 3. Criticism Europe, German-speaking-History. I. Title. PS3238.G78 1994 94-30024 8n' .3-dc2o CIP 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 c 5 4 3 2 1 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 p 5 4 3 2 1 To my brother WERNER, another Whitmanite CONTENTS Acknowledgments, ix Abbreviations, xi Introduction, 1 TRANSLATIONS 1. Ferdinand Freiligrath, Adolf Strodtmann, and Ernst Otto Hopp, 11 2. Karl Knortz and Thomas William Rolleston, 20 3· Johannes Schlaf, 32 4· Karl Federn and Wilhelm Scholermann, 43 5· Franz Blei, 50 6. Gustav Landauer, 52 7· Max Hayek, 57 8. Hans Reisiger, 63 9. Translations after World War II, 69 CREATIVE RECEPTION 10. Whitman in German Literature, 77 11. -

Benjamin (Reflections).Pdf

EFLECTIOMS WALTEU BEHiAMIH _ Essays, Aphorisms, p Autobiographical Writings |k Edited and with an Introduction by p P e t e r D e m e t z SiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiittiiiiiiiiiiiiiltiAMiiiiiiiAiiiiiiiiii ^%lter Benjamin Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical W ritings Translated, by Edmund Jephcott Schocken Books^ New York English translation copyright © 1978 by Harcourt BraceJovanovich, Inc. Alt rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conven tions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New YoTk. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. These essays have all been published in Germany. ‘A Berlin Chronicle” was published as B erliner Chronik, copyright © 1970 by Suhrkamp Verlag; "One-Way Street” as Einbahnstrasse copyright 1955 by Suhrkamp Verlag; "Moscow,” “Marseilles;’ “Hashish in Marseilles:’ and " Naples” as “Moskau “Marseille,” “Haschisch in Marseille,” and “Weapel” in Gesammelte Schrifen, Band IV-1, copyright © 1972 by Suhrkamp Verlag; “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century," “Karl Kraus,” - and "The Destructive Character” as "Paris, die H auptskult des XlX.Jahrhvmdertsl' "Karl Kmus’,’ and “Der destruktive Charakter" in llluminationen, copyright 1955 by Suhrkamp Verlag; “Surrealism,” “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man,” and “On the M i me tic faculty" as “Der Silry:eaWsmus,” “Uber die Sprache ilberhaupt und ilber die Sprache des Menschen” and "Uber das mimelische Vermogen” in Angelus copyright © 1966 by Suhrkamp Verlag; “ Brecht’s Th r eep en n y Novel” as “B r e c h t ’s Dreigroschmroman" in Gesammelte Sr.hrifen, Band III, copyright © 1972 by Suhrkamp Verlag; “Conversations with Brecht” and “The Author as Producer" as “Gespriiche mit Brecht" and “Der Autor ais Produz.erit” in Ver-SMche ilber Brecht, copyright © 1966 by Suhrkamp Verlag; “Critique of Violence/' "Fate and Character,” and “Theologico-Political Fragment” as "Zur K r itiz der Gewalt',' "Schicksal und Charakter" and "Theologisch-polilisches Fr< ^ m ent" in Schrifen, Band I, copyright © 1955 by Suhrkamp Verlag. -

Franz Werfel Papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt800007v5 No online items Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 Finding aid prepared by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 15 December 2017. Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 1 LSC.0512 Title: Franz Werfel papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0512 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 18.5 linear feet(37 boxes and 1 oversize box) Date: 1910-1944 Abstract: Franz Werfel (1890-1945) was one of the founders of the expressionist movement in German literature. In 1940, he fled the Nazis and settled in the U.S. He wrote one of his most popular novels, Song of Bernadette, in 1941. The collection consists of materials found in Werfel's study at the time of his death. Includes correspondence, manuscripts, clippings and printed materials, pictures, artifacts, periodicals, and books. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the request button located on this page. Werfel's desk on permanent loan to the Villa Aurora in Pacific Palisades. Creator: Werfel, Franz, 1890-1945 Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Painting, Writing, and Human Community in Adalbert Stifter's

UCLA New German Review: A Journal of Germanic Studies Title Intersecting at the Real: Painting, Writing, and Human Community in Adalbert Stifter’s Nachkommenschaften (1864) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6225t5wf Journal New German Review: A Journal of Germanic Studies, 27(1) ISSN 0889-0145 Author Bowen-Wefuan, Bethany Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Intersecting at the Real: Painting, Writing, and Human Community in Adalbert Stifter’s Nachkommenschaften (1864) Bethany Bowen-Wefuan In Adalbert Stifter’s novella Nachkommenschaften (Descendants; 1864), the protagonist Friedrich Roderer struggles to represent the essence of natural land- scapes—what he, as the narrator, calls the “wirkliche Wirklichkeit” (40) and what I refer to as the Real—in his roles as a landscape painter and writer. Through Friedrich, Stifter explores the very notion of realism. John Lyon describes the aims of realism thus: “Realism must […] convey an ideal, a sense of truth present in external reality, but not evident to the untrained eye […]. The realist perceives the ideal and lets it shine through” (16). For the realist Friedrich, the challenge of representing the “truth present in external reality” in both painting and writing lies in the complex relationship between his own subjective interpretation of physical reality and the aesthetic conventions that history and culture have handed him. Like a pendulum, he sways between embracing subjectivity and rejecting conven- tion. Furthermore, while he initially searches for the Real in representation, he later pursues it in domestic life. In each extreme, the Real eludes him. It can neither be relegated to a particular convention nor to subjective interpretations of the physi- cal world. -

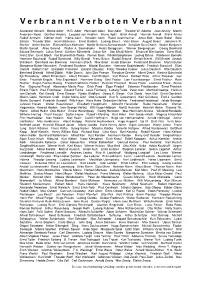

V E R B R a N N T V E R B O T E N V E R B a N

V e r b r a n n t V e r b o t e n V e r b a n n t Alexander Abusch Bruno Adler H.G. Adler Hermann Adler Max Adler Theodor W. Adorno Jean Améry Martin Andersen Nexö Günther Anders Leopold von Andrian Bruno Apitz Erich Arendt Hannah Arendt Frank Arnau Rudolf Arnheim Nathan Asch Käthe Asch Schalom Asch Raoul Auernheimer Julius Bab Isaak Babel Béla Balázs Theodor Balk Henri Barbusse Ernst Barlach Ludwig Bauer Vicki Baum August Bebel Johannes R. Becher Ulrich Becher Richard Beer-Hofmann Martin Beheim-Schwarzbach Schalom Ben-Chorin Walter Benjamin Martin Beradt Alice Berend Walter A. Berendsohn Heinz Berggruen Werner Bergengruen Georg Bernhard Eduard Bernstein Julius Berstl Günther Birkenfeld Oskar Bie Oto Bihalji-Merin Emanuel Bin-Gorion Ernst Blaß Franz Blei Ernst Bloch Ilse Blumenthal-Weiss Werner Bock Nikolai Bogdanow Ludwig Börne Waldemar Bonsels Hermann Borchardt Rudolf Borchardt Willy Brandt Franz Braun Rudolf Braune Bertolt Brecht Willi Bredel Joseph Breitbach Bernhard von Brentano Hermann Broch Max Brod Arnolt Bronnen Ferdinand Bruckner Martin Buber Margarete Buber-Neumann Ferdinand Bruckner Nikolai Bucharin Hermann Budzislawski Friedrich Burschell Elias Canetti Robert Carr Elisabeth Castonier Eduard Claudius Franz Theodor Csokor Julius Deutsch Otto Deutsch Bernhard Diebold Alfred Döblin Hilde Domin John Dos Passos Theodore Dreiser Albert Drach Kasimir Edschmid Ilja Ehrenburg Albert Ehrenstein Albert Einstein Carl Einstein Kurt Eisner Norbert Elias Arthur Eloesser Lex Ende Friedrich Engels Fritz Erpenbeck Hermann Essig Emil Faktor Lion Feuchtwanger Ernst Fischer Ruth Fischer Eugen Fischer-Baling Friedrich-Wilhelm Förster Heinrich Fraenkel Bruno Frank Leonhard Frank Bruno Frei Sigmund Freud Alexander Moritz Frey Erich Fried Egon Friedell Salomon Friedlaender Ernst Friedrich Efraim Frisch Paul Frischauer Eduard Fuchs Louis Fürnberg Ludwig Fulda Peter Gan Manfred George Hellmut von Gerlach Karl Gerold Ernst Glaeser Fjodor Gladkow Georg K.