Judaica Olomucensia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gemilut Chasadim Project Instructions, Texts, and Assignments

Mount Zion B’nei Mitzvah Gemilut Chasadim Project Instructions, Texts, and Assignments ִשׁ ְמעוֹן ַה ַצּ ִדּיק ָה ָיה ִמ ְשּׁ ָי ֵרי ְכ ֶנ ֶסת ַה ְגּדוֹ ָלה. הוּא ָה ָיה אוֹ ֵמר, ַעל ְשׁל ָשׁה ְד ָב ִרים ָהעוֹ ָלם עוֹ ֵמד, ַעל ַהתּוֹ ָרה ְו ַעל ָה ֲעבוֹ ָדה ְו ַעל ְגּ ִמילוּת ֲח ָס ִדים: Shimon the Righteous was one of the last of the great assembly. He used to say: the world stands upon three things: Torah, Avodah, and Gemilut Chasadim Pirkei Avot (Ethics of our Ancestors – from the Talmud) 1:2 Keeping the Mitzvah in B’nei Mitzvah: th 7 Grade Mitzvah Exploration and Project Page 1 Content created by Sam Schauvaney, Rabbinic Intern, Mount Zion – Summer 2019. Questions? Contact: Sue Summit, Religious School Director [email protected] 651-698-3881 Big Picture Part 1: What is a Mitzvah? ............................................................................ 4 Big Picture Part 2: The Three Pillars .............................................................................. 5 Torah, Avodah, Gemilut Chasadim ............................................................................ 5 What is a Gemilut Chasadim Project? ............................................................................ 6 Requirements: To help you reflect and find meaning in your work, you will: ......................................... 6 th Important Dates of the 7 grade year ..................................................................................................... 6 Gemilut Chasadim Project Journal Entry Form #1 ............................................................... -

Ottoman Empire & European Theatre VIII

Ottoman Empire & European Theatre VIII ______________ 28 – 29 M a y 2 0 1 5 International Symposium I s t a n b u l – Pera Museum Culture, Diplomacy and Peacemaking: Ottoman-European Relations in the Wake of the Treaty of Belgrade (1739) and the Era of Maria Theresia (r.1740–1780) Under the patronage of Exc. Hasan Göğüş Exc. Dr. Klaus Wölfer Ambassador of & Ambassador of the Republic of Turkey in Vienna the Republic of Austria in Ankara In cooperation with International Symposium Istanbul 2015 by Don Juan Archiv Wien OTTOMAN EMPIRE & EUROPEAN THEATRE VIII Culture, Diplomacy and Peacemaking: Ottoman-European Relations in the Wake of the Treaty of Belgrade (1739) and the Era of Maria Theresia (r.1740–1780) 28 – 29 May 2015 Istanbul, Pera Museum Organized by Don Juan Archiv Wien In cooperation with Pera Museum Istanbul, The UNESCO International Theatre Institute in Vienna (ITI) and The Austrian Cultural Forum in Istanbul PROGRAMME OVERVIEW Thursday, May 28th 2015 10:00–11:00 Opening Ceremony 11:00–11:30 Coffee Break 11:30–12:45 Session I “Of Ottoman Diplomacy” Seyfi Kenan The Education of an Ottoman Envoy during the Early Modern Period (Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries) John Whitehead The Embassy of Yirmisekizzade Said Mehmed Pasha to Paris (1742) 12:45–14:00 Lunch Break 14:00–15:15 Session II “The Siege of Belgrade (1789) and the Legend of a Field Marshal” Tatjana Marković Celebrating Field Marshal Gideon Ernest von Laudon (1717–1790) in European Literature and Music Michael Hüttler Celebrating Field Marshal Gideon Ernest von Laudon (1717–1790) in Theatre: The Siege of Belgrade on Stage 15:15–15:30 Coffee Break 15:30–16:45 Session III “Theatrical Aspects: Venice, Paris” Maria Alberti L’impresario delle Smirne (‘The Impresario from Smyrna’, 1759) by Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793), Namely the Naive Turk Aliye F. -

Klaus Johann Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3

Klaus Johann Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3. XI. 2010) 1. a.d. (KK): Die siebzehn Reisen Goethes nach Böhmen. [Rezension der erweiterten Neuauflage von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Aufbau (New York). 16. VII. 1982. 2. A.S.: Johannes Urzidil liest. Zimmertheater Heddy Maria Wettstein. In: Die Tat. 17. X. 1970. 3. Abendroth, Friedrich [i.e. Friedrich Weigend-Abendroth] : „Die Erbarmungen Gottes“. [Rezension der Neuausgabe von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Die Furche. Nr. 38. 22. IX. 1962. S.11. 4. Abendroth, Friedrich: Erzählen ist nicht mehr erlaubt? In: Echo der Zeit. 30. X. 1966. 5. Abendroth, Friedrich: Ein böhmisches Buch. [Rezension von Johannes Urzidil, „Die verlorene Geliebte“.] In: Die Furche. Nr.39. 22. IX. 1956. Beilage „Der Krystall“. S.3. 6. Adam, Franz: Mit Franz Kafka saß er im Café. Tagung des Ostdeutschen Kulturrats über Johannes Urzidil. In: Kulturpolitische Korrespondenz. 1037. 5. April 1998. S.11-13. 7. Adler, H. G.: Die Dichtung der Prager Schule. [EA: 1976.] Vorw. v. Jeremy Adler. Wuppertal u. Wien: Arco 2010. ( = Coll’Arco.<FA>3) 8. ag: Ein Dichter Böhmens. Zu einer Vorlesung Johannes Urzidils. In: Stutt- garter Zeitung. 22. XI. 1962. 9. Ahl, Herbert: Ein Historiker seiner Visionen. Johannes Urzidil . In: H.A.: Litera- rische Portraits. München u. Wien: Langen Müller 1962. S.164-172. 10. ak: Vergangenes. [Rezension der Heyne-Taschenbuchausgabe von „Prager Triptychon“.] In: Deutsche Tagespost. 27. VI. 1980. 11. Albers, Heinz: Wie der Freund ihn sah. Johannes Urzidil im Hamburg Cen- trum über Kafka. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. 2. X. 1970. 12. Alexander, Manfred: Einleitung. In: M.A. (Hg.): Deutsche Gesandtschaftsbe- richte aus Prag. -

JO2000-V33-N05.Pdf

1111r~~S[~1Jo£i1'e~~ .~(si~E~'*''!i!; ~~~Tl, , i~~1!~li~~N1~~!~G. ll;S~O~& CAMP i (,•< l .. jA$K~JB~ll & VO . :::{:;,~&<; f "'!!~,"!~ : •.. ' ~\.. s ii;•i } ... • i •, Ill fl@BBE~;'RESll.IENJ:fllO.ORlkG • ;:,· 1111 1i1c~·i; ,, ~ .t ~~i~~~~ meetit·o~;e~ce~.d~i ~11;'1'~;\'~ and. CP~CJ'~e,, ;\, qui~~I·~~ ... ... '' '• ~; ;j i ~·· Sit~·;p(~n~ing,and•d~s~n);: . sewites with state~oHthe#ad A ·'~1~1< "··~;;li;m~6~' ~W:o..n{Hlff, .. D .• ••··· REl:REATIO~~ D~al, ·,., 4: 1wiJl;;!l'A~s- s. Falf;b~.tg, ·.·~~··· W~l!llN HOUSE~ ••Brqwn~t:!f:le, NY. HA.Sp;~.>Canarsie,.fNX ....... 'J' YES~lv~ DERECH'1ES '•MoJl*~y, NY YE .. .. DARClfEFTQ~A~; - t?',!; · , .··.. ,,;;;;Far Bpc~~W,ay, NY J9~A~~1~t~ -'~!~~' • ;:i , s~r1~0 ~~t!~Y.N'('. .. ·... IM1V,IS~NIJl •ipo1;@;•1N:ark' ·' · · ft:. AW~E~lDEN&~ -•;Deal, NJ · PA~KEASTOAY~~HOQL- New York, NY ESSEXGENERAl' ~taten Island, NY .. RebbesaNd Cboss1d11n: WIXlt: t:hey SOJd - what: t:he memtt: Sf TE Thursday, June 15 thru Monday, June 26, 2000 hat'.s NEW on the Feldheim menu r£Information .r£l1JJpiration r£Good Healtb an:d r£Great Rea'Qillfl f Jerusalem: Footsteps Ethics From Sinai A Wide-ranging Commentary on Pirkei Avos Through Time By Irving M. Bunim 10 Torah Study Tours of the Old City ince it first appeared, nearly 40 years ago, Irving Bunim's ETHICS FROM SINAI has §become a perennial favorite among readers he full scope everywhere. With its tremendous scope of com of Jewish mentary, written with warmth, wit, and wisdom, l history and full of Irving Bunim's indomitable spirit, this comes vividly to text has become a contemporary classic - and life in this fasci deservedly so! nating and enchanting guide Now, we are is pleased to present a beautiful, newly through the Old designed and completely revised edition of this popular work. -

Democracy and European Emerging Values: the Right to Decide

DEMOCRACY AND EUROPEAN EMERGING VALUES: THE RIGHT TO DECIDE COORDINATED BY GERARD BONA LANGUAGE REVIEW BY EMYR GRUFFYDD CENTRE MAURITS COPPIETERS 2015 Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 8 LAKE OR RIVER 14 THE POLITICAL CARTOONING OF CORNISH SELF-DETERMINATION 22 SELF-DETERMINATION AND WALES 44 TOWARDS SOVEREIGN FAROE ISLANDS 54 ABOUT TRANSYLVANIA 62 THE UDBYOUTH : HOW TO BE YOUNG, BRETON AND LEFT-WING WITHOUT AUTONOMY? 72 THE AUTONOMY GENERATION 80 SELF-DETERMINATION AND THE SILESIAN ISSUE 84 THE VALENCIAN COUNTRY AND THE RIGHT OF SELF-DETERMINATION 96 LIBERTY FOR BAVARIA 106 SOVEREIGNTY TO BUILD A GALIZA WITH THE PROMISE OF WORK AND A FUTURE FOR OUR YOUNG PEOPLE 112 “UNTIL ECONOMIC POWER IS IN THE HANDS OF THE PEOPLE, THEN THEIR CULTURE, GAELIC OR ENGLISH, WILL BE DESTROYED” 124 FLANDERS: ON THE ROAD TO BELGIAN STATE REFORM NUMBER 7 132 THE RIGHT OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN THE CATALAN COUNTRIES: 146 THE RIGHT TO DECIDE OF THREE COUNTRIES AND THEIR NATION This publication is financed with the support of the European Parliament (EP). THE MORAVIAN RIGHT TO SELF-DETERMINATION 154 The EP is not responsible for any use made of the content of this publication. The editor of the publication is the sole person liable. THE ROLE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN THE SELF-DETERMINATION PROCESS OF ARTSAKH 164 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. THE YOUTH, PIONEERS IN THE SELF-DETERMINATION OF SOUTH TYROL? 178 This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information CENTRE MAURITS COPPIETERS 188 contained therein. -

Twenty Payment Life Policy the MASSACHUSETTS

II ADVERTISEMENTS A SAFE INVESTMENT FOR YOU Did you ever try to invest money safely? Experienced Financiers find this difficult: How much more so an inexperienced person. ...THE... Twenty Payment Life Policy (With its Combined Insurance and Endowment Features) ISSUED By THE MASSACHUSETTS MUTUAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, OF SPRINGFIELD, MASS. is recommended to you as an investment, safe and profitable. The Policy is plain and simple and the privileges and values are stnted in plain figures that any one can read. It is a sure and systematic way of saving money for your own use or support in later years. Saving is largely a matter of habit. And the semi-compulsory feature cultivates that saving habit. Undir the contracts issued by the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insur- ance Company the protection afforded is unsurpassed. For further information address HOME OFFICE, Springfield, Mass., or New York Office, Empire Building, 71 Broadway. PHILADELPHIA OFFICE, - - - Philadelphia Bourse. BALTIMORE " 4 South Street. CINCINNATI " - Johnston Building. CHICAGO " Merchants Loan and Trust Building. ST. LOUIS " .... Century Building. ADVERTISEMENTS III 1851, 1901. The Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company, of Hartford, Connecticut, Issues Endowment Policies to either men or women, which (besides.giving Five other options) GUARANTEE when the Insured is Fifty, Sixty, or Seventy Years Old To Pay $1,500 in Cash for Every $1,000 of Insurance in force. Sample Policies, rates, and other information will be given on application to the Home Office. ¥ ¥ ¥ JONATHAN B. BUNCE, President. JOHN M. HOLCOMBE, Vice-President. CHARLES H. LAWRENCE, Secretary. MANAGERS: WEED & KENNEDY, New York. JULES GIRARDIN, Chicago. H. W. -

Making a Statement

Making an Impact YOUR STATEMENT QUARTER 2: 2014/2015 We wanted to introduce you to two creative programs funded by the United Jewish Endowment Fund, in partnership with donors, that are making meaningful impacts in our community. Making a Statement PJ LIBRARY JEWISH FOOD EXPERIENCE A free monthly book club A program using food to connect for families with children ages 0-8 people to Jewish life Message from the President TABLE OF CONTENTS and Managing Director Pidyon Shvuyim—redeeming the captive—is among the most important of Jewish commandments. In fact, Maimonides declared that the redeeming of captives even takes 1 precedence over supporting the poor or clothing them. WELCOME In December, the staff of The Jewish Federation of Greater Washington had the opportunity to welcome home Alan Gross. Alan, as was so well publicized, was held captive in Cuba for five years. Alan came to The Jewish Federation of Greater Washington and the Jewish 2 Community Relations Council to articulate his gratitude to our Community for its efforts to INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO secure his release. His jovial and heartfelt words of thanks were well received and he would SUMMARY like his sentiments to be communicated to you. (Coincidentally, Alan’s release was timed almost identically with our reading of the story of Joseph in the bible and his unjust incarceration both at the hands of his brothers and by When parents read a PJ Library book to children before bed, they share their Volunteers cook to combat hunger at N Street Village, one of many programs 3 Pharaoh.) love of reading, nurture an early connection to Jewish values, and teach supported by the Jewish Food Experience offering volunteers an opportunity COFFEE TALK: valuable lessons of holidays and tradition while planting an important seed to come together to chop, cook and prepare food to be donated to DC Pidyon Shvuyim is yet another example of Judaism extolling us to exercise consideration families in need. -

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, Kritiker und Künstler Antiquariat Frank Albrecht · [email protected] 69198 Schriesheim · Mozartstr. 62 · Tel.: 06203/65713 Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 D Verlag und A Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, S Antiquariat Kritiker und Künstler 2 Frank 0. J A Albrecht H Inhalt R H Belletristik ....................................................................... 1 69198 Schriesheim U Sekundärliteratur ........................................................... 31 Mozartstr. 62 N Kunst ............................................................................. 35 Register ......................................................................... 55 Tel.: 06203/65713 D FAX: 06203/65311 E Email: R [email protected] T USt.-IdNr.: DE 144 468 306 D Steuernr. : 47100/43458 Die Abbildung auf dem Vorderdeckel A zeigt eine Original-Zeichnung von S Joachim Ringelnatz (Katalognr. 113). 2 0. J A H Spezialgebiete: R Autographen und H Widmungsexemplare U Belletristik in Erstausgaben N Illustrierte Bücher D Judaica Kinder- und Jugendbuch E Kulturgeschichte R Unser komplettes Angebot im Internet: Kunst T http://www.antiquariat.com Politik und Zeitgeschichte Russische Avantgarde D Sekundärliteratur und Bibliographien A S Gegründet 1985 2 0. Geschäftsbedingungen J Mitglied im Alle angebotenen Bücher sind grundsätzlich vollständig und, wenn nicht an- P.E.N.International A ders angegeben, in gutem Erhaltungszustand. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro und im Verband H (€) inkl. Mehrwertsteuer. -

The Siege of Belgrade on Stage

Michael Hüttler THEATRE AND CULTURAL MEMORY: THE SIEGE OF BELGRADE ON STAGE Michael Hüttler (Vienna) Abstract: This contribution considers the historical image of Belgrade created by European playwrights and librettists of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Istanbul has been for a long time the symbol of an oriental city and lifestyle in the Western European mind – an image that was transmitted especially in poetry and dramatic texts. Belgrade seems to be present in a different way in the European cultural memory. Analysis of the representation of history related to Belgrade in the medium of theatre is based on the four selected historical theatre texts: Hannah Brand’s Huniades, or The Siege of Belgrade (Norwich, 1791/1798); Carl Kisfaludy’s Ilka oder die Einnahme von Griechisch-Weissenburg (Pest, 1814); James Cobb’s The Siege of Belgrade (London 1791/1828); und Friedrich Kaiser’s General Laudon (Vienna, 1875). In this article I would like to investigate the historical image of Belgrade created by European playwrights and librettists of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. What are the contents transported in the dramatic texts about Belgrade? Is a certain historical-political context present, which dominates the entertainment factor? Istanbul has been for a long time the symbol of an oriental city and lifestyle in the Western European mind – an image that was transmitted especially in poetry and dramatic texts. Belgrade seems to be present in a different way in the European cultural memory. In his 1963 essay Sur Racine (‘On Racine’) Roland Barthes already posed the question of how to deal academically with the challenge of the relation between history and a work of art, be it music or a dramatic text. -

Conquering the Conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480

Conquering the conqueror at Belgrade (1456) and Rhodes (1480): irregular soldiers for an uncommon defense Autor(es): De Vries, Kelly Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41538 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_13 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 13:38:47 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kelly DeVries Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) CONQUERING THE CONQUEROR AT BELGRADE (1456) AND RHODES (1480): IRREGULAR SOLDIERS FOR AN UNCOMMON DEFENSE(1) Describing Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II's military goals in the mid- -fifteenth century, contemporary Ibn Kemal writes: "Like the world-illuminating sun he succumbed to the desire for world conquest and it was his plan to burn with overpowering fire the agricultural lands of the rebellious rulers who were in the provinces of the land of Rüm [the Byzantine Empire!. -

Jews and the Language of Eastern Slavs

Jews and the Language of Eastern Slavs Alexander Kulik Jewish Quarterly Review, Volume 104, Number 1, Winter 2014, pp. 105-143 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jqr/summary/v104/104.1.kulik.html Access provided by Hebrew University of Jerusalem (16 Feb 2014 01:30 GMT) T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 104, No. 1 (Winter 2014) 105–143 Jews and the Language of Eastern Slavs ALEXANDER KULIK INTRODUCTION THE BEGINNINGS OF JEWISH PRESENCE in Eastern Europe are among the most enigmatic and underexplored pages in the history of the region. The dating and localization of Jewish presence, as well as the origin and cultural characteristics of the Jewish population residing among the Slavs in the Middle Ages, are among the issues which have become a subject of tense discussion and widely diverging evaluations, often connected to extra-academic ideological agendas. The question of the spoken language of the Jews inhabiting Slavic lands during the Mid- dle Ages is unresolved. Did all or most of these Jews speak languages of their former lands (such as German, Turkic, or Greek), did they speak local Slavic vernaculars? Or did they, perhaps, speak some Judeo-Slavic vernacular(s), which later became extinct? If the last two suggestions appear plausible, then was the Jews’ experience limited to oral usage, or can we also expect to find written evidence of Slavic literacy among medieval Jews? What impact could such literacy on the part of the Jews have had on the literary production and intellectual horizons of Slavs? Or could it even have impacted East Slavic cultural contacts with Latin Europe, in which Slavic-literate Jews may have been involved? The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) / ERC grant agreement no 263293. -

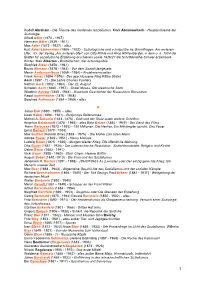

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935)