Rural Net Zero the Role of Rural Local Authorities in Reaching Net Zero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town-Parish-Candidates-Guidance

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT FOR PROSPECTIVE TOWN & PARISH COUNCIL CANDIDATES May 2021 Town and Parish Council Elections www.shropshire.gov.uk Follow us on Twitter: @ShropCouncil MARCH 2021 MESSAGE FROM CLAIRE PORTER THE RETURNING OFFICER Elections are taking place on Thursday 6 May for both the town/parish and unitary tiers of local government, and those candidates who are successfully elected will take up office for a period of four years. The Police and Crime Commissioner Election for the West Mercia Police Area, which was postponed from May 2020, will also take place on the same day. I am the Returning Officer for all town and parish council elections and unitary elections being held within Shropshire Council’s area. Due to the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic, this election will be like no other, and has provided my Elections Team with a whole new set of challenges to make sure that candidates, the electorate and those working at both polling stations and the counting of votes, will all feel safe throughout the electoral process, whilst working to maintain the usual high standards of service provided at all elections. My Team has provided extra guidance on items which have been affected by Covid-19 as part of this pack, but should you have any other queries on our Coronavirus arrangements or any other topic during the election period, please contact a member of my Team (preferably by email), who will endeavour to help you with any queries you may have – [email protected]. I hope that this guidance document will hopefully answer many of your initial queries. -

Standards Exchange Website Extracts , Item 4. PDF 77 KB

STANDARDS ISSUES ARISEN FROM OTHER PARTS OF THE COUNTRY Cornwall Council A Cornwall councillor who said disabled children “should be put down” has been found guilty of breaching the councillors’ code of conduct – but cannot be suspended. Wadebridge East member Collin Brewer’s comments were described by a panel investigating the claims as “outrageous and grossly offensive”. Cornwall Council said it received 180 complaints about Mr Brewer following the revelation that he said disabled children should be put down as they cost the council too much – and a subsequent interview he gave to the Disability News Service after his re-election on May 2 where he likened disabled children to deformed lambs. On Friday its findings were considered by the council’s standards committee in a behind-closed-doors session. Although Mr Brewer has been found to be in breach of the Code of Conduct, the council does not have the legal power to remove him from his position as a councillor. A council spokesman said: “The authority previously had the ability to suspend councillors following the investigation and determination of Code of Conduct complaints, however, following the Government’s changes to the Code of Conduct complaints process, this sanction is no longer available.” The council said that “given the seriousness of the breach” the council’s monitoring has imposed the highest level of sanctions currently available to the council. These include: • Formally censuring Mr Brewer for the outrageous and grossly insensitive remarks he made in the telephone conversation with John Pring on May 8 and directing him to make a formal apology for the gross offensiveness of his comments and the significant distress they caused. -

Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report And Statement of Accounts Information Classification: CONTROLLED This page is intentionally blank Information Classification: CONTROLLED Contents Cornwall Council 2018/19 Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts Contents Page Narrative Report 2 Independent Auditor’s Report for Cornwall Council 25 Independent Auditor’s Report for Cornwall Pension Fund 31 Statement of Accounts Statement of Responsibilities and Certification of the Statement of Accounts 35 Main Financial Statements 37 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 38 Movement in Reserves Statement 38 Balance Sheet 40 Cash Flow Statement 40 Notes to the Main Financial Statements 42 Index of Notes 43 Group Financial Statements 123 Group Movement in Reserves Statement 124 Group Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement 124 Group Balance Sheet 126 Group Cash Flow Statement 126 Notes to the Group Financial Statements 128 Supplementary Financial Statements 139 Housing Revenue Account 141 Notes to the Housing Revenue Account 143 Collection Fund 149 Notes to the Collection Fund 151 Fire Fighters’ Pension Fund Account 153 Pension Fund Accounts 157 Cornwall Local Government Pension Scheme Accounts 158 Notes to the Pension Scheme Accounts 159 Glossary 189 Page 1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED Narrative Report Cornwall Council 2018/19 Statement of Accounts Narrative Report from Chief Operating Officer and Section 151 Officer I am pleased to introduce our Annual Financial Report and Statement of Accounts for 2018/19. This document provides a summary of Cornwall Council’s financial affairs for the financial year 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 and of our financial position at 31 March 2019. -

Shropshire Economic Profile

Shropshire Economic Profile Information, Intelligence and Insight, Shropshire Council January 2017 Table of Contents Key Characteristics 1 Context 2-7 Location 2 Deprivation 2-3 Travelling to Work 4-5 Commuting Patterns 5-6 Self -Containment 6-7 Demographics 8-9 Labour Force, Employment and Unemployment 10 -18 Economic Activity 10 -14 Economic Inactivity 14 Employment 15 Unemployment 16 Benefit Claimants 16 -18 Skills and Occupations 19 -21 Skills 19 -20 Occupations 21 Earnings 22 -23 Shropshire Business Base 24 -37 Business and Employment 24 -25 Businesses by Size 25 -26 Business Start Ups and Closures 26 -28 Business Start U ps 26 -27 Business Closures 27 -28 Business Survival Rates 28 -29 Business Location 29 -30 Employment Density 30 -31 Types of Employment 32 Business Sectors 32 -37 Gross Value Added 38 -40 GVA by Sector 39 -40 List of Figures Figure 1: Location of Shropshire 2 Figure 2: Levels of Deprivation in Shropshire, 2015 3 Figure 3: Main Means of Travelling to Work, 2011 4 Figure 4: Average Distances Travelled to Work, 2011 5 Figure 5: Commuter flows in Shropshire 5 Figu re 6: Commuting in and out of Shropshire, 1991 -2011 6 Figure 7: Cross -boundary commuting to and from Shropshire, 2011 6 Figure 8: Levels of Self -Containment across England and Wales 7 Figure 9: Population and Working Age Population Growth, 2001 -2015 8 Figure 10: Working Age Population as Percentage of Total Population, 2001 -2015 8 Figure 11: Population Pyramid for Shropshire: 2015 Mid -year 9 Figure 12: Development of the Shropshire Labour Force, 2005 -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for North

Shropshire Council Legal and Democratic Services Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Date: Monday, 25 March 2019 Committee: North Planning Committee Date: Tuesday, 2 April 2019 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Shrewsbury/Oswestry Room, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND You are requested to attend the above meeting. The Agenda is attached Claire Porter Head of Legal and Democratic Services (Monitoring Officer) Members of the Committee Substitute Members of the Committee Roy Aldcroft Nicholas Bardsley Gerald Dakin Joyce Barrow Pauline Dee Karen Calder Rob Gittins Steve Davenport Roger Hughes Ann Hartley Vince Hunt (Vice Chairman) Simon Jones Mark Jones Matt Lee Paul Milner David Minnery Peggy Mullock John Price Paul Wynn (Chairman) Brian Williams Your Committee Officer is: Emily Marshall Committee Officer Tel: 01743 257717 Email: [email protected] AGENDA 1 Apologies for Absence To receive apologies for absence. 2 Minutes (Pages 1 - 4) To confirm the Minutes of the meeting of the North Planning Committee held on 5th February 2019, attached, marked 2. Contact: Emily Marshall on 01743 257717 3 Public Question Time To receive any public questions or petitions from the public, notice of which has been given in accordance with Procedure Rule 14. The deadline for this meeting is 2.00 p.m. on Monday, 1st April 2019. 4 Disclosable Pecuniary Interests Members are reminded that they must not participate in the discussion or voting on any matter in which they have a Disclosable Pecuniary Interest and should leave -

Shropshire-Choices-Support-Finder-L

The Uplands KIND CARING Multi award-winning family owned Care Home FRIENDLY The Uplands is your very best choice for care with nursing in Shropshire. Set in glorious countryside on the EXPERIENCED outskirts of Shrewsbury, it provides spacious single en suite rooms with outstanding facilities, and offers the highest standards of dementia nursing and care for those PROFESSIONAL with long term conditions. • Specialists in end-of-life care, short term respite, rehabilitation and post-operative care • Experienced, professional and friendly staff • Full programme of activities in a true home- from-home • CQC rated Good in all standards • Two dedicated dementia units ‘Attentive caring attitude of nursing and care workers, compassion and patience demonstrated continually throughout Mum’s short stay.’ J T, Shropshire For more information call 01743 282040 or come and visit us at: arches The Uplands Clayton Way Care Bicton Heath Shrewsbury SY3 8GA See our consistently high customer reviews at: www.marchescare.co.uk The Uplands is owned and operated by Marches Care Ltd, part of the Marches Care Group. Welcome from Shropshire Council 4 I care for someone 46 Contents Areas covered by this Directory 5 Carers Support Service 46 Carers Emergency Response Service 46 Your health and wellbeing 6 Young Carers 47 Shropshire Choices 6 Local Support Swap 47 Healthy Shropshire 9 NHS Carers Direct 47 Let’s talk about the F-Word: preventing falls 10 Resource for those supporting disabled children 47 Shropshire Libraries: Books on Prescription 11 Money Matters 48 -

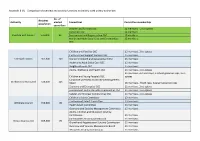

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

Cornwall Council) (Respondent) V Secretary of State for Health (Appellant)

Trinity Term [2015] UKSC 46 On appeal from: [2014] EWCA Civ 12 JUDGMENT R (on the application of Cornwall Council) (Respondent) v Secretary of State for Health (Appellant) R (on the application of Cornwall Council) (Respondent) v Somerset County Council (Appellant) before Lady Hale, Deputy President Lord Wilson Lord Carnwath Lord Hughes Lord Toulson JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 8 July 2015 Heard on 18 and 19 March 2015 Appellant (Secretary of Respondent (Cornwall State for Health) Council) Clive Sheldon QC David Lock QC Deok-Joo Rhee Charles Banner (Instructed by (Instructed by Cornwall Government Legal Council Legal Services) Department) Appellant /Intervener (Somerset County Council) David Fletcher (Instructed by Somerset County Council Legal Services Department) Intervener (South Gloucestershire Council) Helen Mountfield QC Sarah Hannett Tamara Jaber (Instructed by South Gloucestershire Council Legal Services) Intervener (Wiltshire Council) Hilton Harrop-Griffiths (Instructed by Wiltshire Council Legal Services) LORD CARNWATH: (with whom Lady Hale, Lord Hughes and Lord Toulson agree) Introduction 1. PH has severe physical and learning disabilities and is without speech. He lacks capacity to decide for himself where to live. Since the age of four he has received accommodation and support at public expense. Until his majority in December 2004, he was living with foster parents in South Gloucestershire. Since then he has lived in two care homes in the Somerset area. There is no dispute about his entitlement to that support, initially under the Children Act 1989, and since his majority under the National Assistance Act 1948. The issue is: which authority should be responsible? 2. This depends, under sections 24(1) and (5) of the 1948 Act, on, where immediately before his placement in Somerset, he was “ordinarily resident”. -

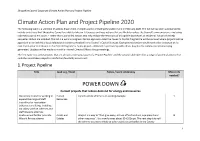

Climate Action Plan and Project Pipeline 2020 the Following Table Is a Selection of Actions Drawn from Multiple Sources Including the Public Event in February 2020

Shropshire Council Corporate Climate Action Plan and Project Pipeline Climate Action Plan and Project Pipeline 2020 The following table is a selection of actions drawn from multiple sources including the public event in February 2020. The full list has been summarised to include only those that Shropshire Council are able to take on. It focusses on those actions that are likely to reduce the Council’s own emissions – including indirect (Scope 3) emissions – rather than Council led actions that help reduce the emissions of Shropshire businesses or residents. Actions that help sequester carbon are included. This list is a work in progress. Formal approval under the Council’s Capital Programme will be pursued where projects will be appraised on an individual basis following the process detailed in the Council’s Capital Strategy. Each potential action would need to be evaluated on its own merits prior to inclusion in the Capital Programme. Some projects delivered in partnership with others may lead to commercial income being generated. Updates will be made at monthly internal Climate Officers Group meetings. The first table lists active projects that are already underway as part of a ‘Project Pipeline’ and the second table identifies a range of potential actions that could be undertaken subject to satisfactory feasibility assessment. 1. Project Pipeline Title Lead org / Dept Notes / work underway More info needed? POWER DOWN Current projects that reduce demand for energy and resources Shropshire Council is working to Human Cycle to Work scheme is an existing example Y expand the range of staff Resources incentives for low carbon behaviour and living, including via salary sacrifice schemes and staff rewards schemes. -

Shropshire Economic Development Needs Assessment Interim Report

Shropshire Economic Development Needs Assessment Interim Report Shropshire Council December 2020 © 2020 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd, trading as Lichfields. All Rights Reserved. Registered in England, no. 2778116. 14 Regent’s Wharf, All Saints Street, London N1 9RL Formatted for double sided printing. Plans based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright reserved. Licence number AL50684A 61535/01/SHo/CR 19104509v4 Shropshire Economic Development Needs Assessment : Interim Report Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 Introduction 1 Methodology 2 Report Structure 4 2.0 Economic Strategy and Policy Aspirations 5 Introduction 5 National 5 Regional 11 Local 13 3.0 Shropshire Socio-Economic Context 24 Introduction 24 Location 24 Population 25 Deprivation 29 Economic Resilience 30 Economic Conditions and Trends 33 Economic Competitiveness 43 4.0 Functional Economic Market Area 46 Introduction 46 Outline Description / Outline Methodology / Working Definition 46 Defining the Functional Economic Market Area 47 Conclusion: Shropshire’s Functional Economic Market Area 55 5.0 Overview of Employment Space 57 Introduction 57 Gross Completions 67 Losses 68 Development Pipeline 69 6.0 Stakeholder Consultation and Business Survey 73 Introduction 73 Key Stakeholders 73 Shropshire Economic Development Needs Assessment : Interim Report Shropshire Business Survey 74 7.0 Property Market Signals and Intelligence 79 Introduction 79 National and Regional Property Market Overview 79 Shropshire Property Market -

Telford & Wrekin Council/Shropshire County Council

SHROPSHIRE COUNCIL/TELFORD & WREKIN COUNCIL JOINT HEALTH OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE Minutes of a meeting of the Joint Health Overview and Scrutiny Committee held on 12 February 2015 in The Council Chamber, Shirehall, Shrewsbury from 2.10 pm – 4.20 pm PRESENT – Councillor D White (TWC Health Scrutiny Chair) (Chairman), Councillor G Dakin (SC Health Scrutiny Chair), Mr D Beechey (SC co-optee), Ms D Davis (TWC Health Co-optee), Mrs V Fletcher, Mr I Hulme (SC Co- optee), Cllr S Jones (SC), Mr J Minor (TW), Mr B Parnaby (TW Co-optee) Mrs M Thorn (SC Co-optee). Also Present – F Bottrill (Scrutiny Group Specialist, TWC) S Chandler (Director Adult Social Care, SC) L Chapman (Portfolio Holder, Adult Social Care, Shropshire Council) K Calder (Portfolio Holder Health, Shropshire Council) J Ditheridge (Chief Executive, Community Health Trust) A England (Cabinet Member for Adult Social Care, Telford & Wrekin Council) D Evans, (Accountable Officer, Telford & Wrekin CCG) A Holyoak (Committee Officer, Shropshire Council) M Innes (Chair, Telford & Wrekin CCG) C Morton (Accountable Officer, Shropshire CCG) A Osborne (Communications Director, SATH) M Sharon (Future Fit Programme Director) P Taylor (Director of Health, Wellbeing and Care, Telford & Wrekin Council) R Thomson, (Director of Public Health, Shropshire Council) I Winstanley (Chief Executive ShropDoc/GP Federation) The Chairman informed those present of the recent death of two co-opted Members of the Committee, Mr Richard Shaw, from the Senior Citizen’s Forum, Telford and Wrekin and Mr Martin Withnall, from Telford and Wrekin Healthwatch. It was agreed that a letter be sent from the Committee expressing condolences to their families and expressing gratitude for their valued contribution to its work. -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40.