Confronting the Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria: a New History of a Turbulent Century

More praise for Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century ‘This book is a major achievement and I defy anyone who reads it not to learn from it and gain greater understanding of the nature and development of a major African nation.’ Lalage Bown, professor emeritus, Glasgow University ‘Richard Bourne’s meticulously researched book is a major addition to Nigerian history.’ Guy Arnold, author of Africa: A Modern History ‘This is a charming read that will educate the general reader, while allowing specialists additional insights to build upon. It deserves an audience far beyond the confines of Nigerian studies.’ Toyin Falola, African Studies Association and the University of Texas at Austin About the author Richard Bourne is senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and a trustee of the Ramphal Institute, London. He is a former journalist, active in Common wealth affairs since 1982 when he became deputy director of the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington, and was the first director of the non-governmental Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. He has written and edited eleven books and numerous reports. As a journalist he was education correspondent of The Guardian, assistant editor of New Society, and deputy editor of the London Evening Standard. Also by Richard Bourne and available from Zed Books: Catastrophe: What Went Wrong in Zimbabwe? Lula of Brazil Nigeria A New History of a Turbulent Century Richard Bourne Zed Books LONDON Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century was first published in 2015 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK www.zedbooks.co.uk Copyright © Richard Bourne 2015 The right of Richard Bourne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Typeset by seagulls.net Index: Terry Barringer Cover design: www.burgessandbeech.co.uk All rights reserved. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Assessment of States' Response to the September

i ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSE TO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA FACULTY OF LAW DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE AUGUST, 2018 ii TITLE PAGE ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSETO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG. NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LAW IN THE DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE, FACULTY OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SUPERVISOR: PROF JOY NGOZI EZEILO (OON) AUGUST, 2018 iii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this research was carried out by Emeka C. Adibe, a post graduate student in Department of International law and Jurisprudence with registration number PG/Ph.D/13/66801. This work is original and has not been submitted in part or full for the award of any degree in this or any other institution. ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- ADIBE, Emeka C. Date (Student) --------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Supervisor) ------------------------------- ------------------------------- Dr. Emmanuel Onyeabor Date (Head of Department) ------------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Dean, Faculty of Law) iv DEDICATION To all Victims of Terrorism all over the World. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Gratitude is owned to God in and out of season and especially on the completion of such a project as this, bearing in mind that a Ph.D. research is a preserve of only those privileged by God who alone makes it possible by his gift of good health, perseverance and analytic skills. -

Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : the Role of Al-Azhar, Al-Medina and Al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Exploring Muslim Contexts ISMC Series 3-2015 Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor Keiko Sakurai Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc Recommended Citation Bano, M. , Sakurai, K. (Eds.). (2015). Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Vol. 7, p. 242. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc/9 Shaping Global Islamic Discourses Exploring Muslim Contexts Series Editor: Farouk Topan Books in the series include Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, “Islamic” and Neo-liberal Alternatives Edited by Robert Springborg The Challenge of Pluralism: Paradigms from Muslim Contexts Edited by Abdou Filali-Ansary and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Edited by Badouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots Cosmopolitanisms in Muslim Contexts: Perspectives from the Past Edited by Derryl MacLean and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena de Felipe Contemporary Islamic Law in Indonesia: Shariah and Legal Pluralism Arskal Salim Shaping Global Islamic Discourses: The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Edited by Masooda Bano and Keiko Sakurai www.euppublishing.com/series/ecmc -

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

Federal Republic Ofnigeria

wee . - “te. -“ fee= - . oa wes ™ LO we Same ¢, . rs 3* ae nN RB ArmA Baevaee fo iven COTE,avansreses Pre a Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette No.55 ° 7 oe Lagos- 21st September, 1989 Vol. 76 CONTENTS Page Movementsof Officers - - oe -« 878-903 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army—Dismissal, Voluntary Retirements, Discipline, Resignation, , Conversion, Award of Medals and Promotions . -- 90417 . ‘Trade Dispute Between the National Union of Road ‘TransportWorkers and Lagos State Transport Corporation 2 ee - “ -. 917 Trade Dispute Between the National Union of Hotels and Personal Services Workers and Unical Hotel, Calabar . -. .. as +. 917-18 Notice of Registration of Alteration of Trade Union Rules under Section 27 and 49 of the Trade ‘Union Act 1973 .. + 918 Loss of Custom Document . a - 919 AirTransport Licensing Regulations 1965 .s . os oe 919 Registration of Insurance Company o oe oe 919 Exemption and Extension of Exemption from the Provisions of Part "%?of the Companies Decree, 1968 underPowers Conferred bythe Companies (Special Provisions) Decree No. 19 of 1973 ++ 920-22 878 OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 55, Vol. 76 Government Notice No. 502 ; NEW ASTOINTMENTS AND: OTHER STAFF CHANGES ‘The following are notified for general information — NEW APPOINTMENTS . Department Name Appointment Date of Appointment Cabinet Office .. .. Idoghor, Miss M. ..| Clerical Officer 10-4-89 , Olajide, O «|: Motor Driver 6-6-78 © Popoola, F. Motor Driver _ 18-8-88 Civil ServiceCommission Adejumo,O, ..|, Assistant Craftsman we. 6-3-83 Ezeh, A. N. .4> Typist, Grade II .»: 21-12-79. Jjeh, F. -| Motor Driver - 17-3-80° John, O. -| Motor Driver =... 18-5-81 Oguno, Miss Cc, N. -

Boko Haram: an Assessment of Strengths, Vulnerabilities, and Policy Options

Boko Haram: An Assessment of Strengths, Vulnerabilities, and Policy Options Report to the Strategic Multilayer Assessment Office, Department of Defense, and the Office of University Programs, Department of Homeland Security January 2015 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Based at the University of Maryland 3300 Symons Hall • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 • www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The author of this report is Amy Pate, Research Director at START. Questions about this report should be directed to Amy Pate at [email protected]. The following Nigerian consultants assisted with field interviews: Bukola Ademola‐Adelehin (Abuja), Kop’ep Dabugat (Abuja and Kano), and Chris Kwaja (Jos). Sadiq Radda assisted in identifying informants and collecting additional published materials. The research could not have been completed without their participation. The following research assistants helped with the background research for the report: Zann Isaacson, Greg Shuck, Arielle Kushner, and Jacob Schwoerer. Michael Bouvet created the maps in the report. This research was supported by a Centers of Excellence Supplemental award from the Office of University Programs of the Department of Homeland Security with funding provided by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) office of the Department of Defense through grant award number 2012ST061CS0001‐ 03 made to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). The author’s travel to the field was supported by the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO) of the U.S. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

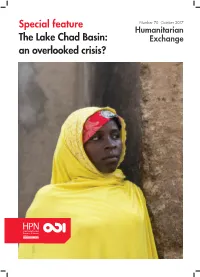

Special Feature the Lake Chad Basin

Special feature Number 70 October 2017 Humanitarian The Lake Chad Basin: Exchange an overlooked crisis? Humanitarian Exchange Number 70 October 2017 About HPN Contents 21. Integrating civilian protection into Nigerian military policy and practice The Humanitarian Practice Network 05. Chitra Nagarajan at the Overseas Development The Lake Chad crisis: drivers, responses Institute is an independent forum and ways forward 24. where field workers, managers and Toby Lanzer policymakers in the humanitarian Sexual violence and the Boko Haram sector share information, analysis and 07. crisis in north-east Nigeria experience. The views and opinions Joe Read expressed in HPN’s publications do The evolution and impact of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin not necessarily state or reflect those of 27. Virginia Comolli the Humanitarian Policy Group or the Mental health and psychosocial needs Overseas Development Institute. and response in conflict-affected areas 10. of north-east Nigeria A collective shame: the response to the Luana Giardinelli humanitarian crisis in north-eastern Nigeria 30. Patricia McIlreavy and Julien Schopp The challenges of emergency response in Cameroon’s Far North: humanitarian 13. response in a mixed IDP/refugee setting A square peg in a round hole: the politics Sara Karimbhoy of disaster management in north- eastern Nigeria 33. Virginie Roiron Adaptive humanitarian programming in Diffa, Niger Cover photo: Zainab Tijani, 20, a Nigerian refugee 16. Matias Meier recently returned from Cameroon in the home she shares with her family in the town of Banki, Nigeria, 2017 State governance and coordination of © UNHCR the humanitarian response in north-east Nigeria Zainab Murtala and Bashir Abubakar 17.