DOMESTIC WATER USE in the NEW 8UINEA HI6HLAN0S: the CASE of the RAIAPU ENGA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

Kosipe Revisited

Peat in the mountains of New Guinea G.S. Hope Department of Archaeology and Natural History, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Peatlands are common in montane areas above 1,000 m in New Guinea and become extensive above 3,000 m in the subalpine zone. In the montane mires, swamp forests and grass or sedge fens predominate on swampy valley bottoms. These mires may be 4–8 m in depth and up to 30,000 years in age. In Papua New Guinea (PNG) there is about 2,250 km2 of montane peatland, and Papua Province (the Indonesian western half of the island) probably contains much more. Above 3,000 m, peat soils form under blanket bog on slopes as well as on valley floors. Vegetation types include cushion bog, grass bog and sedge fen. Typical peat depths are 0.5‒1 m on slopes, but valley floors and hollows contain up to 10 m of peat. The estimated total extent of mountain peatland is 14,800 km2 with 5,965 km2 in PNG and about 8,800 km2 in Papua Province. The stratigraphy, age structure and vegetation histories of 45 peatland or organic limnic sites above 750 m have been investigated since 1965. These record major vegetation shifts at 28,000, 17,000‒14,000 and 9,000 years ago and a variable history of human disturbance from 14,000 years ago with extensive clearance by the mid- Holocene at some sites. While montane peatlands were important agricultural centres in the Holocene, the introduction of new dryland crops has resulted in the abandonment of some peatlands in the last few centuries. -

Indonesia (Republic Of)

Indonesia (Republic of) Last updated: 31-01-2004 Location and area Indonesia is an island republic and largest nation of South East Asia, stretching across some 5,000 km and with a north-south spread of about 2,000 km. The republic shares the island of Borneo with Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam; Indonesian Borneo, equivalent to about 75 per cent of the island, is called Kalimantan. The western half of New Guinea is the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya (formerly West Irian); the eastern half is part of Papua New Guinea. The marine frontiers of Indonesia include the South China Sea, the Celebes Sea, and the Pacific Ocean to the north, and the Indian Ocean to the south and west. Indonesia has a land area of 1,904,443 km2. (Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 2002). According to Geoanalytics (www.geoanalytics.com/bims/bims.htm) the land area of Indonesia comprises 1,919,663 km2. Topography Indonesia comprises 13,677 islands on both sides of the equator, 6,000 of which are inhabited. Kalimantan and Irian Jaya, together with Sumatra (also called Sumatera), Java (Jawa), and Celebes (Sulawesi) are the largest islands and, together with the insular provinces of Kalimantan and Irian Jaya, account for about 95 per cent of its land area. The smaller islands, including Madura, Timor, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, and Bali predominantly form part of island groups. The Moluccas (Maluku) and the Lesser Sunda Islands (Nusatenggara) are the largest island groups. The Java, Flores, and Banda seas divide the major islands of Indonesia into two unequal strings. The comparatively long, narrow islands of Sumatra, Java, Timor (in the Nusatenggara group), and others lie to the south; Borneo, Celebes, the Moluccas, and New Guinea lie to the north. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

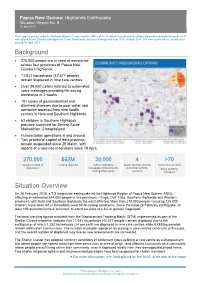

Background Situation Overview

Papua New Guinea: Highlands Earthquake Situation Report No. 8 20 April 2018 This report is produced by the National Disaster Centre and the Office of the Resident Coordinator in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by the Disaster Management Team Secretariat, and covers the period from 10 to 16 April 2018. The next report will be issued on or around 26 April 2018. Background • 270,000 people are in need of assistance across four provinces of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. • 11,041 households (42,577 people) remain displaced in nine care centres. • Over 38,000 callers listened to automated voice messages providing life-saving assistance in 2 weeks • 181 cases of gastrointestinal and diarrheal diseases due to poor water and sanitation reported from nine health centres in Hela and Southern Highlands. • 62 children in Southern Highlands province screened for Severe Acute Malnutrition; 2 hospitalized. • Humanitarian operations in and around Tari, provincial capital of Hela province, remain suspended since 28 March, with reports of a new rise in tensions since 19 April. 270,000 $62M 38,000 4 >70 people in need of funding required callers listened to health facilities started metric tons of relief assistance messages containing life- providing nutrition items awaiting saving information services transport Situation Overview On 26 February 2018, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake hit the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea (PNG), affecting an estimated 544,000 people in five provinces – Enga, Gulf, Hela, Southern Highlands and Western provinces, with Hela and Southern Highlands the most affected. More than 270,000 people, including 125,000 children, have been left in immediate need of life-saving assistance. -

Papua New Guinea Highlands and Mt Wilhelm 1978 Part 1

PAPUA NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS AND MT WILHELM 1978 PART 1 The predawn forest became alive with the melodic calls of unseen thrushes, and the piercing calls of distant parrots. The skies revealed the warmth of the morning dawn revealing thunderheads over the distant mountains that seemed to reach the melting stars as the night sky disappeared. I was 30 meters above the ground in a tree blind climbed before dawn. Swirling mists enshrouded the steep jungle canopy amidst a great diversity of forest trees. I was waiting for male lesser birds of paradise Paradisaea minor to come in to a tree lek next to the blind, where males compete for prominent perches and defend them from rivals. From these perch’s males display by clapping their wings and shaking their head. At sunrise, two male Lesser Birds-of-Paradise arrived, scuffled for the highest perch and called with a series of loud far-carrying cries that increase in intensity. They then displayed and bobbed their yellow-and-iridescent-green heads for attention, spreading their feathers wide and hopped about madly, singing a one-note tune. The birds then lowered their heads, continuing to display their billowing golden white plumage rising above their rust-red wings. A less dazzling female flew in and moved around between the males critically choosing one, mated, then flew off. I was privileged to have used a researcher study blind and see one of the most unique group of birds in the world endemic to Papua New Guinea and its nearby islands. Lesser bird of paradise lek near Mt Kaindi near Wau Ecology Institute Birds of paradise are in the crow family, with intelligent crow behavior, and with amazingly complex sexual mate behavior. -

Traditional Cartography in Papua New Guinea

12 · Traditional Cartography in Papua New Guinea ERIC KLINE SILVERMAN SOCIAL LIFE, COSMOLOGY, AND rather of social conventions such as gift exchanges that POLITICS IN MELANESIA enable people to continually forge and negotiate rela tionships and alliances. Gift exchange, first studied by The cultural diversity of Melanesia in the southwestern Marcel Mauss, is the basis for the constitution of tradi Pacific Ocean is astounding. Regional generalizations are tional or prestate societies in particular. 1 Guided by the bound to falter: some sociocultural exception to any principle of reciprocity, gift exchange refers to the moral posited rule will almost assuredly exist. Nevertheless, it is obligation to give, to receive, and to give back various ob possible at least to sketch some common, nearly pan jects such as food, tobacco, and valuables as well as labor Melanesian social and cultural parameters. Since all in and services. As a result, people are enmeshed in a web of digenous representations of space in Melanesia are the obligations whereby they are constantly giving and re product or the reflection of social life, this brief discus ceiving, thus holding the society together. All societies in sion will provide a necessary context for understanding Melanesia are at some level a group of people who speak the social generation of local modes of cartography. a common language, share the same culture, and form a The peoples of the first migration from Southeast Asia moral community united by gift exchange. spread into New Guinea, the larger islands off New However, there are other foundations of societies in Guinea, and Australia, which at that time were connected Melanesia, and although these vary greatly, they can be by a land bridge (fig. -

A Journey Through Austronesian and Papuan Linguistic and Cultural Space Papers in Honour of Andrew Pawley

A journey through Austronesian and Papuan linguistic and cultural space Papers in honour of Andrew Pawley edited by John Bowden, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann and Malcolm Ross with the editorial assistance of Edgar Suter Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Published by Pacific Linguistics School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Copyright in this edition is vested with Pacific Linguistics First published 2010 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: A journey through Austronesian and Papuan linguistic and cultural space : papers in honour of Andrew Pawley / edited by John Bowden, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann and Malcolm Ross. ISBN: 9780858836204 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Austronesian languages. Papuan languages. Historical linguistics. Other Authors/ Bowden, John. Contributors: Himmelmann, Nikolaus P., 1959- Ross, Malcolm, 1942- The Australian National University. School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Pacific Linguistics. Dewey Number: 499.2 Cover photo by Kevin Murray, Madang, Papua New Guinea, taken at Kalam Guest Hours, Simbai, 8th November, 2005. Fonj headdress from the Simbai area used for special ceremonial occasions, for example, initiation, pig killing and bride price payment ceremonies. Inside cover photos by Kevin Murray of Raphael from Kaiberim and Stanley from Suosu. Typeset by Jeanette Coombes Copyedited by Felicita Carr, Melissa Crowther and Lila San Roque Cover design by Julie Manley Printed and bound by Addcolour Digital Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, Canberra 13 The impact of a dynamic environmental past on trade routes and language distributions in the lower-middle Sepik PAMELA SWADLING Introduction1 Today small ships can travel up the Sepik River as far as Ambunti some 200 km as the crow flies from the sea (Figures 1–2). -

An Ethnobotanical Account of the Vegetation Communities of the Wola Region, Southern Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea

{oufllal of H/lIIobiolog.'l18(1 ):103-128 Summer 1998 AN ETHNOBOTANICAL ACCOUNT OF THE VEGETATION COMMUNITIES OF THE WOLA REGION, SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS PROVINCE, PAPUA NEW GUINEA PAULSLLLlTOE Durlmm Ulliversity 43 Old E/vet Durham, Eng/alld DHl 3HN ABSTRACT.-The vegetation communities distinguished by the Wola people of the Southern H..ighlands Province of Papua New Guinea are the subject of this paper, which complements a previous one on their botanical taxonomic scheme (jollfllal of Etllllobiology 15:201-235). The Wola identify nine vegetation types, with a further four sub-types, ranging from climax montane forest to seral communities of grassland. The composition of these communities is investigated, supported by data on plant species present. collected in a series of quadrat surveys (detailed. in Appendix). The number of species in each community is found to r.mge from 18 to 174. The Wola describe the vegetational communities 011 disturbed land as comprising an anthropogenic series of varying composition and species richness that is compared to the unaltered forest community. This paper is organized around this presumed ecological succession. While there is a broad correspondence between the local and scientific recognition of these ecological zones, which the quantitatiVE' data reinforce, the differences in these knowledge traditions should not be overlooked. Wola pt.'rceptionsareoutlinoo so far asapprehensible. Attitudes 10 human induced changes in vegetation cover arc also explored, and found to be equivocal. RESUMEN. - Las comunidades vegetacionales distinguidas par la gente wola de la Provincia de las TierrasAltas del Sur en Papua Nueva Guinea sonellema de este trabajo, quecomplementa Ull articulo previoacerca desu esquema laxon6mico botanicu (jol/fllal ofEthllobiology 15:201-235). -

Climate, Sea Level and Tectonic Controls on Sediment Discharge From

1 Climate, Sea Level and Tectonic Controls on Sediment Discharge from 2 the Sepik River, Papua New Guinea during the Mid- to Late Pleistocene 3 Aiello, I.W.1, Bova, S.C. 2, Holbourn, A.E. 3, Kulhanek, D.K.4, Ravelo, A.C.5 , and Rosenthal, Y.2 4 1 Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, 8272 Moss Landing Rd., Moss Landing, CA 95039 5 2Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences Rutgers, 71 Dudley Road, New Brunswick NJ 8521 6 3Institute of Geosciences, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Ludewig-Meyn-Strasse 14, Kiel 7 24118, Germany 8 4International Ocean Discovery Program, 1000 Discovery Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA 9 5Ocean Sciences Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz CA 10 95064 11 Abstract 12 Amongst the rivers draining the mountainous islands of the Indonesian Archipelago, the Sepik River 13 of Papua New Guinea is the largest contributor of solute and particulate material to the world ocean. Sites 14 U1484 and U1485, drilled during International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 363 provide 15 a continuous, ~555 kyr long, high-resolution record of mainly siliciclastic slope sedimentation on the 16 northern continental margin of PNG, just offshore the mouth of the Sepik River. Sedimentological 17 analysis, based on a combination of smear slide petrography, particle size analysis, high-resolution 18 physical properties track data and visual core description, offers an unprecedented opportunity to 19 investigate the evolution of this major tropical river throughout changing climate and sea-level conditions 20 during the mid- to late Pleistocene. The Sites U1484 and U1485 sediment records exhibit a dramatic 21 lithologic change at ~ 370 ka: the oldest deposits are dominated by pelagic mud, suggesting that the 22 coarser-grained terrigenous discharge from rivers draining the New Guinea Highlands (including a 23 “proto” Sepik River) was captured before reaching the ocean, when the Sepik River basin was an 1 24 epicontinental sea. -

Early Agriculture in the Highlands of New Guinea: an Assessment of Phase 1 at Kuk Swamp

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2004 Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 29 (2004): 47–57 ISBN 0-9750476-3-9 Early Agriculture in the Highlands of New Guinea: An Assessment of Phase 1 at Kuk Swamp TIM DENHAM Department of Archaeology, School of Humanities, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT. The wetland archaeological evidence for Phase 1 at Kuk Swamp, Wahgi Valley, Papua New Guinea, is evaluated in terms of previous interpretations of the artificiality and agricultural function of the palaeochannel and palaeosurface. The evaluation concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to warrant claims of artificiality for the palaeochannel and some palaeosurface elements. Drawing on previous multi-stranded arguments proposed by Jack Golson and Philip Hughes, new lines of multi- disciplinary evidence suggest a revised interpretation of the wetland archaeological evidence for Phase 1 at Kuk does not negate a long-term trajectory towards agriculture in the highlands of New Guinea from the Early Holocene. DENHAM, TIM, 2004. Early agriculture in the highlands of New Guinea: an assessment of Phase 1 at Kuk Swamp. In A Pacific Odyssey: Archaeology and Anthropology in the Western Pacific. Papers in Honour of Jim Specht, ed. Val Attenbrow and Richard Fullagar, pp. 47–57. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 29. Sydney: Australian Museum. Agriculture in the highlands: an old concern Phase 1 at Kuk Swamp, the only site for which agriculture at 9,000 B.P. has been claimed (Golson, 1977, 1989, 1991; The development and antiquity of agriculture in the Golson & Hughes, 1980; Hope & Golson, 1995: 824). -

Papua New Guinea Factsheet

FACT SHEETS PNG MAP AND OVERVIEW RUGBY LEAGUE IN PNG Rugby league was introduced to the country Made up of the Eastern half during the 1930s by Australian miners and played of New Guinea, and multiple by soldiers stationed there during and after World islands, located in the Pacific War II. Ocean. Papua New Guinea is the only country in the world Papua New Guinea is a to have rugby league as their national sport. mountainous country, and much PNG of it is covered with tropical The men’s national team are known as The Kumuls rainforest. (birds of paradise). The highest areas receive snow, The women’s national team are known as The which is rare in the tropics. Orchids. PNG is Famous for ... Having one of the highest diversities of languages in the world – there are 851 spoken languages amongst its population of 7.6 million! The New Guinea Highlands – a chain of mountain ranges and river valleys - run the length of the island of New Guinea. Researchers believe there are many undiscovered species of plants and animals in the interior. Edene Gebbie of PNG Highest Mountains LONGEST RIVERS MOUNT WILHELM 4,509M SEPIK RIVER 1,126KM MOUNT GILUWE 4,376M FLY RIVER 1,050KM MOUNT KUBOR 4,359M RAMU RIVER 640KM A brief history of PNG THE FLAG The first people in PNG crossed the Bering Straits from Asia. It was adopted in 1965, after much The first Europeans to explore the country were Vikings but they left debate. due to increasing conflicts with natives. In 1497, an Italian, John Cabot, Unofficially known as the Maple Leaf led an expedition to Newfoundland in PNG and made claim to the land after the leaf which adorns its middle for King Henry VII of England.