Creative Environments in Revitalizing Urban Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafikplan Indre Nørrebro.Pdf

23.9.2015 Trafikplan Indre Nørrebro Trafikplan Indre Nørrebro Udarbejdet af Grontmij + GHB landskabsarki- tekter for Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro, Teknik- og Miljøforvaltningen, Københavns Kommune. Version 1, September 2015 II Indhold Side Side Side A Resumé lll - lX 4 Forslag til Trafikstruktur 17 - 23 9 Bilag - Eksisterende Forhold 75 - 80 A.1 Ny trafikstruktur 4.1 Ny trafikstruktur (anbefalet løsning) 18 9.1 Kvarterets trafikstruktur 76 A.2 Ensretninger og spærringer 4.2 Nuværende trafikstruktur 18 9.2 Byliv 76 A.3 Lavere hastigheder 4.3 Hastighedsklassificering 19 9.3 Cyklisme 76 4.4 Vejlukninger og ensretninger 19 - 23 9.4 Sikre Skoleveje 77 9.5 Parkering 77 5 Sikre Skoleveje 25 - 27 9.6 Klimatilpasning 77 1 Forord 2 5.1 Hans Tavsens Gade 25 9.7 Ensretninger og Hastigheder 78 1.1 Mål og Visioner 3 5.2 Fodgængerfelt ved Skyttegade 25 9.8 Rantzausgade 78 1.2 Opgavens Indhold 3 og Blågårdsgade 9.9 Korsgade 78 1.3 Læsevejledning 3 4.3 Korsgade 25 9.10 Stengade 80 9.11 Griffenfeldsgade 80 2 Eksisterende Forhold 5 - 7 6 Parkering 29 - 31 9.12 Blågårds Plads 80 2.1 Kvarterets trafikstruktur 5 6.1 Nedlægelse af P-pladser 30 2.2 Byliv 5 6.2 Flexible P-pladser 30 2.3 Cyklisme 5 6.3 Nye parkeringsmuligheder 30 2.4 Sikre skoleveje 5 2.5 Parkering 5 7 Klimatilpasning 33 - 35 2.6 Klimatilpasning 5 7.1 Korsgade 34 2.7 Ensretninger og hastigheder 5 7.2 Rantzausgade 35 2.8 Rantzausgade 7 2.9 Korsgade 7 8 Forslag til Stedspecifikke 37 - 19 2.10 Stengade 7 Reguleringer og Ombygninger 2.11 Griffenfeldsgade 7 8.1 Rantzausgade 38 - 45 2.12 Blågårds Plads 7 8.2 Korsgade 46 - 49 8.3 Stengade 51 - 62 3 Byliv og Forbindelser 9 - 15 8.4 Griffenfeldsgade 63 - 65 3.1 Opholdsrum 10 - 12 8.5 Blågårds Plads 66 - 67 3.2 Forbindelser for Fodgængere 13 - 15 8.6 Baggesensgade 69 - 71 og Cyklister 8.7 Blågårds Skole 72 - 73 III Resumé A. -

I-Samtale-Med-København-2019.Pdf

I SAMTALE MED KØBENHAVN EN KVALITATIV ANALYSE AF BALANCEN MELLEM TURISME OG HVERDAGSLIV I KØBENHAVN I SAMTALE MED KØBENHAVN – En kvalitativ analyse af balancen mellem turisme og hverdagsliv i Kø- benhavn. Rapporten er udarbejdet for Wonderful Copenhagen. 2018. Analyse og tekst: Søren Møller Christensen, Christina Juhlin og Astrid Rifbjerg, carlberg | christensen. Opsætning og grafisk bearbejdning: Isabella Marchmann Hansen. Alle billeder og kortmateriale er udarbejdet af carlberg | christensen. INDHOLD INDLEDNING 1 KORTLÆGNING 2.2 - bevægelse og balance 15 FORMÅL 1 KORTLÆGNING 2.3 - overnatning og værtskab 17 METODE 1 KONKLUSIONER PÅ TVÆRS OG OPMÆRKSOMHEDSPUNKTER 19 EMPIRI 2 FORSLAG 20 OPBYGNING AF RAPPORT 2 DELANALYSE #1 DELANALYSE #3 Status: Hvad siger de lokale om turismen i København? 4 Københavns kvaliteter og kvarterer 23 DELKONKLUSIONER 4 DELKONKLUSIONER 23 PERSPEKTIV 4 PERSPEKTIV 23 KORTLÆGNING 1 5 KORTLÆGNING 3 24 KORTLÆGNING 1.1 - Turismens bidrag til byen 5 KORTLÆGNING 3.1 - kvalitetskortlægning 24 KONKLUSIONER PÅ TVÆRS OG OPMÆRKSOMHEDSPUNKTER 8 KORTLÆGNING 3.2 - kvartersportrætter 26 FORSLAG 8 Nørrebro 26 Vesterbro 28 DELANALYSE #2 Indre by 30 Synergier og konflikter mellem hverdagsliv og turisme 11 Byens nye områder 32 DELKONKLUSIONER 11 KONKLUSIONER PÅ TVÆRS OG OPMÆRKSOMHEDSPUNKTER 34 PERSPEKTIV 11 FORSLAG 35 KORTLÆGNING 2 12 KORTLÆGNING 2.1 - oplevelser og forskellige måder at opleve byen på 12 INDLEDNING FORMÅL METODE Formålet med denne analyse er at opbygge viden om og komme med forslag Analysen er udført af analyse- og rådgivningsvirksomheden carlberg/christen- til, hvordan turisme i København kan udvikle sig på en måde, der både er til sen i tæt samarbejde med Wonderful Copenhagens analyseteam. Analysen glæde for turisterne og københavnerne. -

Griffenfeldsgade - Gaden Der Aldrig Blir’ Mondæn Af Karsten Skytte Jensen

ÅRSSKRIFT 2017 1 Udgivet af: Foreningen og arkivet kan træffes efter NØRREBRO LOKALHISTORISKE aftale med formanden via e-mail: FORENING OG ARKIV [email protected] eller tlf. 22 92 14 05. Nr. 31, februar 2018 Undtagen i juli og august måned hvor vi ISSN: 1902-0422 holder sommerferie. Redaktion: E-mail: Foreningens bestyrelse. [email protected] Adresse: Karsten Skytte Jensen Hjemmeside: Balders Plads 4, 2. tv. www.noerrebrolokalhistorie.dk 2200 København N. Forsidebillede: Foreningens bestyrelse: Baggesensgade set fra Peblinge Formand: Dossering med hjørnet af Wesselsgade Karsten Skytte Jensen til venstre. Foto fra 1909 af Georg 22 92 14 05 Nikolaj Knub. Næstformand: Tryk: John Dickov Frydenberg A/S Kasserer: Ingrid Bøvith 20 70 52 08 Bestyrelsesmedlem: Anders Lillelund Suppleant: Josephine Grandlev Bonnevie 2 Årsberetning 2017 Foreningen og bestyrelsen guide fra Dansk Arkitektur Center viste Den 29. marts 2017 holdt Foreningen os rundt og fortalte om Superkilen og sin årlige generalforsamling. Tonny andre af de nye og spændende byrum, der Svanekiær var på valg, men ønskede ikke er kommet i bydelen de senere år. genvalg, samtidig udtrådte Vivi Chris- tensen af bestyrelsen. Ingrid Bøvith var Den 17. maj havde vi en rundvisning på på valg og blev genvalgt for en to-årig Blågårds Plads for Vanløse Lokalhis- periode. Anders Lillelund blev valgt til toriske Forening. Karsten Skytte Jensen bestyrelsen for en to-årig periode. Jose- var guide. phine Grandlev Bonnevie blev valgt til suppleant. Den 8. oktober holdt Uwe Brodersen et underholdende foredrag i Osramhuset Som revisor valgtes Anette Isted Lud- med titlen: De skæve eksistenser på vigsen og som suppleant Bodil Vendel. -

1125 Zzh50xbete.Pdf

Nørre Allé Nørre Blegdamsvej Meinungsgade Guldbergsgade Peter Fabers Gade Sankt Hans NY RENHOLDSORDNING HVAD GØR KOMMUNEN? Torv Møllegade Kan det blive nemmere og billigere at holde Københavns Kommune har ansvaret Ryesgade de offentlige fortove rene? Det har Teknik- for at holde fortovene rene i weekenden. og Miljøudvalget besluttet at undersøge. Og vi skal stadig tømme affalds kurve og Skt. Hans Gade holde veje, pladser samt cykelstier rene Kapelvej I dag betaler grundejerne kommunen for hele ugen. Solitudevej Elmegade at gøre rent på de offentlige fortove hele Fælledvej ugen. I den ny renholdsordning deler kom- SAMARBEJDE OG TILSYN Bangertsgade munen og grundejerne arbej det mellem I hele forsøgsperioden vil vi være meget sig, og grundejernes renholds udgift til opmærksomme på, hvordan det går med Nørrebrogade Ravnsborggade kommunen falder. at holde fortovene rene i jeres område. Tjørnegade Slotsgade Prins Baggesensgade Her GÆLDER DEN NYE ORDNING? Jørgens Sortedam Dossering Vi vil løbende føre tilsyn med jeres fortove Hans Tavsens Gade Vævergade Pilotforsøget med den nye renholds- og måle på, hvor rene de er. Vi vurderer Gade ordning starter den 1. januar 2014 og kvaliteten af renholds arbejdet på en skala Dronning Louises Bro løber til den 31. december 2015. fra 1 til 5, hvor 1 er dårligst og 5 er bedst. Det er vores målsætning, at gennemsnittet Todesade På kortet her til højre i folderen kan du se, skal ligge på 4,0. Stengade hvor på Indre Nørrebro ordningen gælder. Rantzausgade Blågårds Derudover er det vores mål at styrke sam- Plads Korsgade HVAD SKAL I GØRE? arbejdet med jer. Et godt samarbejde kan Blågårdsgade Som grundejer eller administrator skal sikre, at det bliver nemmere både for jer og Griffenfeldsgade du holde fortovene rene fra mandag til og os at holde fortovene rene, og at kvaliteten Gartnergade med fredag. -

Flood Prevention and Daylighting of Ladegårdsåen

Flood Prevention and Daylighting of Ladegårdsåen A Project to Create Green Space and to Provide Better Drainage of Rainwater SUBMITTED BY: Nésa-Maria Anglin Anthony Hassan Shane Ruddy SUBMITTED TO: Project Advisor: Prof. Lorraine Higgins Project Liaison: Anders Jensen May 4th, 2012 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science i Acknowledgements There are many people that we would like to thank for all of their support and input. Their help was invaluable and made our report much more complete and thorough. Many of our ideas and designs were adapted and developed from the guidance and suggestions we received. Anders Jensen: Miljøpunkt Nørrebro employee Ove Larsen: Miljøpunkt Nørrebro employee Lars Barfred: Miljøpunkt Nørrebro employee Søren Gabriel: Orbicon engineer Stefan Werner: Copenhagen Municipality employee, Water and Parks Division Aske Benjamin Akraluk Steffensen: Copenhagen Municipality intern, Water and Parks Division Thorkild Green: Municipality of Aarhus’ Department Architect Marina Jensen: Professor, Forest and Landscape at the University of Copenhagen Ole Helgreen: Aarhus Municipality Engineer, Water and Parks Division Oliver Bühler: Assistant Professor, Forest and Landscape at the University of Copenhagen Eigil Nybo: Architect Scott Jiusto: Professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute Lorraine Higgins: Professor, Director of Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) at Worcester Polytechnic Institute Suzanne LePage: Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute ii Authorship Page For our report, each team member worked on revising and editing all sections of this paper. Nésa-Maria Anglin Nésa-Maria transcribed and organized the previous proposal made by Orbicon which served as a basis for our design features and options for the canal. -

Nørrebro Tour a Livable & Sustainable Neighborhood?

Nørrebro Tour A livable & Sustainable Neighborhood?ROVSINGSGADE VERMUNDSGADE ALDERSROGADE g)Nørrebropark/ ROVSINGSGADE h)BanannaPark Superkilen HARALDSGADE This local neighborhood park has since its opening in 2009 found international NørrebroPark: Walk through this park. TAGENSVEJ interest. This park has become perticularly well recieved by local users. We nd a Notice the greenery, aesthetics and visual MJØLNERPARKEN very high amount of daily users. The three surrounding institutions (day-care, identity. Does this park correspond with grade school and after school activity center) use the park as their extended the demoraphics of the people using it? SKJOLDS schoolyard/gym/playground. Note the functions/programs of the park. Notice Which elements of the park stand out to PLADS the interaction/overlapping of the programs and thus also the user goups. Does you? Why? overlap of programs promote social interaction across user goups? Does diver- Superkilen: Continue across Hillerødgade sity of activity promote user goup diversity? Notice the visual identity of the and Nørrebrogade. You will get to a red HEIMDALSGADE park. Notice the surrounding windows, the park has 24-7 ’natural surveillance’ HERMODSGADE thermo-plast square; this is Red Square. JAGTVEJ (Jane RÅDMANDSGADEJacobs term). Note if the kids are accompanied by parents or on their Notice the urban furniture and the BORGMESTERVANGEN own? Does it feel safe? Does it feel livable? Can you tell this use to be a gang design of the square. Notice the peole and dealer hot spot? Would you consider this gentried or livable? HAMLETSGADE using it; is there social interaction bet- ween people? Continue further on to LYNGSIES Black Square. -

Ordinær Pulje 2014.Indd

BILAG 2 BBYGNINGSFORNYELSEYGNINGSFORNYELSE 22014014 BESKRIVELSE AF DE INDSTILLEDE PROJEKTER INSTALLATIONSMANGLER, UDSATTE BYOMRÅDER OG ENERGIOPTIMERING: 1. Kapelvej 51 / Rantzausgade 17 2. Baldersgade 67 3. Provstevej 10 4. Nørrebrogade 62 / Møllegade 1 5. Valdemarsgade 18-20 6. Hørsholmsgade 24-26 INSTALLATIONSMANGLER OG ENERGIOPTIMERING: 7. Gammeltoftsgade 22-24 8. Gothersgade 105 KLIMASKÆRM, UDSATTE BYOMRÅDER OG ENERGIOPTIMERING: 9. Ellebjergvej 2-36 / Haydensvej 1-7 / Sjælør Boulevard 47-57 10. Åboulevard 84-86 / Hans Egedes Gade 19-25 / Henrik Rungs Gade 14-18 / Jesper Broch- mands Gade 17 11. Henrik Rungs Gade 8-12 12. Enghavevej 31 / Matthæusgade 50-54 13. Bavnehøj Allé 15-17 / V. A. Borgens Vej 2-10 / Hans Olriks Vej 16-18 / Natalie Zahles Vej 1-7 14. Borgmestervangen 10-22 / Hothers Plads 1-35 / Midgårdsgade 5-15 15. Jagtvej 137 / Ydunsgade 1 16. Griff enfeldsgade 3 / Nørrebrogade 53A-B 17. Griff enfeldsgade 12-16 18. Slotsgade 7 19. Bulgariensgade 1 / Ungarnsgade 21-25 20. Mesterstien 1-20 / Rytterbakken 1-20 / Smedetoften 1-17 / Sokkelundsvej 32-46 / Svende- lodden 1-16 21. Kurlandsgade 31-33 22. Husumgade 15-17 23. Borups Allé 6-20 / Skotterupgade 1-11 / Humlebækgade 1-21 KLIMASKÆRM OG ENERGIOPTIMERING: 24. Brobergsgade 6-8 og 12-16 / Burmeistersgade 13 25. Gammel Kongevej 43 / Tullinsgade 2-4 26. Hauser Plads 16A-D 27. Engvej 172-178 / Hedegårdsvej 27-41 / Sumatravej 59-65 28. Livjægergade 33-35 29. Sølvgade 36 30. Borgergade 91 31. Jagtvej 157B-G / Lersø Parkallé 15-17 / Rådmandsgade 82-92 / Sifs Plads 5 og 11 / Skriver- gangen 2-8 32. Valkendorfsgade 36 33. Irlandsvej 64-70 / Hendonvej 4-10 / Sundbyvestervej 51-65 34. -

Nørrebrogade 5 Ahornsgade 22 Open Daily, 11:00-21:00

All Rights Reserved Rights All © 2019 City Hearts ApS Hearts City 2019 © we know a place a know we venues may occur without prior notice. prior without occur may venues MYPOKÉ PLANTEPØLSEN MOKKARIET ISTID VINBODEGAEN ARK BOOKS BE A WEAR SHOPPEN rect at time of printing. Changes regarding regarding Changes printing. of time at rect 1 6 11 15 19 24 29 34 - All information stated in this brochure is cor is brochure this in stated information All Birkegade 2 Jægersborggade 39 Jagtvej 72 Jægersborggade 13 Jægersborggade 56 Møllegade 10 Nørrebrogade 5 Ahornsgade 22 Open daily, 11:00-21:00. Tue-Sun, 12:00-17:00. Mon-Thu, 07:30-22:00. March-May: Tue-Wed, 17:00-23:00. Mon-Fri, 12:00-19:00. Mon-Fri, 10:00-18:00. Tue-Sat, 12:00-19:00. Fri, 07:30-21:00. Mon-Fri, 12:00-19:00. Thu, 17:00-24:00. Sat, 10:00-18:00. Sat, 10:00-17:00. www.cityhearts.dk SIDECAR / MAOBAO FALAFEL FACTORY HØKEREN 2 7 Sat-Sun, 08:30-21:00. Sat-Sun, 11:00-18:00. Fri-Sat, 16:00-24:00. Sun, 10:00-17:00. Sun, 12:00-17:00. 35 Skyttegade 5 Nørrebrogade 63 June-Aug: Ravnsborggade 13 RO CHOKOLADE THE BARKING DOG POLYMORPH FAIRYTAILOR Mon, 08:00-16:00*. Open daily, 11:00-21:00. 12 Mon-Fri, 12:00-21:00. 20 25 30 Tue-Thu, 12:00-18:00. or take the shortcut the take or - - Tue-Wed, 08:00-22:30*. Jægersborggade 16 Sat-Sun, 11:00-21:00. -

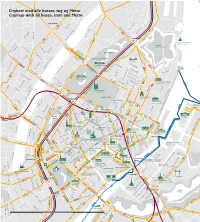

Byens Net Til

Citykort med alle busser, tog og Metro Citymap with all buses, train and Metro Rigshospitalet 3A Dag Hammerskjölds Allé Ryesgade Blegdamsvej Kristianiagade 26 1A 15 Østbanegade Øster Søgade Møllegade Nørre Allé Østerport st. 3A Folke Bernadottes Allé Sortedam Dossering 40 14 Den Lille Havfrue Blegdamsvej Øster Farimagsgade Little Mermaid Læssøesgade Fredensbro Kastellet Guldbergsgade Copenhagen Citadel 6A 42 43 Webersgade Møllegade Ryesgade Peter Fabers Gade Skt. Hans Gade 184 185 Østre Anlæg Stockholmsgade Sølvgade173E Nørrebrogade Store Kongensgade Elmegade 150S Hirschsprungs Samling Hirschsprung’s Collection 26 Nyboder Grønningen 3A 5A Stokhusgade Suensonsgade 6A Fælledvej 1A 184 185 Statens Museum 350S 15 Sølvgade for Kunst 1A Nordre Sortedam Dossering Danish National 173E 150S e Gernersgade 15 Toldbod NørrebrogadeRavnsborggade Gallery Griffenfeldsgade Øster Voldgade Øster Søgade Skt. Pauls Gade Esplanaden Baggesensgade Olfert Fischers Gade 3A Dr. Bartholinsgade Rigensgade Stengade Lo Botanisk Have onprinsessgad 14 40 42 43 5A uises Bro Botanic Garden Sølvgade Kr Fredericiagade 350S Klerkegade Øster Farimagsgade 26 15 Kunstindustrimuseet 901 Gothersgade 1A Frederiksborggade Museum of Art & Design 902 15 50S Adelgade 1A Korsgade Blågårdsgede 73E 1 1 42 43 Store Kongensgade Rosenborg Slot Borgergade Bredgade Gartnergade Wesselsgade Vendersgade 184 185 Rosenborg Casttle Amaliegade Arbejdermuseet 6A Øster Voldgade 26 5A Rømers- 14 gade Toldbodgade 350S Kongens Have Marmorkirken Smedegade Peblinge Dossering Dronningens TværgadeFrederik’s Church Nørreport st. Kronprinsessegade Davids Samling 350S 11 Gothersgade The David 26 Amalienborg Amalienborg Casttle Åboulevard Åbenrå Collection 11 11 Holmen 11 350S 26 12 66 69 Rosenborgg. Nørre Søgade Israels 66 Ahlefeldtsgade 11 Plads Filminstituttet Hausergade 11 Borgergade VognmagerDanish gade Film InstituteAdelgade Nansensgade Landemærket Linnésg. Kul- 11 350SGothersgade Amaliegade Fiolstræde 15Palægade 26 Skt. -

Trains & Stations Ørestad South Cruise Ships North Zealand

Svejager- Henningsens Bjergtoften NielsAndersens Vej Højgårds Allé Helsebakken Gersonsvej vej Allé På Højden Eggersvej Hellerupvej Jomsborgvej Fruevej Rødstensvej Stenagervej So Sønderengen fievej Grøns Mausoleum Ellemosevej j Svejgårdsvej Aftenbakken entorpsve årdsvej Vandtårnsvej Vilh. Niels FinsensAllé Dalstrøget Dalsv Kirkehøj Amm Onsg Forsvarsvej Batterivej Bergsøe Onsgårds Ø Tværvej stmarken Allé inget Byværnsvej j Aakjærs Allé é Hjemmevej Rygårds- Nordahl Griegs Vej Ravnekærsvej Thulevej C. V. E. Knuths Vej vænget Sydfrontve Erik Bøghs Allé Hellerup sens Vej Hellerupvej Søborg Park Allé Lykkesborg Allé ans Jen Lystbådehavn Ved Kagså H Strandparksvej Røntoftevej Stor j Frödings All Rake dyssen rove tsvej teb Munkegårdsvej Lyngbyvej Præs Hf. Mosehøj Stendyssevej Sydmarken Hyrdevej Hellerup Heller Dysse- en Hulkærsv Dagvej upgårdsv rd Marienborg Allé ej Dyssegårdsvej Lyngbyvej RygårdsAllé station ej Fr Gladsaxe Ringvej Sydmarken Knud RasmussensVej Dæmringsvej ederikkev stien dgå Wergelands Allé ej Langdyssen Søborg Ho Kodans- Mørkhøj Bygade Gladsaxe Møllevej Run ers Vej Vangedevej Skt. Ped Hillerødmotorvejen vej Kagsåvej Dyssebakken Dyssegårdsve Ruthsvej vedg j Marievej Hellekisten emosevej Almindingen Vand Gyng Gustav Runebergs Allé ade revej Esthersvej Knud Højgaards Vej Wieds Vej Callisensvej Dynamovej Transformervej Munkely Ewaldsbakken Bernstorffsvej Isbanevej vej Runddyssen Mindevej Helsingørmotorvejen Barkæret Carolinevej Tellers- Plantevej Nordkro Selma Lagerløfs Allé Grants Allé Morgenvej Hvilevej Rebekkavej g Vespervej Ardfuren -

Lokale Bydelskort Over København

Version. nov 2018 Version. we know a place lokale bydelskort over København Siden 2016 har vi udviklet vores lokale bydelskort, som nu dækker over Indre by, Nørrebro, Amagerbro og Vesterbro. Kortene fornyes én gang årligt, hvor de bliver trykt i 50.000 eksemplarer og jævnligt uddelt på alle Københavns hoteller. Det koster 3500,- ex. moms, for hele året. I denne flyer kan du blive lidt klogere på kortene og os. Læs mere om os på vores hjemmeside www.cityhearts.dk Drejervej FREDERIKSSUNDSVEJ The black HOTHERS PL. LYGTEN VIBEVEJ square HEJREVEJ HEIMDALSGADE nørrebro LUNDTOFTEGADEMIMERSGADE station ØRNEVEJ SVANEVEJ HAMLETSGADE MIDGÅRDSGADE NANNASGADE HEJREVEJ BALDERSGADE TAGENSVEJ BRAGESGADE NANNASGADE ÆGIRSGADE Titangade RÅDMANDSGADE NORDRE FASANVEJ Den røde plads SVANEVEJ VØLUNDSGADE Bus: 4A The red square FALKEVEJ FOGEDGÅRDEN JAGTVEJ UNIVERSITETS LUNDTOFTEGADE BRAGESGADE PARKEN BREGNERØDGADE ASMINDERØDGADE GLENTEVEJ BALDERSGADE ÆGIRSGADE ESROMGADE NØRREBROGADE JAGTVEJ NØRRE ALLÉ DAGMARSGADE THORSGADE Øster allé THYRASGADE HILLERØDGADE FARUMGADE FREJASGADE FÆLLEDPARKEN HILLERØDGADE MIMERSGADE RÅDMANDSGADE Østerbrogade P. D. LØVS ALLÈ Bus: 6A Olufsvej LUNDTOFTEGADE GORMSGADE ODINSGADE OLE MAALØES VEJ EDEL SAUNTES ALLÈ Krogerupgade SANDBJERGGADE GULDBERGS PL. GULDBERGS VEDBÆKGADE ALLERSGADE GULDBERGSGADE THORSGADE Bus: 5A ARRESØGADE JAGTVEJ JAGTVEJ REFSNÆSGADE Nørrebro vænge Nørrebro NØRREBROPRAKEN FREDERIK V’S VEJ NORDBANEGADE SØLLERØDGADE JAGTVEJ BISPEENGBUEN HENRIK HARPESTRENGS VEJ NORDRE FASANVEJ TIBIRKEGADE HOLTEGADE FENSMARKGADE JULIANE -

PROGRAMME NORDIC BUILT CITIES CHALLENGE Hans Tavsens Park, Blågård Skole & Korsgade

PROGRAMME NORDIC BUILT CITIES CHALLENGE Hans Tavsens Park, Blågård Skole & Korsgade February 2016 The programme is an appendix to the competition terms and conditions THE COMPETITION OVERVIEW HAS BEEN PRODUCED BY Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro CONTACT In cooperation with: Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro Construction Development Department Construction Management Department Julie Rosted [email protected] City Operations Eva Christensen [email protected] Nørrebro Park School, The Child and Youth Administration Local residents and actors through Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro The Technical and Environmental Administration, City of Copenhagen Nordic Built Cities under Nordic Innovation Steering committee and residents planning group under Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro: Sune Vinfeldt Svendsen Mette Bonde Mette Jokumsen Tommy Jensen Julie Trojaborg Bente Christiansen, Blågård School Katrine Marstrand Velco Jankovski Other actors that have contributed: PHOTOS Det Frie Gymnasium Christine Louw Miljøpunkt Nørrebro Jacob Toftager The staffed playgrounds Hans Tavsens West and Hans Tavsens East Julie Trojaborg Nørrebro Park School Mette Jokumsen Blagård School Katrine Marstrand Hellig Kors Church Sune Vinfeldt Svendsen Hellig Kors Kirke Københavns Kommune Layout: Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME TO PROJECT COMPETITION 4 READING GUIDE 6 1 THE PROJECT 9 SHARED VISION 10 THE PROJECT AREA 12 THE THREE PART-ASSIGNMENTS 16 2 THE THREE SUBAREAS 21 HANS TAVSENS PARK 22 BLÅGÅRD SCHOOL 36 KORSGADE 48 3 TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS 63 CLIMATE ADAPTATION 64 TRAFFIC PLAN FOR INNER NØRREBRO 68 ZONING REGULATIONS 70 ECONOMY / CONTRACTER BUDGET 70 RELEVANT POLICIES AND REQUIREMENTS 71 APPENDICES 71 3 WELCOME TO PROJECT COMPETITION WELCOME to the project competition for Nor- dic Built Cities - Hans Tavsens Park, Blågård School and Korsgade. Residents of Nørrebro, Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro1, public officials and politicians from the City of Copenhagen and partners from Nordic Built Cities Challen- ge have cooperated in producing this competi- tion overview.