Season Extension Introduction and Basic Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Concepts of Season Extension and Use

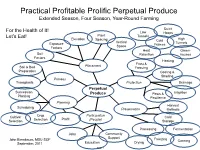

Practical Profitable Prolific Perpetual Produce Extended Season, Four Season, Year-Round Farming Quick For the Health of It! Low Hoops Let’s Eat! Plant Tunnels Elevation Spacing High Vertical Cold Exposure Frames Tunnels Factors Space Heat Green- Soil Retention houses Factors Heating Frost & Placement Soil & Bed Freezing Preparation Cooling & Shading Process Transplants Protection Drainage Perpetual Succession Produce Pests & Irrigation Planting Pestilence Planning Harvest Scheduling Preservation Methods Cultivar Crop Participation Cold Profit Selection Selection (People) Storage Processing Fermentation Jobs Community Support Freezing John Biernbaum, MSU-SOF Canning September, 2011 Education Drying Page 2 Warm soybean Cool snap bean lettuce Season peas Season lima bean baby leaf salad mix popcorn spinach 12. Beans chard beet sweet corn And Peas 1. Salad mustard Greens 11. Corn tatsoi winter pac choi 2. Cooking pumpkin Vegetable Planning kale Greens collard summer 10. Squash What to grow? How much to grow? cabbage cucumber When to grow it? broccoli 3. Cole 9. Cucumbers Where to grow it? cauliflower melon Crops and Melons How to grow it? kohlrabi watermelon How to harvest it? Brussels sprouts How to store it? scallions tomato 8. Summer How to market it? 4. Onions onions Fruits and Flavor pepper garlic leek eggplant 5. Root okra 7. Perennials carrot celery Crops celeriac tomatillo 6. Potatoes beet bulb fennel asparagus turnip rhubarb sunchoke parsnip radish Leaves, Seeds and horseradish sweet potato potato rutabaga and Roots Fruits John Biernbaum, MSU, 2009 Perpetual Produce Simple season extension for year-round farming. Prepared by John Biernbaum MSU Horticulture and Student Organic Farm Whether we call it “fair food”, “good food” or “local food”, the message is the same. -

High Tunnels

High Tunnels Using Low-Cost Technology to Increase Yields, Improve Quality and Extend the Season By Ted Blomgren and Tracy Frisch Produced by Regional Farm and Food Project and Cornell University with funding from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program Distributed by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture High Tunnels Authors Ted Blomgren Extension Associate, Cornell University Tracy Frisch Founder, Regional Farm and Food Project Contributing Author Steve Moore Farmer, Spring Grove, Pennsylvania Illustrations Naomi Litwin Published by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture May 2007 This publication is available on-line at www.uvm.edu/sustainableagriculture. Farmers highlighted in this publication can be viewed on the accompanying DVD. It is available from the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405. The cost per DVD (which includes shipping and handling) is $15 if mailed within the continental U.S. For other areas, please contact the Center at (802) 656-5459 or [email protected] with ordering questions. The High Tunnels project was made possible by a grant from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program (NE-SARE). Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, Vermont. University of Vermont Extension, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, cooperating, offer education and employment to everyone without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status. -

Indiana High Tunnel Handbook

Horticulture & Landscape Architecture ag.purdue.edu/hla HO-296 Indiana High Tunnel Handbook Analena Bruce, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Indiana University Elizabeth Maynard, Clinical Engagement Assistant Professor of Horticulture, Purdue University James Farmer, Associate Professor and Co-Director of IU Campus Farm, Indiana University Jonas Carpenter, Bread and Roses Nursery, LLC HO-296-W Photo Credits Photos provided by Erin Bluhm, Analena Bruce, William Horan, Richard Kremer, Jon Leuck, Jonas Carpenter, and Elizabeth Maynard Acknowledgements This publication was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service Specialty Crop Block Grant #15-002. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USDA. The patience and expertise of the farmers who participated in the high tunnel study was essential to the production of this book. We’d like to thank all participating farmers for their generosity and willingness to share their experiences and advice with others. We also thank the reviewers: Wenjing Guan and Petrus Langenhoven from the Purdue Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture; Adam Heichelbech from the Indiana Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS); and farmers Linda Chapman, Genesis McKiernan-Allen, and Richard Ritter, who contributed to and strengthened this book. The authors assume responsibility for any errors or flaws. 2 HO-296-W Why High Tunnels? the cooler months and planting earlier in the spring High tunnel crop production has grown immensely (crops such as lettuce, spinach, and kale). Another half in the past decade, particularly among specialty crop only use the structures in summer to improve the growth growers who sell directly to consumers. -

The Tennessee Vegetable Garden: Season Extension Methods

THE BACKYARD SERIES W 346-F BACKYARD VEGETABLES THE TENNESSEE VEGETABLE GARDEN SEASON EXTENSION METHODS Natalie Bumgarner, Assistant Professor and UT Extension Residential and Consumer Horticulture Specialist Department of Plant Sciences Vegetable production is increasingly of conditions — thus extending the popular for Tennessee residents. THE WHY AND growing season. Growing vegetables at home WHAT OF SEASON This practice of season extension allows provides financial and nutritional EXTENSION gardeners to have some control over benefits through the bounty of the environment around their crops a fresh harvest, and the activity (roots and/or shoots) to enhance One of the basic facts of gardening enhances personal health and productivity or maintain survival until is that crops will grow, develop and well-being. However, a basic conditions are more appropriate for produce when temperatures are growth. Certainly there are limits, but understanding of soils, site selection appropriate. Gardeners carefully plant adding an extra few days to weeks and crop maintenance is required cool- and warm-season crops to grow to the growing season can be quite before backyard growers can take during the time of year that targets useful in vegetable gardens. Methods full advantage of the benefits of their ideal temperature range. Managing are divided into two main groups: home food production. To meet crops according to surrounding management practices that can extend conditions can work very well and fit these needs, this series of fact growing periods and structures or the needs of many gardeners. However, sheets has been prepared by UT materials that can be used to alter gardeners have the option of altering Extension to inform home gardeners temperatures and extend seasons. -

A GUIDE to SEASON EXTENSION for Illinois Specialty Crop Growers

A GUIDE to SEASON EXTENSION for Illinois Specialty Crop Growers Terra Brockman, Cara Cummings, Jeff Hake Cover photo of Henry’s Farm, Congerville, IL by Terra Brockman Henry Brockman of Henry’s Farm got creative with season extension, using every bucket and basket he could find to create warmer microclimates around each tender transplant. Because if you’ve invested in great cultivars, and a hoophouse to start them in, and then transplanted them all to the fields in mid-May, you need to make sure they won’t all die when a late frost is predicted. And yes, they survived! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Land Connection thanks the following people for their valuable contributions of time and expertise as we developed this guide: Lorien Carsey of Blue Moon Farm, Urbana, Illinois Alisa DeMarco of Prairie Fruits Farm & Creamery, Champaign, Illinois Marty Gray of Gray Farms, Watseka, Illinois Marnie Record of the Illinois Organic Growers Association Clay Yapp of Sola Gratia Farm, Champaign, Illinois We also thank Kira Santiago for her designing of this guide, and Tim Meyers for his excellent recording and editing of our three case-study videos. Federal funds for this project were provided by the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program of the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, through the Illinois Department of Agriculture. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .......................................................2 Introduction .............................................................4 What is Season Extension? .................................................5 -

Sequential Planting of Cool Season Crops in a High Tunnel

Many Crops, Many Plantings to Maximize High Tunnel Production Efficiency ©Pam Dawling 2018 Twin Oaks Community, Central Virginia Author of Sustainable Market Farming and The Year-Round Hoophouse SustainableMarketFarming.com facebook.com/SustainableMarketFarming What’s in this Presentation 1. Multi-crop Hoophouses 2. Suitable Crops for Cold Weather 3. Suitable Crops for Warm Weather 4. Suitable Crops for Hot Weather 5. Packing More Crops in: Follow-on Crops, Filler Crops, Interplanting, Bare-root Transplanting 6. Succession Planting 7. Crop Rotations 8. Planning and Scheduling 9. Record-keeping 10. Resources I live and farm at Twin Oaks Community, in central Virginia. We’re in zone 7, with an average last frost April 30 and average first frost October 14. Our goal is to feed our intentional community of 100 people with a wide variety of organic produce year round. Our Hoophouse at Twin Oaks • We have one 30’ x 96’ FarmTek ClearSpan gothic arch hoophouse. • We put it up in 2003, and like many growers we had the primary goal of growing more winter greens, early tomatoes and peppers. • We grow many different crops, rotating them as best we can. • Our hoophouse is divided lengthwise into five 4’ beds and a 2’ bed along each edge. • Our paths are a skinny 12” wide - maximum growing space. Winter Hoophouses Protection of 2 layers of plastic and an air gap: 8F (5C) warmer than outside on cold nights . Single layer hoophouses are not much warmer at night than outdoors. Plants tolerate colder temps than they do outside, even without adding any inner rowcover In our double layer hoophouse in zone 7, without inner rowcover, salad greens survive when it’s 14F (-10C) outside. -

A Thriving Student Organic Farm at a Land Grant University

Four-Season Student Farming John Biernbaum, Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University How do you tell the story? How much from the head and how much from the heart? Is it a narrative grounded in the academic literature, or is it rather a story about place, people, process and transformational change? The history of the Michigan State University Student Organic Farm (MSU- SOF) can be told in many ways. The account offered here is from the perspective of a tenured faculty member and professor who partnered with students, staff and other colleagues to cultivate what has developed into a thriving student organic farm at a land grant university. The intent is to paint an instructive picture for those seeking to start similar farms at other schools, as well as for those walking the path of personal growth in a "learning-farm" culture. The MSU-Student Organic Farm started as a location for organic high tunnel research and quickly expanded to a 48-week community supported agriculture (CSA) program to research and demonstrate year-round vegetable production and to provide students with organic farming experience. From the beginning, the goal of the MSU Student Organic Farm has been to incorporate student requests for practical organic farming opportunities with the additional need for research, outreach and service to the campus and local communities. Creating an integrated program has been a key objective, as well as a budgetary reality, for the SOF from the start. A research project established the site and funded the first two high tunnels, providing a foundation for later expansion. -

Program Schedule

Program Schedule SUNDAY/MONDAY 104th Annual International Conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science Westin Kierland Resort and Spa, Scottsdale, Arizona of Horticulture Departments into general Plant Science programs, Sunday, July 15 and the decreasing population of graduate students and faculty who identify as being Horticulturists are having immediate and long term affects on the Profession of Horticulture, and on ASHS. 7:00–6:00 pm Concurrently, the margins of the Horticulture industry have been Sedona & Montezuma Castle National Monument Tour reduced with increased competition, consolidation and globaliza- Travel back in time to Montezuma Castle National Monument. The tion. ASHS must reposition and readapt itself to this changing short path to this prehistoric Sinagua Indian cliff dwelling along environment. The ASHS Certified Horticultural Advisor Program the banks of beautiful Beaver Creek. The next stop on the tour (ASHS-CHA) is an opportunity to professionalize and enhance the takes you to the amazing red rocks of Sedona, where you can find relevancy of both traditional and emerging areas of Horticulture, yourself surrounded by such famous rock formations as Bell Rock encourage and attract young people seeking careers in the field, and and Cathedral Rock, and you will experience the serene beauty of to better serve the industry. Oak Creek Canyon. Bring your camera! The ASHS-CHA is a national program to define and validate the horticultural competency of working horticultural practitioners in 8:00–3:00 pm the horticulture industry and/or profession who may or may not have Boyce Thompson Arboretum Tour a 4-year college degree (in Horticulture or a closely related field). -

Season Extension

SEASON EXTENSION A Plain Language Guide from the New Entry Sustainable Farming Project IN THIS GUIDE, YOU WILL LEARN ABOUT: The benefits and costs of extending the growing season Simple methods of season extension Materials and costs for season extension New Entry Sustainable Farming Project World PEAS Cooperative Authored by Jeff Hake Reviewed by Jennifer Hashley, New Entry Director Graphic Design by Zoe Harris www.nesfp.org November 2010 Boston Office: New Entry Sustainable Farming Project Agriculture, Food and Environment Program Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition and Science Policy Tufts University 75 Kneeland Street Boston, MA 02111 (617) 636-3793 Lowell Office: New Entry Sustainable Farming Project 155 Merrimack Street, 3rd Floor Lowell, MA 01852 (978) 654-6745 For additional information regarding this document, please email: [email protected], or call (978) 654-6745. This document is available in electronic format or as a printed copy. The latter may be obtained by contacting NESFP at the above locations. Please contact New Entry for permission to use any part of this document for educational purposes. Production of this document was supported by USDA Risk Management Agency (RMA Partnership Agreement No. 06IE08310159). “In accordance with Federal law and US Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Ave SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410. Or call (202) 720-5964. USDA is an equal opportunity employer.” Season Extension Purpose of this Guide Who should read this guide? This guide is written for people who want to know how to extend their growing season into the winter. -

The Promise of Urban Agriculture, National Study of Commercial

The Promise of Urban Agriculture National Study of Commercial Farming in Urban Areas Report Authors Dr. Anu Rangarajan and Molly Riordan Federal Project Lead Samantha Schaffstall August 2019 A Preferred Citation Rangarajan, A., & Riordan, M. (2019). The Promise of Urban Agriculture: National Study of Commercial Farming in Urban Areas. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Marketing Service and Cornell University Small Farms Program. USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender. B Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: The Promise of Urban Agriculture ................................................................................. 5 Types of Urban Farms ................................................................................................................................6 Exploring Commercial Urban Agriculture ..................................................................................................7 Structure of the Report ..............................................................................................................................8 Chapter 2: Study Methods .............................................................................................................. 9 Understanding Perspectives on Commercial -

Resource Guide to Organic and Sustainable Vegetable Production

A project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology 1-800-346-9140 • www.attra.ncat.org Resource Guide to Organic and Sustainable Vegetable Production By Steve Diver Introduction with a few mouse clicks many of these items now NCAT Agriculture instantly appear on your computer screen. Bet- Specialist armers making a transition to sustainable ter yet, most of these articles and bulletins are Published 2001 or organic farming need information on a free. In addition, some items—including many Updated May 2012 wide variety of topics such as soil manage- Extension Service fact sheets—are available only By Tammy Hinman, Fment and non-chemical weed and pest manage- in electronic form. Thus, some portions of this Andy Pressman, and ment. This guide provides a summary of some Hannah Sharp, NCAT resource list are more heavily oriented to Web of the best in-print and online sources around. Agriculture Specialists resources than others. ©NCAT Here it should be noted that farmers raising herbs If you have received this resource list but you IP188 or field-grown cut flowers face nearly identical don’t have a computer at home, please see your production requirements. Thus, when we talk Contents about cover crops or weed control or soil man- local public library for assistance. Introduction ......................1 agement for vegetables, the same approach will The Farmer’s work for field-grown cut flowers and herbs. How to Read Web Documents Bookshelf ...........................2 .HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language) means Organic Farming Primer ..................................5 Who Should Use This Guide that you can click and read online. -

Season Extension Off-Grid Greenhouse AAIG Grant Recipient Project Report 2012 Allie Barker

Season Extension Off-Grid Greenhouse AAIG Grant Recipient Project Report 2012 Allie Barker I am delighted to say that this project has been innovative in more ways than one. Simply searching the world of Google, local libraries, and sharing stories with experienced growers in AK was not enough to paint the picture of how to successfully build this greenhouse. Originally inspired by the effort and diligent experimentation of season extension entrepreneurs, Anna Eddy of Solviva, and Eliot Coleman of Four Season Farm, I was encouraged to utilize their lessons learned while drawing upon my own experience to create a unique greenhouse. The lack of quality, year round, local food in Alaska fed my desire to grow food earlier and later in the season without electricity and lights. However, challenged by sun angles ranging from low to none, with extreme cold temperatures, presented a feat I knew would require some gambling and combining of ideas. I have dreamt of undertaking a project such as this for the past 10 years. When I received this grant, I knew it was time to make the dream a reality. Building this greenhouse has been an unbelievable experience in learning, problem solving, persistence, and rewards. When I initially wrote the grant proposal I intended to design and build an off-grid permanent greenhouse out of recycled milk carton bales, locally milled spruce, wood heat, radiant floor heat under the beds, and passive solar techniques to maximize and utilize the heat and energy from the sun to grow plants earlier and later in the season. Although I adhered to most of my initial intentions, others changed due to external factors.