A New Production Culture and Non-Commodities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Tools for Artistic Consciousness of the People

34 commentary peer-reviewed article 35 that existed in the time of the Russian of the transformations in the urban space contents Revolution and those political events that of an early Soviet city. By using the dys- 33 Introduction, Irina Seits & Ekaterina influenced its destiny and to reflect on topian image of Mickey Mouse as the de- Kalinina the reforms in media, literature, urban sired inhabitant of modernity introduced peer-reviewed articles space and aesthetics that Russia was go- by Benjamin in “Experience and Poverty” 35 Becoming tools for artistic ing through in the post-revolutionary Seits provides an allegorical and com- consciousness of the people. decades. parative interpretation of the substantial The higher art school and changes in the living space of Moscow independent arts studios Overview of that were witnessed by Benjamin. in Petrograd (1918–1921), the contributions Mikhail Evsevyev Mikhail Evsevyev opens this issue with TORA LANE CONTRIBUTES in this issue with 45 Revolutionary synchrony: an analysis of the reorganization of the her reading of Viktor Pelevin’s Chapaev i A Day of the World, Robert Bird Higher Artistic School that was initiated Pustota (transl. as Buddha’s Little Finger or 53 Mickey Mouse – the perfect immediately after the Bolshevik Revolu- Clay Machine Gun), by situating her analy- tenant of an early Soviet city, tion in order to make art education ac- ses within the contemporary debates on Irina Seits cessible to the masses and to promote art realism and simulacra. She claims that Becoming 63 The inverted myth. Viktor as an important tool for the social trans- Pelevin, in his story about the period of Pelevin’s Buddhas little finger, formations in the Soviet state. -

Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 39 (# 21) Year 2018. Page 18 Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia Problemas para mejorar la calidad de la enseñanza de las Bellas Artes en la Escuela de Educación General en la Rusia moderna Elena S. MEDKOVA 1 Received: 12/01/2018 • Approved: 06/02/2018 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods 3. Results 4. Discussion 5. Conclusion Acknowledgements References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article considers topical problems of teaching fine El artículo considera los problemas actuales de la arts in general education school of modern Russia on enseñanza de las bellas artes en la escuela de the basis of mastering models of artistic thinking educación general de la Rusia moderna sobre la base based on the achievements of modern and de dominar los modelos de pensamiento artístico contemporary art. The author gives a detailed basados en los logros del arte moderno y historical digression of the contradictory history of the contemporáneo. El autor ofrece una digresión introduction of avant-garde ideas into the educational histórica detallada de la historia contradictoria de la process of higher school and general education introducción de ideas vanguardistas en el proceso schools throughout the 20th century in Russia. The educativo de las escuelas de educación superior y article presents the materials of the research of the educación general a lo largo del siglo XX en Rusia. El modern state of teaching fine arts in school. It artículo presenta los materiales de la investigación del analyzes the content of the most popular textbooks estado moderno de la enseñanza de las bellas artes on fine arts from the positions of balance in their en la escuela. -

Serge Diaghilev's Art Journal

Mir iskus8tva, SERGE DIAGHILEV'S ART JOURNAL As part of a project to celebrate Seriozha, and sometimes, in later years, to the three tours to Australia by the dancers who worked for him, as Big Serge. Reputedly he was of only medium height Ballets Russes companies between but he had wide shoulders and a large head 1936 and 1940, Michelle Potter (many of his contemporaries made this looks at a seminal fin de siecle art observation). But more than anything, he journal conceived by Serge Diaghilev had big ideas and grand attitudes. When he wrote to his artist friend, Alexander Benois, that he saw the future through a magnifying 'In a word I see the future through a glass, he could have been referring to any magnifying glass'. of his endeavours in the arts. Or even to - Serge Diaghilev, 1897 his extreme obsessions, such as his fear of dying on water and his consequent erge Diaghilev, Russian impresario deep reluctance to travel anywhere by extraordinaire, was an imposing person. boat. But in fact, in this instance, he was SPerhaps best remembered as the man referring specifically to his vision for the behind the Ballets Russes,the legendary establishment of an art journal. dance company that took Paris by storm in This remarkable journal, Mir iskusstva 1909, he was known to his inner circle as (World of Art). which went into production dance had generated a catalogue search on Diaghilev, which uncovered the record. With some degree of excitement, staff called in the journals from offsite storage. Research revealed that the collection was indeed a full run. -

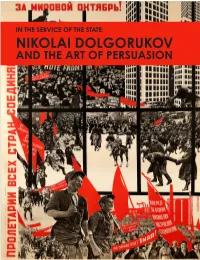

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century Elena S. Stetskevich The early days of the Academy The Russian Academy of Sciences was founded in 1724.1 During the first half of the eighteenth century, it was the unique scientific, educational, artistic and publishing center in Russia. The Academy consisted of different parts, including the first Russian university, a secondary school (“gymnasium”), library, public museum (Кунсткамера/ “Kunstkamera”), astronomical observatory and anatomical theater. The wide range of tasks of the Academy included the development of natural sciences and humanities, teaching of youth in science and dissemination of knowledge in the country. Along with the cultivation of sciences, the Academy was also planned to organize the training of artistic disciplines.2 The draft regulation from 1725, which was not approved, witnesses the fixed intention to open an Academy of Arts within the Academy of Sciences. It was assumed that the Academy of Arts could be used to teach those students who express the desire to learn artistic practices, as well as those who were unable to study at a gymna- sium.3 However, this intention was not implemented, as the founder of the Academy of Sciences – Tsar Peter the Great (1682–1725) – died before he could approve the regulation. However, drawing education was included in the program of the academic gym- nasium as a mandatory subject. It was taught one hour a day, four times a week, in the afternoon.4 Originally, these lessons were conducted by artists who were members of 1 The ‘Russian Academy of Sciences’ had different names in the first half of the eighteenth century, including ‘The Academy of Arts and Sciences’ and the ‘Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts in St. -

Cultural Syllabus : Russian Avant-Garde and Radical Modernism : an Introductory Reader

———————————————————— Introduction ———————————————————— THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE AND RADICAL MODERNISM An Introductory Reader Edited by Dennis G. IOFFE and Frederick H. WHITE Boston 2012 — 3 — ——————————— RUSSIAN SUPREMATISM AND CONSTRUCTIVISM ——————————— 1. Kazimir Malevich: His Creative Path1 Evgenii Kovtun (1928-1996) Translated from the Russian by John E. Bowlt Te renewal of art in France dating from the rise of Impressionism extended over several decades, while in Russia this process was consoli- dated within a span of just ten to ffteen years. Malevich’s artistic devel- opment displays the same concentrated process. From the very begin- ning, his art showed distinctive, personal traits: a striking transmission of primal energy, a striving towards a preordained goal, and a veritable obsession with the art of painting. Remembering his youth, Malevich wrote to one of his students: “I worked as a draftsman... as soon as I got of work, I would run to my paints and start on a study straightaway. You grab your stuf and rush of to sketch. Tis feeling for art can attain huge, unbelievable proportions. It can make a man explode.”2 Transrational Realism From the early 1910s onwards, Malevich’s work served as an “experimen- tal polygon” in which he tested and sharpened his new found mastery of the art of painting. His quest involved various trends in art, but although Malevich firted with Cubism and Futurism, his greatest achievements at this time were made in the cycle of paintings he called “Alogism” or “Transrational Realism.” Cow and Violin, Aviator, Englishman in Moscow, Portrait of Ivan Kliun—these works manifest a new method in the spatial organization of the painting, something unknown to the French Cub- ists. -

Marina Maximova Transformation of the Canon: Soviet Art Institutions, the Principles of Collecting and Institutionalisation of Contemporary Soviet Art

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 1 (2019) Marina Maximova Transformation of the Canon: Soviet Art Institutions, the Principles of Collecting and Institutionalisation of Contemporary Soviet Art ABSTRACT forward almost daily”. The article investigates these debates by analysing four museum strat- In 1987 the Moscow art scene became preoc- egies developed by various art practitioners cupied with the idea of establishing a museum and different criteria on the basis of which a of contemporary art. As Leonid Talochkin, an new canon for collecting contemporary art was active member of Moscow alternative artistic to be established. It suggests regarding those life, collector and archivist mentioned in his let- proposals in the contexts of social and political ter to one of his émigré artist-friends “everyone restructuring and openness introduced by Gor- seemed to have gone mad with all this museum bachev’s liberalisation. business” and “various proposals were put In 1987 the Moscow art scene became preoccupied with the idea of establishing a mu- seum of contemporary art. As Leonid Talochkin, an active member of Moscow alter- native artistic life, collector and archivist mentioned in a letter to one of his émigré artist-friends “everyone seemed to have gone mad with all this museum business” and “various proposals were put forward almost daily”. 1 What was the reason for such a sud- den surge of interest in collecting and the ambitions to introduce a new institution? By the late 1980s the Soviet Union had a wide network of museums of all kinds, includ- ing a significant share of collecting institutions devoted to art and culture. -

The Representation of American Visual Art in the USSR During the Cold War (1950S to the Late 1960S) by Kirill Chunikhin

The Representation of American Visual Art in the USSR during the Cold War (1950s to the late 1960s) by Kirill Chunikhin a Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Theory of Arts Approved Dissertation Committee _______________________________ Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche Jacobs University, Bremen Prof. Dr. Corinna Unger European University Institute, Florence Prof. Dr. Roman Grigoryev The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg Date of Defense: June 30, 2016 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. vii Statutory Declaration (on Authorship of a Dissertation) ........................................... ix List of Figures ............................................................................................................ x List of Attachments ................................................................................................. xiv Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 PART I. THE SOVIET APPROACH: MAKING AMERICAN ART ANTI- AMERICAN………………………………………………………………………………..11 Chapter 1. Introduction to the Totalitarian Art Discourse: Politics and Aesthetics in the Soviet Union ...................................................................................................... -

Model Exhibition*

Model Exhibition* MARIA GOUGH Despite the fact that it was never realized at full scale, Vladimir Tatlin’s long-lost model for his Monument to the Third International (1920) remains to this day the most widely known work of the Soviet avant-garde. A visionary proposal for a four-hundred-meter tower in iron and glass conceived at the height of the Russian Civil War, the monument was to house the headquarters of the Third International, or Comintern, the international organization of Communist, socialist, and other left-wing parties and workers’ organizations founded in Moscow in the wake of the October Revolution with the objective of fomenting revolutionary agitation abroad. Constructed in his spacious Petrograd studio, which was once the mosaics workshop of the imperial Academy of Art, Tatlin’s approximately 1:80 scale model comprises a skeletal wooden armature of two upward-moving spirals and a massive diagonal girder, within which are stacked four revolving geometrical volumes made out of paper, these last set in motion by means of a rotary crank located underneath the display platform. In the pro - posed monument-building, these volumes were to contain the Comintern’s legislature, executive branch, press bureau, and radio station. According to the later recollection of Tevel’ Schapiro, who assisted Tatlin in his construction of the model, two large arch spans at ground level were designed so that the tower could straddle the banks of the river Neva in Petrograd, the birthplace of the 1917 revolutions. Lost since the mid-1920s, Tatlin’s original model has been reconstructed sev - eral times at the behest of exhibition curators. -

Conflict Over Designing a Monument to Stalin's Victims : Public Art and Political Ideology in Russia, 1987-9 6

TITLE : PUBLIC ART AND POLITICAL IDEOLOGY IN RUSSIA. 1987-96 : CONFLICT OVER DESIGNING A MONUMENT TO STALIN'S VICTIM S AUTHOR : KATHLEEN E. SMITH, Hamilton College THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 INFORMATIONPROJECT :1 CONTRACTOR : Hamilton College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Kathleen E . Smit h COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1 -04 DATE : September 12, 199 6 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from researc h funded by contract with the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use : (2) fo r further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes : and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government . Neither the Council, nor the United States Government, nor any recipient of this Report by reason of such dissemination, may use this Report for commercial sale . 1 The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the Nationa l Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U . -

The Influence of the Vienna School of Art History on Soviet and Post-Soviet Historiography: Bruegel’S Case

The influence of the Vienna School of Art History on Soviet and post-Soviet historiography: Bruegel’s case Stefaniia Demchuk Introduction Soviet art historiography has remained a terra incognita for Western scholars for decades. Just a few names succeeded in breaking through the Iron Curtain. Mikhail Alpatov, Boris Vipper and Viktor Lazarev were among this lucky few.1 Although these sparks of recognition, if not sympathy, were insufficient to expose the theoretical or/and ideological underpinnings of Soviet art history. Today’s knowledge of the Soviet and post-Soviet realm is marked by deep- rooted misinterpretations and simplifications. Scholars addressing the Soviet art historical legacy deal with several tropes. Lithuanian-born American art historian Meyer Shapiro in his paper of 1936 scrutinizing ‘the New Viennese School’ had laid foundations for the first one that highlighted Russian/Soviet intellectual unity with the so-called New Vienna School through the personality of Mikhail Alpatov. 2 At 1 Translations made during the Soviet times from Soviet scholars’ works include but not limited to: Mikhail Alpatov, Nikolai Brunov Geschichte der Altrussischen Kunst : Textband, Augsburg: B. Filser Verl., 1932; Mikhail Alpatov, Russian impact on art, New York, Greenwood Press, 1950; [Trésors de l'art russe.] Art treasures of Russia, by M.W. Alpatov: notes on the plates by Olga Dacenko, translated by Norbert Guterman, London : Thames & Hudson, 1968; Mikhail Alpatov, Leonid Matsulevich, Freski tserkvi Uspeniia na Volotovom Pole, Moskva: Iskusstvo, 1977; Boris Vipper, Baroque art in Latvia, Riga, Valtera un Rapas, 1939; Boris Vipper, L'art letton: essai de synthèse historique, Riga : Izdevnieciba Tale, 1940; Viktor Lazarev, URSS icones anciennes de Russie, Paris: New York Graphic Society en accord avec l'UNESCO, 1958.