Art of the Commune and the Quest for a New Art in Post-Revolutionary Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 January 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Harding, J. (2015) 'European Avant-Garde coteries and the Modernist Magazine.', Modernism/modernity., 22 (4). pp. 811-820. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2015 by Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modernism/modernity 22:4 (2015), 811-820. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine Jason Harding Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2015, pp. 811-820 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605720 Access provided by Durham University (24 Jan 2017 12:36 GMT) Review Essay European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine By Jason Harding, Durham University MODERNISM / modernity The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist VOLUME TWENTY TWO, Magazines: Volume III, Europe 1880–1940. -

Becoming Tools for Artistic Consciousness of the People

34 commentary peer-reviewed article 35 that existed in the time of the Russian of the transformations in the urban space contents Revolution and those political events that of an early Soviet city. By using the dys- 33 Introduction, Irina Seits & Ekaterina influenced its destiny and to reflect on topian image of Mickey Mouse as the de- Kalinina the reforms in media, literature, urban sired inhabitant of modernity introduced peer-reviewed articles space and aesthetics that Russia was go- by Benjamin in “Experience and Poverty” 35 Becoming tools for artistic ing through in the post-revolutionary Seits provides an allegorical and com- consciousness of the people. decades. parative interpretation of the substantial The higher art school and changes in the living space of Moscow independent arts studios Overview of that were witnessed by Benjamin. in Petrograd (1918–1921), the contributions Mikhail Evsevyev Mikhail Evsevyev opens this issue with TORA LANE CONTRIBUTES in this issue with 45 Revolutionary synchrony: an analysis of the reorganization of the her reading of Viktor Pelevin’s Chapaev i A Day of the World, Robert Bird Higher Artistic School that was initiated Pustota (transl. as Buddha’s Little Finger or 53 Mickey Mouse – the perfect immediately after the Bolshevik Revolu- Clay Machine Gun), by situating her analy- tenant of an early Soviet city, tion in order to make art education ac- ses within the contemporary debates on Irina Seits cessible to the masses and to promote art realism and simulacra. She claims that Becoming 63 The inverted myth. Viktor as an important tool for the social trans- Pelevin, in his story about the period of Pelevin’s Buddhas little finger, formations in the Soviet state. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Download File

Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anita Tárnai All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai From 1914 to 1940 Russia lived through a series of traumatic events: World War I, the Bolshevik revolution, the Civil War, famine, and the Bolshevik and subsequently Stalinist terror. These events precipitated and facilitated a complete breakdown of the status quo associated with the tsarist regime and led to the emergence and eventual pervasive presence of a culture of violence propagated by the Bolshevik regime. This dissertation explores how the ongoing exposure to trauma impaired ordinary perception and everyday language use, which, in turn, informed literary language use in the writings of Viktor Shklovsky, the prominent Formalist theoretician, and of the avant-garde writer, Daniil Kharms. While trauma studies usually focus on the reconstructive and redeeming features of trauma narratives, I invite readers to explore the structural features of literary language and how these features parallel mechanisms of cognitive processing, established by medical research, that take place in the mind affected by traumatic encounters. Central to my analysis are Shklovsky’s memoir A Sentimental Journey and his early articles on the theory of prose “Art as Device” and “The Relationship between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style” and Daniil Karms’s theoretical writings on the concepts of “nothingness,” “circle,” and “zero,” and his prose work written in the 1930s. -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

Aleksandra Khokhlova

Aleksandra Khokhlova Also Known As: Aleksandra Sergeevna Khokhlova, Aleksandra Botkina Lived: November 4, 1897 - August 22, 1985 Worked as: acting teacher, assistant director, co-director, directing teacher, director, film actress, writer Worked In: Russia by Ana Olenina Today Aleksandra Khokhlova is remembered as the star actress in films directed by Lev Kuleshov in the 1920s and 1930s. Indeed, at the peak of her career she was at the epicenter of the Soviet avant-garde, an icon of the experimental acting that matched the style of revolutionary montage cinema. Looking back at his life, Kuleshov wrote: “Nearly all that I have done in film directing, in teaching, and in life is connected to her [Khokhlova] in terms of ideas and art practice” (1946, 162). Yet, Khokhlova was much more than Kuleshov’s wife and muse as in her own right she was a talented author, actress, and film director, an artist in formation long before she met Kuleshov. Growing up in an affluent intellectual family, Aleksandra would have had many inspiring artistic encounters. Her maternal grandfather, the merchant Pavel Tretyakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was a philanthropist and patron who purchased and exhibited masterpieces of Russian Romanticism, Realism, and Symbolism. Aleksandra’s parents’ St. Petersburg home was a prestigious art salon and significant painters, actors, and musicians were family friends. Portraits of Aleksandra as a young girl were painted by such eminent artists as Valentin Serov and Filipp Maliavin. Aleksandra’s father, the doctor Sergei Botkin, an art connoisseur and collector, cultivated ties to the World of Arts circle–the creators of the Ballets Russes. -

Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 39 (# 21) Year 2018. Page 18 Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia Problemas para mejorar la calidad de la enseñanza de las Bellas Artes en la Escuela de Educación General en la Rusia moderna Elena S. MEDKOVA 1 Received: 12/01/2018 • Approved: 06/02/2018 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods 3. Results 4. Discussion 5. Conclusion Acknowledgements References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article considers topical problems of teaching fine El artículo considera los problemas actuales de la arts in general education school of modern Russia on enseñanza de las bellas artes en la escuela de the basis of mastering models of artistic thinking educación general de la Rusia moderna sobre la base based on the achievements of modern and de dominar los modelos de pensamiento artístico contemporary art. The author gives a detailed basados en los logros del arte moderno y historical digression of the contradictory history of the contemporáneo. El autor ofrece una digresión introduction of avant-garde ideas into the educational histórica detallada de la historia contradictoria de la process of higher school and general education introducción de ideas vanguardistas en el proceso schools throughout the 20th century in Russia. The educativo de las escuelas de educación superior y article presents the materials of the research of the educación general a lo largo del siglo XX en Rusia. El modern state of teaching fine arts in school. It artículo presenta los materiales de la investigación del analyzes the content of the most popular textbooks estado moderno de la enseñanza de las bellas artes on fine arts from the positions of balance in their en la escuela. -

Serge Diaghilev's Art Journal

Mir iskus8tva, SERGE DIAGHILEV'S ART JOURNAL As part of a project to celebrate Seriozha, and sometimes, in later years, to the three tours to Australia by the dancers who worked for him, as Big Serge. Reputedly he was of only medium height Ballets Russes companies between but he had wide shoulders and a large head 1936 and 1940, Michelle Potter (many of his contemporaries made this looks at a seminal fin de siecle art observation). But more than anything, he journal conceived by Serge Diaghilev had big ideas and grand attitudes. When he wrote to his artist friend, Alexander Benois, that he saw the future through a magnifying 'In a word I see the future through a glass, he could have been referring to any magnifying glass'. of his endeavours in the arts. Or even to - Serge Diaghilev, 1897 his extreme obsessions, such as his fear of dying on water and his consequent erge Diaghilev, Russian impresario deep reluctance to travel anywhere by extraordinaire, was an imposing person. boat. But in fact, in this instance, he was SPerhaps best remembered as the man referring specifically to his vision for the behind the Ballets Russes,the legendary establishment of an art journal. dance company that took Paris by storm in This remarkable journal, Mir iskusstva 1909, he was known to his inner circle as (World of Art). which went into production dance had generated a catalogue search on Diaghilev, which uncovered the record. With some degree of excitement, staff called in the journals from offsite storage. Research revealed that the collection was indeed a full run. -

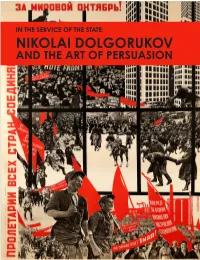

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

1. Coversheet Thesis

Eleanor Rees The Kino-Khudozhnik and the Material Environment in Early Russian and Soviet Fiction Cinema, c. 1907-1930. January 2020 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London Supervisors: Dr. Rachel Morley and Dr. Philip Cavendish !1 I, Eleanor Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Word Count: 94,990 (including footnotes and references, but excluding contents, abstract, impact statement, acknowledgements, filmography and bibliography). ELEANOR REES 2 Contents Abstract 5 Impact Statement 6 Acknowledgments 8 Note on Transliteration and Translation 10 List of Illustrations 11 Introduction 17 I. Aims II. Literature Review III. Approach and Scope IV. Thesis Structure Chapter One: Early Russian and Soviet Kino-khudozhniki: 35 Professional Backgrounds and Working Practices I. The Artistic Training and Pre-cinema Affiliations of Kino-khudozhniki II. Kino-khudozhniki and the Russian and Soviet Studio System III. Collaborative Relationships IV. Roles and Responsibilities Chapter Two: The Rural Environment 74 I. Authenticity, the Russian Landscape and the Search for a Native Cinema II. Ethnographic and Psychological Realism III. Transforming the Rural Environment: The Enchantment of Infrastructure and Technology in Early-Soviet Fiction Films IV. Conclusion Chapter Three: The Domestic Interior 114 I. The House as Entrapment: The Domestic Interiors of Boris Mikhin and Evgenii Bauer II. The House as Ornament: Excess and Visual Expressivity III. The House as Shelter: Representations of Material and Psychological Comfort in 1920s Soviet Cinema IV. -

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century Elena S. Stetskevich The early days of the Academy The Russian Academy of Sciences was founded in 1724.1 During the first half of the eighteenth century, it was the unique scientific, educational, artistic and publishing center in Russia. The Academy consisted of different parts, including the first Russian university, a secondary school (“gymnasium”), library, public museum (Кунсткамера/ “Kunstkamera”), astronomical observatory and anatomical theater. The wide range of tasks of the Academy included the development of natural sciences and humanities, teaching of youth in science and dissemination of knowledge in the country. Along with the cultivation of sciences, the Academy was also planned to organize the training of artistic disciplines.2 The draft regulation from 1725, which was not approved, witnesses the fixed intention to open an Academy of Arts within the Academy of Sciences. It was assumed that the Academy of Arts could be used to teach those students who express the desire to learn artistic practices, as well as those who were unable to study at a gymna- sium.3 However, this intention was not implemented, as the founder of the Academy of Sciences – Tsar Peter the Great (1682–1725) – died before he could approve the regulation. However, drawing education was included in the program of the academic gym- nasium as a mandatory subject. It was taught one hour a day, four times a week, in the afternoon.4 Originally, these lessons were conducted by artists who were members of 1 The ‘Russian Academy of Sciences’ had different names in the first half of the eighteenth century, including ‘The Academy of Arts and Sciences’ and the ‘Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts in St.