Ellis H. Minns and Nikodim Kondakov's the Russian Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Tools for Artistic Consciousness of the People

34 commentary peer-reviewed article 35 that existed in the time of the Russian of the transformations in the urban space contents Revolution and those political events that of an early Soviet city. By using the dys- 33 Introduction, Irina Seits & Ekaterina influenced its destiny and to reflect on topian image of Mickey Mouse as the de- Kalinina the reforms in media, literature, urban sired inhabitant of modernity introduced peer-reviewed articles space and aesthetics that Russia was go- by Benjamin in “Experience and Poverty” 35 Becoming tools for artistic ing through in the post-revolutionary Seits provides an allegorical and com- consciousness of the people. decades. parative interpretation of the substantial The higher art school and changes in the living space of Moscow independent arts studios Overview of that were witnessed by Benjamin. in Petrograd (1918–1921), the contributions Mikhail Evsevyev Mikhail Evsevyev opens this issue with TORA LANE CONTRIBUTES in this issue with 45 Revolutionary synchrony: an analysis of the reorganization of the her reading of Viktor Pelevin’s Chapaev i A Day of the World, Robert Bird Higher Artistic School that was initiated Pustota (transl. as Buddha’s Little Finger or 53 Mickey Mouse – the perfect immediately after the Bolshevik Revolu- Clay Machine Gun), by situating her analy- tenant of an early Soviet city, tion in order to make art education ac- ses within the contemporary debates on Irina Seits cessible to the masses and to promote art realism and simulacra. She claims that Becoming 63 The inverted myth. Viktor as an important tool for the social trans- Pelevin, in his story about the period of Pelevin’s Buddhas little finger, formations in the Soviet state. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Thomas De Simone, B.A., M.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Nicholas Breyfogle, Advisor David Hoffmann Robin Judd Predrag Matejic Copyright by Peter T. De Simone 2012 Abstract In the mid-seventeenth century Nikon, Patriarch of Moscow, introduced a number of reforms to bring the Russian Orthodox Church into ritualistic and liturgical conformity with the Greek Orthodox Church. However, Nikon‘s reforms met staunch resistance from a number of clergy, led by figures such as the archpriest Avvakum and Bishop Pavel of Kolomna, as well as large portions of the general Russian population. Nikon‘s critics rejected the reforms on two key principles: that conformity with the Greek Church corrupted Russian Orthodoxy‘s spiritual purity and negated Russia‘s historical and Christian destiny as the Third Rome – the final capital of all Christendom before the End Times. Developed in the early sixteenth century, what became the Third Rome Doctrine proclaimed that Muscovite Russia inherited the political and spiritual legacy of the Roman Empire as passed from Constantinople. In the mind of Nikon‘s critics, the Doctrine proclaimed that Constantinople fell in 1453 due to God‘s displeasure with the Greeks. Therefore, to Nikon‘s critics introducing Greek rituals and liturgical reform was to invite the same heresies that led to the Greeks‘ downfall. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Supplementum 2020/1

Exchanges and Interactions in the Arts of Medieval Europe, Byzantium, and the Mediterranean Seminarium Kondakovianum, Series Nova Université de Lausanne • Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic • Masaryk University • C CONVIVIUM SUPPLEMENTUM 2020 Exchanges and Interactions in the Arts of Medieval Europe, Byzantium, and the Mediterranean Seminarium Kondakovianum, Series Nova Journal of the Department of Art History of the University of Lausanne, of the Department of Art History of the Masaryk University, and of the Institute of Art History of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic This supplementary issue was carried out as part of the project “The Heritage of Nikodim Pavlovič Kondakov in the Experiences of André Grabar and the Seminarium Kondakovianum” (Czech Science Foundation, Reg. No 18 –20666S) Editor-in-chief / Ivan Foletti Executive editors / Karolina Foletti, Sarah Melker, Adrien Palladino, Johanna Zacharias Typesetting / Kristýna Smrčková Layout design / Monika Kučerová Cover design / Petr M. Vronský, Anna Kelblová Publisher / Masarykova univerzita, Žerotínovo nám. 9, 601 77 Brno, IČO 00216224 Editorial Office / Seminář dějin umění, Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity, Arna Nováka 1, 602 00 Brno Print / Tiskárna Didot, spol s r.o., Trnkova 119, 628 00 Brno E-mail / [email protected] www.earlymedievalstudies.com/convivium.html © Ústav dějin umění AV ČR , v. v. i. 2020 © Filozofická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity 2020 © Faculté des Lettres, Université de Lausanne 2020 Published / November 2020 Reg. No. MK ČR E 21592 ISSN 2336-3452 (print) ISSN 2336-808X (online) ISBN 978-80-210-9709-4 Convivium is listed in the databases SCOPUS, ERIH, “Riviste di classe A” indexed by ANVUR, and in the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) of the Web of Science. -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 39 (# 21) Year 2018. Page 18 Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia Problemas para mejorar la calidad de la enseñanza de las Bellas Artes en la Escuela de Educación General en la Rusia moderna Elena S. MEDKOVA 1 Received: 12/01/2018 • Approved: 06/02/2018 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods 3. Results 4. Discussion 5. Conclusion Acknowledgements References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article considers topical problems of teaching fine El artículo considera los problemas actuales de la arts in general education school of modern Russia on enseñanza de las bellas artes en la escuela de the basis of mastering models of artistic thinking educación general de la Rusia moderna sobre la base based on the achievements of modern and de dominar los modelos de pensamiento artístico contemporary art. The author gives a detailed basados en los logros del arte moderno y historical digression of the contradictory history of the contemporáneo. El autor ofrece una digresión introduction of avant-garde ideas into the educational histórica detallada de la historia contradictoria de la process of higher school and general education introducción de ideas vanguardistas en el proceso schools throughout the 20th century in Russia. The educativo de las escuelas de educación superior y article presents the materials of the research of the educación general a lo largo del siglo XX en Rusia. El modern state of teaching fine arts in school. It artículo presenta los materiales de la investigación del analyzes the content of the most popular textbooks estado moderno de la enseñanza de las bellas artes on fine arts from the positions of balance in their en la escuela. -

Serge Diaghilev's Art Journal

Mir iskus8tva, SERGE DIAGHILEV'S ART JOURNAL As part of a project to celebrate Seriozha, and sometimes, in later years, to the three tours to Australia by the dancers who worked for him, as Big Serge. Reputedly he was of only medium height Ballets Russes companies between but he had wide shoulders and a large head 1936 and 1940, Michelle Potter (many of his contemporaries made this looks at a seminal fin de siecle art observation). But more than anything, he journal conceived by Serge Diaghilev had big ideas and grand attitudes. When he wrote to his artist friend, Alexander Benois, that he saw the future through a magnifying 'In a word I see the future through a glass, he could have been referring to any magnifying glass'. of his endeavours in the arts. Or even to - Serge Diaghilev, 1897 his extreme obsessions, such as his fear of dying on water and his consequent erge Diaghilev, Russian impresario deep reluctance to travel anywhere by extraordinaire, was an imposing person. boat. But in fact, in this instance, he was SPerhaps best remembered as the man referring specifically to his vision for the behind the Ballets Russes,the legendary establishment of an art journal. dance company that took Paris by storm in This remarkable journal, Mir iskusstva 1909, he was known to his inner circle as (World of Art). which went into production dance had generated a catalogue search on Diaghilev, which uncovered the record. With some degree of excitement, staff called in the journals from offsite storage. Research revealed that the collection was indeed a full run. -

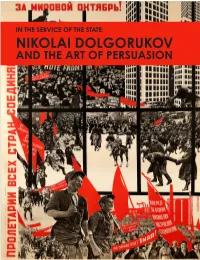

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

The Russian Orthodox Church As Reflected in Orthodox and Atheist Publications in the Soviet Union

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 3 Issue 2 Article 2 2-1983 The Russian Orthodox Church as Reflected in Orthodox and Atheist Publications in the Soviet Union Alf Johansen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johansen, Alf (1983) "The Russian Orthodox Church as Reflected in Orthodox and Atheist Publications in the Soviet Union," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol3/iss2/2 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AS REFLECTED IN ORTHODOX AND ATHEIST PUBLICATIONS IN THE SOVIET UNION By Alf Johansen Alf Johansen , a Lutheran pastor from Logstor, Denmark, is a specialist on the Orthodox Churches . He wrote the article on the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in OPREE Vol . 1, No . 7 (December , 1981). He wrote a book on the Russian Orthodox Church in Danish in 1950, and one entitled Theological Study in the Russian and Bulgarian Orthodox Churches under Communist Rule (London : The Faith Press, 1963). In addition he has written a few articles on Romanian , Russian , and Bulgarian Orthodox Churches in the Journal of Ecumenical Studies as well as articles in Diakonia. He has worked extensively with the typescripts of licentiates ' and masters ' theses of Russian Orthodox authors , una va ilable to the general public. -

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Harsha Ram, Chair Professor Irina Paperno Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2010 ABSTRACT Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Harsha Ram, Chair The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 reminded many that “Soviet” and “Russian” were not synonymous, but this distinction continues to be overlooked when discussing Soviet literature. Like the Soviet Union, Soviet literature was a consciously multinational, multiethnic project. This dissertation approaches Soviet literature in its broadest sense – as a cultural field incorporating texts, institutions, theories, and practices such as writing, editing, reading, canonization, education, performance, and translation. It uses archival materials to analyze how Soviet literary institutions combined Russia’s literary heritage, the doctrine of socialist realism, and nationalities policy to conceptualize the national literatures, a term used to define the literatures of the non-Russian peripheries. It then explores how such conceptions functioned in practice in the early 1930s, in both Moscow and Baku, the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan. Although the debates over national literatures started well before the Revolution, this study focuses on 1932-34 as the period when they crystallized under the leadership of the Union of Soviet Writers. -

![Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 53/4 | 2012 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Décembre 2013, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6562/cahiers-du-monde-russe-53-4-2012-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-d%C3%A9cembre-2013-consult%C3%A9-le-23-septembre-2020-2096562.webp)

Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 53/4 | 2012 [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Décembre 2013, Consulté Le 23 Septembre 2020

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 53/4 | 2012 Varia Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/7690 DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.7690 ISSN : 1777-5388 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 décembre 2012 ISSN : 1252-6576 Référence électronique Cahiers du monde russe, 53/4 | 2012 [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2013, Consulté le 23 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/7690 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/monderusse.7690 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 23 septembre 2020. © École des hautes études en sciences sociales 1 SOMMAIRE Articles Государственные институты и гражданские добродетели в политической мысли Н.И. Панина (60 – 80-е гг. XVIII в.) Константин Д. Бугров Témoignages et œuvres littéraires sur le massacre de Babij Jar, 1941-1948 Boris Czerny Une philosophie dans les marges Le cas du conceptualisme moscovite Emanuel Landolt et Michail Maiatsky • • • Comptes rendus • • • Russie ancienne et impériale Pierre Gonneau, Aleksandr Lavrov, Des Rhôs à la Russie Marie-Karine Schaub A. Miller, D. Svizhkov and I. Schierle, éds. , « Poniatija o Rossii » Richard Wortman Brian L. Davies, ed., Warfare in Eastern Europe André Berelowitch David Moon, The Plough that Broke the Steppe Alessandro Stanziani Matthew P. Romaniello, The Elusive Empire Mikhail Krom Robert O. Crummey, Old Believers in a Changing World Aleksandr Lavrov Evgenij Akel´ev, Povsednevnaja žizn´ vorovskogo mira Moskvy vo vremena Van´ki Kaina David L. Ransel Catherine Evtuhov, Portrait of a Russian Province Olga E. Glagoleva Daniel´ Bovua [Daniel Beauvois], Gordiev Uzel Rossijskoj imperii Aleksej Miller Anton A.