Center 10 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1989-May 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

121022 Descendants of Konrad John Lautermilch

Konrad John Lautermilch and His American Descendants by Alice Marie Zoll and Maintained by Christopher Kerr (Last Revision: 22 October 2012) LAUTERMILCH means Whole-milk or All-milk Then God Said to Noah "Go forth from the Ark, you and your wife, and your sons and their wives....and be fruitful and multiply....". Genesis 8:17 Early Ancestors in Germany: Melchoir Lautermilch 1697-1775 His brothers and sisters: Magdalena Anna Lautermilch 1703 Came to U.S. 1731 Wendel George Lautermilch 1705 Came to U.S. 1731 Gottried Lautermilch 1708 Came to U.S. 1736 Anton (twin) Lautermilch 1708 Came to U.S. 1736 Jacob Lautermilch 1716 Melchoir's Son: Adam Hans Lautermilch 1754-1781 His brothers and sisters George John 1738-1833 Maria Anna 1736- Nicholas 1733- d. in Germany Adam Hans Lautermilch's Son: Konrad John Lautermilch 1776-1834 d. in Germany His Children: Johann Martin Germany Johanna Germany Conrad Jr U.S.A. Katherine Germany Dietrich Germany Welhelm U.S.A. Charles U.S.A. Carl Ernest Germany Margaret U.S.A. George Adam U.S.A. Alexander Euglina U.S.A. Daughter Germany Abbreviations used: A. Adopted b. born child. children bu. buried d. died co. county dau. daughter div. divorced M. Married occ. occupation Preface It was during the reign of Louis IX, the period when the Germanic Coumentites produced only poverty and death and the spirits of its people were at their lowest, that we find Konrad John Lautermilch married to Johanna Katherine Kopf. They were from Sinnsheim and Karchard. Kirchard and Sinnsheim are towns about 40 kilometers northeast of Kurhsruhe and 20 kilometers southeast of Heidelberg, Baden, Germany. -

Becoming Tools for Artistic Consciousness of the People

34 commentary peer-reviewed article 35 that existed in the time of the Russian of the transformations in the urban space contents Revolution and those political events that of an early Soviet city. By using the dys- 33 Introduction, Irina Seits & Ekaterina influenced its destiny and to reflect on topian image of Mickey Mouse as the de- Kalinina the reforms in media, literature, urban sired inhabitant of modernity introduced peer-reviewed articles space and aesthetics that Russia was go- by Benjamin in “Experience and Poverty” 35 Becoming tools for artistic ing through in the post-revolutionary Seits provides an allegorical and com- consciousness of the people. decades. parative interpretation of the substantial The higher art school and changes in the living space of Moscow independent arts studios Overview of that were witnessed by Benjamin. in Petrograd (1918–1921), the contributions Mikhail Evsevyev Mikhail Evsevyev opens this issue with TORA LANE CONTRIBUTES in this issue with 45 Revolutionary synchrony: an analysis of the reorganization of the her reading of Viktor Pelevin’s Chapaev i A Day of the World, Robert Bird Higher Artistic School that was initiated Pustota (transl. as Buddha’s Little Finger or 53 Mickey Mouse – the perfect immediately after the Bolshevik Revolu- Clay Machine Gun), by situating her analy- tenant of an early Soviet city, tion in order to make art education ac- ses within the contemporary debates on Irina Seits cessible to the masses and to promote art realism and simulacra. She claims that Becoming 63 The inverted myth. Viktor as an important tool for the social trans- Pelevin, in his story about the period of Pelevin’s Buddhas little finger, formations in the Soviet state. -

Studia Varia from the J

OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON ANTIQUITIES, 10 Studia Varia from the J. Paul Getty Museum Volume 2 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 2001 © 2001 The J. Paul Getty Trust Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www. getty. edu Christopher Hudson, Publisher Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Project staff: Editors: Marion True, Curator of Antiquities, and Mary Louise Hart, Assistant Curator of Antiquities Manuscript Editor: Bénédicte Gilman Production Coordinator: Elizabeth Chapin Kahn Design Coordinator: Kurt Hauser Photographers, photographs provided by the Getty Museum: Ellen Rosenbery and Lou Meluso. Unless otherwise noted, photographs were provided by the owners of the objects and are reproduced by permission of those owners. Typography, photo scans, and layout by Integrated Composition Systems, Inc. Printed by Science Press, Div. of the Mack Printing Group Cover: One of a pair of terra-cotta arulae. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 86.AD.598.1. See article by Gina Salapata, pp. 25-50. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Studia varia. p. cm.—-(Occasional papers on antiquities : 10) ISBN 0-89236-634-6: English, German, and Italian. i. Art objects, Classical. 2. Art objects:—California—Malibu. 3. J. Paul Getty Museum. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Series. NK665.S78 1993 709'.3 8^7479493—dc20 93-16382 CIP CONTENTS Coppe ioniche in argento i Pier Giovanni Guzzo Life and Death at the Hands of a Siren 7 Despoina Tsiafakis An Exceptional Pair of Terra-cotta Arulae from South Italy 25 Gina Salapata Images of Alexander the Great in the Getty Museum 51 Janet Burnett Grossman Hellenistisches Gold und ptolemaische Herrscher 79 Michael Pfrommer Two Bronze Portrait Busts of Slave Boys from a Shrine of Cobannus in Gaul 115 John Pollini Technical Investigation of a Painted Romano-Egyptian Sarcophagus from the Fourth Century A.D. -

Volume 92 (1988)

AMERICANJOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE JOURNAL OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA EDITORS FRED S. KLEINER,Editor-in-Chief TRACEY CULLEN, AssociateEditor MARGARET MILHOUS, EditorialAssistant STEPHEN L. DYSON, Editor,Book Reviews ADVISORY BOARD GEORGEF. BASS WILLIAM E. METCALF Texas A & M University The American Numismatic Society LARISSA BONFANTE JOHN P. OLESON New York University The University of Victoria DIANA BUITRON-OLIVER JEROMEJ. POLLITT Baltimore Society Yale University RICHARD D. DE PUMA EDITH PORADA The University of Iowa Columbia University WILLIAMB. DINSMOOR,JR. GEORGE RAPP, JR. American School of Classical Studies at Athens University of Minnesota, Duluth EVELYN B. HARRISON L. RICHARDSON,JR New York University Duke University R. Ross HOLLOWAY JEREMY B. RUTTER Brown University Dartmouth College DIANA E.E. KLEINER JOSEPH W. SHAW Yale University University of Toronto MACHTELD J. MELLINK RONALD S. STROUD Bryn Mawr College University of California, Berkeley PETER S. WELLS University of Minnesota, Twin Cities ex officio JAMES R. WISEMAN LAWRENCE E. STAGER Boston University Harvard University I -VO X VI MEN p RVM PTA 0,PRIO ~P af'INCO o RV THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY,the Journal of the ArchaeologicalInstitute of America, was founded in 1885; the second series was begun in 1897. Indexes have been published for volumes 1-11 (1885-1896), for the second series, volumes 1-10 (1897-1906) and volumes 11-70 (1907-1966). The Journal is indexed in the Social Sciencesand Humanities Index, the ABS International Guide to Classical Studies, Current Contents, the Book Review Index, the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals,and BRISSP. MANUSCRIPTS and all communications for the editors should be addressed to Professor Fred S. -

Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 39 (# 21) Year 2018. Page 18 Problems of Improving the Quality of Teaching Fine Arts in General Education School in Modern Russia Problemas para mejorar la calidad de la enseñanza de las Bellas Artes en la Escuela de Educación General en la Rusia moderna Elena S. MEDKOVA 1 Received: 12/01/2018 • Approved: 06/02/2018 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods 3. Results 4. Discussion 5. Conclusion Acknowledgements References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article considers topical problems of teaching fine El artículo considera los problemas actuales de la arts in general education school of modern Russia on enseñanza de las bellas artes en la escuela de the basis of mastering models of artistic thinking educación general de la Rusia moderna sobre la base based on the achievements of modern and de dominar los modelos de pensamiento artístico contemporary art. The author gives a detailed basados en los logros del arte moderno y historical digression of the contradictory history of the contemporáneo. El autor ofrece una digresión introduction of avant-garde ideas into the educational histórica detallada de la historia contradictoria de la process of higher school and general education introducción de ideas vanguardistas en el proceso schools throughout the 20th century in Russia. The educativo de las escuelas de educación superior y article presents the materials of the research of the educación general a lo largo del siglo XX en Rusia. El modern state of teaching fine arts in school. It artículo presenta los materiales de la investigación del analyzes the content of the most popular textbooks estado moderno de la enseñanza de las bellas artes on fine arts from the positions of balance in their en la escuela. -

Serge Diaghilev's Art Journal

Mir iskus8tva, SERGE DIAGHILEV'S ART JOURNAL As part of a project to celebrate Seriozha, and sometimes, in later years, to the three tours to Australia by the dancers who worked for him, as Big Serge. Reputedly he was of only medium height Ballets Russes companies between but he had wide shoulders and a large head 1936 and 1940, Michelle Potter (many of his contemporaries made this looks at a seminal fin de siecle art observation). But more than anything, he journal conceived by Serge Diaghilev had big ideas and grand attitudes. When he wrote to his artist friend, Alexander Benois, that he saw the future through a magnifying 'In a word I see the future through a glass, he could have been referring to any magnifying glass'. of his endeavours in the arts. Or even to - Serge Diaghilev, 1897 his extreme obsessions, such as his fear of dying on water and his consequent erge Diaghilev, Russian impresario deep reluctance to travel anywhere by extraordinaire, was an imposing person. boat. But in fact, in this instance, he was SPerhaps best remembered as the man referring specifically to his vision for the behind the Ballets Russes,the legendary establishment of an art journal. dance company that took Paris by storm in This remarkable journal, Mir iskusstva 1909, he was known to his inner circle as (World of Art). which went into production dance had generated a catalogue search on Diaghilev, which uncovered the record. With some degree of excitement, staff called in the journals from offsite storage. Research revealed that the collection was indeed a full run. -

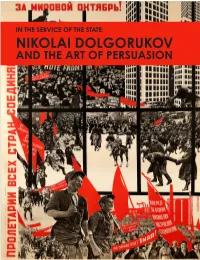

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

CHG Library Book List

CHG Library Book List (Belgium), M. r. d. a. e. d. h. (1967). Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire, Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'art et dʹhistoire, Parc du Cinquantenaire, 1967. Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire by Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire (Belgium) (1967) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (January, 1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5 by Thomas P.F. Hoving (1968) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1973). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXXI, Number 3. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.), A. B. S. (2002). Persephone. U.S.A/ Cambridge, President and Fellows of Harvard College Puritan Press, Inc. (Ed.), A. D. (2005). From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830. /Benaki Museum. Athens, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. (Ed.), B. B. R. (2000). Christian VIII: The National Museum: Antiquities, Coins, Medals. Copenhagen, The National Museum of Denmark. (Ed.), J. I. (1999). Interviews with Ali Pacha of Joanina; in the autumn of 1812; with some particulars of Epirus, and the Albanians of the present day (Peter Oluf Brondsted). Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens. (Ed.), K. D. (1988). Antalya Museum. İstanbul, T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Döner Sermaye İşletmeleri Merkez Müdürlüğü/ Ankara. (ed.), M. N. B. (Ocak- Nisan 2010). "Arkeoloji ve sanat. (Journal of Archaeology and Art): Ölümünün 100.Yıldönümünde Osman Hamdi Bey ve Kazıları." Arkeoloji Ve Sanat 133. -

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century

Drawing Education at the Russian Academy of Sciences in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century Elena S. Stetskevich The early days of the Academy The Russian Academy of Sciences was founded in 1724.1 During the first half of the eighteenth century, it was the unique scientific, educational, artistic and publishing center in Russia. The Academy consisted of different parts, including the first Russian university, a secondary school (“gymnasium”), library, public museum (Кунсткамера/ “Kunstkamera”), astronomical observatory and anatomical theater. The wide range of tasks of the Academy included the development of natural sciences and humanities, teaching of youth in science and dissemination of knowledge in the country. Along with the cultivation of sciences, the Academy was also planned to organize the training of artistic disciplines.2 The draft regulation from 1725, which was not approved, witnesses the fixed intention to open an Academy of Arts within the Academy of Sciences. It was assumed that the Academy of Arts could be used to teach those students who express the desire to learn artistic practices, as well as those who were unable to study at a gymna- sium.3 However, this intention was not implemented, as the founder of the Academy of Sciences – Tsar Peter the Great (1682–1725) – died before he could approve the regulation. However, drawing education was included in the program of the academic gym- nasium as a mandatory subject. It was taught one hour a day, four times a week, in the afternoon.4 Originally, these lessons were conducted by artists who were members of 1 The ‘Russian Academy of Sciences’ had different names in the first half of the eighteenth century, including ‘The Academy of Arts and Sciences’ and the ‘Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts in St. -

Aicher, PJ, Guide to the Aqueducts of Ancient Rome., Wauconda, Amici, C

352 List of Works Cited. ! . Aicher, P. J., Guide to the Aqueducts of Ancient Rome., Wauconda, 1995. Alfoldy, G., "Eine Bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum.", ZPE 109, 1995, pp. 195-226. Amici, c., II Foro di Traiano; Basilica Ulpia e Biblioteche, Rome, 1982. Amici, C. M., II foro di Cesare., Florence, 1991. Ammerman, A. J., IOn the Origins of the Forum Romanum', AlA 94, 1990, pp. 627-45. Anderson Jr., J. c. 1 IDomitian/s Building Programme. Forum Julium and markets of Trajan.', ArchN 10, 1981, pp. 41-8. Anderson Jr., J. c., I A Topographical tradition in Fourth Century Chronicles: Domitian' Building Program/, Historia 32, 1983, pp. 93-105. Anderson, Jr., J. c., Historical Topography of the Imperial Fora, Brussels, 1984. Anderson Jr., J. c., 'The Date of the Thermae Traianae and the Topography of the Oppius Mons/,AlA 89, 1985, pp. 499-509. Anderson Jr., J. c., IIDomitian, the Argiletum and the Temple of Peace/, AlA 86, 1992, pp. 101-18. Anderson Jr, J. c., Roman Architecture and Society, Baltimore, 1997. Ashby, T., The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome., Oxford, 1935. I j 353 Ball, L. F., I A reappraisal of Nero's Domus Aurea., JRA Supp. 11, Ann Arbor, 1994, pp. 183-254. Balland, A., 'La casa Romuli au Palatin et au Capitole!, REL 62, 1984, pp.57-80. Balsdon, J. P. V. D., The Emperor Gaius (Caligula)., Oxford, 1934. Barattolo, A., 'Nuove ricerche sull' architettura del Tempio di Venere 11 e di Roma in eta Adriana.', MDAI 80, 1973, pp. 243-69. Barattolo, A., 'II Tempio di Venere e Roma: un tempio 'greco' nell' Urbe.', MDAI 85,1978, pp. -

La Regia, Le Rex Sacrorum Et La Res Publica Michel Humm

La Regia, le rex sacrorum et la Res publica Michel Humm To cite this version: Michel Humm. La Regia, le rex sacrorum et la Res publica. Archimède : archéologie et histoire ancienne, UMR7044 - Archimède, 2017, pp.129-154. halshs-01589194 HAL Id: halshs-01589194 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01589194 Submitted on 18 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARCHIMÈDE N°4 ARCHÉOLOGIE ET HISTOIRE ANCIENNE 2017 1 DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE 1 : NOMMER LES « ORIENTAUX » DANS L’ANTIQUITÉ DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE 2 : PRYTANÉE ET REGIA Michel HUMM 87 Introduction. Prytanée et Regia : demeures « royales » ou sanctuaires civiques ? Athènes, Rome et la « médiation » étrusque Patrick MARCHETTI 94 Les prytanées d’Athènes Dominique BRIQUEL 110 Les monuments de type Regia dans le monde étrusque, Murlo et Acquarossa Michel HUMM 129 La Regia, le rex sacrorum et la Res publica 155 ACTUALITÉ DE LA RECHERCHE : DYNAMIQUES HUMAINES ANCIENNES 216 VARIA 236 LA CHRONIQUE D’ARCHIMÈDE Retrouvez tous les articles de la revue ARCHIMÈDE sur http://archimede.unistra.fr/revue-archimede/