Blanche of Castile: Queen of France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eleanor and the Angevin Empire

Eleanor and the Angevin Empire History Lesson 2 of an enquiry of 4 lessons Enquiry: What can the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine tell us about who held power in the Middle Ages? Ms Barnett Mr Arscott 1152 Eleanor’s marriage to King Louis VII of France ended in 1152. Once the couple had separated Eleanor returned to Aquitaine to rule as Duchess. Aged 28, Eleanor once again became a desired bride in Europe. She was single, young enough to have more children and in charge of a powerful and rich area of southern France. Eleanor was so desirable as a bride that two men tried to kidnap her on her journey from Paris to Aquitaine. Eleanor managed to avoid capture. Instead she focused on entering into marriage in a more traditional way. 8 weeks and 2 days after her separation from Louis, Eleanor married once again. Eleanor and Henry Eleanor’s second husband was 19 year old Henry. He was Duke of Normandy as well as the Count of Anjou and Maine. This marriage was controversial at the time. Firstly Henry was 9 years younger than Eleanor. Traditionally in the Middle Ages older men married younger women, not the other way round! Also, Eleanor’s second marriage happened only 8 weeks after her separation from King Louis. A chronicle from the time said that Eleanor and Henry married “without the pomp and ceremony that befitted their rank.” It wasn’t a big ceremony and didn’t reflect their wealth and importance. Why was this wedding arranged so quickly? Increased territories It is possible the wedding took place quickly because Henry was seen as a controversial choice. -

Eleanor of Aquitaine and 12Th Century Anglo-Norman Literary Milieu

THE QUEEN OF TROUBADOURS GOES TO ENGLAND: ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE AND 12TH CENTURY ANGLO-NORMAN LITERARY MILIEU EUGENIO M. OLIVARES MERINO Universidad de Jaén The purpose of the present paper is to cast some light on the role played by Eleanor of Aquitaine in the development of Anglo-Norman literature at the time when she was Queen of England (1155-1204). Although her importance in the growth of courtly love literature in France has been sufficiently stated, little attention has been paid to her patronising activities in England. My contribution provides a new portrait of the Queen of Troubadours, also as a promoter of Anglo-Norman literature: many were the authors, both French and English, who might have written under her royal patronage during the second half of the 12th century. Starting with Rita Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on the Queen’s literary role, I have gathered scattered information from different sources: approaches to Anglo-Norman literature, Eleanor’s biographies and studies in Arthurian Romance. Nevertheless, mine is not a mere systematization of available data, for both in the light of new discoveries and by contrasting existing information, I have enlarged agreed conclusions and proposed new topics for research and discussion. The year 2004 marked the 800th anniversary of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s death. An exhibition was held at the Abbey of Fontevraud (France), and a long list of books has been published (or re-edited) about the most famous queen of the Middle Ages during these last six years. 1 Starting with R. Lejeune’s seminal work (1954) on 1. -

The Fall of Anne Boleyn (Queen of England Series) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LADY IN THE TOWER : THE FALL OF ANNE BOLEYN (QUEEN OF ENGLAND SERIES) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alison Weir | 544 pages | 03 Jun 2010 | Vintage Publishing | 9780712640176 | English | London, United Kingdom The Lady In The Tower : The Fall of Anne Boleyn (Queen of England Series) PDF Book Yes, there was quite a lot of talk on Twitter re it no being a discovery or new news. Although, not everyone views Anne in the same way that she does! Cheeky plug now! At the Smithsonian Visit. This book isn't about Anne's whole life, just the end However, Henry apparently had made arrangements well in advance and the warrant book showed the scary details kept by Cromwell and the King. Yet he turned away. Henry had Elizabeth brought to Court and paraded at Mass and many entertainments, the grandest of which was a tournament. Catherine of Aragon. All very sad, still, and it is so offensive to our modern senses. Writing Workshops. This was extra fascinating because I was at Hever Castle only last Sunday. For Anne, there was one final indignity. Nobody is her equal but as a peer they can judge her. Two versions of her horrific execution followed but both agree that poor Margaret received many blows of the axe before her suffering was over. They perform functions like preventing the same content from reappearing, ensuring ads are displayed and, in some cases, selecting content based on your interests. Did Cromwell, for reasons of his own, construct a case against Anne and her faction, and then present compelling evidence before the King? I have now seen the Tracy Borman series. -

Ann-Kathrin Deininger and Jasmin Leuchtenberg

STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS WOMEN AND THE GENDER OF SOVEREIGNTY IN EUROPEAN CULTURE EDITED BY ANKE GILLEIR AND AUDE DEFURNE Leuven University Press This book was published with the support of KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). Selection and editorial matter © Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne, 2020 Individual chapters © The respective authors, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. Attribution should include the following information: Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne (eds.), Strategic Imaginations: Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ISBN 978 94 6270 247 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 350 4 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 351 1 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663504 D/2020/1869/55 NUR: 694 Layout: Coco Bookmedia, Amersfoort Cover design: Daniel Benneworth-Gray Cover illustration: Marcel Dzama The queen [La reina], 2011 Polyester resin, fiberglass, plaster, steel, and motor 104 1/2 x 38 inches 265.4 x 96.5 cm © Marcel Dzama. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner TABLE OF CONTENTS ON GENDER, SOVEREIGNTY AND IMAGINATION 7 An Introduction Anke Gilleir PART 1: REPRESENTATIONS OF FEMALE SOVEREIGNTY 27 CAMILLA AND CANDACIS 29 Literary Imaginations of Female Sovereignty in German Romances -

And the Fifth- Bestselling Historian Overall) in the United Kingdom, and Has Sold Over 2.7 Million Books Worldwide

is the top-selling female historian (and the fifth- bestselling historian overall) in the United Kingdom, and has sold over 2.7 million books worldwide. She has published seventeen history books, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII, The Princes in the Tower, Elizabeth the Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry VIII: King and Court, Katherine Swynford, The Lady in the Tower and Elizabeth of York. Alison has also published six historical novels, including Innocent Traitor and The Lady Elizabeth. Her latest biography is The Lost Tudor Princess, about Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox. Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession is the second in her series of novels about the wives of Henry VIII, which began with the Sunday Times bestseller Katherine of Aragon: Untitled-3 1 07/11/2016 14:55 The True Queen. Alison is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences and an Honorary Life Patron of Historic Royal Palaces, and is married with two adult children. By Alison Weir The Six Tudor Queens series Katherine of Aragon: The True Queen Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession Six Tudor Queens Digital Shorts Writing a New Story Arthur: Prince of the Roses The Blackened Heart Fiction Innocent Traitor The Lady Elizabeth The Captive Queen A Dangerous Inheritance The Marriage Game Quick Reads Traitors of the Tower Non-fiction Britain’s Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy The Six Wives of Henry VIII The Princes in the Tower Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII 1547–1558 Elizabeth the Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine -

MEDIEVAL TURNING POINTS INFLUENCED by MY ANCESTORS Such As King Alfred the Great

MEDIEVAL TURNING POINTS INFLUENCED BY MY ANCESTORS Such as King Alfred the Great BY DEAN LADD 2013 INTRODUCTION This is a sequel to my manuscript, Medieval Quest, My Ancestors’ Involvement in Royalty Intrigue. The concept for this writing became readily apparent after listening to the newest Great Courses lectures about these turning points in Medieval history and realizing that my ancestors were key persons in many of the covered events. For instance, Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most remarkable women of the time, having married two kings and being the mother of two kings. Her son, King John, signed the Magna Carta, which wasn’t generally recognized as an important event until much later. Such turning point events shaped and continue to shake the world today. Medieval Quest was written in the journalistic form of “interviews in the period” with five key women, whereas this manuscript is written as normal history to a much greater research depth. It will include the historical impact of many others, extending back to Charles Martel (688-741). King Alfred the Great (849-899) is shown on the cover page. This is his statue, located where he was buried in Winchester, UK. The number of greats, stated in this manuscript, varies slightly from those in Medieval Quest. My following royalty ancestors were key participants in Medieval turning points: Joan Plantagenet, called “The Fair Maid of Kent” (1335-1385 King Edward I of England, called “Long Shanks” (1239-1307) King John of England, called “Lackland” (1166-1216) Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1203) William 1 of England, called “The Conqueror” (1027-1087) Saint Margaret of Scotland (1045-1093) Saint Vladimir of Kiev, Called “The Great” (958-1015) Saint Olga of Kiev (890-969) King Alfred the Great of England (849-899) Rurik the Viking (830-879) Charlemagne of the Franks (742-813) Charles Martel of the Franks, Called “The Hammer” (686-741). -

Partners in Rule: a Study of Twelfth-Century Queens of England

WITTENBERG UNIVERSITY PARTNERS IN RULE: A STUDY OF TWELFTH-CENTURY QUEENS OF ENGLAND AN HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDICACY FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY LAUREN CENGEL SPRINGFIELD, OHIO APRIL 2012 i CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 1. From the Insignificance of Women to Queenship as an Office: A Brief Historiography of Medieval Women and Queenship 5 Chapter 2. Matilda II of Scotland: “Another Esther in Our Times,” r.1100-1118 13 Chapter 3. Matilda III of Boulogne: “A Woman of Subtlety and a Man’s Resolution,” r.1135-1154 43 Chapter 4. Eleanor of Aquitaine: “An Incomparable Woman,” r.1154-1189 65 CONCLUSION 96 APPENDICES 98 BIBLIOGRAPHY 104 1 Introduction By nature, because she was a woman, the woman could not exercise public power. She was incapable of exercising it. – Georges Duby, “Women and Power” With this statement, Georges Duby renders the medieval woman “powerless” to participate in any sort of governance in the Middle Ages. He and other scholars have perpetuated the idea that women who held landed titles in the Middle Ages relegated all power of that title to their husbands, including queens. Scholars have commonly assumed that the king, not the queen, was the only party able to wield significant authority in the governance of the country, and that men dominated the role of the queen in the political sphere. It is difficult to imagine how Duby and others reached his harsh conclusion about women and power in the Middle Ages once the ruling relationships between the kings and queens of twelfth-century England are examined. -

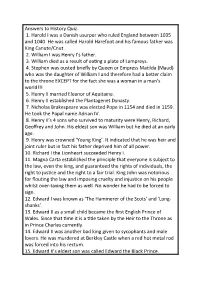

Answers to History Quiz 1

Answers to History Quiz. 1. Harold I was a Danish usurper who ruled England between 1035 and 1040. He was called Harold Harefoot and his famous father was King Canute/Cnut. 2. William I was Henry I’s father. 3. William died as a result of eating a plate of Lampreys. 4. Stephen was ousted briefly by Queen or Empress Matilda (Maud) who was the daughter of William I and therefore had a better claim to the throne EXCEPT for the fact she was a woman in a man’s world!!! 5. Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. 6. Henry II established the Plantagenet Dynasty. 7. Nicholas Brakespeare was elected Pope in 1154 and died in 1159. He took the Papal name Adrian IV. 8. Henry II’s 4 sons who survived to maturity were Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John. His eldest son was William but he died at an early age. 9. Henry was crowned ‘Young King’. It indicated that he was heir and joint ruler but in fact his father deprived him of all power. 10. Richard I the Lionheart succeeded Henry I. 11. Magna Carta established the principle that everyone is subject to the law, even the king, and guaranteed the rights of individuals, the right to justice and the right to a fair trial. King John was notorious for flouting the law and imposing cruelty and injustice on his people whilst over-taxing them as well. No wonder he had to be forced to sign. 12. Edward I was known as ‘The Hammerer of the Scots’ and ‘Long- shanks’. -

The Creation of Anne Boleyn

The Creation of Anne Boleyn In Seach of the Tudors’ Most Notorious Queen SUSAN BORDO ONEWORLD A Oneworld Book First published in Great Britain and the Commonwealth by Oneworld Publications 2014 Originally published in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, New York Copyright © Susan Bordo 2013, 2014 The moral right of Susan Bordo to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-78074-365-3 Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78074-429-2 Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Croydon, UK Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR UK Lines from Anne of the Thousand Days used with permission from the Maxwell Anderson Estate. Copyright 1948 by Maxwell Anderson. Copyright renewal 1975 by Gilda Anderson. Copyright 1950 by Maxwell Anderson. Copyright renewal 1977 by Gilda Anderson. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction: The Erasure of Anne Boleyn and the Creation of “Anne Boleyn” ix Part I: Queen, Interrupted 1. Why You Shouldn’t Believe Everything You’ve Heard About Anne Boleyn 3 2. Why Anne? 20 3. In Love (or Something Like It) 48 4. A Perfect Storm 70 5. The Tower and the Scaffold 97 6. Henry: How Could He Do It? 119 Part II: Recipes for “Anne Boleyn” 7. Basic Historical Ingredients 135 8. Anne’s Afterlives, from She-Tragedy to Historical Romance 146 9. Postwar: Domestic Trouble in the House of Tudor 171 viii • CONTENTS Part III: An Anne for All Seasons 10. -

Well-Behaved Women Rarely Make History: Eleanor of Aquitaine's Political Career and Its Significance to Noblewomen

Issue 5 2016 Funding for Vexillum provided by The Medieval Studies Program at Yale University Issue 5 Available online at http://vexillumjournal.org/ Well-Behaved Women Rarely Make History: Eleanor of Aquitaine’s Political Career and Its Significance to Noblewomen RITA SAUSMIKAT LYCOMING COLLEGE Eleanor of Aquitaine played an indirect role in the formation of medieval and early modern Europe through her resources, wit, and royal connections. The wealth and land the duchess acquired through her inheritance and marriages gave her the authority to financially support religious institutions and the credibility to administrate. Because of her inheritance, Eleanor was a desirable match for Louis VII and Henry II, giving her the title and benefits of queenship. Between both marriages, Eleanor produced ten children, nine of whom became kings and queens or married into royalty and power. The majority of her descendants married royalty or aristocrats across the entire continent, acknowledging Eleanor as the “Grandmother of Europe.” Her female descendants constituted an essential part of court, despite the limitations of women’s authority. Eleanor’s lifelong political career acted as a guiding compass for other queens to follow. She influenced her descendants and successors to follow her famous example in the practices of intercession, property rights, and queenly role. Despite suppression of public authority, women were still able to shape the landscape of Europe, making Eleanor of Aquitaine a trailblazer who transformed politics for future aristocratic women. Eleanor of Aquitaine intrigues scholars and the public alike for her wealthy inheritance, political power, and controversial scandals. Uncertain of the real date, historians estimate Eleanor’s birth year to be either 1122 or 1124. -

1 This Is an Accepted Manuscript of Book

1 “She is my Eleanor”: The Character of Isabella of Angoulême on Film— A Medieval Queen in Modern Media Carey Fleiner Introduction1 The life of Isabella of Angouleme (c. 1188-1246) is the stuff of fiction: At the age of thirteen, the ‘Helen of the Middle Ages,’ was heir to important property in France.2 Supported by her parents, she spurned her fiancé Hugh of Lusignan, Count of La Marche (breaking a legal contract of affiance) in favor of John of England3 (who divorced his first wife for her – and to acquire said property).4 When she was perhaps only between nine and fourteen years old, she was sent to be educated at Hugh’s estate when John fetched her back to Angouleme for a quick wedding. Although the 35-year-old John seems to have waited a few years before consummating the marriage, 5 the chroniclers note that the pair scandalized the court with their vigorous sex life and extravagant living.6 Isabella persuaded first John, then her second husband Hugh, the son of the original fiancé Hugh of Lusignan,7 a powerful castellan (whom she stole from her own preteen daughter, whom she then kidnapped),8 and finally her son Henry III to pursue useless wars against the French—wars which they lost9 when promised Lusignan support failed to show up.10 Isabella declared herself a queen until the day she died,11 refusing to pay homage to her French overlord (the count of Poitou)12—appearing, instead with her family at his home at Christmas in 1242 to beg forgiveness for her and Hugh’s transgressions against his authority;13after a suitably humble display of obeisance, they withdrew and set the place on fire on the way out. -

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Ralph V. Turner Eleanor of Aquitaine Eleanor of Aquitaine, despite medieval notions of women’s innate inferiority, sought power as her two husbands’ partner, and when that proved impossible, defyied them. She paid heavily for her pursuit of power, becoming the object of scurrilous gossip during her lifetime and for centuries afterward. Eleanor, duchess of Aquitaine (1124-1204), is doubtless the most famous or infamous of all medieval queens: she was the wife of Louis VII of France, then wedded to Henry II of England, and she was the mother of three English kings.1 Her life would have been noteworthy in any age, but it was extraordinary by medieval standards. In an age that defined women by their powerlessness, she chose to live as she saw fit, seeking political power despite traditions and teachings of women’s innate inferiority and subordination to males. Eleanor paid heavily for her pursuit of power, becoming the object of scurrilous gossip comparable to that hurled at a later French queen, Marie-Antoinette.2 In a culture of honor and shame, a person’s fama (personal honor or reputation) was all important, determined by the opinion of acquaintances, neighbors, friends or enemies. Common knowledge of one’s shameful character not only brought loss of bona fama, but could result in serious legal and social disabilities.3 Women especially were threatened by rumors of sexual impropriety that could lead to charges against them in the church courts.4 Since ‘the construction of bona fama and mala fama was controlled by men,’ both clerical and secular leaders saw to it that ‘femaleness was defined by the submissiveness of wives to their husbands.’5 Medieval writers ascribed women’s actions to irrational, sentimental or libidinous motives, and Eleanor’s contemporaries attributed her rifts with her two husbands to personal, passionate sources, not to political factors.