MEDIEVAL TURNING POINTS INFLUENCED by MY ANCESTORS Such As King Alfred the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three Minor Revisions

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2001 The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions John Donald Hosler Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Hosler, John Donald, "The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions" (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 21277. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/21277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The reign of King Henry II of England, 1170-74: Three minor revisions by John Donald Hosler A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Major Professor: Kenneth G. Madison Iowa State University Ames~Iowa 2001 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of John Donald Hosler has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 The liberal arts had not disappeared, but the honours which ought to attend them were withheld Gerald ofWales, Topograhpia Cambria! (c.1187) IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION 1 Overview: the Reign of Henry II of England 1 Henry's Conflict with Thomas Becket CHAPTER TWO. -

Elizabeth Thomas Phd Thesis

'WE HAVE NOTHING MORE VALUABLE IN OUR TREASURY': ROYAL MARRIAGE IN ENGLAND, 1154-1272 Elizabeth Thomas A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2001 This item is protected by original copyright Declarations (i) I, Elizabeth Thomas, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in September, 2005, the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2009. Date: Signature of candidate: (ii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date: Signature of supervisor: (iii) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews we understand that we are giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

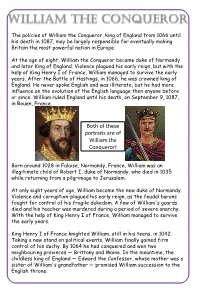

Both of These Portraits Are of William the Conqueror!

The policies of William the Conqueror, king of England from 1066 until his death in 1087, may be largely responsible for eventually making Britain the most powerful nation in Europe. At the age of eight, William the Conqueror became duke of Normandy and later King of England. Violence plagued his early reign, but with the help of King Henry I of France, William managed to survive the early years. After the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, he was crowned king of England. He never spoke English and was illiterate, but he had more influence on the evolution of the English language then anyone before or since. William ruled England until his death, on September 9, 1087, in Rouen, France. Both of these portraits are of William the Conqueror! Born around 1028 in Falaise, Normandy, France, William was an illegitimate child of Robert I, duke of Normandy, who died in 1035 while returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. At only eight years of age, William became the new duke of Normandy. Violence and corruption-plagued his early reign, as the feudal barons fought for control of his fragile dukedom. A few of William's guards died and his teacher was murdered during a period of severe anarchy. With the help of King Henry I of France, William managed to survive the early years. King Henry I of France knighted William, still in his teens, in 1042. Taking a new stand on political events, William finally gained firm control of his duchy. By 1064 he had conquered and won two neighbouring provinces — Brittany and Maine. -

Download Download

Of Palaces, Hunts, and Pork Roast: Deciphering the Last Chapters of the Capitulary of Quierzy (a. 877) Martin Gravel Politics depends on personal contacts.1 This is true in today’s world, and it was certainly true in early medieval states. Even in the Carolingian empire, the larg- est Western polity of the period, power depended on relations built on personal contacts.2 In an effort to nurture such necessary relationships, the sovereign moved with his court, within a network of important political “communication centres”;3 in the ninth century, the foremost among these were his palaces, along with certain cities and religious sanctuaries. And thus, in contemporaneous sources, the Latin term palatium often designates not merely a royal residence but the king’s entourage, through a metonymic displacement that shows the importance of palatial grounds in * I would like to thank my fellow panelists at the International Medieval Congress (Leeds, 2011): Stuart Airlie, Alexandra Beauchamp, and Aurélien Le Coq, as well as our session organizer Jens Schneider. This paper has greatly benefited from the good counsel of Jennifer R. Davis, Eduard Frunzeanu, Alban Gautier, Maxime L’Héritier, and Jonathan Wild. I am also indebted to Eric J. Goldberg, who was kind enough to read my draft and share insightful remarks. In the final stage, the precise reading by Florilegium’s anonymous referees has greatly improved this paper. 1 In this paper, the term politics will be used in accordance with Baker’s definition, as rephrased by Stofferahn: “politics, broadly construed, is the activity through which individuals and groups in any society articulate, negotiate, implement, and enforce the competing claims they make upon one another”; Stofferahn, “Resonance and Discord,” 9. -

My Ancestors Who Lived in Leeds Castle (And Some of Them Even Owned It!)

Chapter 75 My Ancestors Who Lived in Leeds Castle (and Some of Them Even Owned It!) [originally written 4 January 2021] On 20 December 2020, Russ Leisenheimer posted a photo of a sunset over Leeds Castle to his Facebook page.1 Russ was one of my high school classmates in Euclid, Ohio, and he still lives in the Cleveland area. Here is the photo: I have been using the “World Family Tree” on Geni.com to investigate my European ancestors who lived during the Middle Ages, and seeing the photo of Leeds Castle got me to wondering if any of my ancestors lived there. OK, I realized that this was going to be a long shot, but due to the coronavirus pandemic, I have lots of free time to look into such seemingly trifling things. I immediately went to Wikipedia.org to learn about Leeds Castle, and that prompted the following reply to Russ on Facebook: Wikipedia states that “Leeds Castle is a castle in Kent, England, 5 miles (8 km) southeast of Maidstone. A castle has existed on the site since 1119, the first being a simple stone stronghold constructed by Robert de Crevecoeur which served as a military post in the time of Norman intrusions into England. In the 13th century, it came into the hands of King Edward I, for whom it became a favourite residence; in the 16th century, Henry VIII used it as a dwelling for his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.” According to the World Family Tree on Geni.com, Robert de Crevecoeur was my 25th great uncle. -

Philippa of Hainaut, Queen of England

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY VMS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/philippaofhainauOOwhit PHILIPPA OF HAINAUT, QUEEN OF ENGLAND BY LEILA OLIVE WHITE A. B. Rockford College, 1914. THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL ..%C+-7 ^ 19</ 1 HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ftlil^ &&L^-^ J^B^L^T 0^ S^t ]J-CuJl^^-0<-^A- tjL_^jui^~ 6~^~~ ENTITLED ^Pt^^L^fifi f BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF CL^t* *~ In Charge of Major Work H ead of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination CONTENTS Chapter I Philippa of Hainaut ---------------------- 1 Family and Birth Queen Isabella and Prince Edward at Valenciennes Marriage Arrangement -- Philippa in England The Wedding at York Coronation Philippa's Influence over Edward III -- Relations with the Papacy - - Her Popularity Hainauters in England. Chapter II Philippa and her Share in the Hundred Years' War ------- 15 English Alliances with Philippa's Relatives -- Emperor Louis -- Count of Hainaut Count of Juliers Vow of the Heron Philippa Goes to the Continent -- Stay at Antwerp -- Court at Louvain -- Philippa at Ghent Return to England Contest over the Hainaut Inherit- ance -- Battle of Neville's Cross -- Philippa at the Siege of Calais. Chapter III Philippa and her Court -------------------- 29 Brilliance of the English Court -- French Hostages King John of France Sir Engerraui de Coucy -- Dis- tinguished Visitors -- Foundation of the Round Table -- Amusements of the Court -- Tournaments -- Hunting The Black Death -- Extravagance of the Court -- Finan- cial Difficulties The Queen's Revenues -- Purveyance-- uiuc s Royal Manors « Philippa's Interest in the Clergy and in Religious Foundations — Hospital of St. -

The Flower of English Chivalry

David Green. Edward the Black Prince: Power in Medieval Europe. Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2007. 312 pp. $28.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-582-78481-9. Reviewed by Stephen M. Cooper Published on H-War (January, 2008) In the city square of Leeds in West Yorkshire, the 1360s. He never became king of England, but there is a magnificent statue of the Black Prince, he was the sovereign ruler of a large part of erected in 1903 when the British Empire was at its France. The prince was a brilliant soldier and height and patriotism was uncomplicated. Dis‐ commander, but he was "not a political animal," playing an intense pride in his life and achieve‐ and there is a strong argument for saying that he ments, the inscription proclaims that the prince won the war but lost the peace because of his mis‐ was "the victor of Crécy and Poitiers, the Flower government of Aquitaine (p. 153). In pursuing his of English Chivalry and the Upholder of the Rights chosen themes, Green deliberately plays down the of the People in the Good Parliament." One would fighting, at which the prince was very good, and not expect a book published in 2007 to make the concentrates on the politics, where the prince was same grandiose claims, and David Green does not either rather hopeless or simply uninterested. In even intend his newest book Edward the Black terms of religion and estate management, there is Prince to be a conventional biography--he has no real evidence that "the Flower of English written one of those already (The Black Prince Chivalry" was even personally involved. -

•Œso Hard Was It to Release Princes Whom Fortuna Had Put In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online “So Hard was it to Release Princes whom Fortuna had put in her Chains:”1 Queens and Female Rulers as Hostage- and Captive-Takers and Holders Colleen Slater ostage- and captive-taking2 were fundamental processes in medieval warfare and medieval society in general. Despite this H importance, however, only recently have these practices received significant scholarly attention, and certain aspects of these customs have been overlooked; in particular, the relationship of women to these prac- tices, which has been explored by only one scholar, Yvonne Friedman.3 Friedman’s work on female captives, while illuminating, only focuses on women as passive victims of war; that is, as captives to be taken, sold, or traded. In fact, the idea that women could only be victims of hostage- and captive-taking is almost universally assumed in the scholarship. But some women from the highest echelons of medieval society figure in the story as a good deal more than passive victims. The sources are littered with examples that not only illuminate the importance of women and gender to the customs/practices associated with hostages and captives, but also how women used them to exercise power and independence militarily, politically, and socially. Able to take matters into their own hands, these women played the game of politics, ruled their own or their husbands’ lands, and participated in the active taking and holding of hostages and captives. Examining these women is essential not only for expanding our knowledge of the more general processes of hostage- and captive-taking and holding, but also for understanding how and why women were able (or unable) to navigate them. -

Shakespeare's

Shakespeare’s Henry IV: s m a r t The Shadow of Succession SHARING MASTERWORKS OF ART April 2007 These study materials are produced for use with the AN EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH OF BOB JONES UNIVERSITY Classic Players production of Henry IV: The Shadow of Succession. The historical period The Shadow of Succession takes into account is 1402 to 1413. The plot focuses on the Prince of Wales’ preparation An Introduction to to assume the solemn responsibilities of kingship even while Henry IV regards his unruly son’s prospects for succession as disastrous. The Shadow of When the action of the play begins, the prince, also known as Hal, finds himself straddling two worlds: the cold, aristocratic world of his Succession father’s court, which he prefers to avoid, and the disreputable world of Falstaff, which offers him amusement and camaraderie. Like the plays from which it was adapted, The Shadow of Succession offers audiences a rich theatrical experience based on Shakespeare’s While Henry IV regards Falstaff with his circle of common laborers broad vision of characters, events and language. The play incorporates a and petty criminals as worthless, Hal observes as much human failure masterful blend of history and comedy, of heroism and horseplay, of the in the palace, where politics reign supreme, as in the Boar’s Head serious and the farcical. Tavern. Introduction, from page 1 Like Hotspur, Falstaff lacks the self-control necessary to be a produc- tive member of society. After surviving at Shrewsbury, he continues to Grieved over his son’s absence from court at a time of political turmoil, squander his time in childish pleasures. -

King Henry II & Thomas Becket

Thomas a Becket and King Henry II of England A famous example of conflict between a king and the Medieval Christian Church occurred between King Henry II of England and Thomas a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. King Henry and Becket were onetime friends. Becket had been working as a clerk for the previous Archbishop of Canterbury. This was an important position because the Archbishop of Canterbury was the head of the Christian Church in England. Thomas Becket was such an efficient and dedicated worker he was eventually named Lord Chancellor. The Lord Chancellor was a clerk who worked directly for the king. In 1162, Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died. King Henry saw this as an opportunity to increase his control over the Christian Church in England. He decided to appoint Thomas Becket to be the new Archbishop of Canterbury reasoning that, because of their relationship, Becket would support Henry’s policies. He was wrong. Instead, Becket worked vigorously to protect the interests of the Church even when that meant disagreeing with King Henry. Henry and Becket argued over tax policy and control of church land but the biggest conflict was over legal rights of the clergy. Becket claimed that if a church official was accused of a crime, only the church itself had the ability to put the person on trial. King Henry said that his courts had jurisdiction over anyone accused of a crime in England. This conflict became increasingly heated until Henry forced many of the English Bishops and Archbishops to agree to the Constitution of Clarendon. -

Eleanor and the Angevin Empire

Eleanor and the Angevin Empire History Lesson 2 of an enquiry of 4 lessons Enquiry: What can the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine tell us about who held power in the Middle Ages? Ms Barnett Mr Arscott 1152 Eleanor’s marriage to King Louis VII of France ended in 1152. Once the couple had separated Eleanor returned to Aquitaine to rule as Duchess. Aged 28, Eleanor once again became a desired bride in Europe. She was single, young enough to have more children and in charge of a powerful and rich area of southern France. Eleanor was so desirable as a bride that two men tried to kidnap her on her journey from Paris to Aquitaine. Eleanor managed to avoid capture. Instead she focused on entering into marriage in a more traditional way. 8 weeks and 2 days after her separation from Louis, Eleanor married once again. Eleanor and Henry Eleanor’s second husband was 19 year old Henry. He was Duke of Normandy as well as the Count of Anjou and Maine. This marriage was controversial at the time. Firstly Henry was 9 years younger than Eleanor. Traditionally in the Middle Ages older men married younger women, not the other way round! Also, Eleanor’s second marriage happened only 8 weeks after her separation from King Louis. A chronicle from the time said that Eleanor and Henry married “without the pomp and ceremony that befitted their rank.” It wasn’t a big ceremony and didn’t reflect their wealth and importance. Why was this wedding arranged so quickly? Increased territories It is possible the wedding took place quickly because Henry was seen as a controversial choice. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of