True Clothes Moths (Tinea Pellionella, Et Al.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bon Echo Provincial Park

BON ECHO PROVINCIAL PARK One Malaise trap was deployed at Bon Echo Provincial Park in 2014 (44.89405, -77.19691 278m ASL; Figure 1). This trap collected arthropods for twenty weeks from May 7 – September 24, 2014. All 10 Malaise trap samples were processed; every other sample was analyzed using the individual specimen protocol while the second half was analyzed via bulk analysis. A total of 2559 BINs were obtained. Over half the BINs captured were flies (Diptera), followed by bees, ants and wasps (Hymenoptera), moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera), and beetles (Coleoptera; Figure 2). In total, 547 arthropod species were named, representing 22.9% of the BINs from the site (Appendix 1). All BINs were assigned at least to Figure 1. Malaise trap deployed at Bon Echo family, and 57.2% were assigned to a genus (Appendix Provincial Park in 2014. 2). Specimens collected from Bon Echo represent 223 different families and 651 genera. Diptera Hymenoptera Lepidoptera Coleoptera Hemiptera Mesostigmata Trombidiformes Psocodea Sarcoptiformes Trichoptera Araneae Entomobryomorpha Symphypleona Thysanoptera Neuroptera Opiliones Mecoptera Orthoptera Plecoptera Julida Odonata Stylommatophora Figure 2. Taxonomy breakdown of BINs captured in the Malaise trap at Bon Echo. APPENDIX 1. TAXONOMY REPORT Class Order Family Genus Species Arachnida Araneae Clubionidae Clubiona Clubiona obesa Linyphiidae Ceraticelus Ceraticelus atriceps Neriene Neriene radiata Philodromidae Philodromus Salticidae Pelegrina Pelegrina proterva Tetragnathidae Tetragnatha Tetragnatha shoshone -

Nuisance Insects and Climate Change

www.defra.gov.uk Nuisance Insects and Climate Change March 2009 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Nobel House 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Tel: 020 7238 6000 Website: www.defra.gov.uk © Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2007 This publication is value added. If you wish to re-use this material, please apply for a Click-Use Licence for value added material at http://www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/value-added-licence- information/index.htm. Alternatively applications can be sent to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ; Fax: +44 (0)1603 723000; email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Local Environment Protection Defra Nobel House Area 2A 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Email: [email protected] This document is also available on the Defra website and has been prepared by Centre of Ecology and Hydrology. Published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 2 An Investigation into the Potential for New and Existing Species of Insect with the Potential to Cause Statutory Nuisance to Occur in the UK as a Result of Current and Predicted Climate Change Roy, H.E.1, Beckmann, B.C.1, Comont, R.F.1, Hails, R.S.1, Harrington, R.2, Medlock, J.3, Purse, B.1, Shortall, C.R.2 1Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, 2Rothamsted Research, 3Health Protection Agency March 2009 3 Contents Summary 5 1.0 Background 6 1.1 Consortium to perform the work 7 1.2 Objectives 7 2.0 -

Clothes Moths ENTFACT-609 by Michael F

Clothes Moths ENTFACT-609 By Michael F. Potter, Extension Entomologist, University of Kentucky Clothes moths are pests that can destroy fabric and other materials. They feed exclusively on animal fibers, especially wool, fur, silk, feathers, felt, and leather. These materials contain keratin, a fibrous protein that the worm-like larvae of the clothes moth can digest. (In nature, the larvae feed on the nesting materials or carcasses of birds and mam- mals.) Cotton and synthetic fabrics such as poly- ester and rayon are rarely attacked unless blended with wool, or heavily soiled with food stains or body oils. Serious infestations of clothes moths Fig. 1b: Indianmeal moth can develop undetected in dwellings, causing ir- Two different types of clothes moths are common reparable harm to vulnerable materials. in North America — the webbing clothes moth Facts about Clothes Moths (Tineola bisselliella) and the casemaking clothes moth (Tinea pellionella). Adult webbing clothes Clothes moths are small, 1/2-inch moths that are moths are a uniform, buff-color, with a small tuft beige or buff-colored. They have narrow wings of reddish hairs on top of the head. Casemaking that are fringed with small hairs. They are often clothes moths are similar in appearance, but have mistaken for grain moths infesting stored food dark specks on the wings. Clothes moth adults do items in kitchens and pantries. Unlike some other not feed so they cause no injury to fabrics. How- types of moths, clothes moths are seldom seen be- ever, the adults lay about 40-50 pinhead-sized cause they avoid light. -

Contribution to the Lepidoptera Fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X 51 (2001) 1 S. 161 - 213 14.09.2001 Contribution to the Lepidoptera fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2. Tineidae, Acrolepiidae, Epermeniidae With 127 figures Reinhard Gaedike and Ole Karsholt Summary A review of three families Tineidae, Epermeniidae and Acrolepiidae in the Madeira Islands is given. Three new species: Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. and A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) are described, and two new combinations in the Tineidae: Ceratobia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. n. and Monopis barbarosi (KOÇAK) comb. n. are listed. Trichophaga robinsoni nom. n. is proposed as a replacement name for the preoccupied T. abrkptella (WOLLASTON, 1858). The first record from Madeira of the family Acrolepiidae (with Acrolepiopsis vesperella (ZELLER) and the two above mentioned new species) is presented, and three species of Tineidae: Stenoptinea yaneimarmorella (MILLIÈRE), Ceratobia oxymora (MEY RICK) and Trichophaga tapetgella (LINNAEUS) are reported as new to the fauna of Madeira. The Madeiran records given for Tsychoidesfilicivora (MEYRICK) are the first records of this species outside the British Isles. Tineapellionella LINNAEUS, Monopis laevigella (DENIS & SCHIFFERMULLER) and M. imella (HÜBNER) are dele ted from the list of Lepidoptera found in Madeira. All species and their genitalia are figured, and informa tion on bionomy is presented. Zusammenfassung Es wird eine Übersicht über die drei Familien Tineidae, Epermeniidae und Acrolepiidae auf den Madeira Inseln gegeben. Die drei neuen Arten Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. und A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) werden beschrieben, zwei neue Kombinationen bei den Tineidae: Cerato bia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. -

Lepidoptera: Tineidae

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X 56 (2006) 1 S. 213-229 15.08.2006 Some new or poorly known tineids from Central Asia, the Russian Far East and China (Lepidoptera: T in e id a e ) With 18 figures R e in h a r d G a e d ik e Summary Results are presented of the examination of tineid material from the Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH) and the Institute of Animal Systematics and Ecology, Siberian Zoological Museum Novosibirsk (SZMN). As new species are described Tinea albomaculata from China, Tinea fiiscocostalis from Russia, Tinea kasachica from Kazachstan, and Monopis luteocostalis from Russia. The previously unknown male of Tinea semifulvelloides is described. New records for several countries for 15 species are established. Zusammenfassung Es werden die Ergebnisse der Untersuchung von Tineidenmaterial aus dem Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH), und aus dem Institute of Animal Systematics and Ecology, Siberian Zoological Museum Novosibirsk (SZMN) vorgelegt. Als neu werden beschrieben Tinea albom aculata aus China, Tinea fuscocostalis aus Russland, Tinea kasachica aus Kasachstan und Monopis luteocostalis aus Russland. Von Tinea semifitlvelloides war es möglich, das bisher unbekannte Männchen zu beschreiben. Neufunde für verschiede ne Länder wurden für 15 Arten festgestellt. Keywords Tineidae, faunistics, taxonomy, four new species, new records, Palaearctic region. My collègue L a u r i K a il a from the Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH) was so kind as to send me undetermined Tineidae, collected by several Finnish entomologists during recent years in various parts of Russia (Siberia, Buryatia, Far East), in Central Asia, and China. -

Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk

Dumfries & Galloway Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk. Keith is a former Dumfries & Galloway Council ranger and now helps to run Nocturnal Wildlife Tours based in Castle Douglas. The tours use a specially prepared night tours vehicle, complete with external mounted thermal camera and internal viewing screens. Each participant also has their own state- of-the-art thermal imaging device to use for the duration of the tour. This allows participants to detect animals as small as rabbits at up to 300 metres away or get close enough to see Badgers and Roe Deer going about their nightly routine without them knowing you’re there. For further information visit www.wildlifetours.co.uk email [email protected] or telephone 07483 131791 Contributing photographers p2 Small White butterfly © Ian Findlay, p4 Colvend coast ©Mark Pollitt, p5 Bittersweet © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Wildflower grassland ©Mark Pollitt, p6 Oblong Woodsia planting © National Trust for Scotland, Oblong Woodsia © Chris Miles, p8 Birdwatching © castigatio/Shutterstock, p9 Hedgehog in grass © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Hedgehog in leaves © Mark Bridger/Shutterstock, Hedgehog dropping © northeastwildlife.co.uk, p10 Cetacean watch at Mull of Galloway © DGERC, p11 Common Carder Bee © Bob Fitzsimmons, p12 Black Grouse confrontation © Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, p13 Black Grouse male ©Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, Female Black Grouse in flight © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Common Pipistrelle bat © Steven Farhall/ Shutterstock, p14 White Ermine © Mark Pollitt, -

Webbing Clothes Moth

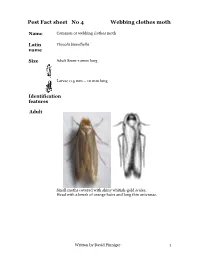

Pest Fact sheet No 4 Webbing clothes moth Name Common or webbing clothes moth Latin Tineola bisselliella name Size Adult 8mm-10mm long Larvae 0.5 mm – 10 mm long Identification features Adult Small moths covered with shiny whitish-gold scales. Head with a brush of orange hairs and long thin antennae. Written by David Pinniger 1 Larva White with an orange-brown head capsule. Often hidden by tubes of silk webbing. Written by David Pinniger 2 Life cycle Adult moths fly well when it is warm and females lay batches of eggs on wool, fur, feathers and other organic materials. When the larvae first hatch they are extremely small, less than 0.5 mm, and they remain in the material where they have hatched. As they feed and grow, they secrete silk webbing which sticks to the material they are living on. As they get larger, the silk forms tubes around them. They prefer dark undisturbed places and are rarely seen unless disturbed. In unheated buildings, the larvae may take nearly a year to complete their growth and each new cycle starts after they pupate and change into adults in the Spring. In heated buildings they may complete two complete cycles per year with another emergence of adult moths in the Autumn. In very warm buildings there may even be three generations per year with moths appearing at any time. Signs of damage Irregular holes, silk webbing and gritty pellets of excreta, called frass, are signs of moth attack. Silk webbing on wool carpet Written by David Pinniger 3 Silk webbing stuck to canvas fabric Materials The larvae are voracious feeders and will graze on and make damaged holes in woollen textiles, animal specimens, fur and feathers. -

Genetically Modified Baculoviruses for Pest

INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS This page intentionally left blank INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS EDITED BY LAWRENCE I. GILBERT SARJEET S. GILL Amsterdam • Boston • Heidelberg • London • New York • Oxford Paris • San Diego • San Francisco • Singapore • Sydney • Tokyo Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press, 32 Jamestown Road, London, NW1 7BU, UK 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA ª 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved The chapters first appeared in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, edited by Lawrence I. Gilbert, Kostas Iatrou, and Sarjeet S. Gill (Elsevier, B.V. 2005). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (þ44) 1865 843830, fax (þ44) 1865 853333, e-mail [email protected]. Requests may also be completed on-line via the homepage (http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissions). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Insect control : biological and synthetic agents / editors-in-chief: Lawrence I. Gilbert, Sarjeet S. Gill. – 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 (alk. paper) 1. Insect pests–Control. 2. Insecticides. I. Gilbert, Lawrence I. (Lawrence Irwin), 1929- II. Gill, Sarjeet S. SB931.I42 2010 632’.7–dc22 2010010547 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 Cover Images: (Top Left) Important pest insect targeted by neonicotinoid insecticides: Sweet-potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci; (Top Right) Control (bottom) and tebufenozide intoxicated by ingestion (top) larvae of the white tussock moth, from Chapter 4; (Bottom) Mode of action of Cry1A toxins, from Addendum A7. -

Species List

Species List for <vice county> [Staffordshire (VC 39)] Code Taxon Vernacular 1.001 Micropterix tunbergella 1.002 Micropterix mansuetella 1.003 Micropterix aureatella 1.004 Micropterix aruncella 1.005 Micropterix calthella 2.001 Dyseriocrania subpurpurella 2.003 Eriocrania unimaculella 2.004 Eriocrania sparrmannella 2.005 Eriocrania salopiella 2.006 Eriocrania cicatricella 2.006 Eriocrania haworthi 2.007 Eriocrania semipurpurella 2.008 Eriocrania sangii 3.001 Triodia sylvina Orange Swift 3.002 Korscheltellus lupulina Common Swift 3.003 Korscheltellus fusconebulosa Map-winged Swift 3.004 Phymatopus hecta Gold Swift 3.005 Hepialus humuli Ghost Moth 4.002 Stigmella lapponica 4.003 Stigmella confusella 4.004 Stigmella tiliae 4.005 Stigmella betulicola 4.006 Stigmella sakhalinella 4.007 Stigmella luteella 4.008 Stigmella glutinosae 4.009 Stigmella alnetella 4.010 Stigmella microtheriella 4.012 Stigmella aceris 4.013 Stigmella malella Apple Pygmy 4.015 Stigmella anomalella Rose Leaf Miner 4.017 Stigmella centifoliella 4.018 Stigmella ulmivora 4.019 Stigmella viscerella 4.020 Stigmella paradoxa 4.022 Stigmella regiella 4.023 Stigmella crataegella 4.024 Stigmella magdalenae 4.025 Stigmella nylandriella 4.026 Stigmella oxyacanthella 4.030 Stigmella hybnerella 4.032 Stigmella floslactella 4.034 Stigmella tityrella 4.035 Stigmella salicis 4.036 Stigmella myrtillella 4.038 Stigmella obliquella 4.039 Stigmella trimaculella 4.040 Stigmella assimilella 4.041 Stigmella sorbi 4.042 Stigmella plagicolella 4.043 Stigmella lemniscella 4.044 Stigmella continuella -

Natural History of Lepidoptera Associated with Bird Nests in Mid-Wales

Entomologist’s Rec. J. Var. 130 (2018) 249 NATURAL HISTORY OF LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH BIRD NESTS IN MID-WALES D. H. B OYES Bridge Cottage, Middletown, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 8DG. (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract Bird nests can support diverse communities of invertebrates, including moths (Lepidoptera). However, the understanding of the natural history of these species is incomplete. For this study, 224 nests, from 16 bird species, were collected and the adult moths that emerged were recorded. The majority of nests contained moths, with 4,657 individuals of ten species recorded. Observations are made on the natural history of each species and some novel findings are reported. The absence of certain species is discussed. To gain deeper insights into the life histories of these species, it would be useful to document the feeding habits of the larvae in isolation. Keywords : Commensal, detritivore, fleas, moths, Tineidae. Introduction Bird nests represent concentrated pockets of organic resources (including dead plant matter, feathers, faeces and other detritus) and can support a diverse invertebrate fauna. A global checklist compiled by Hicks (1959; 1962; 1971) lists eighteen insect orders associated with bird nests, and a study in England identified over 120 insect species, spanning eight orders (Woodroffe, 1953). Moths are particularly frequent occupants of bird nests, but large gaps in knowledge and some misapprehensions remain. For example, Tineola bisselliella (Hummel, 1823) was widely thought to infest human habitations via bird nests, which acted as natural population reservoirs. However, it has recently been discovered that this non-native species seldom occurs in rural bird nests and can be regarded as wholly synanthropic in Europe, where it was introduced from Africa around the turn of the 19th century (Plarre & Krüger- Carstensen, 2011; Plarre, 2014). -

The Rise of Network Ecology: Maps of the Topic Diversity and Scientific Collaboration

The Rise of Network Ecology: Maps of the topic diversity and scientific collaboration Stuart R. Borrett *,a,c, James Moody b,c, Achim Edelmann b,c a Department of Biology b Department of Sociology c Duke Network Analysis and Marine Biology Duke University Center University of North Durham, NC 27708 Social Science Research Carolina Wilmington Institute Wilmington, NC 28403 Duke University Durham, NC 27708 * Corresponding Author, [email protected], 910-962-2411 Abstract Network ecologists investigate the structure, function, and evolution of ecological systems using network models and analyses. For example, network techniques have been used to study community interactions (i.e., food-webs, mutualisms), gene flow across landscapes, and the sociality of individuals in populations. The work presented here uses a bibliographic and network approach to (1) document the rise of Network Ecology, (2) identify the diversity of topics addressed in the field, and (3) map the structure of scientific collaboration among contributing scientists. Our aim is to provide a broad overview of this emergent field that highlights its diversity and to provide a foundation for future advances. To do this, we searched the ISI Web of Science database for ecology publications between 1900 and 2012 using the search terms for research areas of Environmental Sciences & Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the topic tag ecology. From these records we identified the Network Ecology publications using the topic terms network, graph theory, and web while controlling for the usage of misleading phrases. The resulting corpus entailed 29,513 publications between 1936 and 2012. We find that Network Ecology spans across more than 1,500 sources with core ecological journals being among the top 20 most frequent outlets. -

Biological Infestations Page

Chapter 5: Biological Infestations Page A. Overview ........................................................................................................................... 5:1 What information will I find in this chapter? ....................................................................... 5:1 What is a museum pest? ................................................................................................... 5:1 What conditions support museum pest infestations? ....................................................... 5:2 B. Responding to Infestations ............................................................................................ 5:2 What should I do if I find live pests or signs of pests in or around museum collections? .. 5:2 What should I do after isolating the infested object? ......................................................... 5:3 What should I do after all infested objects have been removed from the collections area? ................................................................................................ 5:5 What treatments can I use to stop an infestation? ............................................................ 5:5 C. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) ................................................................................ 5:8 What is IPM? ..................................................................................................................... 5:9 Why should I use IPM? .....................................................................................................