Supporting Small Forest Enterprises Reports from the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class Struggle, Popular Culture and the Politics of Akpeteshie (Local Gin) in Ghana, 1930-67*

Journal of African History, 37 (1996), pp. 215-236 215 Copyright © 1996 Cambridge University Press WHAT'S IN A DRINK? CLASS STRUGGLE, POPULAR CULTURE AND THE POLITICS OF AKPETESHIE (LOCAL GIN) IN GHANA, 1930-67* BY EMMANUEL AKYEAMPONG Harvard University Wunni ntramma na wo se nsa nye de When you do not have cowry shells, you say wine is not sweet (Twi Proverb). SOCIAL revolutions or movements of popular protest often begin innoc- uously. They are initially preoccupied with 'bread-and-butter' politics and with no sophisticated ideology of class-consciousness or a desire to overturn the social order. Adherents to such movements — the weak and poor — seek to minimize the disadvantages of the 'system' for their lives.1 In the Gold Coast from the 1930s, an excellent arena for popular protest centered on African demands to distill akpeteshie (local gin). Distilled from fermented palm wine or sugar cane juice, and requiring a simple apparatus of two tins (usually four-gallon kerosene tins) and copper tubing,2 akpeteshie quickly became a lucrative industry in an era of economic depression, incorporating extensive production and retail networks. But, far from being associated with just the right to distill spirits, akpeteshie became embroiled in African politics under colonial rule as world depression, World War II and the intensification of nationalism prompted an African re-evaluation of the colonial situation. Local distillation of akpeteshie became widespread in the Gold Coast after 1930, when temperance interests secured restrictive liquor legislation raising the tariffs on imported liquor. As previous increases in import duties on liquor had not adversely affected import levels and the liquor revenues so * Research for this article was made possible by research grants from the African Development Foundation in 1991-2 and from the William F. -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

A Socio- Economic History of Alcohol in Southeastern Nigeria Since 1890

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study Alcohol has various socio-economic and cultural functions among the people of southeastern Nigeria. It is used in rituals, marriages, oath taking, festivals and entertainment. It is presented as a mark of respect and dignity. The basic alcoholic beverage produced and consumed in the area was palm -wine tapped from the oil palm tree or from the raffia- palm. Korieh notes that, from the fifteenth century contacts between the Europeans and peoples of eastern Nigeria especially during the Atlantic slave trade era, brought new varieties of alcoholic beverages primarily, gin and whisky.1 Thus, beginning from this period, gins especially schnapps from Holland became integrated in local culture of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria and even assumed ritual position.2 From the 1880s, alcohol became accepted as a medium of exchange for goods and services and a store of wealth.3 By the early twentieth century, alcohol played a major role in the Nigerian economy as one third of Nigeria‘s income was derived from import duties on liquor.4 Nevertheless, prior to the contact of the people of Southern Nigeria with the Europeans, alcohol was derived mainly from the oil palm and raffia palm trees which were numerous in the area. These palms were tapped and the sap collected and drunk at various occasions. From the era of the Trans- Atlantic slave trade, the import of gin, rum and whisky became prevalent.These were used in ex-change for slaves and to pay comey – a type of gratification to the chiefs. Even with the rise of legitimate trade in the 19th century alcoholic beverages of various sorts continued to play important roles in international trade.5 Centuries of importation of gin into the area led to the entrenchment of imported gin in the culture of the people. -

Consumption System of Rattan in Ghana

A study of the Production-to- Consumption System of Rattan in Ghana by A. Oteng-Amoako (Dr.) Project Leader B. Darko Obiri (Mrs): Socio-Economist S. Britwum (Ms): Computer Analyst J. K Afful-Mensah (Mr.): Research Assistant J. Asiedu (Mr.): Research Assistant E. Ebanyenle (Mr.): Project Assistant FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF GHANA and INTERNATIONAL NETWORK FOR BAMBOO AND RATTAN Executive Summary Rattans are climbing palms native to tropical forest regions of South-east Asia, the Malay Archipelago and Africa. There are over 650 rattan species worldwide (UhI and Dransfield 1987). Rattans have a wide variety of both household and commercial uses. Recently, their importance in environmental management and conservation has also been recognized. Rattans provide raw materials for the cane furniture industry. About 0.7 billion of the world’s population are involved in the trade of raw rattan materials and their finished products (Dransfield and Manokaran, 1994)., Rattan provides a means of livelihood for collectors, processors and traders in the rattan producing countries of Africa. In Ghana, rattan contributes 20% of the total revenue from NTFPs. Through the National Forest Policy the government of Ghana is promoting the development of NTFPs including rattan to curb rural poverty and ensure sustainable forest resources. Despite its environmental and socio-economic importance to the nation, the rattan sector lacks adequate authoritative basic data required to enhance its development. The study was principally designed to provide a thorough understanding of the rattan production-to-consumption system in Ghana. It was also to identify constraints in the sector and recommend possible development interventions that will transcend these constraints and ensure sustainable development of the sector to particularly, improve the livelihood of the rural stakeholders in the country. -

ISCO) Major Groups, Sub-Major Groups, Minor Groups and Unit Groups

S T R U C T U R E D C O D E L I S T I N T E R N A T I O N A L S T A N D A R D C L A S S I F I C A T I O N O F O C C U P A T I O N S [I S C O] ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ GHANA STATISTICAL SERVICE AUGUST 2010 GROUP TITLES AND CODES Code Major Group Page 0 Armed forces occupations 1 1 Managers 2 2 Professionals 9 3 Technicians and associate professionals 27 4 Clerical support workers 44 5 Service and sales workers 48 6 Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers 55 7 Craft and related trades workers 58 8 Plant and machine operators, and assemblers 72 9 Elementary occupations 80 International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) Major groups, sub-major groups, minor groups and unit groups 0 Armed forces occupations 01 Commissioned armed forces officers 011 Commissioned armed forces officers 0110 Commissioned armed forces officers 0110 Admiral 0110 Air commodore 0110 Air marshal 0110 Brigadier (army) 0110 Captain (air force) 0110 Captain (navy) 0110 Colonel (army) 0110 Field marshal 0110 Flying officer (military) 0110 General (army) 0110 Group captain (air force) 0110 Lieutenant (army) 0110 Lieutenant, flight 0110 Major (army) 0110 Midshipman 0110 Naval officer (military) 0110 Navy commander 0110 Officer cadet (armed forces) 0110 Second lieutenant (army) 0110 Squadron leader 0110 Sub-lieutenant (navy) 0110 Wing commander 02 Non-commissioned armed forces officers 021 Non-commissioned armed forces officers 0210 Non-commissioned armed forces officers 0210 Boatswain (navy) 0210 Flight sergeant 0210 -

Tagbo Falls Lodge Menu

HOT DRINKS TAGBO FALLS LODGE Ghana Filter Coffee per cup 6 Ghc Per pot 16 Ghc MENU Black or Herbal Tea Per cup 3 Ghc Per pot 5 Ghc Discover our special menu, with flavors of the region and beyond. We offer Tagbo Traditional dishes as well as Tagbo Hot Chocolate Per cup 5 Ghc World dishes. SOFT DRINKS All meals are prepared with care and love by Philo and the team, using (mostly) locally produced products. Lemonade or Bissap Per 500 ml 10 Ghc Per 1 liter 15 Ghc We try our best to have all dishes available all the time despite our remote location. In case we do run out of (or lack some) Smoothie or Fresh Juice Per glass 8 Ghc ingredients, we will find a creative solution and serve you a delicious meal. Soft Drinks Per bottle 5 Ghc When the lodge is busy with guests (> 6 people), meals are Water Per 1.5l bottle 5 Ghc served in buffet style, but feel free to share preferences with us. Some meals take quite long to prepare, so please discuss HARD DRINKS possibilities with Philo if you are in a ‘fast-food mood’. Beer (Club, Star, Guinness) Per 650 ml 8 Ghc Midunu! Wine (red or white) Per bottle 45 Ghc Akpeteshie (local gin) Per tot 3 Ghc Feel free to make yourself a tea or a coffee or take a drink from the fridge. Akpeteshie tonic Per 1.5l bottle 8 Ghc Just write your names and your Takai (coffee/chocolate liquor) Per tot 5 Ghc consumptions on the list. -

Ghana: Changing Values/ Changing Technologies

CULTURAL HERITAGE AND CONTEMPORARY CHANGE SERIES II, AFRICA, VOLUME 5 GHANA: CHANGING VALUES/ CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES Ghanian Philosophical Studies, II Edited by Helen Lauer The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2000 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Ghana: changing values/changing technology: Ghanaian philosophical studies / edited by Helen Lauer. p.cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series II, Africa; vol. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Technology—Ghana. 2. Technology—Philosophy. I. Lauer, Helen. II. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, II. III. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, two. IV. Title: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, 2. V. Series. T28.G4C37 1999 99-37506 338.966706—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-56518-144-1 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iii Preface George F. McLean xiii Introduction Helen Lauer 1 PART I. CULTURE AND CHANGE Chapter I. Culture: the Human Factor in African Development Kofi Anyidoho 19 Chapter II. Modern Technology, Traditional Mysticism and Ethics in Akan Culture George P. Hagan 31 Chapter III. Traditional Ga and Dangme Attitudes towards Change and Modernization Joshua N. Kudadjie 53 PART II. SOCIETY AND CHANGES OF VALUES Chapter IV. Counterproductive Socioeconomic Management in Ghana A.O. Abudu 79 Chapter V. Informalization and Ghanaian Politics Kwame A. Ninsin 113 Chapter VI. Manipulation of the Mass Media in Ghana’s Recent Political Experience Joseph Osei 139 PART III. TECHNOLOGY AND HUMAN CHANGE Chapter VII. Plant Biodiversity, Herbal Medicine, Intellectual Property Rights and Industrially Developing Countries: Socio-economic, Ethical and Legal Implications Ivan Addae-Mensah 165 Chapter VIII. -

T He S Ta Te and T He D Ev Elo P M En T O F S M a Ll-S C a Le in D U Stry in G Hana Sin Ce C

R a jiv B a l l The State and The Developm ent of Sm all-scale Industry in Ghana since c.1945 A T h e s i s s u b m i t t e d f o r F i n a l E x a m i n a t i o n f o r t h e De g r e e o f D o c t o r o f P h i l o s o p h y De p a r t m e n t o f E c o n o m ic H is t o r y L o n d o n S c h o o l o f E c o n o m ic s a n d P o l it ic a l S c ie n c e S e p t e m b e r 1997 UMI Number: U615B61 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615361 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

Review of the History of Distilled Liquor and Its Impact on the Kumasi People of Ghana

Review of the History of Distilled Liquor and Its Impact on the Kumasi People of Ghana Samuel ADU-GYAMFI1 Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi-Ghana [email protected], Wilhemina Joselyn DONKOH2 President, Garden City University College, Kumasi-Ghana, [email protected] Dinah Ntim Akosua GYAMFUAH3 Department of History and Political Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi-Ghana [email protected] Abstract Socio-cultural changes in the pattern of development of a group of people often occur when there is an introduction of foreign cultures. The annexation of Gold Coast brought the Asante Empire under British rule, and from the beginning of the twentieth century Gold Coast witnessed a total transformation of the economy from it subsistence nature to a cash economy. Economic changes associated with diversification and rapid expansion of Gold Coast export mitigated for a demand in labour force. However, the research focused on the people of Kumasi and using the Winick theory of alcohol dependency sought to unveil the socio-cultural changes that occurred within the period under review. Furthermore, with the use of qualitative narrative, interviews, secondary and primary data, the research was undertaken and findings revealed some changes in customs, values, and lifestyle of individuals in the community. It further indicated the role played by colonial influence and administration’s reliance on imported alcohol coupled with the introduction of a new kind of local gin (akpeteshie). It was also discovered that, European influence contributed greatly to changes that occurred in the social and cultural uses of distilled liquor in Kumasi. -

The Africa Project a PROGRAM of the ASSOCIATION of YALE ALUMNI

The Africa Project A PROGRAM OF THE ASSOCIATION OF YALE ALUMNI YAMORANSA AND ACCRA, GHANA July 27 – August 7, 2012 (Extension to August 10 – North Ghana) Half NEWSLETTER June 2012 Table of Contents FUN STUFF ............................................................................................................... 1 HARD WORK ........................................................................................................... 1 CHOW TIME! ............................................................................................................ 2 ACTION ITEMS OR WHAT YOU NEED TO DO NOW! ....................................... 4 Fun stuff The purpose of this Newsletter is to let you know that iif you are in town, sometime within the next week you should receive your package of travel goodies from AYA. It should contain: - A hat - A tourbook - A Participant Directory - A bag - Two Luggage Tags - And a Packing List Please bring all the items except the packing list with you on the trip – naturally the luggage tags should be put to their proper use right away. If you have not received the package by July 1, please contact Joao at [email protected] to let him know. Hard Work Thank you to all of those, which is most of you, who have been working so hard to prepare for your projects. Today I received a long list of students – this will be amazing. I will send the list to the education and athletics groups as I soon as I know from Kwame whether we make the class sections or if they will do that. If I haven’t heard by tomorrow, I will send it as is (don’t be overwhelmed – this is opportunity!) Keep those emails flying… The Africa Project NEWSLETTER #5 June 2012 Chow Time! What kind of food will you be eating in Ghana? Wikipedia can tell you all about it with some small annotations from us… There are diverse traditional dishes from each ethnic group, tribe and clan from the north to the south and from the east to west. -

Good Work Done.Pdf

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (KNUST) COLLEGE OF SCIENCES FACULTY OF BIOSCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY EVIDENCE OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES LACED WITH CANNABIS SOLD IN BARS IN THE ACCRA METROPOLIS THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF AN MSc IN FORENSIC SCIENCE KAFUI NKROMA APRIL, 2018 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MSc. And that, to the best of my knowledge; it contains no material previously published by another person or material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Kafui Nkroma ………………………… ………………………… (PG4429115) Signature Date Certified By: Dr Samson Pandam Salifu ………………………… ………………………… (Supervisor) Signature Date Dr Peter Twumasi ………………………… ………………………… (Head of Department) Signature Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly, am most grateful to the almighty God whose strength and inspiration has seen me through this study. I wish to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor Dr Pandam Samson Salifu, and Dr Christpher Larbie for their patience, guidance and constructive criticism which made it possible for the completion of this thesis. I thank the Head and entire staff of the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology of KNUST and Forensic tutors for their encouragement. My special gratitude goes to Mr James Ataki, and Dr F.C.Mills-Robertson who took part in making this endeavor possible. I would like to acknowledge Dr Paul Fosu and Mr Peter Ashittey and the entire staff of Standards Authority for granting me access to their facilities to enable me complete my thesis. -

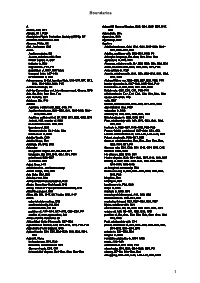

Boundaries 1

Boundaries A Agbovi IV, Nene of Kpetoe, G32, G34, G36–G37, K17, Abéné, A40, G17 N18 Ablode, K17, K20 Agbrodrafo, B15 Aboriginies Rights Protection Society (ARPS), D7 Agoe clan, B19 Abraham Commission, K33 Agomlanyi, G32 Abrams, Philip, A5 Agotime Abri, Asafoatse, G35 Adaklu land case, G34_G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– Accra N19, N26–N27, P20 Agotime origins, B8 Adaklu, realitions with, B12–B13, N19, P4 Asante, relations with, B29 Adangbe language, B8, G40, N15, N19, N28 British traders in, C37 agriculture in, E29, M11 industry in, K25 Akwamu, relations with, B7, B22–B23, B25, B28, B31 migration to, F21, P9 Ando, relations with, G35, G39, N16, N19, P20 population of, M47, M47 table Anlo settlers in, P20 transport links, F37–F38 Asante, relations with, B14, B23, B28–B30, B31, C36, in World War II, H10 G31, G39 Acheampong, Lt-Col. Ignatius Kutu, L18–L19, M7, M12, Atukpui-Nyive war, B23–B25, B27, B28, N22, P19 M14, M21–M22, M49, P15 border dynamics in, N37–N44, N45–N46, P10 Achimota College, K3 boundaries of, B20, B30, B31, E30, G29 Ad Hoc Committee on Union Government, Ghana, M20 British rule, C37, C38, C41, E35–E41 Ada, B8, B17, B22–B23, F26 chieftancies in, E27, E31–E34, K16–K18, N25, N40 Ada Manche, C37 cocoa cultivation, F25 Adabara, Etu, F44 cults, B27 Adaklu Danish, relations with, B13–B16, B17–B18, B25 Agotime, conflict with, B22, C36, P4 dipo initiation rites, N30 Agotime land case, G34–G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– education in, N42 N19, N26–N27 ethnicity of, B26, G28, G40, G41, N44 Agotime, settlement of, B7, B12–B13, B20, G32, G33 Ewe language in, G26, G40, N19 Ankrah, H.B.