Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikolai Dolgorukov

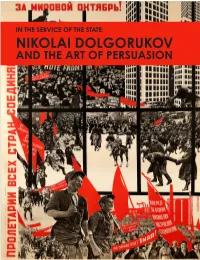

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Faith, Reason, and Social Thought in the Young Vladimir Segeevich

“A Foggy Youth”: Faith, Reason, and Social Thought in the Young Vladimir Segeevich Solov’ev, 1853-1881 by Sean Michael James Gillen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 2 May 2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: David MacLaren McDonald, Professor of History Francine Hirsch, Professor of History Judith Deutsch Kornblatt, Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures Rudy Koshar, Professor of History Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, Professor of History © Copyright by Sean Michael James Gillen 2012 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents i Abstract Table of Contents i-ii Acknowledgments iii-iv Abreviations v Introduction: Vladimir Solov’ev in Historiography—The Problem of the “Symbolist Conceit” 1-43 Chapter 1: Solov’ev’s Moscow: Social Science, Civic Culture, and the Problem of Education, 1835-1873 44-83 Chapter 2: The Genesis of Solov’ev’s “Conscious Faith Founded on Reason:” History, Religion, and the Future of Mankind, 1873-1874 84-134 Chapter 3: Practical Philosophy and Solov’ev Abroad: Socialism, Ethics, and Foreign Policy—London and Cairo, 1875-1876 135-167 Chapter 4: The Russo-Turkish War and the Moscow Slavic Benevolent Committee: Statehood, Society, and Religion—June 1876-February 1877 168-214 Chapter 5: Chteniia o bogochelovechestve—Christian Epic in a Theistic Mode: Theism, Morality, and Society, 1877-1878 215-256 Conclusion: 257-266 Bibliography 267-305 ii Acknowledgments iii This dissertation has been supported by both individuals and institutions. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

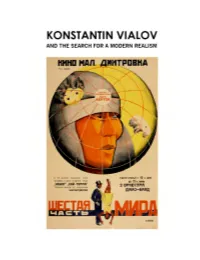

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Russia – Art Resistance and the Conservative-Authoritarian Zeitgeist

i Russia – Art Resistance and the Conservative- Authoritarian Zeitgeist This book explores how artistic strategies of resistance have survived under the conservative- authoritarian regime which has been in place in Russia since 2012. It discusses the conditions under which artists work as aesthetics change and the state attempts to define what constitutes good taste. It examines the approaches artists are adopting to resist state oppression and to question the present system and attitudes to art. The book addresses a wide range of issues related to these themes, considers the work of individual artists and includes some discussion of contemporary theatre as well as the visual arts. Lena Jonson is Associate Professor and a Senior Associate Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs. Andrei Erofeev is a widely published art historian, curator, and former head of the contemporary art section of the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. ii Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series Series url: www.routledge.com/ Routledge- Contemporary- Russia- and- Eastern- Europe- Series/ book- series/ SE0766 71 EU- Russia Relations, 1999– 2015 From Courtship to Confrontation Anna- Sophie Maass 72 Migrant Workers in Russia Global Challenges of the Shadow Economy in Societal Transformation Edited by Anna- Liisa Heusala and Kaarina Aitamurto 73 Gender Inequality in the Eastern European Labour Market Twenty- five Years of Transition since the Fall of Communism Edited by Giovanni Razzu 74 Reforming the Russian Industrial Workplace -

Celebrating Suprematism: New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir

Celebrating Suprematism Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks (The Johns Hopkins University) Christina Lodder (University of Kent) Volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Celebrating Suprematism New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich Edited by Christina Lodder Cover illustration: Installation photograph of Kazimir Malevich’s display of Suprematist Paintings at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, 0.10 (Zero-Ten), in Petrograd, 19 December 1915 – 19 January 1916. Photograph private collection. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lodder, Christina, 1948- editor. Title: Celebrating Suprematism : new approaches to the art of Kazimir Malevich / edited by Christina Lodder. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2019] | Series: Russian history and culture, ISSN1877-7791 ; Volume 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN2018037205 (print) | LCCN2018046303 (ebook) | ISBN9789004384989 (E-book) | ISBN 9789004384873 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich, 1878-1935–Criticism and interpretation. | Suprematism in art. | UNOVIS (Group) Classification: LCCN6999.M34 (ebook) | LCCN6999.M34C452019 (print) | DDC 700.92–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037205 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN1877-7791 ISBN 978-90-04-38487-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-38498-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Music and Russian Identity in War and Revolution, 1914–22

Music and Russian Identity in War and Revolution, 1914–22 Rebecca Mitchell In January 1915 the weekly Moscow journal Muzyka unveiled a new cover logo: an unsheathed sword whose upright hilt formed the shape of a Christian cross and whose blade was framed by a musical lyre. This single image provided a visual encapsulation of three interlocking themes that dominated Russian- language discourse in the early months of the Great War: music, battle, and the spiritual mission of Holy Russia.1 (See fig. 47 in gallery of illustrations following page 178.) Immediately after the outbreak of war in 1914, Muzyka’s editor, Vladimir V. Derzhanovskii, asserted that music was to play an active role in the conflict. How, he asked, were his readers (as Russian musicians) to “react to these great events experienced by the motherland” and “fulfill their duty” to society? How would they defend “Russian national culture”? While some might be called to “exchange their lyre for a sword,” Derzhanovskii intimated that the vast majority faced the difficult mission of redoubling their important cultural work amid total war.2 The problem of Russian musical identity in the context of a multiethnic empire was to play a central role in defining just what that mission was to be. While the role of nationalism in Russian music has long been a topic of study, the relationship between Russian national (russkii) and imperial (ros- siiskii) identity, particularly in the midst of war and revolution, deserves closer consideration.3 With the outbreak of war, loyalty to one’s ethnic background, one’s country of citizenship, or to a universal, shared culture of humanity emerged as an urgent problem for musicians, music critics, and audiences.4 1 The original logo employed by Muzyka at the journal’s inception in 1910 was a lyre; in 1914 this was altered to Russian folk instruments. -

View, Is Ineffective

Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: Dædalus on sex Joan Roughgarden, Terry Castle, Steven Marcus, Elizabeth Benedict, Brian Charlesworth, Lawrence Cohen, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Tim Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Birkhead, Catharine MacKinnon, Margo Jefferson, and Stanley A. Corngold Winter 2007 on capitalism Joyce Appleby, John C. Bogle, Lucian Bebchuk, Robert W. Fogel, Winter 2007: on nonviolence & violence Winter 2007: on nonviolence & democracy Jerry Z. Muller, Richard Epstein, Benjamin M. Friedman, John Dunn, Robin Blackburn, and Gerhard Loewenberg on William H. McNeill Violence & its historical limits 5 nonviolence Steven A. LeBlanc Why warfare? 13 & violence on life Anthony Kenny, Thomas Laqueur, Shai Lavi, Lorraine Daston, Paul Jonathan Schell Rabinow, Robert P. George, Robert J. Richards, Nikolas Rose, John & Robert S. Boynton People’s power vs. nuclear power 22 Broome, Jeff McMahan, and Adrian Woolfson Mark Juergensmeyer Gandhi vs. terrorism 30 Neil L. Whitehead Violence & the cultural order 40 on the public interest William Galston, E. J. Dionne, Jr., Seyla Benhabib, Jagdish Bhagwati, Adam Wolfson, Lance Taylor, Gary Hart, Nathan Glazer, Robert N. Tzvetan Todorov Avant-gardes & totalitarianism 51 Bellah, Nancy Rosenblum, Amy Gutmann, and Christine Todd Adam Michnik The Ultras of moral revolution 67 Whitman Cindy D. Ness The rise in female violence 84 Mia Bloom Female suicide bombers 94 on nature Leo Marx, William Cronon, Cass Sunstein, Daniel Kevles, Bill Robert H. Mnookin Negotiating conflict: Belgium & Israel 103 McKibben, Harriet Ritvo, Gordon Orians, Camille Parmesan, Margaret Schabas, and Philip Tetlock & Michael Oppenheimer James G. Blight & janet M. Lang Robert McNamara: then & now 120 on cosmopolitanism Martha C. -

Vanguardia Y Propaganda Avant-Garde and Propaganda

AAFF_ARCHIVO LAFUENTE II.indd 4 14/5/19 19:33 AAFF_ARCHIVO LAFUENTE II.indd 1 14/5/19 19:33 AAFF_ARCHIVO LAFUENTE II.indd 2 14/5/19 19:33 Vanguardia y propaganda Avant-Garde and Propaganda Libros y revistas rusos Soviet Books and Magazines del Archivo Lafuente in the Archivo Lafuente 1913–1941 1913–1941 AAFF_ARCHIVO LAFUENTE II.indd 3 14/5/19 19:33 AAFF_ARCHIVO LAFUENTE II.indd 4 14/5/19 19:33 Índice Contents Introducción Foreword 7 La vanguardia rusa y el realismo 17 The Russian Avant-Garde and Socialist socialista en el Archivo Lafuente Realism in the Archivo Lafuente por Beatriz García Cossío by Beatriz García Cossío 9 De las «palabras en libertad» 19 From “Words in Freedom” to al «servicio de la revolución» the “Service of the Revolution” por Oliva María Rubio by Oliva María Rubio Ensayos Essays 29 Las palabras se perciben con la vista: 53 Words Are Perceived with the Eyes: tipografía y constructivismo ruso Typography and Russian Constructivism por Raquel Pelta Resano by Raquel Pelta Resano 35 El fotomontaje en libros de edición masiva: 59 Photomontage in the Mass-Book: algunos aspectos de la práctica constructivista Some Aspects of Constructivist Practice por Iveta Derkusova by Iveta Derkusova 43 L a urss en construcción: 65 ussr in Construction: el cambio en el régimen visual Changing Visual Regimes por Evgeny Dobrenko by Evgeny Dobrenko Libros y revistas rusos del Soviet Books and Magazines in Archivo Lafuente (1913–1941) the Archivo Lafuente (1913–1941) 77 Tipografía 77 Typography 183 Fotografía y fotomontaje 183 Photography and -

Berdyaev's Moscow: a Philosophical Investigation of Local History

Russian Studies in Philosophy ISSN: 1061-1967 (Print) 1558-0431 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/mrsp20 Berdyaev's Moscow: A Philosophical Investigation of Local History Aleksei A. Kara-Murza To cite this article: Aleksei A. Kara-Murza (2015) Berdyaev's Moscow: A Philosophical Investigation of Local History, Russian Studies in Philosophy, 53:4, 338-351, DOI: 10.1080/10611967.2015.1123062 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10611967.2015.1123062 Published online: 21 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=mrsp20 Download by: [North Carolina State University], [Professor Marina Bykova] Date: 21 April 2016, At: 13:38 Russian Studies in Philosophy, vol. 53, no. 4, 2015, pp. 338–351. q 2015 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1061-1967 (print)/ISSN 1558-0431 (online) DOI: 10.1080/10611967.2015.1123062 ALEKSEI A. KARA-MURZA Berdyaev’s Moscow: A Philosophical Investigation of Local History Based on considerable factual material, the author establishes Berdyaev’s Moscow addresses and shows how Berdyaev’s Moscow environment related to different stages of his philosophical work and public life. On Nikolai Berdyaev’s 140th anniversary (1874–1948), Moscow’s philosophers and local historians once again noted that Berdyaev, who was born in Kiev and died in Clamart, near Paris, was in large part a “Muscovite.”1 Moscow’s intellectual environment played a unique role in his life, especially the final years before Berdyaev’s expulsion from Russia by the Bolsheviks.