View, Is Ineffective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex Chromosomes: Evolution of Beneficial to Males but Harmful to Females, and the Other Has the the Weird and Wonderful Opposite Effect

Dispatch R129 microtubule plus ends is coupled to of kinesin-mediated transport of Bik1 1The Scripps Research Institute, microtubule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 144, (CLIP-170) regulates microtubule Department of Cell Biology, 10550 99–112. stability and dynein activation. Dev. Cell 11. Arnal, I., Karsenti, E., and Hyman, A.A. 6, 815–829. North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, (2000). Structural transitions at 14. Andersen, S.S., and Karsenti, E. (1997). California 92037, USA. microtubule ends correlate with their XMAP310: a Xenopus rescue-promoting E-mail: [email protected] dynamic properties in Xenopus egg factor localized to the mitotic spindle. J. 2Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, extracts. J. Cell Biol. 149, 767–774. Cell Biol. 139, 975–983. Department of Cellular and Molecular 12. Busch, K.E., Hayles, J., Nurse, P., and 15. Schroer, T.A. (2004). Dynactin. Annu. Brunner, D. (2004). Tea2p kinesin is Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 759–779. Medicine, CMM-E Rm 3052, 9500 involved in spatial microtubule 16. Vaughan, P.S., Miura, P., Henderson, M., Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, organization by transporting tip1p on Byrne, B., and Vaughan, K.T. (2002). A USA. E-mail: [email protected] microtubules. Dev. Cell 6, 831–843. role for regulated binding of p150(Glued) 13. Carvalho, P., Gupta, M.L., Jr., Hoyt, M.A., to microtubule plus ends in organelle and Pellman, D. (2004). Cell cycle control transport. J. Cell Biol. 158, 305–319. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.010 Sex Chromosomes: Evolution of beneficial to males but harmful to females, and the other has the the Weird and Wonderful opposite effect. -

Faith and Thought

1981 Vol. 108 No. 3 Faith and Thought Journal of the Victoria Institute or Philosophical Society of Great Britain Published by THE VICTORIA INSTITUTE 29 QUEEN STREET, LONDON, EC4R IBH Tel: 01-248-3643 July 1982 ABOUT THIS JOURNAL FAITH AND THOUGHT, the continuation of the JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF THE VICTORIA INSTITUTE OR PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN, has been published regularly since the formation of the Society in 1865. The title was changed in 1958 (Vol. 90). FAITH AND THOUGHT is now published three times a year, price per issue £5.00 (post free) and is available from the Society's Address, 29 Queen Street, London, EC4R 1BH. Back issues are often available. For details of prices apply to the Secretary. FAITH AND THOUGHT is issued free to FELLOWS, MEMBERS AND ASSOCIATES of the Victoria Institute. Applications for membership should be accompanied by a remittance which will be returned in the event of non-election. (Subscriptions are: FELLOWS £10.00; MEMBERS £8.00; AS SOCIATES, full-time students, below the age of 25 years, full-time or retired clergy or other Christian workers on small incomes £5.00; LIBRARY SUBSCRIBERS £10.00. FELLOWS must be Christians and must be nominated by a FELLOW.) Subscriptions which may be paid by covenant are accepted by Inland Revenue Authorities as an allowable expense against income tax for ministers of religion, teachers of RI, etc. For further details, covenant forms, etc, apply to the Society. EDITORIAL ADDRESS 29 Almond Grove, Bar Hill, Cambridge, CB3 8DU. © Copyright by the Victoria Institute and Contributors, 1981 UK ISSN 0014-7028 FAITH 1981 AND Vol. -

Profile of Brian Charlesworth

PROFILE Profile of Brian Charlesworth Jennifer Viegas my future wife, Deborah Maltby, there. We Science Writer owe a huge amount to each other intellectually, and much of my best work has been done in ” National Academy of Sciences foreign asso- later moved to London, but Charlesworth’s collaboration with her, says Charlesworth. ciate Brian Charlesworth has been at the interest in nature remained. Charlesworth continued his studies at forefront of evolutionary genetics research for At age 11, he entered the private Haber- Cambridge, earning a PhD in genetics in 1969. the last four decades. Using theoretical ideas dashers’ Aske’s Boys’ School, which he at- This was followed by 2 years of postdoctoral to design experiments and experimental data tended on a local government scholarship. work at the University of Chicago, where “ as a stimulant for the development of theory, “It had well-equipped labs and some very Richard Lewontin served as his adviser. He Charlesworth investigates fundamental life good teachers,” Charlesworth says. He read was a wonderful role model, with a penetrat- processes. His work has contributed to im- extensively, visited London museums, and ing intellect and a readiness to argue about ” “ proved understanding of molecular evolution attended public lectures at University Col- almost everything, Charlesworth says. Ihave and variation, the evolution of genetic and lege London. His early role models were probably learnt more about how to do science ” sexual systems, and the evolutionary genetics physics and biology teacher Theodore Sa- from him than anyone else. Population of life history traits. In 2010, Charlesworth vory and biology teacher Barry Goater. -

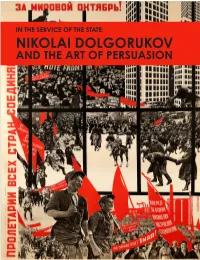

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Evolutionary Genetics Quantified Nature Genetics E-Mail: State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

BOOK REVIEW undergraduate life sciences curricula and into the knowledge base of Evolutionary genetics quantified life science researchers. Brian and Deborah Charlesworth have drawn Elements of Evolutionary Genetics on their extensive expertise in these fields to produce a textbook that is a comprehensive, up-to-date treatise on the field of evolutionary Brian Charlesworth & genetics. Deborah Charlesworth Elements of Evolutionary Genetics is part text, part monograph and part review. It is divided into ten chapters. The first section of the text- Roberts and Company Publishers, 2010 book, including the first four chapters, describes genetic variability 768 pp., hardcopy, $80 and its measurement in inbreeding and outbred populations, classic ISBN 9780981519425 selection theory at a single locus and for quantitative traits, the evolu- tionary genetics of adaptation, and migration-selection and mutation- Reviewed by Trudy F C Mackay selection balance. The fifth chapter introduces the complication of finite population size and the probability distributions of allele fre- quencies under the joint actions of mutation, selection and drift. The remaining chapters discuss the neutral theory of molecular evolution, Evolutionary genetics is the study of how genetic processes such as population genetic tests of selection, population and evolutionary mutation and recombination are affected by the evolutionary forces of genetics in subdivided populations, multi-locus theory, the evolution selection, genetic drift and migration to produce patterns of genetic of breeding systems, sex ratios and life histories, and selected top- variation at segregating loci and for quantitative traits, within and ics in genome evolution. The topics are illustrated throughout with between populations and over short and long timescales. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

Veldman, Harold E and Pearl Oral History Interview: Old China Hands Oral History Project David M

Hope College Digital Commons @ Hope College Old China Hands Oral History Project Oral History Interviews 7-23-1976 Veldman, Harold E and Pearl Oral History Interview: Old China Hands Oral History Project David M. Vander Haar Nancy Swinyard Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/old_china Part of the Archival Science Commons, and the Oral History Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Vander Haar, David M. and Swinyard, Nancy, "Veldman, Harold E and Pearl Oral History Interview: Old China Hands Oral History Project" (1976). Old China Hands Oral History Project. Paper 14. http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/old_china/14 Published in: Old China Hands Oral History Project (former missionaries to China) (H88-0113), July 23, 1976. Copyright © 1976 Hope College, Holland, MI. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Oral History Interviews at Digital Commons @ Hope College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old China Hands Oral History Project by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Hope College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OLD CHINA HANDS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Dr. Harold E. and Mrs. Pearl Veldman This manuscript 1s authorized as tlopenll Hope College Archives Council Holland, Michigan 1977 ./ ,/ '''ii'.// ! ~~ / ><-.",- MISSION / • 001_,, .I 0loo,lOoo"--~_ / -~~ .l.-M__~ / .s....,. / / / ! Fig. 1 Dr. & Mrs. Harold Veldman Table of Contents Preface ...................... .. v Biographical Sketch and Summary of Contents .... .. vi Interview I ....... ............ .. 1 Index ..........•............ .. 32 1v Preface Interviewees: Dr. Harold and Mrs. Pearl Veldman Interview I: July 23, 1976 Dr. and Mrs. Veldman's home in Grand Rapids, Michigan Interviewers: Mr. David M. -

3161515331 Lp.Pdf

I Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey (München) Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie (Marburg) Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) 244 II III Paul A. Holloway Coping with Prejudice 1 Peter in Social-Psychological Perspective Mohr Siebeck IV Paul A. Holloway, born 1955; 1998 Ph.D. University of Chicago; 1998–2006 Assistant Professor and then Associate Professor of Religion, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama; 2006–2009 Lecturer then Senior Lecturer in Christian Origins, University of Glasgow; since 2009 Associate Professor of New Testament, School of Theology, Sewanee: The University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee. e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-151533-0 ISBN 978-3-16-149961-6 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra- phie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. © 2009 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduction, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Computersatz Staiger in Rottenburg/N., printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. V For Melissa, and for Chapney, Abigail, Callie, and Lillian VI VII Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to recall the encouragement and help I have received in researching and writing this book. First of all, I wish to thank Jörg Frey and Hans-Josef Klauck, the editors of Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testa- ment, for expressing their interest in the topic and issuing a contract at an early stage of my research. -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

1. Councillors & Officers List

Yeejleer³e je<ì^ieerle HetCe& peveieCeceve-DeefOevee³ekeÀ pe³e ns Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Hebpeeye, efmebOeg, iegpejele, cejeþe, NATIONAL ANTHEM OF INDIA êeefJe[, GlkeÀue, yebie, efJebO³e, efncee®eue, ³ecegvee, iebiee, Full Version G®íue peueeqOelejbie leJe MegYe veeces peeies, leJe MegYe DeeeqMe<e ceeies, Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka jaya he ieens leJe pe³eieeLee, Bharat-bhagya-vidhata peveieCe cebieueoe³ekeÀ pe³e ns, Punjab-Sindhu-Gujarata-Maratha Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Dravida-Utkala-Banga pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e pe³e pe³e, pe³e ns ~~ Vindhya-Himachala-Yamuna-Ganga mebef#eHle Uchchala-jaladhi-taranga peveieCeceve-DeefOevee³ekeÀ pe³e ns Tava Shubha name jage, tava subha asisa mage Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Gahe tava jaya-gatha pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e ns, Jana-gana-mangala-dayaka jaya he pe³e pe³e pe³e, pe³e ns ~~ Bharat-bhagya-vidhata Jaya he, jaya he, jaya he, Jaya jaya jaya jaya he. Short version Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka jaya he Bharat-bhagya-vidhata Jaya he, Jaya he, jaya he jaya jaya jaya, jaya he, PERSONAL MEMORANDUM Name ............................................................................................................................................................................ Office Address .................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................ .................................................... .............................................................................................. -

The Structure of Evolutionary Theory: Beyond Neo-Darwinism, Neo

1 2 3 The structure of evolutionary theory: Beyond Neo-Darwinism, 4 Neo-Lamarckism and biased historical narratives about the 5 Modern Synthesis 6 7 8 9 10 Erik I. Svensson 11 12 Evolutionary Ecology Unit, Department of Biology, Lund University, SE-223 62 Lund, 13 SWEDEN 14 15 Correspondence: [email protected] 16 17 18 19 1 20 Abstract 21 The last decades have seen frequent calls for a more extended evolutionary synthesis (EES) that 22 will supposedly overcome the limitations in the current evolutionary framework with its 23 intellectual roots in the Modern Synthesis (MS). Some radical critics even want to entirely 24 abandon the current evolutionary framework, claiming that the MS (often erroneously labelled 25 “Neo-Darwinism”) is outdated, and will soon be replaced by an entirely new framework, such 26 as the Third Way of Evolution (TWE). Such criticisms are not new, but have repeatedly re- 27 surfaced every decade since the formation of the MS, and were particularly articulated by 28 developmental biologist Conrad Waddington and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. 29 Waddington, Gould and later critics argued that the MS was too narrowly focused on genes and 30 natural selection, and that it ignored developmental processes, epigenetics, paleontology and 31 macroevolutionary phenomena. More recent critics partly recycle these old arguments and 32 argue that non-genetic inheritance, niche construction, phenotypic plasticity and developmental 33 bias necessitate major revision of evolutionary theory. Here I discuss these supposed 34 challenges, taking a historical perspective and tracing these arguments back to Waddington and 35 Gould. I dissect the old arguments by Waddington, Gould and more recent critics that the MS 36 was excessively gene centric and became increasingly “hardened” over time and narrowly 37 focused on natural selection. -

The Outstanding Scientist, R.A. Fisher: His Views on Eugenics and Race

Heredity (2021) 126:565–576 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-00394-6 PERSPECTIVE The outstanding scientist, R.A. Fisher: his views on eugenics and race 1 2 3 4 5 Walter Bodmer ● R. A. Bailey ● Brian Charlesworth ● Adam Eyre-Walker ● Vernon Farewell ● 6 7 Andrew Mead ● Stephen Senn Received: 2 October 2020 / Revised: 2 December 2020 / Accepted: 2 December 2020 / Published online: 15 January 2021 © The Author(s) 2021. This article is published with open access Introduction aim of this paper is to conduct a careful analysis of his own writings in these areas. Our purpose is neither to defend nor R.A. Fisher was one of the greatest scientists of the 20th attack Fisher’s work in eugenics and views on race, but to century (Fig. 1). He was a man of extraordinary ability and present a careful account of their substance and nature. originality whose scientific contributions ranged over a very wide area of science, from biology through statistics to ideas on continental drift, and whose work has had a huge Fisher’s scientific achievements 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: positive impact on human welfare. Not surprisingly, some of his large volume of work is not widely used or accepted Contributions to statistics at the current time, but his scientific brilliance has never been challenged. He was from an early age a supporter of Fisher has been described as “the founder of modern sta- certain eugenic ideas, and it is for this reason that he has tistics” (Rao 1992). His work did much to enlarge, and then been accused of being a racist and an advocate of forced set the boundaries of, the subject of statistics and to estab- sterilisation (Evans 2020).