Soviet Epistemologies and the Materialist Ontology of Poor Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aleksandr Bogdanov and Systems Theory

Democracy & Nature, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2000 Aleksandr Bogdanov and Systems Theory ARRAN GARE ABSTRACT The signi cance and potential of systems theory and complexity theory are best appreciated through an understanding of their origins. Arguably, their originator was the Russian philosopher and revolutionary, Aleksandr Bogdanov. Bogdanov anticipated later developments of systems theory and complexity theory in his efforts to lay the foundations for a new, post-capitalist culture and science. This science would overcome the division between the natural and the human sciences and enable workers to organise themselves and their productive activity. It would be central to the culture of a society in which class and gender divisions have been transcended. At the same time it would free people from the deformed thinking of class societies, enabling them to appreciate both the limitations and the signi cance of their environments and other forms of life. In this paper it is argued that whatever Bogdanov’s limitations, such a science is still required if we are to create a society free of class divisions, and that it is in this light that developments in systems theory and complexity theory should be judged. Aleksandr Bogdanov, the Russian revolutionary, philosopher and scientist, has a good claim to being regarded as the founder of systems theory.1 His ‘tektology’, that is, his new science of organisation, not only anticipated and probably in uenced the ideas of Ludwig von Bertalanffy—who must have been familiar with his work,2 but anticipated many of the ideas of the complexity theorists. As Simona Poustlinik commented at a recent conference on Bogdanov: It is remarkable the extent to which Bogdanov anticipated the ideas which were to be developed in systems thinking later in the twentieth century. -

CV, Full Format

BENJAMIN PALOFF (1/15/2013) Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures 507 Bruce Street University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Ann Arbor, MI 48103 3040 MLB, 812 E. Washington (617) 953-2650 Ann Arbor, MI 48109 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 2007. M.A. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, November 2002. Dissertation: Intermediacy: A Poetics of Unfreedom in Interwar Russian, Polish, and Czech Literatures, a comparative treatment of metaphysics in Eastern European Modernism, 1918-1945. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan M.F.A. in Creative Writing/Poetry, April 2001. Thesis: Typeface, a manuscript of poems. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts B.A., magna cum laude with highest honors in field, Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 1999. Honors thesis: Divergent Narratives: Affinity and Difference in the Poetry of Zbigniew Herbert and Miroslav Holub, a comparative study. TEACHING Assistant Professor, Departments of Slavic Languages and Literatures and of Comparative Literature, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (2007-Present). Courses in Polish and comparative Slavic literatures, critical theory, and translation. Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Slavic Languages and Literatures: Jessica Zychowicz (Present), Jodi Grieg (Present), Jamie Parsons (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Comparative Literature: Sylwia Ejmont (2008), Corine Tachtiris (2011), Spencer Hawkins (Present), Olga Greco (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in other units: Ksenya Gurshtein (History of Art, 2011). MFA Thesis Committee in English/Creative Writing: Francine Harris (2011). Faculty Associate, Frankel Center for Jewish Studies (2009-Present); Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (2007-Present). Service: Steering Committee, Copernicus Endowment for Polish Studies (2007-Present). -

Nationality Issue in Proletkult Activities in Ukraine

GLOKALde April 2016, ISSN 2148-7278, Volume: 2 Number: 2, Article 4 GLOKALde is official e-journal of UDEEEWANA NATIONALITY ISSUE IN PROLETKULT ACTIVITIES IN UKRAINE Associate Professor Oksana O. GOMENIUK Ph.D. (Pedagogics), Pavlo TYchyna Uman State Pedagogical UniversitY, UKRAINE ABSTRACT The article highlights the social and political conditions under which the proletarian educational organizations of the 1920s functioned in the context of nationalitY issue, namelY the study of political frameworks determining the status of the Ukrainian language and culture in Ukraine. The nationalitY issue became crucial in Proletkult activities – a proletarian cultural, educational and literary organization in the structure of People's Commissariat, the aim of which was a broad and comprehensive development of the proletarian culture created by the working class. Unlike Russia, Proletkult’s organizations in Ukraine were not significantlY spread and ceased to exist due to the fact that the national language and culture were not taken into account and the contact with the peasants and indigenous people of non-proletarian origin was limited. KeYwords: Proletkult, worker, culture, language, policY, organization. FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM IN GENERAL AND ITS CONNECTION WITH IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL TASKS ContemporarY social transformations require detailed, critical reinterpreting the experiences of previous generations. In his work “Lectures” Hegel wrote that experience and history taught that peoples and governments had never learnt from history and did not act in accordance with the lessons that historY could give. The objective study of Russian-Ukrainian relations require special attention that will help to clarify the reasons for misunderstandings in historical context, to consider them in establishing intercommunication and ensuring peace in the geopolitical space. -

The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION FROM LENIN TO STALIN 1917-1929 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Hallett Carr | 9780333993095 | | | | | The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2nd edition PDF Book Philosophy Economic determinism Historical materialism Marx's dialectic Marx's method Philosophy of nature. Rosmer himself was conscripted in May and so could not attend the Zimmerwald conference held in Switzerland in September , when a first puny attempt was made to bring together the remnants of the antiwar Left. Aleksandr Kerensky, the prime…. Lenin was prepared to replace the Union he had originally proposed with a looser association in which the centralized powers might be limited to defense and international relations alone. Concerning the political disenfranchisement of the capitalist social-class in Bolshevik Russia, Lenin said that "depriving the exploiters of the franchise is a purely Russian question, and not a question of the dictatorship of the proletariat, in general. The Communists, therefore, are, on the one hand, practically the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the lines of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement. However, he ruled by terror, and millions of his own There are problems in the interpretation: Carr designates the overtrow of the Provisional Government as a coup; the inadequate control of workers in the nationalized industry does not derive from the inability of workers but from the given circumstances, etc. -

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art Presents: If Our Soup Can Could Speak: Mikhail Lifshitz and the Soviet Sixties

GARAGE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART PRESENTS: IF OUR SOUP CAN COULD SPEAK: MIKHAIL LIFSHITZ AND THE SOVIET SIXTIES March 7–May 13, 2018 This exhibition celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the scandalous publication of The Crisis of Ugliness by Soviet philosopher and art critic Mikhail Lifshitz. The book, which first appeared in 1968, was an anthology of polemical texts against Cubism and Pop Art—and one of the only intelligent discussions of modernism’s social context and overall logic available in the Soviet Union—making it popular even among those who disagreed with Lifshitz’s conclusions. The result of a three-year Garage Field Research project, If our soup can could speak takes as its starting point Lifshitz’s book and related writings to re-explore the vexed relations between so- called progressive art and politics in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as well as the motivations and implications of Lifshitz’s singular crusade against the modern classics. His appraisal of the crisis in twentieth-century art differs fundamentally from the standard attacks on modernism in government-issue Soviet art criticism, and in fact can be read as their direct critique. All the while, Lifshitz is in constant dialogue and debate with the century’s leading intellectuals in the West (Heidegger, Benjamin, Adorno, Horckheimer, Levi-Strauss, and others), searching for answers to the questions they posed from the perspective of someone with a unique inner experience of the Stalinist epoch’s revolutionary tragedy. The exhibition unfolds as a narrative of archival documents, art works, and text fragments, which are situated in a sequence of ten interiors that could be seen as spatial forms for landmark moments in the evolution of modernism, or in Lifshitz’s thinking. -

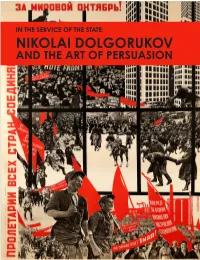

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

ALL-ROUND DEVELOPMENT of VLADIMIR LENIN's PERSONALITY Javed Akhter, Khair Muhammad and Naila Naz M.Phil Scholar, Department Of

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Method Vol.3, No.1, pp.23-34, March 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ALL-ROUND DEVELOPMENT OF VLADIMIR LENIN’S PERSONALITY Javed Akhter, Khair Muhammad and Naila Naz M.Phil Scholar, Department of English Literature and Linguistics, University of Balochistan Quetta Balochistan Pakistan ABSTRACT: The study investigates the personality of Vladimir Lenin, in the light of Stephen R. Covey’s suggested habits, expounded in his books, “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” and “The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to greatness”, following the most eminent Russian physiologist and psychologist I. P. Pavlov’s theory of classical behaviourism. Stephen R. Covey’s thought provoking and trend breaking book: “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” suggests seven habits and paradigms to become highly effective personality. He introduced the eighth habit in his innovative and challenging book “The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness.” Therefore, his suggested eight habits, and paradigms, which are based on I. P. Pavlov’s theory of classical behaviourism. This paper would use the popped up chunks of I. P. Pavlov’s behaviourist theory to analyse how the process of habit formation influenced the effective and great personalities of the world. Therefore, the present study will enable the readers to confront Pavlov’s classical behaviourist theory of habit formation through stimuli and responses. The readers are also expected to abandon the bad habits and adopt the good ones. These infrequent but subtle hints serve as a model of effective as well as great personality of the world. -

What Is Systems Theory?

What is Systems Theory? Systems theory is an interdisciplinary theory about the nature of complex systems in nature, society, and science, and is a framework by which one can investigate and/or describe any group of objects that work together to produce some result. This could be a single organism, any organization or society, or any electro-mechanical or informational artifact. As a technical and general academic area of study it predominantly refers to the science of systems that resulted from Bertalanffy's General System Theory (GST), among others, in initiating what became a project of systems research and practice. Systems theoretical approaches were later appropriated in other fields, such as in the structural functionalist sociology of Talcott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann . Contents - 1 Overview - 2 History - 3 Developments in system theories - 3.1 General systems research and systems inquiry - 3.2 Cybernetics - 3.3 Complex adaptive systems - 4 Applications of system theories - 4.1 Living systems theory - 4.2 Organizational theory - 4.3 Software and computing - 4.4 Sociology and Sociocybernetics - 4.5 System dynamics - 4.6 Systems engineering - 4.7 Systems psychology - 5 See also - 6 References - 7 Further reading - 8 External links - 9 Organisations // Overview 1 / 20 What is Systems Theory? Margaret Mead was an influential figure in systems theory. Contemporary ideas from systems theory have grown with diversified areas, exemplified by the work of Béla H. Bánáthy, ecological systems with Howard T. Odum, Eugene Odum and Fritj of Capra , organizational theory and management with individuals such as Peter Senge , interdisciplinary study with areas like Human Resource Development from the work of Richard A. -

“I Know That We the New Slaves”: an Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’S Yeezus

1 “I KNOW THAT WE THE NEW SLAVES”: AN ILLUSION OF LIFE ANALYSIS OF KANYE WEST’S YEEZUS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY MARGARET A. PARSON DR. KRISTEN MCCAULIFF - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 2 ABSTRACT THESIS: “I Know That We the New Slaves”: An Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’s Yeezus. STUDENT: Margaret Parson DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication Information and Media DATE: May 2017 PAGES: 108 This work utilizes an Illusion of Life method, developed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001) to analyze the 2013 album Yeezus by Kanye West. Through analyzing the lyrics of the album, several major arguments are made. First, Kanye West’s album Yeezus creates a new ethos to describe what it means to be a Black man in the United States. Additionally, West discusses race when looking at Black history as the foundation for this new ethos, through examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone’s rhetoric, references to racist cartoons and movies, and discussion of historical events such as apartheid. West also depicts race through lyrics about the imagined Black male experience in terms of education and capitalism. Second, the score of the album is ultimately categorized and charted according to the structures proposed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001). Ultimately, I argue that Yeezus presents several unique sounds and emotions, as well as perceptions on Black life in America. 3 Table of Contents Chapter One -

Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, Platonov and the Fragile Absolute of Russian Modernity

Three Easy Pieces: Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, Platonov and the Fragile Absolute of Russian Modernity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945016 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Three Easy Pieces: Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, Platonov and the Fragile Absolute of Russian Modernity A dissertation presented by Alexandre Gontchar to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2017 ©2017– Alexandre Gontchar All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: William M. Todd Alexandre Gontchar Three Easy Pieces: Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, Platonov and the Fragile Absolute of Russian Modernity Abstract This dissertation shows how three Russian authors estranged and challenged the notion of human freedom as self-determination—the idea that meaningful self-authorship is possible in view of the finitude that every human being embodies under different aspects of his existence, such as the individual and collective awareness of the inevitability of death, as well as the narrative inclusion of any existential project within multiple contexts of history, culture, and language, all of which are always given already. At first glance to be free is to transcend these multiple limits. -

Introduction 11. I Have Approached This Subject in Greater Detail in J. D

NOTES Introduction 11. I have approached this subject in greater detail in J. D. White, Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism (Basingstoke and London, 1996). 12. V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38, p. 180. 13. K. Marx, Grundrisse, translated by M. Nicolaus (Harmondsworth, 1973), p. 408. 14. N. I. Ziber, Teoriia tsennosti i kapitala D. Rikardo v sviazi s pozdneishimi dopolneniiami i raz"iasneniiami. Opyt kritiko-ekonomicheskogo issledovaniia (Kiev, 1871). 15. N. G. Chernyshevskii, ‘Dopolnenie i primechaniia na pervuiu knigu politicheskoi ekonomii Dzhon Stiuarta Millia’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 3 (Geneva, 1869); ‘Ocherki iz politicheskoi ekonomii (po Milliu)’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 4 (Geneva, 1870). Reprinted in N. G. Chernyshevskii, Polnoe sobranie sochineniy, Vol. IX (Moscow, 1949). 16. Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vols XI–XVI. 17. M. M. Kovalevskii, Obshchinnoe zemlevladenie, prichiny, khod i posledstviia ego razlozheniia (Moscow, 1879). 18. Marx to the editorial board of Otechestvennye zapiski, November 1877, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 196–201. 19. Marx to Zasulich, 8 March 1881, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 346–73. 10. It was published in the journal Vestnik Narodnoi Voli, no. 5 (1886). 11. D. Riazanov, ‘V Zasulich i K. Marks’, Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vol. 1 (1924), pp. 269–86. 12. N. F. Daniel'son, ‘Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshch- estvennogo khoziaistva’, Slovo, no. 10 (October 1880), pp. 77–143. 13. N. F. Daniel'son, Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshchestvennogo khozi- aistva (St Petersburg, 1893). 14. V. V. Vorontsov, Sud'by kapitalizma v Rossii (St Petersburg, 1882). -

Peter Weiss. Andrei Platonov. Ragnvald Blix. Georg Henrik Von Wright. Adam Michnik

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. March 2011. Vol IV:1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Södertörn University, Stockholm FEATURE. Steklov – Russian BALTIC temple of pure thought W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S COPING WITH TRANSITIONS PETER WEISS. ANDREI PLATONOV. RAGNVALD BLIX. GEORG HENRIK VON WRIGHT. ADAM MICHNIK. SLAVENKA DRAKULIĆ. Sixty pages BETRAYED GDR REVOLUTION? / EVERYDAY BELARUS / WAVE OF RELIGION IN ALBANIA / RUSSIAN FINANCIAL MARKETS 2short takes Memory and manipulation. Transliteration. Is anyone’s suffering more important than anyone else’s? Art and science – and then some “IF YOU WANT TO START a war, call me. Transliteration is both art and science CH I know all about how it's done”, says – and, in many cases, politics. Whether MÄ author Slavenka Drakulić with a touch царь should be written as tsar, tzar, ANNA of gallows humor during “Memory and czar, or csar may not be a particu- : H Manipulation: Religion as Politics in the larly sensitive political matter today, HOTO Balkans”, a symposium held in Lund, but the question of the transliteration P Sweden, on December 2, 2010. of the name of the current president This issue of the journal includes a of Belarus is exceedingly delicate. contribution from Drakulić (pp. 55–57) First, and perhaps most important: in which she claims that top-down gov- which name? Both the Belarusian ernance, which started the war, is also Аляксандр Лукашэнка, and the Rus- the path to reconciliation in the region. sian Александр Лукашенко are in use. Balkan experts attending the sympo- (And, while we’re at it, should that be sium agree that the war was directed Belarusian, or Belarussian, or Belaru- from the top, and that “top-down” is san, or Byelorussian, or Belorussian?) the key to understanding how the war BW does not want to take a stand on began in the region.