Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, Platonov and the Fragile Absolute of Russian Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV, Full Format

BENJAMIN PALOFF (1/15/2013) Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures 507 Bruce Street University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Ann Arbor, MI 48103 3040 MLB, 812 E. Washington (617) 953-2650 Ann Arbor, MI 48109 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 2007. M.A. in Slavic Languages and Literatures, November 2002. Dissertation: Intermediacy: A Poetics of Unfreedom in Interwar Russian, Polish, and Czech Literatures, a comparative treatment of metaphysics in Eastern European Modernism, 1918-1945. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan M.F.A. in Creative Writing/Poetry, April 2001. Thesis: Typeface, a manuscript of poems. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts B.A., magna cum laude with highest honors in field, Slavic Languages and Literatures, June 1999. Honors thesis: Divergent Narratives: Affinity and Difference in the Poetry of Zbigniew Herbert and Miroslav Holub, a comparative study. TEACHING Assistant Professor, Departments of Slavic Languages and Literatures and of Comparative Literature, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (2007-Present). Courses in Polish and comparative Slavic literatures, critical theory, and translation. Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Slavic Languages and Literatures: Jessica Zychowicz (Present), Jodi Grieg (Present), Jamie Parsons (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in Comparative Literature: Sylwia Ejmont (2008), Corine Tachtiris (2011), Spencer Hawkins (Present), Olga Greco (Present). Doctoral Dissertation Committees in other units: Ksenya Gurshtein (History of Art, 2011). MFA Thesis Committee in English/Creative Writing: Francine Harris (2011). Faculty Associate, Frankel Center for Jewish Studies (2009-Present); Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies (2007-Present). Service: Steering Committee, Copernicus Endowment for Polish Studies (2007-Present). -

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia © 2014 Brad Alexander Gordon A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi April, 2014 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Joshua First Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Dr. Valentina Iepuri 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………p. 3 Part I: Interwar Émigrés and Their Literary Contributions Introduction: The Russian Intelligentsia and the National Question………………….............................................................................................p. 4 Chapter 1: Russia’s Eschatological Quest: Longing for the Divine…………………………………………………………………………………p. 14 Chapter 2: Nature, Death, and the Peasant in Russian Literature and Art……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 26 Chapter 3: Tsvetaeva’s Tragedy and Tolstoi’s Triumph……………………………….........................................................................p. 36 Part II: The Émigrés Return Introduction: Nostalgia’s Role in Contemporary Literature and Film……………………………………………………………………………………p. 48 Chapter 4: “Old Russia” in Contemporary Literature: The Moral Dilemma and the Reemergence of the East-West Debate…………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Chapter 5: Restoring Traditional Russia through Post-Soviet Film: Nostalgia, Reconciliation, and the Quest -

Formal Indication, Philosophy, and Theology: Bonhoeffer's Critique of Heidegger

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1-2007 Formal Indication, Philosophy, and Theology: Bonhoeffer's Critique of Heidegger Brian Gregor Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Gregor, Brian (2007) "Formal Indication, Philosophy, and Theology: Bonhoeffer's Critique of Heidegger," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 24 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil200724227 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol24/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. FORMAL INDICATION, PHILOSOPHY, AND THEOLOGY: BONHOEFFER’S CRITIQUE OF HEIDEGGER Brian Gregor This paper examines Heidegger’s account of the proper relation between philosophy and theology, and Dietrich Bonhoeff er’s critique thereof. Part I outlines Heidegger’s proposal for this relationship in his lecture “Phe- nomenology and Theology,” where he suggests that philosophy might aid theology by means of ‘formal indication.’ In that context Heidegger never articulates what formal indication is, so Part II exposits this obscure notion by looking at its treatment in Heidegger’s early lecture courses, as well as its roots in Husserl. Part III presents Bonhoeff er’s theological response, which challenges Heidegger’s att empt to maintain a neutral ontology that remains unaff ected by both sin and faith. -

Heidegger, Being and Time

Heidegger's Being and Time 1 Karsten Harries Heidegger's Being and Time Seminar Notes Spring Semester 2014 Yale University Heidegger's Being and Time 2 Copyright Karsten Harries [email protected] Heidegger's Being and Time 3 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Ontology and Fundamental Ontology 16 3. Methodological Considerations 30 4. Being-in-the-World 43 5. The World 55 6. Who am I? 69 7. Understanding, Interpretation, Language 82 8. Care and Truth 96 9. The Entirety of Dasein 113 10. Conscience, Guilt, Resolve 128 11. Time and Subjectivity 145 12. History and the Hero 158 13. Conclusion 169 Heidegger's Being and Time 4 1. Introduction 1 In this seminar I shall be concerned with Heidegger's Being and Time. I shall refer to other works by Heidegger, but the discussion will center on Being and Time. In reading the book, some of you, especially those with a reading knowledge of German, may find the lectures of the twenties helpful, which have appeared now as volumes of the Gesamtausgabe. Many of these have by now been translated. I am thinking especially of GA 17 Einführung in die phänomenologische Forschung (1923/24); Introduction to Phenomenological Research, trans. Daniel O. Dahlstrom (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2005) GA 20 Prolegomena zur Geschichte des Zeitbegriffs (1925); History of the Concept of Time, trans. Theodore Kisiel (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1985) GA 21 Logik. Die Frage nach der Wahrheit (1925/26). Logic: The Question of Truth, trans. Thomas Sheehan GA 24 Die Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie (1927); The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, trans. -

Marina Tsvetaeva 1

Marina Tsvetaeva 1 Marina Tsvetaeva Marina Tsvetaeva Tsvetaeva in 1925 Born Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva 8 October 1892 Moscow, Russian Empire Died 31 August 1941 (aged 48) Yelabuga, USSR Occupation Poet and writer Nationality Russian Education Sorbonne, Paris Literary movement Russian Symbolism Spouse(s) Sergei "Seryozha" Yakovlevich Efron Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (Russian: Мари́на Ива́новна Цвета́ева; 8 October [O.S. 26 September] 1892 – 31 August 1941) was a Russian and Soviet poet. Her work is considered among some of the greatest in twentieth century Russian literature.[1] She lived through and wrote of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Moscow famine that followed it. In an attempt to save her daughter Irina from starvation, she placed her in a state orphanage in 1919, where she died of hunger. As an anti-Bolshevik supporter of Imperialism, Tsvetaeva was exiled in 1922, living with her family in increasing poverty in Paris, Berlin and Prague before returning to Moscow in 1939. Shunned and suspect, Tsvetaeva's isolation was compounded. Both her husband Sergey Efron and her daughter Ariadna Efron (Alya) were arrested for espionage in 1941; Alya served over eight years in prison and her husband was executed. Without means of support and in deep isolation, Tsvetaeva committed suicide in 1941. As a lyrical poet, her passion and daring linguistic experimentation mark her striking chronicler of her times and the depths of the human condition. Marina Tsvetaeva 2 Early years Marina Tsvetaeva was born in Moscow, her surname evokes association with flowers. Her father was Ivan Vladimirovich Tsvetaev, a professor of Fine Art at the University of Moscow,[1] who later founded the Alexander III Museum, which is now known as the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. -

Appendix the Interpretive Turn in Phenomenology: a Philosophical

Appendix The Interpretive Turn in Phenomenology: A Philosophical History* GARY BRENT MADISON1 McMaster University It is experience ... still mute which we are concerned with leading to the pure expression of its own meaning. [E]xperience is the experience of human finitude. 1 Phenomenology and the Overcoming of Metaphysics Richard Rorty has said of phenomenology that it is "a form of philosophizing whose utility continues to escape me/' and that "hermeneutic philosophy" is a "vague and unfruitful" notion.2 Remarks such as these should be of no surprisel coming as they do from someone who does not view philosophy as (as Hegel said) "serious business"-Le'l as a reasoned and principled search for the truth of things-but rather as a kind of "professional dilettantism" and whol accordinglYI sees no difference between philosophy and literary criticism. It is hard to imagine two philosophers (if that is the right term to apply to Rorty) standing in greater contrast than Richard Rorty and Edmund Husser!. Whereas in Rorty's neopragmatic view philosophy can be nothing more than a kind of "culture chat" and 1 inasmuch as it may have some relevance to actual practicel a criterionlessl unprincipled "kibitzing" and "muddling through/' Husserl defended phenomenology because he saw it as a means at last for making of philosophy a "rigorous science/' one moreover which would be of supreme theoretical-critical relevance to the life of humanity.3 One thing Husserl meant by his programmatic remarks on this subject in his 1911 Logos articlel "Philosophy as Rigorous Science/1'4 is that a properly • This paper is dedicated to the memory of Franz Vandenbuschel 5J.1 of the University of Louvain (Leuven)1 who forty-some years ago introduced me as a young graduate student to the phenomenology of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty and who was killed in a collision with a train in 1990. -

Satsang, a Contemporary Religion of Convergence

Satsang, a Contemporary Religion of Convergence Rajarshi Roy (SPR, a voluntary role in Satsang) B.E.(Mech), M.B.A.(Finance) Senior Member, Satsang UK Senior IT Consultant London Abstract: Purpose of this study is to identify the similarities in beliefs, traditions, and rituals of all the existing religions or religious practices of the world and explore the possibilities of religious convergence. The study found that although there are many similarities in the principles of the major religions in the world none of the old and existing religions offer religious convergence where a union of existing religions is possible. Satsang, a contemporary religion founded by Sree Sree Thakur Anukulchandra (1888-1969), a prominent philanthropist and one of the greatest philosophers of recent times, supports convergence. This paper explained the importance of initiation in the creed of a superior ideal in each of the major religions. It has also examined in detail about how people from any faith, race or religion can practice the principles of Satsang doctrine along with existing religious practices to accomplish the spiritual quests of individuals. Keywords: Convergence, Conversion, Initiation, Religion, Living Ideal Introduction The term ‘Religious Convergence’ signifies a religious platform where all the existing and old religious believers and practitioners can perform unique spiritual practices belong to each religious group, under one platform without diluting individual identities to fulfil individuals’ spiritual quest. In other word it can be defined as union of all religions in one platform. Similarities in Principles in Major Religions in the World When one looks at all the major world religions, it is evident that that they are more similar than dissimilar in terms of their spiritual quest, the path of discipleship and goal of achieving holiness. -

The Lyrical Subject As a Poet in the Works of M. Cvetaeva, B. Pasternak, and R.M

Studi Slavistici x (2013): 129-148 Alessandro Achilli The Lyrical Subject as a Poet in the Works of M. Cvetaeva, B. Pasternak, and R.M. Rilke The human and poetic relationship between Marina Cvetaeva, Boris Pasternak and Rainer Maria Rilke has been one of the most challenging and fascinating issues of Slavic and comparative literature studies for several decades. Many books and essays have been written on the various aspects of this topic1, but it seems to be one of those inexhaustible themes on which scholars will continue to focus their attention for a long time to come. Before proceeding further, let us briefly recall some basic moments of their relation- ship. Reaching its peak in the Twenties, when the three writers exchanged letters and po- ems, their dialogue actually began in the previous decade. The symbolic significance of Pasternak’s first and only meeting with Rilke as a child, which he describes at the beginning of Oxrannaja gramota2, clearly hints at the fundamental meaning of the former’s readings of Mir zur Feier, Das Stunden-Buch and Das Buch von Bilder, and at the importance of their impact on the formation of Pasternak’s unique poetic manner in the years marked 1 The bibliography on this theme is very extensive. For the best, most recent and detailed account of Cvetaeva and Pasternak’s human and poetic relationship see Ciepiela 2006. For other contributions see Raevskaja-X’juz 1971, Taubman 1972, Ajzenštejn 2000 (a critical discussion of this monograph can be found in Gevorkjan 2012: 449-455), Baevskij 2004, El’nickaja 2000, Pasternak 2002, Thomson 1989, Taubman 1991, Shleyfer-Lavine 2011, Gasparov 1990, Polivanov 1992, Šmaina-Velikanova 2011, Nešumova 2006. -

1 Introduction Marina Tsvetaeva and Sophia Parnok Were Both Russian Poets Living During the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Introduction Marina Tsvetaeva and Sophia Parnok were both Russian poets living during the first half of the twentieth century. Tsvetaeva is considered one of the most prominent poets of the Silver Age, and is recognized for her innovative and complex style. Parnok is far less well-known, by Russians and scholars alike, and the process of re-establishing her as a figure in Russian literary history began just thirty years ago, with the work of scholars that will be discussed below. What connects these two women is the affair they conducted from 1914 to 1916, and the poetry they wrote chronicling it. This paper endeavors to examine the poetry of Tsvetaeva and Parnok in the context of that relationship, and also to consider how their poetry and thought on queerness evolved afterwards. The theme of Tsvetaeva and Parnok’s relationship, particularly from the perspective of what Tsvetaeva wrote in her Подруга [Girlfriend] cycle, has been treated in a number of studies to date. However, there are three main works which examine both this specific relationship in detail, and the queer sexualities of Tsvetaeva and Parnok throughout their entire lives. Sophia Polyakova is credited both with the re-discovery and rehabilitation of Parnok as a poet worth studying, and of being the first to publish work on the relationship between her and Tsvetaeva. Using poetic analysis and archival research, her book Незакатные оны дни: Цветаева и Парнок [Those Unfading Days: Tsvetaeva and Parnok] puts together a cohesive story about events within the relationship, considering both the experience of the two women as well as that of their social circle. -

March-April-En2018.Pdf

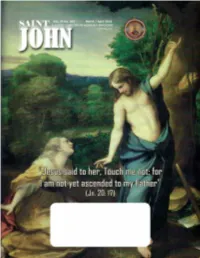

A ChristiAn CoptiC orthodox Bi-Monthly MAgAzine puBlished By “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 2:19). (ISSN # 1530-5600) In This Issue 21329 Cienega Ave. Schedule & News ......................................................................................................... 3 Covina، California 91724، Drills during Fasting ............................................. By Pope Shenouda 4 Fr. Youhanna Mouris our New Priest & Short Message .................................. 6 A parish of the Christian Coptic Orthodox Who Is This? (Palm Sunday) & the Magic Mustard Seed (Short Story) ......... 7 7 Words addressed to the Crucified ...................By Fr. Gawargios Kolta 8 Patriarchate of Egypt, and the diocese of Why & How we are Proud of the Cross? .... By Fr. Augustinos Hanna 10 Southern California. Reader’s Corner (A good night sleep) ..............By Mona Singh 12 St. John reflects the Biblical، doctrinal، and 6 Surprising times you are Quoting the Bible! .. Reader’s Digest 13 spiritual views of the early and modern Church He’s being a Christian ............................................By our servants in India 14 in English and Arabic. Faith and Righteousness .....................................By Dr. Emil Goubran 16 10 Commandments for Deacons / The Unique Christ By Mark Hanna 17 Editor in Chief: 10 Essential Works of the Blood of Christ .....By Fr. Augustinos 18 Fr. Augustinos Hanna Why do we Rejoice in Christ’s Resurrection ..... By Pope Shenouda 19 Congratulations & Condolences (God has a new Angel) ....... 20 New Face Book Page for St. John Church ...... By Fr. Youhanna Mauris 22 Design: Maged Graphics SCHEDULE of MEETINGS and EVENTS (909)702-9911 for the MONTH of September & October 2015 Customer Service: SUNDAY WEDNESDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY (626) 820-2739 + English Liturgy + Liturgy + Liturgy + Liturgy from 8-10 am 8:00 - 11:00 a.m. -

Platonov and the Soviet Natural World in the 1930S Carly Tozian Faculty Advisor

Tozian 1 Challenging Stalinist Exploitation: Platonov and the Soviet Natural World in the 1930s Carly Tozian Faculty Advisor: Professor James Goodwin Honors Thesis in Russian Studies 20 April 2021 Tozian 2 Introduction The 1920s and 1930s were not a time of literary liberty in the Soviet Union, nor were they a time for environmental protection. Under Stalin, the literary world and the natural world suffered similar prescriptions of exploitation. Stalin implemented policies such as the First Five Year Plan and the Belomor canal project which had detrimental effects upon the natural landscape. These plans were tailored for political and economic gain, no matter the cost of human or other life. In the literary sphere, writers were published only if they agreed to represent the progression of society into the ideal socialist world by adhering to the genre of Socialist Realism. For this reason, many works from well-known writers remained unpublished from the beginning of the1930s until Stalin’s death in 1953, chief among them, Andrei Platonov. Those of his works that were not published in his lifetime include The Foundation Pit, his short novel “The Juvenile Sea,” as well as other film scripts and plays. His novella “For Future Use” was published, but immediately received harsh criticism from other writers and even from Stalin (Pit 156-7). Through his unique style, Platonov “documented” the experiences he witnessed during the time of the First Five Year plan and the implementation of other Stalinist policies throughout his fictional works. I argue that Platonov fashions his own “real” socialist realist method in contrast to the prescribed one, which was committed to the party line. -

Peter Weiss. Andrei Platonov. Ragnvald Blix. Georg Henrik Von Wright. Adam Michnik

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. March 2011. Vol IV:1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Södertörn University, Stockholm FEATURE. Steklov – Russian BALTIC temple of pure thought W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S COPING WITH TRANSITIONS PETER WEISS. ANDREI PLATONOV. RAGNVALD BLIX. GEORG HENRIK VON WRIGHT. ADAM MICHNIK. SLAVENKA DRAKULIĆ. Sixty pages BETRAYED GDR REVOLUTION? / EVERYDAY BELARUS / WAVE OF RELIGION IN ALBANIA / RUSSIAN FINANCIAL MARKETS 2short takes Memory and manipulation. Transliteration. Is anyone’s suffering more important than anyone else’s? Art and science – and then some “IF YOU WANT TO START a war, call me. Transliteration is both art and science CH I know all about how it's done”, says – and, in many cases, politics. Whether MÄ author Slavenka Drakulić with a touch царь should be written as tsar, tzar, ANNA of gallows humor during “Memory and czar, or csar may not be a particu- : H Manipulation: Religion as Politics in the larly sensitive political matter today, HOTO Balkans”, a symposium held in Lund, but the question of the transliteration P Sweden, on December 2, 2010. of the name of the current president This issue of the journal includes a of Belarus is exceedingly delicate. contribution from Drakulić (pp. 55–57) First, and perhaps most important: in which she claims that top-down gov- which name? Both the Belarusian ernance, which started the war, is also Аляксандр Лукашэнка, and the Rus- the path to reconciliation in the region. sian Александр Лукашенко are in use. Balkan experts attending the sympo- (And, while we’re at it, should that be sium agree that the war was directed Belarusian, or Belarussian, or Belaru- from the top, and that “top-down” is san, or Byelorussian, or Belorussian?) the key to understanding how the war BW does not want to take a stand on began in the region.