William Mctaggart, RSA, VPRSW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 04-11

Newsletter No 36 Spring 2011 From the Chair Errata Many thanks to all those members who made it along Unfortunately due to an oversight some errors to our re-scheduled AGM (thanks to the snow) – it appeared in Louise Boreham’s essay in the last was great to see such a good turnout and thanks are Journal. The corrections are as follows: due to Simon Green for a fascinating talk and to the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland for letting 1. page 49, line 10 of paragraph 2, the name should us use the magnificent Glasite Meeting Room. be Blyth, with no 'e' on the end. I would also like to thank all of you who have so generously answered our plea for support for the 2. page 53, no 6, should have a closing bracket after journal – it’s really heartening to know that so many Fig.5 of you value the journal and were willing to help us meet its rising production costs. We still have a long 3. page 53, no 7a, the dates should read 1898 – 1934 way to go in order to put the journal on a sustainable footing, however, so if there are still any members Apologies for these mistakes. who were thinking about making a contribution, do please get in touch! Last year sadly saw quite a dip in our Notices membership numbers as the recession really started to bite. Our priority therefore has to be to get our Helen Adelaide Lamb, Illuminated numbers back up again, and once again we’d be very Manuscripts – Request for information grateful for anything you can do to help – if you By Helen E Beale know anyone who you think might be interested in joining, start badgering them now! Further information would be warmly welcomed on Finally, we will soon be advertising some the Illuminated Manuscripts of Helen Adelaide Lamb, guided tours and other events for members, so keep 1893-1981, a native of Dunblane, admitted to the an eye out for those, and we hope you’ll be able to Glasgow School of Art at the unusually young age of come along. -

Scottish Auction 2021

Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Helping landowners and Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May rural businesses www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Dinner Contents Your Scottish Auction dinner can be ordered and Chairman’s Welcome 3 delivered to your door UK wide (see pages 9 & 10). Executive Chairman Scotland’s Welcome 5 Timetable Acknowledgements 7 The 2021 Scottish Auction will run online, with a Dinner Arrangements 9 catalogue full of generous contributions from many varied supporters, and this year we are lucky enough to be Scottish Auction Committee 11 including several auction lots contributed from our GWCT committees in England. GWCT Events Calendar 13 The important dates are: How to Bid 14 23 April Place your orders for dinner and wine Saffery Champness specialise in accountancy, tax and business advisory services to onward www.gwct.org.uk/dinnerbox see page 9 for details Shooting 15 farms and estates across Scotland. We are here to help you and your business through Fishing 23 30 April, Bidding opens online at www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk these difficult times. 6pm Stalking 36 5 May Orders close for cases of wine Contact us or visit www.saffery.com to find out how we can support you. Art & Jewellery 46 9 May Dinner orders close midnight Something for Everyone 52 Max Floydd, Edinburgh Susie Swift, Inverness 12/13 May Dinner and wines delivered Food & Drink 63 T: +44 (0)131 221 2777 T: +44 (0)1463 246300 13 May Watch a short video from GWCT Scotland from 6.30pm www.gwct.org.uk/scotland/auction/ E: [email protected] E: [email protected] How to Bid (more information) 72 Enjoy your own Scottish Auction dinner at home, relax and bid! Ts&Cs 73 10pm Bidding closes www.saffery.com Catalogue design by www.readingroomdesign.co.uk Scottish Auction 2021 2 Scottish Auction 2021 3 “Many of our supporters have themselves faced t gives me great pleasure to introduce this year’s GWCT a very difficult Chairman’s IScottish Auction catalogue. -

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture (450) Thu, 10th Dec 2015, Edinburgh Lot 62 Estimate: £1500 - £2000 + Fees § SIR WILLIAM MACTAGGART P.P.R.S.A., R.A., F.R.S.E., R.S.W. (SCOTTISH 1903-1981) THE BEECHES Signed, oil on board 18cm x 25.5cm (7in x 10in) Exhibited: Aitken Dott & Son, Sir William MacTaggart, Christmas Exhibition 1966, no.51 Note: Sir William MacTaggart is an artist of whom Edinburgh has long and rightly been proud. He was a central figure of the Edinburgh Group, a loose collective of critically and commercially successful artists which included his peers Anne Redpath, Sir William Gillies, William Crozier and Adam Bruce Thompson. Beyond this, MacTaggart also held many key roles within the city's artistic institutions. Born in Loanhead, Midlothian, he went on to study at the Edinburgh College of Art, later taking up a teaching post there, as well as serving as president of the Society of Scottish Artists between 1933-36, and ultimately as president of the Royal Scottish Academy in the years 1959-64. A towering figure in the Scottish art scene, his contribution was also recognised out with Scotland from early on in his career; he was a member of and exhibiter in the Royal Academy, and was knighted in 1962. MacTaggart came from artist stock, successfully proving his own merit and emerging from the long shadow cast by his grandfather, the popular and influential "Scottish Impressionist" William McTaggart. Aside from a looseness and airy freedom of brushwork, their work has little in common, though they both looked towards artistic developments in France when formulating the basis of their own personal style. -

William Mctaggart, RSA, VPRSW

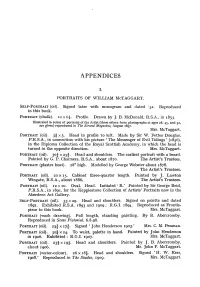

APPENDICES I. PORTRAITS OF WILLIAM McTAGGART. Self-Portrait (oil). Signed later with monogram and dated '52. Reproduced in this book. (chalk). Portrait iox6f. Profile. Drawn by J. B. McDonald, R.S.A., in 1853. Illustrated in series of portraits of the Artist (three others from photographs at ages 28, 45, and 52, are given) reproduced in The Strand Magazine, August 1897. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 3|x3. Head in profile to left. Made by Sir W. Fettes Douglas, P.R.S.A., in connection with his picture ' The Messenger of Evil Tidings ' (1856), in the Diploma Collection of the Royal Scottish Academy, in which the head is turned in the opposite direction. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 30^- x 25I. Head and shoulders. The earliest portrait with a beard. Painted by G. P. Chalmers, R.S.A., about 1870. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (plaster bust). 28" high. Modelled by George Webster about 1878. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 20 x 15. Cabinet three-quarter length. Painted by J. Lawton Wingate, R.S.A., about 1888. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 12x10. Oval. Head. Initialed ' R.' Painted by Sir George Reid, P.R.S.A., in 1891, for the Kepplestone Collection of Artists' Portraits now in the Aberdeen Art Gallery. Self-Portrait (oil). 33x29. Head and shoulders. Signed on palette and dated 1892. Exhibited R.S.A. 1893 and 1909 ; R.G.I. 1894. Reproduced as Frontis- piece to this book. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (wash drawing). Full length, standing painting. By R. Abercromby. Reproduced in Scots Pictorial, 6.8.98. -

Quaint Highlanders and the Mythic North: the Representation Of

Quaint Highlanders Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth Scotland’s myths and the cultural formations which carried centuries, the period covered here, Scotland underwent them are complex. great social, economic and cultural change. It was a time and the Mythic North: when painting came to be accorded tremendous significance, THE MYTH OF SCOTLAND both as a record of humanity’s highest achievements and as The term myth, in this context, is taken to mean a widely The Representation of a vehicle for the expression of elemental truths. In Britain accepted interpretative traditional story embodying in the nineteenth century the middle classes assigned great fundamental beliefs. Every country has its myths. They arise Scotland in Nineteenth significance to the art they bought in increasing quantities; via judicious appropriations from the popular history of the indeed, painting became their preferred instrument for country and function as a contemporary force endorsing the promotion of their vision of a prosperous modern belief or conduct in the present. They explain and interpret Century Painting society. Art was valued insofar as it expressed their highest the world as it is found, and both assert values and extol aspirations and deepest convictions, and it was a crucial identity. Here, in addition, the concept embodies something instrument in the task of moulding a society of people of the overtones of the moral teaching of a parable. who shared these values regardless of their class, gender or John Morrison wealth. If nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painting A myth is a highly selective memory of the past used to functioned to corroborate the narratives people used to stimulate collective purpose in the present. -

ANTHONY WOODD GALLERY 4 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6HZ 0131 558 9544/5 [email protected]

ANTHONY WOODD GALLERY 4 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6HZ 0131 558 9544/5 [email protected] www.anthonywoodd.com A BOOK LAUNCH OF JOSEPH HENDERSON RSW ‘DOYEN OF GLASGOW ARTISTS’ 1832-1908 By Hilary Christie-Johnston AND AN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS FROM THE HENDERSON FAMILY OF ARTISTS WILL RUN FROM 9 AUGUST – 9 SEPTEMBER 2013 Seascape by Joseph Henderson RSW (1832-1908) Joseph Henderson’s contribution to the burgeoning Glasgow art world in the second half of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th was profound. Glasgow became a centre of artistic activity in the 1860s, due in part to the establishment of the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts and the artists who formed the Glasgow Art Club of which Henderson was twice president. Opportunities reached a peak with the extravagant Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 with its six large galleries devoted to art. Then came the famous ‘Glasgow Boys’ who furthered the city’s reputation for art in the 1880s and 90s. Among the artists most regularly reviewed in The Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman was Joseph Henderson whose early works encompassed portraiture and genre painting but who later became renowned for his seascapes and extraordinary rendition of the west coast of Scotland. These feature prominently in this richly coloured illustrated book. And yet today, knowledge of his contribution requires renewal. Perhaps overshadowed by his son-in-law, the better known William McTaggart, and vying for recognition with his three artist sons, one of whom became Director of the Glasgow School of Art, few remember that Henderson had many paintings hung at the Royal Academy in London. -

Newsletter 08-10

Newsletter No 34 Summer 2010 From the Chair SSAH Grants As the economic crisis really starts to bite, the arts are Despite the recession, applications to our grants inevitably seen as an easy target. Within museums and scheme have actually tailed off notably of late, to the art galleries, the whole future of the profession is extent that we have not awarded any grants so far currently uncertain with the new UK government’s this year. Don’t forget that the society continues to recent announcement that the Museums, Libraries & offer research support grants from £50 to £300 to Archives Council is to be abolished, while in Scotland assist with research costs and travel expenses. the Museums Think Tank chaired by the Culture Applicants must be working at a post-graduate level Minister is taking a very critical look at the role of or above and should either be resident in Scotland or Museums Galleries Scotland and the way that the doing research that necessitates travel to Scotland. nationals and other museums in Scotland are funded. The society will accept applications quarterly Meanwhile almost every museum and gallery is having throughout the year, our aim being to handle to make cuts, while at the same time trying to demonstrate more clearly than ever before the value of submissions within three months of receipt. what they do to the widest possible audience. In this Recipients will be asked to write a report for the issue we cover just some of the many exciting newsletter, explaining how the grant was used. exhibitions coming up around Scotland in the next few Grants must be claimed within three months of the months – can I encourage you to show your support by award being made. -

Annual Review 2017–18 National Galleries of Scotland Annual Review

Annual Review 2017–18 national galleries of scotland annual review annual of scotland galleries national 2017–18 www.nationalgalleries.org froNt cover reverse Back cover reverse Facts and Figures visitor nuMBers NatioNal Galleries of s cotlaNd Board of t rustees Total visitors to National Galleries of 2,533,611 Benny Higgins Chairman Scotland sites in Edinburgh Tricia Bey Alistair Dodds 1,601,433 Scottish National Gallery Edward Green Lesley Knox 562,420 Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Tari Lang Catherine Muirden Professor Nicholas Pearce Scottish National Portrait Gallery 369,758 Willie Watt Nicky Wilson virtual v isitors seNior MaNaGeMeN t t eaM www.nationalgalleries.org website visits 1,989,101 Sir John Leighton Director-General educational v isits Chris Breward 33,210 Total number of participants from schools, Director of Collection and Research higher and further education Nicola Catterall Chief Operating Officer 19,479 Total number of adult participants at talks, Jo Coomber lectures and practical workshops Director of Public Engagement Jacqueline Ridge 4,333 Total number of community and Director of Conservation and Collections Management outreach participants Elaine Anderson 6,919 Total number of families with children at Head of Planning and Performance drop-in events fiNaNce friends Full Annual Accounts for 2017–18 are available on the National Galleries of Scotland website: 13,188 Friends at 31 March 2018 www.nationalgalleries.org volunteers froNt cover The Road Through the Rocks, Total number of volunteers Detail from Scottish National Gallery Scottish National Portrait Gallery Scottish National Gallery 166 Port-Vendres, 1926–27 by Charles of Modern Art One Rennie Mackintosh The Scottish National Gallery comprises The Scottish National Portrait Gallery is Back cover three linked buildings at the foot of the about the people of Scotland – past and Home to Scotland’s outstanding national The Road Through the Rocks, Port-Vendres, Mound in Edinburgh. -

Love, Loss and Landscape Published by Aberdeen University Press

JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 10, Issue 2 Love, Loss and Landscape Published by Aberdeen University Press in association with The Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies ISSN 1753-2396 Contents ‘James Lindsay – a late nineteenth-century Edinburgh art collector’ Per Kværne 1 James Joyce’s Labyrinths of Love and Desire in Exiles Saman Zoleikhaei 19 ‘The Quest through the Real’ Amir Barazande 49 ‘“It does not mak siccar you ken aboot weemin”: The Fight to be Heard in the Poetry of Joan Ure’ Richie McCaffery 56 ‘“An unbewildered poet”: The Ontological ‘Sense of Place’ in Seamus Heaney’s Prose’ Joanna Jarząb-Napierała 70 ‘On the move between shore and shore’: Scotland and Ireland’s history-makers, artists and the ‘Future State’ Craig Richardson 93 ‘“Out from Underneath Control” – A Conversation with David Greig’ Paula Sledzinska 114 List of Contributors 127 Editorial It was Joan Ure that captured something of the weight of the work examined here in writing, ‘This is a story that only seems sad at the end / but it is not sad because it is not a story but a /parable.’ Richie McCaffery quotes this passage in his excavation of Ure’s poetic enterprise, showing how she deployed verse to shape a space for her political and aesthetic ambitions as a writer. In this issue of the Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies we bring together a set of occasional papers that refl ect on the creative arts from the late nineteenth century to the contemporary scene. They have taken some time to gather together and I am grateful to the authors for their patience and kind responses to editorial queries. -

C.1986 GB584/WM Name of Creator: William Mctaggart RS

MIDLOTHIAN COUNCIL ARCHIVES WILLIAM MCTAGGART FAMILY COLLECTION c.1880 – c.1986 GB584/WM Name of Creator: William McTaggart RSA (1835-1910) and family Physical Description: 9 boxes or 12 square metres Biographical history: William McTaggart RSA (1835-1910) was one of the most celebrated Scottish painters of the late nineteenth century. He is regarded as one of the great interpreters of the Scottish landscape and is often described as the ‘Scottish Impressionist’. McTaggart was skilled in the use of both oil and watercolour, and in addition to Kintyre seascapes he also painted landscapes and seascapes in Midlothian and East Lothian. McTaggart was twice married: first to Mary Brochlan Holmes (1837-1884), with whom he had six children; and secondly to Marjory Henderson (1856-1936), with whom he had another nine children. William McTaggart lived at Dean Park house in Bonnyrigg between 1889 to his death on 2 April 1910. The collection also contains material specifically relating to his fifth daughter by his second marriage, Eliza or ‘Betty’ McTaggart (1896-1986). Betty became an accomplished artist in her own right and seems to have worked at Canongate nursery school, Edinburgh in the early 1950s. An article about Betty McTaggart’s sketchbooks of children at Cowgate nursery school appeared in the Edinburgh Evening News in January 2012. Several responses were received from former pupils at the nursery who are named in some of Betty McTaggart’s sketches. They confirmed that they attended the school in the early 1950s which suggests that Betty McTaggart worked there at that time. Scope and Content: The collection consists of 4 photograph albums and 51 photographs of William McTaggart RSA and his family, 3 miscellaneous photographs, and c.200 monochrome photographic reproductions of paintings by William McTaggart. -

Newsletter Contents 06-07

Newsletter No 26 Autumn/Winter 2007 From the Chair society, one which reflects our existing activities and membership but which we hope will appeal to a wider audience and help to attract many more people to ‘Art is long, and Time is fleeting.’ So Longfellow wrote join us. As part of this we have created new publicity and he knew a thing or two. Once again I must begin leaflets and will soon be redesigning the society’s by apologising for that fact that this issue has taken so website, but the most important factor in making all long to appear. Our plans for a new editor to take this work is our new logo. Our previous design, over the newsletter unfortunately failed to work out, though eye-catching at a certain size, has always been so I’m afraid what you’re reading here has had to be difficult to reproduce in the variety of ways that we somewhat hastily assembled by yours truly. It’s needed it to, and was looking increasingly out of place particularly frustrating as there have been some truly amid the cleaner, simpler logos of other organisations. inspiring exhibitions on over the summer which we Our first means of tackling this was a would have loved to feature while they were still on competition for art students, held earlier this year. show – my own favourite being the stunning Arts & This yielded some interesting ideas but none that was Crafts exhibition Hand, Heart & Soul at the City Art quite what we were looking for. In the end we Centre in Edinburgh. -

'Quite Unique in His Cemetery': Sir James Caw's Gravestone

‘Quite unique in his cemetery’: Sir James Caw’s gravestone Dennis Smith Sir James Lewis Caw (1864-1950) is a significant figure in Scottish art history, as a curator, critic and art historian. He was also, perhaps not coincidentally, married to the eldest daughter of the artist William McTaggart RSA (1835-1910) and a practising artist in his own right. After a spell as curator of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery he was appointed director of the National Gallery of Scotland (as it then was) in 1907 and remained in post till 1939, retiring at the age of 75. Both through his acquisitions for the Gallery and as art critic of The Scotsman for seventeen years he did much to shape artistic taste in Scotland. His book Scottish painting, past and present, 1620-1908 i provided the standard history of Scottish art for much of the 20th century. In the words of Duncan Macmillan, it ‘inspired and informed Scottish readers for over eighty years’ ii. Caw also produced monographs on Ramsay, Raeburn, Sir James Guthrie and – not least – his father-in-law William McTaggart. This article sets out to solve a minor puzzle about Sir James’s burial and to throw light on some of his family and artistic connections. Newington Cemetery in south Edinburgh was originally called Newington Necropolis but also features in old records as Echo Bank Cemetery or the Southern Cemetery. (A few elderly residents still talk of ‘Eckiebank’ but Echo Bank as a locality was effectively obliterated by the development of Prestonfield housing estate. Perhaps Prestonfield has a more prestigious ring.) The cemetery was established as a commercial venture in 1846 and subsequently laid out by the architect David Cousin (1809-1878).