David Scruton Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

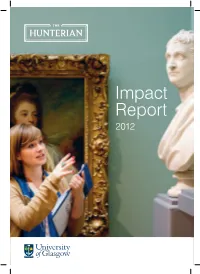

Hunterian Impact Report 2012

Impact Report 2012 Introduction 2012 has been a year of quite considerable The pace of this programme of activity and achievement for The Hunterian in terms of its academic development is relentless but hugely rewarding. and public engagement. Amongst our triumphs we Perhaps most significantly, our University has should mention the renewal and expanded hang recognised The Hunterian as being not only core of the Hunterian Art Gallery and the opening of our business in respect of its contribution to the University’s special exhibition Rembrandt and the Passion, both lead objectives for excellence in research, an to widespread critical acclaim; the publication of the excellent student experience and for helping to extend Antonine Wall Hunterian Treasures volume and of our institution’s global reach and reputation, but it Director’s Choice: The Hunterian; the strengthening of also points to the role of The Hunterian in our collections through a series of major new strengthening the University of Glasgow’s ability to acquisitions; the development of our international transform Scotland through its research, teaching, partnerships through collections exchange and joint outreach and cultural activities in the publication research activity; the launch of a new Hunterian brand University of Glasgow: Enriching Scotland. identity and significantly enhanced investment in Hunterian street presence; and the further expansion I would argue that the progress we have made in of our highly popular student engagement developing our strategy as a leading UK academic programme including the showcasing of the work of museum service, in the new campus-wide partnerships our first cohort of post-graduate Hunterian we have created, in our improved student offer and Associates, to name but a few. -

CHERRYBURN TIMES the Journal of the Bewick Society

Volume 5 Number 6 Summer 2009 CHERRYBURN TIMES The Journal of The Bewick Society Thomas Bewick in Scotland by Peter Quinn Alexander Nasmyth: Edinburgh seen from Calton Hill, 1825. Bewick visited Scotland on two occasions: 1776 and 1823. to a life spent mainly on Tyneside. However, these visits It is often assumed that the early visit gave Bewick a life-long introduce us to a world and set of concerns which Bewick enthusiasm for Scotland and all things Scottish and that in shared with Scots throughout his life, pre-dating even his first later years he made a sentimental journey northwards. Later great walk northwards. biographers have often thought the 1776 trip insignificant. In 1776 Bewick was 23 years old; in 1823 he arrived in David Croal Thomson, for instance: Edinburgh on his 70th birthday. He provides accounts of It is not necessary to follow Bewick in this excursion, which each trip in the Memoir: Chapter 6 dealing with 1776 was he details in his writings as the experience gained by it in an composed during his spell of writing confined at home with artistic way is inconsiderable. an attack of the gout: 29 May–24 June 1823. He visited Edin- Occurring at the beginning and end of Bewick’s career there burgh in August 1823, writing an account of the trip during is a temptation to simply contrast the two visits, emphasis- his last writing effort between 1824 and January 1827. ing the change that time, circumstance and fame had brought. We left Edinburgh on the 23rd of Augt 1823 & I think I shall The visits have been seen as two great Caledonian book ends see Scotland no more… ‘The Cadger’s Trot’: Thomas Bewick’s only lithograph, drawn on the stone in Edinburgh in 1823. -

Duncan Macmillan James Macpherson's Fragments of Ancient

Duncan Macmillan: Introduction 5 INTRODUCT I ON Duncan Macmillan James MacPherson’s Fragments of Ancient Poetry was published in 1760. Within the year, we learn from Howard Gaskill, it was translated into French by Diderot himself.1 In the two and a half centuries that have passed since then, the work has been translated into practically every literary language under the sun and it is likely that, somewhere, it has always been in print. That would be a remarkable bibliographic history for any book, but for a work whose exact nature was a matter of controversy from the day it was published and which has been routinely debunked as a fraud, it is truly extraordinary; nor does Ossian’s topicality seem to be fading even now in this post-modern era. On the contrary, the occasion for the conference whose transactions are recorded in this volume was the exhibition at the UNESCO building in Paris of Calum Colvin’s remarkable series of images, Ossian, Fragments of Ancient Poetry. It is a title which invokes MacPherson directly and the work itself is a striking witness to his enduring topicality. Among the essays below, the artist has contributed an illuminating commentary on his own work, backed by Tom Normand’s contribution which further examines it in the context of the photographic image and its role in the preservation, generation and perhaps even the creation of memory. Ossian, too, is in part at least a created memory. That analogy with an art form not invented till forty years after MacPherson’s death is typical of the way in which, for all that it is deliberately archaic, Ossian appears paradoxically also to be precociously modern. -

SIR DANIEL MACNEE. by the Eev. Walter C. Smith, D.D

24 August 1882, at the comparatively early age of sixty-four. He had been in failing health for about two years, but it was only a week before he died that he became seriously ill. His funeral took place in Warriston Cemetery on the 29th of August, and was attended by a large concourse of attached relatives and friends. Dr. Eobertson is survived by two sisters, with one of whom he resided, while the other is the wife of Mr. John Gillespie, "Writer to the Signet, and Secretary to the Eoyal Company of Archers. His youngest brother, Alexander, a promising artillery officer, was one of the many victims of the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Since the above was prepared, the writer has received a letter from one of Dr. Eobertson's medical compeers (Dr. George Bell) in reply to an application on the subject of his chess-playing, in which he says :—" Dr. Eobertson was no ordinary chess-player ; he understood the game, and practised it with judgment and skilL I know this, for the ' chequered field' was our favourite meeting-place during many years. Always pleasant there as elsewhere, Edinburgh does not know what a rare son she has lost. Though undemon- strative, the Eoyal Society had few such members as William Eobertson." SIR DANIEL MACNEE. By the Eev. Walter C. Smith, D.D. Daniel Macnee's life, like that of most hard workers, was not a very eventful one. Its chief incidents were its productions, and these were nowise startling, but rather such as might have been looked for—fruits of patient labour, and proofs of quiet growth. -

Directory for the City of Aberdeen

ABERDEEN CITY LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity185556uns mxUij €i% of ^krtimt \ 1855-56. TO WHICH tS AI)DEI< [THE NAMES OF THE PRINCIPAL INHABITAxnTs OLD ABERDEEN AND WOODSIDE. %httim : WILLIAM BENNETT, PRINTER, 42, Castle Street. 185 : <t A 2 8S. CONTENTS. PAGE. Kalendar for 1855-56 . 5 Agents.for Insurance Companies . 6 Section I.-- Municipal Institutions 9 Establishments 12 ,, II. — Commercial ,, III. — Revenue Department 24 . 42 ,, IV.—Legal Department Department ,, V.—Ecclesiastical 47 „ VI. — Educational Department . 49 „ VII.— Miscellaneous Registration of Births, Death?, and Marri 51 Billeting of Soldiers .... 51: The Northern Club .... Aberdeenshire Horticultural Society . Police Officers, &c Conveyances from Aberdeen Stamp Duties Aberdeen Shipping General Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of Aberd 1 Streets, Squares, Lanes, Courts, &c 124 Trades, Professions, &c 1.97 Cottages, Mansions, and Places in the Suburbs Append ix i Old Aberdeen x Woodside BANK HOLIDAYS. Prince Albert's Birthday, . Aug. 26 New Year's Day, Jan 1 | Friday, Prince of Birthday, Nov. 9 Good April 6 | Wales' Queen's Birthday, . Christmas Day, . Dec. 25 May 24 | Queen's Coronation, June 28 And the Sacramental Fasts. When a Holiday falls on a Sunday, the Monday following is leapt, AGENTS FOR INSURANCE COMPANIES. OFFICES. AGENTS Aberd. Mutual Assurance & Fiieudly Society Alexander Yeats, 47 Schoolhill Do Marine Insurance Association R. Connon, 58 Marischal Street Accidental Death Insurance Co.~~.~~., , A Masson, 4 Queen Street Insurance Age Co,^.^,^.^.—.^,.M, . Alex. Hunter, 61 St. Nicholas Street Agriculturist Cattle Insurance Co.-~,.,„..,,„ . A. -

189 Warriston Entry.Indd

City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh Survey of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 065 Warriston Cemetery (The Edinburgh Cemetery, Goldenacre) Consultants Peter McGowan Associates Landscape Architects and Heritage Management Consultants 6 Duncan Street Edinburgh EH9 1SZ 0131 662 1313 • [email protected] with Christopher Dingwall Research by Sonia Baker This report by Peter McGowan Survey visit: September 2007 Edinburgh Survey of Gardens 3 and Designed Landscapes 065 Warriston Cemetery (The Edinburgh Cemetery, Goldenacre) Parish Edinburgh NGR NT 253 757 Owner Public Cemetery: City of Edinburgh Council Designations Listing Cemetery, all monuments, catacombs, bridge, boundary walls, gates and gate piers: A Tree Preservation Order REASONS FOR INCLUSION The earliest of several 19th century ‘garden’ cemeteries that contribute to the urban form of the inner suburbs and to the amenity of the neighbouring streets, with significant values in terms of architectural features and memorials to prominent citizens. Dalry and Newington cemeteries are also included in the priority sites surveyed in 2007-08. The early 20th century extension and continued use makes Warriston different to the other sites. LOCATION, SETTING AND EXTENT Warriston is a large cemetery in three distinct parts occupying a tract of land north of the city centre and to the immediate north of the Water of Leith, west of Inverleith Row. Warriston Road, running from Canonmills to Ferry Road, forms much of the bending southern and eastern boundaries of the cemetery, with the Goldenacre Path cycleway along a former railway forming the west boundary and Easter Warriston housing to the north. The three parts are: the central area from the original cemetery (generally wooded and fairly neglected), a small area of the original site south of the Warriston Path cycleway (wooded and almost totally abandoned) and the later northern extension (overall more open and fair condition). -

DD391 Papers of Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone and His Trustees

DD391 Papers of Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone and his trustees c.1852 - 1903 The fonds consists of correspondence and other papers generated by Alexander Macdonald, including letters from the artists that Macdonald patronised. The trustees' papers include minutes, accounts, vouchers and correspondence detailing their administration of Macdonald's estate from 1884 until the division of the estate among the residuary legatees in 1902. The bundles listed by the National Register of Archives (Scotland) have not been altered since their deposit in the City Archives. During listing of the remaining papers, any other original bundles have been preserved intact. Bundles aggregated by the archivist during listing are indicated in the list with an asterisk. (15 boxes and one volume) DD391/1 Macdonald of Kepplestone: trust disposition, inventory, executry and subsidiary legal papers (1861, 1882-1885) 18611882 - 1885 DD391/1/1: Trust disposition and deed of settlement (1885); DD391/1/2: Copy trust disposition and settlement (1882) DD391/1/3: Draft abstract deed of settlement (1884); DD391/1/4: Inventories of estate (1885); DD391/1/5: Confirmation of executors (1885); DD391/1/6: Copy contract of marriage between Alexander Macdonald and Miss Hope Gordon (3 June 1861). (9 items) DD391/1/1 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: Trust disposition and deed of settlement, 11 December 1882, 1885 1882 - 1885 *Trust disposition and deed of settlement of Alexander Macdonald dated 11 December 1882. Printed at the Aberdeen Journal Office, 1885 (1 bundle, 14 copies) DD391/1/2 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: copy trust disposition and settlement, 11 December 1882 11 December 1882 *Copy trust disposition and settlement of Alexander Macdonald, and two draft trust dispositions and deed of settlements, 11 December 1882 (1 bundle, 3 items) DD391/1/3 Alexander Macdonald of Kepplestone: draft abstract deed of settlement, 11 December 1882 11 December 1882 *Draft abstract deed of settlement of Alexander Macdonald dated 11 December 1882. -

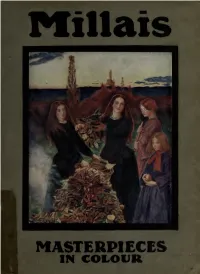

Masterpieces in Colour in M^Moma

Millais -'^ Mi m' 'fS?*? MASTERPIECES IN COLOUR IN M^MOMA FOR MA>4Y YEARS ATEACKEi;. IN THIS COLLEOE:>r55N.£>? THIS B(2);ClSONE^ANUMB€R FFPH THE LIBRARY 9^JvLK >10JMES PRESENTED TOTKEQMTARIO CDltECE 9^ART DY HIS REIATIVES D^'-CXo'.. MASTERPIECES IN COLOUR EDITED BY - - T. LEMAN HARE MILLAIS 1829--1S96 "Masterpieces in Colour" Series Artist. Author. BELLINI. Georgb Hay. BOTTICELLI. Henry B. Binns. BOUCHER. C. Haldane MacFall. burne.jones. A. Ly3 Baldry. carlo dolci. George Hay. CHARDIN. Paul G. Konody. constable. C. Lewis Hind. COROT. Sidney Allnutt. DA VINCL M. W. B ROCKWELL. DELACROIX. Paul G. Konody. DtTRER. H. E. A. Furst. FRA ANGELICO. James Mason. FRA FILIPPO LIPPI. Paul G. Konody. FRAGONARD. C Haldane MacFall. FRANZ HALS. Edgcumbe Staley. GAINSBOROUGH Max Rothschild. GREUZE. Alys Eyre MackLi.j. HOGARTH. C. Lewis Hind. HOLBEIN. S. L. Bensusan. HOLMAN HUNT. Mary E. Coleridge. INGRES. A. J. FiNBERG. LAWRENCE. S. L. Bensusan. LE BRUN, VIGEE. C. Haldane MacFail LEIGHTON. A. Lys Baldry, LUINL James Mason. MANTEGNA. Mrs. Arthur Bell. MEMLINC. W. H. J. & J. C. Wealb. MILLAIS. A. Lys Baldry. MILLET. Percy M. Turner. MURILLO. S. L. Bensusan. PERUGINO. Sblwyn Brinton. RAEBURN. James L. Caw. RAPHAEL. Paul G. Konody. REMBRANDT. JosEP Israels. REYNOLDS. S. L. Bensusan. ROMNEY. C. Lewis Hind. ROSSETTl LuciBN Pissarro. RUBENS. S. L. Bensusan. SARGENT. T. Martin Wood. TINTORETTO S. L. Bensusan. TITIAN. S. L. Bensusan. TURNER. C. Lewis Hind. VAN DYCK. Percy M. Turner. VELAZQUEZ. S. L. Bensusan. WATTEAU. C. Lewis Hinb. WATTS. W. LoFTUs Hark. WHISTLER. T. Martin Wood Others in Preparation. PLATE I.—THE ORDER OF RELEASE. -

Historic Memorials & Reminiscences of Stockbridge

Historic Memorials & Reminiscences of Stockbridge THE DEAN, AND WATER OF LEITH WITH NOTICES ANECDOTAL, DESCRIPTIVE, AND BIOGRAPHICAL. BY CUMBERLAND HILL, CHAPLAIN TO THE COMBINATION WORKHOUSE OF ST CUTHBERT's AND CANONGATE, EDINBURGH. ILLUSTRATED WITH SIX FULL-PAGE DRAWINGS. SECOND EDITION, ENLARGED. EDINBURGH: ROBERT SOMERVILLE, 10 SPRING GARDENS. RICHARD CAMERON, i ST DAVID STREET. 1887. <?W(fi1 5 ' •*- ' i i IC Lin TY university ui uullph PKEFACE TO THE FIEST EDITION. The substance of the following pages was delivered first as a lecture at the opening of the Working Men's Institute, Stockbridge, in March 1866. It was after- wards re-delivered, with additional notes, as two lectures, in Dean Street United Presbyterian Church, on the evenings of the 24th and 26th January 1871. At the close of the last lecture, I was requested to publish what I had delivered. Circumstances have prevented me from complying with this request until now. In the interval I have been enabled to add a good deal of curious matter connected with the locality that did not appear in any of the lectures. It will be remembered that I speak of the Stockbridge of the past more than of the present. In the course of the narrative I have mentioned the sources from whence the most material parts of my information have been derived. I may add that the subject is by no means exhausted. ;; IV ntEFACE. In most cases the source of my information has been acknowledged, but I have specially to mention the following works : —Ballantine's Life of David Roberts Cunningham's Lives of the British Painters. -

The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine

Études écossaises 16 | 2013 Ré-écrire l’Écosse : histoire A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland Peinture et parenté écossaises : l’influence transparente de l’école écossaise sur les tableaux irlandais d’Erskine Nicol Amélie Dochy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/837 DOI: 10.4000/etudesecossaises.837 ISSN: 1969-6337 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version Date of publication: 15 April 2013 Number of pages: 119-140 ISBN: 978-2-84310-246-2 ISSN: 1240-1439 Electronic reference Amélie Dochy, “A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland”, Études écossaises [Online], 16 | 2013, Online since 15 April 2014, connection on 15 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/837 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.837 © Études écossaises Amélie Dochy Université Toulouse 2 A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland “The Arts, unlike the exact sciences, are coloured by the temperaments, beliefs, and outward environment of the peoples amongst whom they flourish.” William D. mCKay, The Scottish School of Painting, 1906, p. 3. Erskine Nicol (3 July 1825–8 March 1904) was a Scottish painter who lived in Dublin between 1845 and 1850. When he went back to Scotland, his paintings attracted the attention of the British public for their fine quality, lively colours and the scenes taken from everyday life, so that by the 1850s, Nicol was already famous and was celebrated by art critics as the painter of Ireland. -

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (Nantes 1836- 1902 Doubs)

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com James Jacques Joseph Tissot (Nantes 1836- 1902 Doubs) Triumph of the Will – The Challenge Signed “J J Tissot” (lower right) Oil on canvas 85 x 43 in. (216 x 109 cm.) Painted circa 1877 Provenance The artist, until his death in 1902. Mlle Jeanne Tissot, until her death in 1964; her sale, Château de Buillon, 8-9 Nov 1964. Private collection, Besancon. Anonymous sale; Christie's Monaco, 15 June 1986, lot 119. Private collection. Anonymous sale; Sotheby’s, London, 9 June 1993, lot 25. Purchased by the previous owner in 1994. Exhibited London, Grosvenor Gallery, East Gallery, 1877, no. 22. Thos Agnew & Sons Ltd, registered in England No 00267436 at 21 Bunhill Row, London EC1Y 8LP VAT Registration No 911 4479 34 THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Literature: J. Ruskin, Fors Ciavigera Letter 79, E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), The Works of John Ruskin, Vol XXIX, p. 161. J. Laver, Vulgar Society - The Romantic Career of James Tissot, 1936, pp. 37-8, 69. W. E. Misfeldt, James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bibliocritical Study, Ann Arbor, University Microfilms 1971, pp. 168-70. M. Wentworth, James Tissot, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1984, pp. 136-8, 140, 141, 202. K. Matyjaskiewicz (Ed.), James Tissot (Catalogue to Exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, 1984-5), 1984, p. 115, no. 85. C. Wood, Tissot, 1986, p.