Love, Loss and Landscape Published by Aberdeen University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OT Introduction.Qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 1

OT Introduction.qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE OLD TESTAMENT BY William Henry Green OT Introduction.qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 3 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE OLD TESTAMENT THE CANON by William Henry Green D.D., LL.D LATE PROFESSOR OF ORIENTAL AND OLD TESTAMENT LITERATURE IN PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Quinta Press Weston Rhyn 2008 OT Introduction.qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 4 Quinta Press Meadow View, Weston Rhyn, Oswestry, Shropshire, England, SY10 7RN General Introduction to the Old Testament first published by Charles Scribner in 1898. First Quinta Press edition 2008 Set in 10pt on 12 pt Bembo Standard ISBN 1 897856 xx x OT Introduction.qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 5 BY THE SAME AUTHOR IN UNIFORM BINDING THE HIGHER CRITICISM OF THE PENTATEUCH. 8V0, $1.50 THE UNITY OF THE BOOK OF GENESIS. 8vo, $3.00 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE OLD TESTAMENT THE CANON BY WILLIAM HENRY GREEN, D.D., LL.D. PROFESSOR OF ORIENTAL AND OLD TESTAMENT LITERATURE IN PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1899 Copyright, 1898, by Charles Scribner’s Sons for the United States of America Printed by the Trow Directory Printing and Bookbinding Company, New York, USA. 5 OT Introduction.qxp:OT Introduction.Quark 5 12 2008 01:26 Page 6 vii PREFACE ANY ONE who addresses himself to the study of the Old Testament will desire first to know something of its character. It comes to us as a collection of books which have been and still are esteemed peculiarly sacred. -

Trajectory of Art of Exile from Joyce's Ulysses to Beckett's

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 35.1 March 2009: 205-228 Exile, Cunning, Silence: Trajectory of Art of Exile from Joyce’s Ulysses to Beckett’s Trilogy Li-ling Tseng Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University, Taiwan Abstract Toward the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen proclaims his famous defensive formula for future (Irish) art: “silence, exile, and cunning” (247). Stephen’s resolution to exile himself from a forcible religious, nationalistic, and aesthetic identification initiated in Portrait is faithfully materialized by Stephen’s several attempts of literary creation in Ulysses. Forced to roam Dublin city on Bloomsday, the new hero Bloom is living his every moment in exile. Ulysses exemplifies Joyce’s (via Stephen’s) art of exile in featuring the two main male characters as ideologically exiled beings and in spelling out through their cunning characterization a (living and writing) style of exile. It is established that a father-son-like relationship exists between Joyce and Beckett. In spite of Beckett’s protest against critics’ comparing him to Joyce, the route of exile initiated by Stephen on Joyce’s behalf is decisively taken up again and developed thoroughly in Beckett’s major oeuvres, The Trilogy. While the act of exile involves more the physical distancing from the socio-political Dublin city setting as maneuvered by Stephen and Bloom in Ulysses, Beckett’s Trilogy carries out a thoroughgoing exile or abstraction from a specific geopolitical setting, be it a city (i.e. Dublin) or a country (i.e. Ireland). My paper aims at examining Beckett’s diverse interaction with and influence under this Stephen-Joyce legacy in each of his Trilogy stories, primarily focusing on how Stephen’s formula has been experimented to be de-politicized and re-politicized in Beckett’s three works. -

The Performance of Joyce: Stage Directions in Dubliners, Exiles

The Performance of Joyce: Stage Directions in Dubliners, Exiles, and “Circe” BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Lotte Murrath 6145752 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. David Pascoe Second Reader: Dr. Onno Kosters June 2021 Murrath 1 Abstract James Joyce (1882-1941) was drawn to theatre and performance. He was particularly fascinated by the effect of stage directions, which he remediated from the play to different genres such as short stories and prose. This thesis investigates the way in which Joyce has been influenced by playwrights such as Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen, and how they contributed in shaping Joyce in, and outside of, his writing. The curious use of stage directions written in the past tense will be explored in “The Boarding House” and “The Dead”. Subsequently, the effect of sound and the construction of interior spaces on the experienced reliability of Joyce’s works will be charted. Additionally, the credibility of Joyce’s descriptions in the phantasmagoria of “Circe” will be examined. This will determine his proficiency in establishing the ultimate form of realism through the use of stage directions. Murrath 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Decisive Expressions .............................................................................................. -

SSHM Proceedings 1948-49

tcbe ~cotti~b ~ocietJ2 of tbe l)i~tor)2 of ~ebicine (Founded April, 1948.) REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS SESSION 1948.. 49. (!Cue .$cotttsb ,$ocictp of tbe JlistOiP of jRel:1icine. President Dr. DOUGLAS GUTHRIE. V iee-P l'esiden ts Mr W. 1. STUART. Profe3sor G. B. FLEMING (Glasgow) Hon. Secretary Dr. H. P. TAIT. Hon. TreaSUI'er Dr. W. A. ALEXANDER. Council Sir HENRY WADE. Dr. W. D. D. SMALL. Brig.-Gen. SUTTON. Professor CAMPBELL (Aberdeen). Dr. JOHN RITCHIE. Dr. HENRY GIBSON (Dundee). Dr. WILKIE MILLAR. Professor CHAS. M'NEIL. Mr A. L. GOODALL (Glasgow). The Senior President, Royal Medical Society. E ~bt 8tottisb ~otietp of tbe j!)istorp of ~ebicine. For many years it had been felt that there was a need for a Society in Scotland primarily devoted to the study of the History of Medicine and its allied Sciences. Such a Society came into being on 23rd April 1948, when a well attended and representative gathering of medical men and other interested persons from all over Scotland met in the Hall of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. It was then agreed to constitute the Society and to call it "The Scottish Society of the History of Medicine." A Constitution was drawn up and Office-Bearers for the ensuing year were elected. From this beginning the Society has grown steadily and now has a membership of some hundred persons. After the business of this Preliminary 1\1 eeting had been carried through, the Medical Superintendent of the Royal Infirmary of Dundee, Dr. Henry J. C. -

Newsletter 04-11

Newsletter No 36 Spring 2011 From the Chair Errata Many thanks to all those members who made it along Unfortunately due to an oversight some errors to our re-scheduled AGM (thanks to the snow) – it appeared in Louise Boreham’s essay in the last was great to see such a good turnout and thanks are Journal. The corrections are as follows: due to Simon Green for a fascinating talk and to the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland for letting 1. page 49, line 10 of paragraph 2, the name should us use the magnificent Glasite Meeting Room. be Blyth, with no 'e' on the end. I would also like to thank all of you who have so generously answered our plea for support for the 2. page 53, no 6, should have a closing bracket after journal – it’s really heartening to know that so many Fig.5 of you value the journal and were willing to help us meet its rising production costs. We still have a long 3. page 53, no 7a, the dates should read 1898 – 1934 way to go in order to put the journal on a sustainable footing, however, so if there are still any members Apologies for these mistakes. who were thinking about making a contribution, do please get in touch! Last year sadly saw quite a dip in our Notices membership numbers as the recession really started to bite. Our priority therefore has to be to get our Helen Adelaide Lamb, Illuminated numbers back up again, and once again we’d be very Manuscripts – Request for information grateful for anything you can do to help – if you By Helen E Beale know anyone who you think might be interested in joining, start badgering them now! Further information would be warmly welcomed on Finally, we will soon be advertising some the Illuminated Manuscripts of Helen Adelaide Lamb, guided tours and other events for members, so keep 1893-1981, a native of Dunblane, admitted to the an eye out for those, and we hope you’ll be able to Glasgow School of Art at the unusually young age of come along. -

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Scottish Auction 2021

Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Helping landowners and Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May rural businesses www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Dinner Contents Your Scottish Auction dinner can be ordered and Chairman’s Welcome 3 delivered to your door UK wide (see pages 9 & 10). Executive Chairman Scotland’s Welcome 5 Timetable Acknowledgements 7 The 2021 Scottish Auction will run online, with a Dinner Arrangements 9 catalogue full of generous contributions from many varied supporters, and this year we are lucky enough to be Scottish Auction Committee 11 including several auction lots contributed from our GWCT committees in England. GWCT Events Calendar 13 The important dates are: How to Bid 14 23 April Place your orders for dinner and wine Saffery Champness specialise in accountancy, tax and business advisory services to onward www.gwct.org.uk/dinnerbox see page 9 for details Shooting 15 farms and estates across Scotland. We are here to help you and your business through Fishing 23 30 April, Bidding opens online at www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk these difficult times. 6pm Stalking 36 5 May Orders close for cases of wine Contact us or visit www.saffery.com to find out how we can support you. Art & Jewellery 46 9 May Dinner orders close midnight Something for Everyone 52 Max Floydd, Edinburgh Susie Swift, Inverness 12/13 May Dinner and wines delivered Food & Drink 63 T: +44 (0)131 221 2777 T: +44 (0)1463 246300 13 May Watch a short video from GWCT Scotland from 6.30pm www.gwct.org.uk/scotland/auction/ E: [email protected] E: [email protected] How to Bid (more information) 72 Enjoy your own Scottish Auction dinner at home, relax and bid! Ts&Cs 73 10pm Bidding closes www.saffery.com Catalogue design by www.readingroomdesign.co.uk Scottish Auction 2021 2 Scottish Auction 2021 3 “Many of our supporters have themselves faced t gives me great pleasure to introduce this year’s GWCT a very difficult Chairman’s IScottish Auction catalogue. -

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture (450) Thu, 10th Dec 2015, Edinburgh Lot 62 Estimate: £1500 - £2000 + Fees § SIR WILLIAM MACTAGGART P.P.R.S.A., R.A., F.R.S.E., R.S.W. (SCOTTISH 1903-1981) THE BEECHES Signed, oil on board 18cm x 25.5cm (7in x 10in) Exhibited: Aitken Dott & Son, Sir William MacTaggart, Christmas Exhibition 1966, no.51 Note: Sir William MacTaggart is an artist of whom Edinburgh has long and rightly been proud. He was a central figure of the Edinburgh Group, a loose collective of critically and commercially successful artists which included his peers Anne Redpath, Sir William Gillies, William Crozier and Adam Bruce Thompson. Beyond this, MacTaggart also held many key roles within the city's artistic institutions. Born in Loanhead, Midlothian, he went on to study at the Edinburgh College of Art, later taking up a teaching post there, as well as serving as president of the Society of Scottish Artists between 1933-36, and ultimately as president of the Royal Scottish Academy in the years 1959-64. A towering figure in the Scottish art scene, his contribution was also recognised out with Scotland from early on in his career; he was a member of and exhibiter in the Royal Academy, and was knighted in 1962. MacTaggart came from artist stock, successfully proving his own merit and emerging from the long shadow cast by his grandfather, the popular and influential "Scottish Impressionist" William McTaggart. Aside from a looseness and airy freedom of brushwork, their work has little in common, though they both looked towards artistic developments in France when formulating the basis of their own personal style. -

William Mctaggart, RSA, VPRSW

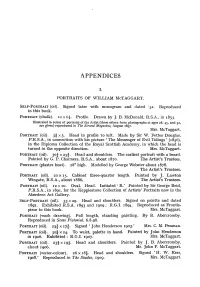

APPENDICES I. PORTRAITS OF WILLIAM McTAGGART. Self-Portrait (oil). Signed later with monogram and dated '52. Reproduced in this book. (chalk). Portrait iox6f. Profile. Drawn by J. B. McDonald, R.S.A., in 1853. Illustrated in series of portraits of the Artist (three others from photographs at ages 28, 45, and 52, are given) reproduced in The Strand Magazine, August 1897. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 3|x3. Head in profile to left. Made by Sir W. Fettes Douglas, P.R.S.A., in connection with his picture ' The Messenger of Evil Tidings ' (1856), in the Diploma Collection of the Royal Scottish Academy, in which the head is turned in the opposite direction. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 30^- x 25I. Head and shoulders. The earliest portrait with a beard. Painted by G. P. Chalmers, R.S.A., about 1870. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (plaster bust). 28" high. Modelled by George Webster about 1878. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 20 x 15. Cabinet three-quarter length. Painted by J. Lawton Wingate, R.S.A., about 1888. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 12x10. Oval. Head. Initialed ' R.' Painted by Sir George Reid, P.R.S.A., in 1891, for the Kepplestone Collection of Artists' Portraits now in the Aberdeen Art Gallery. Self-Portrait (oil). 33x29. Head and shoulders. Signed on palette and dated 1892. Exhibited R.S.A. 1893 and 1909 ; R.G.I. 1894. Reproduced as Frontis- piece to this book. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (wash drawing). Full length, standing painting. By R. Abercromby. Reproduced in Scots Pictorial, 6.8.98. -

189 Warriston Entry.Indd

City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh Survey of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 065 Warriston Cemetery (The Edinburgh Cemetery, Goldenacre) Consultants Peter McGowan Associates Landscape Architects and Heritage Management Consultants 6 Duncan Street Edinburgh EH9 1SZ 0131 662 1313 • [email protected] with Christopher Dingwall Research by Sonia Baker This report by Peter McGowan Survey visit: September 2007 Edinburgh Survey of Gardens 3 and Designed Landscapes 065 Warriston Cemetery (The Edinburgh Cemetery, Goldenacre) Parish Edinburgh NGR NT 253 757 Owner Public Cemetery: City of Edinburgh Council Designations Listing Cemetery, all monuments, catacombs, bridge, boundary walls, gates and gate piers: A Tree Preservation Order REASONS FOR INCLUSION The earliest of several 19th century ‘garden’ cemeteries that contribute to the urban form of the inner suburbs and to the amenity of the neighbouring streets, with significant values in terms of architectural features and memorials to prominent citizens. Dalry and Newington cemeteries are also included in the priority sites surveyed in 2007-08. The early 20th century extension and continued use makes Warriston different to the other sites. LOCATION, SETTING AND EXTENT Warriston is a large cemetery in three distinct parts occupying a tract of land north of the city centre and to the immediate north of the Water of Leith, west of Inverleith Row. Warriston Road, running from Canonmills to Ferry Road, forms much of the bending southern and eastern boundaries of the cemetery, with the Goldenacre Path cycleway along a former railway forming the west boundary and Easter Warriston housing to the north. The three parts are: the central area from the original cemetery (generally wooded and fairly neglected), a small area of the original site south of the Warriston Path cycleway (wooded and almost totally abandoned) and the later northern extension (overall more open and fair condition). -

SSAH Will Continue to Grow and Develop Its Role As One of the Pre-Eminent Vehicles of Art from the Chair Historical Research in Scotland

Newsletter No. 21 Autumn/Winter 2005 During that time the SSAH will continue to grow and develop its role as one of the pre-eminent vehicles of art From the Chair historical research in Scotland. Our 2005 Journal is a particularly rich and varied publication and we are now st lthough not exactly a ‘coming of age’, the 21 exploring opportunities for more extensive distribution birthday of the SSAH has offered a marvellous and online publishing. More news of this will follow. We opportunity to review both our past and our are delighted to have contributions from several scholars A st future. Our past was essentially the theme of our 21 and writers working outwith Scotland and hope this is a anniversary colloquium in April - Art & Scotland: the last harbinger of a growing internationalism, both for our 21 years - but this was no exercise in self-indulgent Society, but also for the study and appreciation of Scottish congratulation or navel-gazing. Instead a succession of art and for the study of art in Scotland. stimulating papers and discussions served to emphasise how vibrant and energising the issue of art continues to Robin Nicholson be in a nation now mystifyingly re-branded as the ‘best small country in the world’. Certainly none can deny that Scotland always has punched above its weight and the colloquium was Notices launched with Duncan Macmillan’s challenging thesis that the international influence of Scots artists might be signifi- cantly more extensive than previously thought. Obliquely AGM this set a theme for the following day’s debates which The Annual General Meeting of the Scottish Society for constantly returned to questions of Scottish culture, Art History will take place on Saturday December 3rd in identity and outlook.