Quaint Highlanders and the Mythic North: the Representation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 04-11

Newsletter No 36 Spring 2011 From the Chair Errata Many thanks to all those members who made it along Unfortunately due to an oversight some errors to our re-scheduled AGM (thanks to the snow) – it appeared in Louise Boreham’s essay in the last was great to see such a good turnout and thanks are Journal. The corrections are as follows: due to Simon Green for a fascinating talk and to the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland for letting 1. page 49, line 10 of paragraph 2, the name should us use the magnificent Glasite Meeting Room. be Blyth, with no 'e' on the end. I would also like to thank all of you who have so generously answered our plea for support for the 2. page 53, no 6, should have a closing bracket after journal – it’s really heartening to know that so many Fig.5 of you value the journal and were willing to help us meet its rising production costs. We still have a long 3. page 53, no 7a, the dates should read 1898 – 1934 way to go in order to put the journal on a sustainable footing, however, so if there are still any members Apologies for these mistakes. who were thinking about making a contribution, do please get in touch! Last year sadly saw quite a dip in our Notices membership numbers as the recession really started to bite. Our priority therefore has to be to get our Helen Adelaide Lamb, Illuminated numbers back up again, and once again we’d be very Manuscripts – Request for information grateful for anything you can do to help – if you By Helen E Beale know anyone who you think might be interested in joining, start badgering them now! Further information would be warmly welcomed on Finally, we will soon be advertising some the Illuminated Manuscripts of Helen Adelaide Lamb, guided tours and other events for members, so keep 1893-1981, a native of Dunblane, admitted to the an eye out for those, and we hope you’ll be able to Glasgow School of Art at the unusually young age of come along. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Platform for Success: Final Report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission

PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission © Crown copyright 2008 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5845-0 The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Broadcasting Commission by RR Donnelley B57086 Published by the Scottish Government, September, 2008 Further copies are available from Blackwell's Bookshop 53 South Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1YS Scottish Broadcasting Commission : 01 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 13 Chapter 2 Our Vision for Scottish Broadcasting 15 Chapter 3 Serving Audiences and Society 19 Chapter 4 A Network for Scotland 32 Chapter 5 Broadcasting and the Creative Economy 39 Chapter 6 Delivering the Future 51 Annex 56 02 : Scottish Broadcasting Commission FOREWORD In its short existence, the Scottish Broadcasting Commission has triggered a wide-ranging and frequently passionate debate about the future of the industry and the services it provides to audiences in Scotland. We intended from the beginning to make an impact which would lead to action, and there have been some encouraging early results in the form of new commitments from the broadcasters. But this is only a start. In publishing our final report and recommendations, we hope and expect that the debate will become even more visible and audible – with particular focus on the key opportunities and challenges we have identified in broadcasting and the new digital platforms. What has been refreshing is the extent to which both the industry and its audiences are at least as excited about the future as they are critical of some of the weaknesses of the past and present. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Migrating Minds

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 1 Migrating Minds AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 Autumn 2011 Migrating Minds Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Paul Shanks Associate Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal published twice yearly in autumn and spring by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. -

Scotland: BBC Weeks 51 and 52

BBC WEEKS 51 & 52, 18 - 31 December 2010 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office bbc.co.uk/pressoffice bbc.co.uk/iplayer THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEKS 51 & 52 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MONDAY 20 DECEMBER The Crash, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 21 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland WEDNESDAY 22 DECEMBER How to Make the Perfect Cake, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland THURSDAY 23 DECEMBER Pioneers, Prog 1/5 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Scotland on Song …with Barbara Dickson and Billy Connolly, NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 24 DECEMBER Christmas Celebration, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland Brian Taylor’s Christmas Lunch, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland A Christmas of Hope, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SATURDAY 25 DECEMBER Stark Talk Christmas Special with Fran Healy, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland On the Road with Amy MacDonald, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Stan Laurel’s Glasgow, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas Classics, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SUNDAY 26 DECEMBER The Pope in Scotland, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland MONDAY 27 DECEMBER Best of Gary:Tank Commander TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland The Hebridean Trail, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Two Scotland When Standing Stones, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Another Country Legends with Ricky Ross, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 28 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT -

Scottish Auction 2021

Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Helping landowners and Scottish Auction 2021 with additions UK-wide | online auction 30 April to 13 May rural businesses www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk Dinner Contents Your Scottish Auction dinner can be ordered and Chairman’s Welcome 3 delivered to your door UK wide (see pages 9 & 10). Executive Chairman Scotland’s Welcome 5 Timetable Acknowledgements 7 The 2021 Scottish Auction will run online, with a Dinner Arrangements 9 catalogue full of generous contributions from many varied supporters, and this year we are lucky enough to be Scottish Auction Committee 11 including several auction lots contributed from our GWCT committees in England. GWCT Events Calendar 13 The important dates are: How to Bid 14 23 April Place your orders for dinner and wine Saffery Champness specialise in accountancy, tax and business advisory services to onward www.gwct.org.uk/dinnerbox see page 9 for details Shooting 15 farms and estates across Scotland. We are here to help you and your business through Fishing 23 30 April, Bidding opens online at www.gwctscottishauction.co.uk these difficult times. 6pm Stalking 36 5 May Orders close for cases of wine Contact us or visit www.saffery.com to find out how we can support you. Art & Jewellery 46 9 May Dinner orders close midnight Something for Everyone 52 Max Floydd, Edinburgh Susie Swift, Inverness 12/13 May Dinner and wines delivered Food & Drink 63 T: +44 (0)131 221 2777 T: +44 (0)1463 246300 13 May Watch a short video from GWCT Scotland from 6.30pm www.gwct.org.uk/scotland/auction/ E: [email protected] E: [email protected] How to Bid (more information) 72 Enjoy your own Scottish Auction dinner at home, relax and bid! Ts&Cs 73 10pm Bidding closes www.saffery.com Catalogue design by www.readingroomdesign.co.uk Scottish Auction 2021 2 Scottish Auction 2021 3 “Many of our supporters have themselves faced t gives me great pleasure to introduce this year’s GWCT a very difficult Chairman’s IScottish Auction catalogue. -

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture (450) Thu, 10th Dec 2015, Edinburgh Lot 62 Estimate: £1500 - £2000 + Fees § SIR WILLIAM MACTAGGART P.P.R.S.A., R.A., F.R.S.E., R.S.W. (SCOTTISH 1903-1981) THE BEECHES Signed, oil on board 18cm x 25.5cm (7in x 10in) Exhibited: Aitken Dott & Son, Sir William MacTaggart, Christmas Exhibition 1966, no.51 Note: Sir William MacTaggart is an artist of whom Edinburgh has long and rightly been proud. He was a central figure of the Edinburgh Group, a loose collective of critically and commercially successful artists which included his peers Anne Redpath, Sir William Gillies, William Crozier and Adam Bruce Thompson. Beyond this, MacTaggart also held many key roles within the city's artistic institutions. Born in Loanhead, Midlothian, he went on to study at the Edinburgh College of Art, later taking up a teaching post there, as well as serving as president of the Society of Scottish Artists between 1933-36, and ultimately as president of the Royal Scottish Academy in the years 1959-64. A towering figure in the Scottish art scene, his contribution was also recognised out with Scotland from early on in his career; he was a member of and exhibiter in the Royal Academy, and was knighted in 1962. MacTaggart came from artist stock, successfully proving his own merit and emerging from the long shadow cast by his grandfather, the popular and influential "Scottish Impressionist" William McTaggart. Aside from a looseness and airy freedom of brushwork, their work has little in common, though they both looked towards artistic developments in France when formulating the basis of their own personal style. -

The Films of Murray Grigor for IOT

Atelier e.B + PAnel Present steel uPon the swArd the Films of Murray Grigor for IOT. II 9/10 & 30 MAy 12 rose street GlAsGow FilM theAtre Glasgow G3 6rB saturday 9 May: CumbernAuld hit & The demarCo diMension (edited by rob Kennedy) sunday 10 May: steel uPon the swArd & E.P. SculPtor saturday 30 May: Mackintosh T& he FAll And rise oF Mackintosh Murray Grigor is an independent Scottish filmmaker, writer and exhibition curator. Winning international acclaim for his ongoing contribution to the arts spanning over 40 years, The Inventors of Tradition II presents a series of three double bills in partnership with Glasgow Film Theatre that celebrate his work. The selected films highlight Grigor’s interest in Scottish artistic life and bring focus to the complex connections between architecture, creative practice and cultural identity prevalent in his pioneering works. steel uPon the swArd Saturday 9 May 2015 Saturday 30 May 2015 3pm PrOGrAMMe 3pm Cinema 2 Cinema 2 Sunday 10 May 2015 CuMBernAuld HIT (edited by Rob Kennedy) MACKIntosh 3pm Sponsored by Cumbernauld Development Corporation, Cinema 2 Mackintosh (1968), Murray Grigor’s first independent and Cumbernauld Hit (1977) is an original take on ‘promotional’ seminal film won five international awards, helping to re- films produced for Scotland’s New Towns during the STeel uPOn THe Sward establish the reputation of the architect and designer, now 1970s. Footage selected from Grigor’s original feature, by From the 1970s Grigor made art and architecture a celebrated world-wide as one of the most creative figures artist Rob Kennedy, creates a new work that is at once a focus of his filmmaking. -

William Mctaggart, RSA, VPRSW

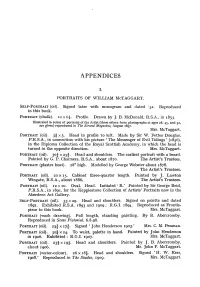

APPENDICES I. PORTRAITS OF WILLIAM McTAGGART. Self-Portrait (oil). Signed later with monogram and dated '52. Reproduced in this book. (chalk). Portrait iox6f. Profile. Drawn by J. B. McDonald, R.S.A., in 1853. Illustrated in series of portraits of the Artist (three others from photographs at ages 28, 45, and 52, are given) reproduced in The Strand Magazine, August 1897. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 3|x3. Head in profile to left. Made by Sir W. Fettes Douglas, P.R.S.A., in connection with his picture ' The Messenger of Evil Tidings ' (1856), in the Diploma Collection of the Royal Scottish Academy, in which the head is turned in the opposite direction. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (oil). 30^- x 25I. Head and shoulders. The earliest portrait with a beard. Painted by G. P. Chalmers, R.S.A., about 1870. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (plaster bust). 28" high. Modelled by George Webster about 1878. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 20 x 15. Cabinet three-quarter length. Painted by J. Lawton Wingate, R.S.A., about 1888. The Artist's Trustees. Portrait (oil). 12x10. Oval. Head. Initialed ' R.' Painted by Sir George Reid, P.R.S.A., in 1891, for the Kepplestone Collection of Artists' Portraits now in the Aberdeen Art Gallery. Self-Portrait (oil). 33x29. Head and shoulders. Signed on palette and dated 1892. Exhibited R.S.A. 1893 and 1909 ; R.G.I. 1894. Reproduced as Frontis- piece to this book. Mrs. McTaggart. Portrait (wash drawing). Full length, standing painting. By R. Abercromby. Reproduced in Scots Pictorial, 6.8.98. -

ANTHONY WOODD GALLERY 4 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6HZ 0131 558 9544/5 [email protected]

ANTHONY WOODD GALLERY 4 Dundas Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6HZ 0131 558 9544/5 [email protected] www.anthonywoodd.com A BOOK LAUNCH OF JOSEPH HENDERSON RSW ‘DOYEN OF GLASGOW ARTISTS’ 1832-1908 By Hilary Christie-Johnston AND AN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS FROM THE HENDERSON FAMILY OF ARTISTS WILL RUN FROM 9 AUGUST – 9 SEPTEMBER 2013 Seascape by Joseph Henderson RSW (1832-1908) Joseph Henderson’s contribution to the burgeoning Glasgow art world in the second half of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th was profound. Glasgow became a centre of artistic activity in the 1860s, due in part to the establishment of the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts and the artists who formed the Glasgow Art Club of which Henderson was twice president. Opportunities reached a peak with the extravagant Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 with its six large galleries devoted to art. Then came the famous ‘Glasgow Boys’ who furthered the city’s reputation for art in the 1880s and 90s. Among the artists most regularly reviewed in The Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman was Joseph Henderson whose early works encompassed portraiture and genre painting but who later became renowned for his seascapes and extraordinary rendition of the west coast of Scotland. These feature prominently in this richly coloured illustrated book. And yet today, knowledge of his contribution requires renewal. Perhaps overshadowed by his son-in-law, the better known William McTaggart, and vying for recognition with his three artist sons, one of whom became Director of the Glasgow School of Art, few remember that Henderson had many paintings hung at the Royal Academy in London. -

RICHARD MURPHY of Its Time and of Its Place « Blog

Home page Blog Libro Lithospedia blog Pietre d'Italia english version 22 maggio 2013 News RICHARD MURPHY Of its time and of its place RICHARD MURPHY Of its time and of its place Lectio Magistralis Giovedì 30 maggio 2013 alle ore 21.00 Museo di Castelvecchio di Verona Sala Boggian Giovedì 30 maggio 2013 alle ore 21.00, presso il Museo di Castelvecchio di Verona, Sala Boggian, si terrà la Lectio Magistralis dell’architetto scozzese Richard Murphy dal titolo OF ITS TIME AND OF ITS PLACE L’evento è organizzato da Veronafiere nell’ambito delle attività culturali della 48° Marmomacc in collaborazione con il Comune di Verona, Direzione Musei d’Arte e Monumenti e l’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori della Provincia di Verona. Appassionato conoscitore della grande tradizione architettonica inglese otto-novecentesca, Richard Murphy ha esteso il suo interesse all’opera di Carlo Scarpa. Lungo questo percorso ha costruito un legame fruttuoso con il Museo di Castelvecchio mediante una ricerca sull’opera del maestro veneziano, approfondendone pragmaticamente gli aspetti costruttivi e in particolare rilevando l’intervento nel castello scaligero. Contemporaneamente, la sua ventennale attività di architetto ha prodotto un interessante repertorio di lavori nei quali sono state indagate le relazioni tra luogo e storia, ed esplorate le potenzialità dei materiali con particolare sensibilità per l’uso della pietra. La Lectio Magistralis sarà preceduta dagli interventi di saluto del Comune di Verona, di Veronafiere, dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Verona, e introdotta da Alba Di Lieto della Direzione del Museo di Castelvecchio che parlerà del sodalizio culturale tra l’Istituzione veronese e l’architetto scozzese. -

The Films of Murray Grigor for IOT

Atelier e.B + PAnel Present steel uPon the swArd the Films of Murray Grigor for IOT. II 9/10 & 30 MAy 12 rose street GlAsGow FilM theAtre Glasgow G3 6rB saturday 9 May: CumbernAuld hit & The demarCo diMension (edited by rob Kennedy) sunday 10 May: steel uPon the swArd & E.P. SculPtor saturday 30 May: Mackintosh T& he FAll And rise oF Mackintosh Murray Grigor is an independent Scottish filmmaker, writer and exhibition curator. Winning international acclaim for his ongoing contribution to the arts spanning over 40 years, The Inventors of Tradition II presents a series of three double bills in partnership with Glasgow Film Theatre that celebrate his work. The selected films highlight Grigor’s interest in Scottish artistic life and bring focus to the complex connections between architecture, creative practice and cultural identity prevalent in his pioneering works. steel uPon the swArd Saturday 9 May 2015 Saturday 30 May 2015 3pm proGraMMe 3pm Cinema 2 Cinema 2 Sunday 10 May 2015 CuMbernauld HIT (edited by Rob Kennedy) MaCkInToSH 3pm Sponsored by Cumbernauld Development Corporation, Cinema 2 Mackintosh (1968), Murray Grigor’s first independent and Cumbernauld Hit (1977) is an original take on ‘promotional’ seminal film won five international awards, helping to re- films produced for Scotland’s New Towns during the STeel upon THe SWard establish the reputation of the architect and designer, now 1970s. Footage selected from Grigor’s original feature, by From the 1970s Grigor made art and architecture a celebrated world-wide as one of the most creative figures artist Rob Kennedy, creates a new work that is at once a focus of his filmmaking.