Explorations in the Icy North: How Travel Narratives Shaped Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir John Franklin and the Arctic

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING THE PROGRESS OF BRITISH ENTERPRISE FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINE~EENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN WINTER QUARTERS IN THE A.ROTIO REGIONS. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN. BY P. L. SIMMONDS, HONORARY AND CORRESPONDING JIIEl\lBER OF THE LITERARY AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF QUEBEC, NEW YORK, LOUISIANA, ETC, AND MANY YEARS EDITOR OF THE COLONIAL MAGAZINE, ETC, ETC, " :Miserable they Who here entangled in the gathering ice, Take their last look of the descending sun While full of death and fierce with tenfold frost, The long long night, incumbent o•er their heads, Falls horrible." Cowl'ER, LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & CO., SOHO SQUARE. MDCCCLI. TO CAPT. SIR W. E. PARRY, R.N., LL.D., F.R.S., &c. CAPT. SIR JAMES C. ROSS, R.N., D.C.L., F.R.S. CAPT. SIR GEORGE BACK, R.N., F.R.S. DR. SIR J. RICHARDSON, R.N., C.B., F.R.S. AND THE OTHER BRAVE ARCTIC NAVIGATORS AND TRAVELLERS WHOSE ARDUOUS EXPLORING SERVICES ARE HEREIN RECORDED, T H I S V O L U M E I S, IN ADMIRATION OF THEIR GALLANTRY, HF.ROIC ENDURANCE, A.ND PERSEVERANCE OVER OBSTACLES OF NO ORDINARY CHARACTER, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THEIR VERY OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère. -

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area's Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community

Historical Profile of the Great Slave Lake Area’s Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community by Gwynneth Jones Research and & Aboriginal Law and Statistics Division Strategic Policy Group The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice Canada. i Table of Contents Abstract ii Author’s Biography iii I. Executive Summary iv II. Methodology/Introduction vi III. Narrative A. First Contact at Great Slave Lake, 1715 - 1800 1 B. Mixed-Ancestry Families in the Great Slave Lake Region to 1800 12 C. Fur Trade Post Life at 1800 19 D. Development of the Fur Trade and the First Mixed-Ancestry Generation, 1800 - 1820 25 E. Merger of the Fur Trade Companies and Changes in the Great Slave Lake Population, 1820 - 1830 37 F. Fur Trade Monopoly and the Arrival of the Missionaries, 1830 - 1890 62 G. Treaty, Traders and Gold, 1890 - 1900 88 H. Increased Presence and Regulations by Persons not of Indian/ Inuit/Mixed-Ancestry Descent, 1905 - 1950 102 IV. Discussion/Summary 119 V. Suggestions for Future Research 129 VI. References VII. Appendices Appendix A: Extracts of Selected Entries in Oblate Birth, Marriage and Death Registers Appendix B: Métis Scrip -- ArchiviaNet (Summaries of Genealogical Information on Métis Scrip Applications) VIII. Key Documents and Document Index (bound separately) Abstract With the Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Powley [2003] 2 S.C.R., Métis were recognized as having an Aboriginal right to hunt for food as recognized under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

NOTE C8p. EDPS PRICE DESCRIPTORS

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 039 044 RC 004 271 TITLE Northwest Territories and Arctic Quebec. Education Review, 1465-66. INSTITUTIOm Canadian Dept. of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa (Ontario). PIT; DATE 66 NOTE c8p. EDPS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.90 HC-$3.°0 DESCRIPTORS *Administration, Adult Education, American Indians, *Annual Reports, Construction Programs, *Curriculum, *Education, Eskimos, Personnel, Placement, *Rural Areas, School Services, Special Programs, Statistical Data, Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS Arctic Quebec, Northwest Territories ABSTRACT Information on the educational growth of, and present operations for, students in the Northwest Territories and for Eskimo and Indian students in Arctic Quebec is presented in this annual review for 1965-1966. Administrativeconcerns of the school system are given, along with a look at curricular innovations. The vocational education program is reviewed, anda graph compares vocational training outside the Northwest Territories with that inside the territory. The adult educationprogram, school services, and construction programs are also discussed. Charts and tables provide supporting statistical data. (BD) Placation ewe/965-66 didArdweitwile 1;tritcktielue ec HONOURABLEMinister of IndianIssued ARTHUR Affairs under and theLAING, Northernauthority P.C., Developmentof M.P., B.S.A., 4 e . +IF A '4 ro U.S. DEPARTMENTOFFICE OF HEALTH, OF EDUCATION EDUCATION & WELFARE NorthernEDUCATION Administration DIVISION Branch Sir John Franklin School, Y ellowknife,N.W.T. PERSONTHISSTATED DOCUMENT -

Entente De Règlement Consolidé

N° du dossier de la Cour : T-2169-16 COUR FÉDÉRALE INSTANCE AUTORISÉE À TITRE DE RECOURS COLLECTIF ENTRE : GARRY LESLIE MCLEAN, ROGER AUGUSTINE, CLAUDETTE COMMANDA, ANGELA ELIZABETH SIMONE SAMPSON, MARGARET ANNE SWAN AND MARIETTE BUCKSHOT demandeurs et SA MAJESTÉ LA REINE DU CHEF DU CANADA, représentée par LE PROCUREUR GENERAL DU CANADA défenderesse ACCORD CONSOLIDÉ ATTENDU QUE : A. Le 31 juillet 2009, les demandeurs ont déposé un recours collectif putatif devant la Cour du Banc de la Reine du Manitoba portant le n° du dossier CI09-01-62181, McLean et al. c Procureur général du Canada. Le 24 novembre 2009, une déclaration amendée a été déposée. B. En mai 2016, les demandeurs ont retenu les services de l'avocat représentant le groupe. Le 17 novembre, ils ont déposé une nouvelle déclaration dans le recours devant la Cour du Banc de la Reine du Manitoba portant le n° de dossier CI09-01- 62181. Simultanément, le 15 décembre 2016, les demandeurs ont déposé une déclaration devant la Cour fédérale portant le n° de dossier de la Cour T-2169-16, McLean et al. c SMR. C. La procédure devant la Cour fédérale ainsi que la procédure devant la Cour du Banc de la Reine du Manitoba demandent une indemnité et d'autres avantages pour les slaves qui ont fréquenté les externats indiens fédéraux. D. A partir des années 1920, les étudiants autochtones de l'ensemble du Canada ont été tenus de fréquenter des écoles, y compris les externats indiens. Les externats indiens fédéraux étaient établis, financés, contrôlés et gérés par le Canada. -

The Metis Cultural Brokers and the Western Numbered Treaties, 1869-1877

The Metis Cultural Brokers and the Western Numbered Treaties, 1869-1877 A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Allyson Stevenson Copyright Allyson Stevenson, August 2004 . 1 rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Graduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection . I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work, or, in his absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done . It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission . It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis . Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to : Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Abstract i Throughout the history of the North West, Metis people frequently used their knowledge of European, Indian, and Metis culture to mediate Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal social, diplomatic, and economic encounters . -

The Great Bear Lake: Its Place in History

One of the chimneys of the old Fort Confidence as it was in 1964. The chimneys are all that remain of the fort which was constructed in 1836 and last occupied in 1852. The Great Bear Lake: Its Place in History LIONEL JOHNSON1 INTRODUCTION Great Bear Lake (Fig. 1) is one of the most prominent geographic features of northern Canada. Shaped likethe missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle, with five arms radiating from a central body, it has a total area of 31,150 square kilometres - approximately the same as that of the Netherlands. It is the eighth largest, and by far the most northerly, of the world's major lakes, and probably the least productive. (Johnson 1975a). PIG. 1 Great Bear Lake and surrounding area. The Arctic Circle transects the northernmost arm of the lake, and so the sun is visible from it for 24 hours a day in June, while in mid-winter daylight lasts for only twoto three hours. In July, the mean daily maximumtemperature is 19OC, in sharp contrast to the equivalent January figure of -27OC. Warm summers and cold winters, together with a total annual precipitation of about 230 millimetres, give rise to conditions which may best be described as northern continental. Up to two metres of ice form on the lake by April, when the snow on the 1Freshwater Institute, Environment Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. 232 GREAT BEAR LAKE surrounding land begins to melt; and it is not until middle of July, or even later in some years, that the waters become ice-free. -

Robert Campbell (1808-1894)

248 ARCTIC PROFILES Robert Campbell (1 808- 1894) Photo courtesy of Hudson’s Bay Company. ARCTIC PROFILES 249 Known as “Campbell of the Yukon,” a sobriquet that com- passion, his devout Christian faith, and his courage in the face memorates his yearsas an explorer and fur trader inthe of personal danger. Thosewho earned his ire, and there were a southern Yukon, Robert Campbellwas born in 1808 in Perth- number,discovered Campbell’s other side. His correspon- shire, Scotland. Stories told by his cousin, Chief Factor James dence reveals a dour, unforgiving man given to extreme and McMillan of the Hudson’s Bay Company, sparked an intense unreasonable criticism of Company officers he felt were not interest in the North American frontier. In 1830 at the age of assisting his efforts as an explorer with sufficient zeal. Camp- 22 he was hired to work on the Company’s experimental farm bell’s constant complaints, repeated threats to retire (all at Red River. The work provedless exciting than he expected, recanted), and his tendency to overrate his importance to the and after four years he requested a transfer to the fur trade. Hudson’s Bay Company angered many of his fellow officers. Campbell spent two unproductive years in the Dease Lake Robert Campbell dearly sought the fame he felt would ac- area, trying to break the Russian American Fur Company’s company geographic discoveries in the far North, buthe holdon the interior fur trade. An agreement betweenthe lacked the flair and originality of other northern explorers. H.B.C. and R.A.F.C. -

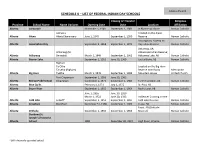

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2002

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2002 Geschichte: Allgemeines und Einführungen ........................................................................................................... 2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie.......................................................................................................... 2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein)........ 3 Historische Hilfswissenschaften.............................................................................................................................. 5 Ur- und Frühgeschichte; Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie ................................................................................ 8 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege ..................................... 12 Alte Geschichte ..................................................................................................................................................... 21 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit .............................................................................................. 22 Deutsche Geschichte ............................................................................................................................................. 25 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte..................................................................................................... 35 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, Ungarns, -

John Tod: “Career of a Scotch Boy.” Edited, with an Introduction and Notes, by Madge Wolfenden 133

THE BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY ccL JULY-OCTOBER, 1954 “çmj BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in co-operation with the British Columbia Historical Association. EDITOR Wju..iw E. IRELAND, Provincial Archives, Victoria. ASSOCIATE EDITOR M.non W0LFENDEN, Provincial Archives, Vktoria. ADVISORY BOARD 3. C. Goouuow, Princeton. W. N. SAGE, Vancouver. Editorial communications should be addressed to the Editor. Subscriptions should be sent to the Provincial Archives, Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. Price, 5O the copy, or $2 the year. Members of the British Columbia Historical Association in good standing receive the Quarterly without further charge. Neither the Provincial Archives nor the British Columbia Historical Association assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors to the magazine. BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY “Any country worthy of a future should be interested in its past.” VOL. XVIII VIcToRIA, B.C., JULY-OCTOBER, 1954 Nos. 3 and 4 CONThNTS PAGE John Tod: “Career of a Scotch Boy.” Edited, with an introduction and notes, by Madge Wolfenden 133 Rumours of Confederate Privateers Operating in Victoria, Vancouver Island. By Benjamin F. Gilbert 239 NOTES AND CoMMENTs: British Columbia Historical Association 257 Okanagan Historical Society 261 Rossland Historical Museum 263 Plaque Commemorating Fort Langley Pioneer Cemetery 264 Midway Historical Marker 265 John S. Ewart Memorial Fund 265 Contributors to This Issue 266 THE NORTHWEST BOOKSHELF: Cumberland House Journals and inland Journals, 1775—82. Second Series, 1779—82. By Willard E. Ireland — 267 Canada’s Tomorrow: Papers and Discussions, Canada’s Tomorrow Conference. ByJohnTupperSaywell 268 The North Peace River Parish, Diocese of Caledonia: A Brief History. -

Opening an Arctic Escape Route: the Bellot Strait Expedition Adam

Opening an Arctic Escape Route: The Bellot Strait Expedition Adam Lajeunesse and P. Whitney Lackenbauer During the second half of the 1950s, Canadian and American vessels surged into the North American Arctic to establish military installations and to chart northern waters. This article narrates the expeditions by the eastern and western units of the Bellot Strait hydrographic survey group in 1957, explaining how these “modern explorers” grappled with unpredictable ice conditions, weather, and extreme isolation to chart a usable Northwest Passage for deep- draft ships. The story also serves as a reminder of the enduring history of US Coast Guard and Navy operations in Canada’s Arctic waters in collaboration with their Canadian counterparts. Au cours de la deuxième moitié des années 1950, des navires canadiens et américains ont envahi l’Arctique nord-américain pour y établir des installations militaires et cartographier les eaux du Nord. Le présent article traite des expéditions des unités est et ouest du groupe de levés hydrographiques du détroit de Bellot en 1957 et explique comment ces « explorateurs modernes » ont été confrontés à des états de glace imprévisibles, à des conditions météorologiques et à un isolement extrême en traçant un passage du Nord-Ouest utilisable pour les navires à forts tirants d’eau. Le récit nous rappelle également l’histoire durable des opérations de la Garde côtière et de la Marine américaines dans les eaux arctiques du Canada en collaboration avec leurs homologues canadiens. In 1957, the construction of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line string of Arctic radar stations entered its third season and the US Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS) – which had been created eight years earlier to control, operate, and administer ocean transportation for the American military services – prepared The Northern Mariner / Le marin du nord 31, no.