Gothic Undercurrents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorne's Concept of the Creative Process Thesis

48 BSI 78 HAWTHORNE'S CONCEPT OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Retta F. Holland, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HAWTHORNEIS DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER 1 II. PREPARATION FOR CREATIVITY: PRELIMINARY STEPS AND EXTRINSIC CONDITIONS 21 III. CREATIVITY: CONDITIONS OF THE MIND 40 IV. HAWTHORNE ON THE NATURE OF ART AND ARTISTS 67 V. CONCLUSION 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii CHAPTER I HAWTHORNE'S DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER Early in his life Nathaniel Hawthorne decided that he would become a writer. In a letter to his mother when he was seventeen years old, he weighed the possibilities of entering other professions against his inclinations and concluded by asking her what she thought of his becoming a writer. He demonstrated an awareness of some of the disappointments a writer must face by stating that authors are always "poor devils." This realistic attitude was to help him endure the obscurity and lack of reward during the early years of his career. As in many of his letters, he concluded this letter to his mother with a literary reference to describe how he felt about making a decision that would determine how he was to spend his life.1 It was an important decision for him to make, but consciously or unintentionally, he had been pre- paring for such a decision for several years. The build-up to his writing was reading. Although there were no writers on either side of Hawthorne's family, there was a strong appreciation for literature. -

The Purloined Life of Edgar Allan Poe by Jeffrey Steinberg Edgar Allan Poe

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 15, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2006 EDGAR ALLAN POE and the Spirit of the American Republic The Purloined Life Of Edgar Allan Poe by Jeffrey Steinberg Edgar Allan Poe great deal of what people think they know about dark side, and the dark side is that most really creative Edgar Allan Poe, is wrong. Furthermore, there geniuses are insane, and usually something bad comes of Ais not that much known about him—other than them, because the very thing that gives them the talent to that people have read at least one of his short stories, or be creative is what ultimately destroys them. poems; and it’s common even today, that in English liter- And this lie is the flip-side of the argument that most ature classes in high school—maybe upper levels of ele- people don’t have the “innate talent” to be able to think; mentary school—you’re told about Poe. And if you ever most people are supposed to accept the fact that their lives got to the point of being told something about Poe as an are going to be routine, drab, and ultimately insignificant actual personality, you have probably heard some sum- in the long wave of things; and when there are people mary distillation of the slanders about him: He died as a who are creative, we always think of their creativity as drunk; he was crazy; he was one of these people who occurring in an attic or a basement, or in long walks demonstrate that genius and creativity always have a alone in the woods; that creativity is not a social process, but something that happens in the minds of these ran- __________ domly born madmen or madwomen. -

The Scarlet Letter

THE SCARLET LETTER Nathaniel Hawthorne WHO WAS NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE? 1804-1864 Born in Salem, Massachusetts only child father died in 1804, while at sea he and his mother moved in with wealthy uncles leg injury kept Nathaniel down for several months, during this time he read as much as possible and decided to become a writer 1821-1825 – attended Bowdoin College met Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Franklin Pierce (14th President) not a great student WHO WAS NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE? Early ancestor, William Hathorne, first came to America in 1630, settled in Salem, Massachusetts, was a judge known for harsh judgements William’s son John, Hathorne was one of the three judges during the Salem Witch Trials in the 1690s Nathaniel added a “w” to his last name to distance himself from that side of the family WHO WAS NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE? Met Sophia Peabody a painter illustrator transcendentalist Spent time at Brook Farm community met Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau Married Sophia on July 9, 1842 Settled in Concord, Massachusetts 3 Children SETTING Books are like boats on a river… We must look at two parts of the river when learning about the setting of the book. Where the author lives or lived on the river. Where the book takes place along the river. SETTING Transcendentalism was a philosophical movement that was developing by the late 1820s and '30s in the Eastern region of the United States as a protest against the general state of intellectualism and spirituality. The doctrine of the Unitarian church as taught at Harvard Divinity School was of particular concern. -

Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Business Men by Elbert Hubbard

LITTLE JOURNEYS TO THE HOMES OF GREAT BUSINESS MEN BY ELBERT HUBBARD JOHN J. ASTOR The man who makes it the habit of his life to go to bed at nine o'clock, usually gets rich and is always reliable. Of course, going to bed does not make him rich--I merely mean that such a man will in all probability be up early in the morning and do a big day's work, so his weary bones put him to bed early. Rogues do their work at night. Honest men work by day. It's all a matter of habit, and good habits in America make any man rich. Wealth is a result of habit. --JOHN JACOB ASTOR LITTLE JOURNEYS Victor Hugo says, ``When you open a school, you close a prison.'' This seems to require a little explanation. Victor Hugo did not have in mind a theological school, nor yet a young ladies' seminary, nor an English boarding-school, nor a military academy, and least of all a parochial institute. What he was thinking of was a school where people--young and old-- were taught to be self-respecting, self-reliant and efficient--to care for themselves, to help bear the burdens of the world, to assist themselves by adding to the happiness of others. Victor Hugo fully realized that the only education that serves is the one that increases human efficiency, not the one that retards it. An education for honors, ease, medals, degrees, titles, position--immunity--may tend to exalt the individual ego, but it weakens the race and its gain on the whole is nil. -

Beyond the American Landscape: Tourism and the Significance of Hawthorne’S Travel Sketches

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 27 (2016) Copyright © 2016 Toshikazu Masunaga. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. Beyond the American Landscape: Tourism and the Significance of Hawthorne’s Travel Sketches Toshikazu MASUNAGA* INTRODUCTION: 1832 After graduating from Bowdoin College in 1825, Nathaniel Hawthorne went back to his hometown, Salem, Massachusetts, where he concentrated on writing in order to become a professional writer. His early masterpieces such as “Young Goodman Brown” and “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” were written during the so-called solitary years from 1825 to 1837, and he viewed those Salem years of his literary apprenticeship as “a form of limbo, a long and weary imprisonment” (Mellow 36). But biographers of Hawthorne point out that this self-portrait of a solitary genius was partly invented by his “self-dramatizations” (E. H. Miller 87) to romanticize his younger days. In fact, he maintained social engagements, and his sister Elizabeth testified that “he was always social” (Stewart 38). He was more active and outgoing than his own fabricated self-image, and he even made several trips with his uncle Samuel Manning as well as by himself.1 While strenuously writing tales, he undertook an American grand tour alone, traveling around New England and upstate New York in 1832. He was one of those tourists who rushed to major tourist destinations of the day such as the Hudson Valley, Niagara Falls, and the White Mountains in order *Professor, Kwansei Gakuin University 1 2 TOSHIKAZU MASUNAGA to spend leisure time and to find cultural significance in the scenic beauty of the American natural landscape. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

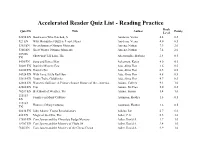

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

Essays on Monkey: a Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Critical and Creative Thinking Program Collection 9-1997 Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone Recommended Citation Ping-I Mao, Isabelle, "Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel" (1997). Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 238. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC . CHINESE NOVEL A THESIS PRESENTED by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1997 Critical and Creative Thinking Program © 1997 by Isabelle Ping-I Mao All rights reserved ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL A Thesis Presented by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Approved as to style and content by: Delores Gallo, As ciate Professor Chairperson of Committee Member Delores Gallo, Program Director Critical and Creative Thinking Program ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL September 1997 Isabelle Ping-I Mao, B.A., National Taiwan University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Delores Gallo Monkey is one of the masterpieces in the genre of the classic Chinese novel. -

Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation from God and Man

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man. Lloyd Moore Daigrepont Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Daigrepont, Lloyd Moore, "Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3389. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3389 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Novella Salon

NOVELLA SALON MARCH 19, 2018 1 NOVELLA OPENING Crybaby in Love For my seventh birthday I asked my parents for a Gameboy. We lived in the middle of nowhere, New Hampshire, and during the summers swarms of mosquitos that bred in our community pools and ponds reserved playing outside as an activity for the fearless or idiotic. I had never asked for a toy as expensive as a Gameboy before, because my mom stayed home to play with me instead of having a job, and I didn’t want her to think she wasn’t enough for me when I was enough for her. But the delight in reading old library books to her inevitably faded, and at school during lunch all the kids would crowd around their Gameboys playing with each other, a club I desperately wanted to join. A week before my birthday, while my parents were out playing ping-pong at the church, I moved a chair around the house, stop- ping to examine all the upper shelves in our closests. I found the 2 Gameboy box hastily tucked under some blankets, as if it were napping until the big reveal. My glee betrayed me and when my parents stepped through the door I ran to wrap my arms around their knees, surprising all three of us. I found the Gameboy! I said, and my parents looked at each other, before my mom replied, Well, I’ll just make sure your card contains all the surprise this year! Since we moved to America, every 1st of June my mom would cut a heart out of a manila folder and use whatever office supplies we had lying around to draw my current obsession—aquariums, the red candy flakes I sometimes ate as a snack, Clifford the big red dog—but more importantly, write “Happy Birthday Bao Bao! I love you.” By this time PBS Kids had taught me “I love you” was something American families said to each other, but I had lived more of my life Chinese, and my parents even more so, so I never asked them to say it. -

Contributors

CONTRIBUTORS Lisa Badner has published poems in TriQuarterly, Mudlark, Fourteen Hills and forthcoming in The Cape Rock. She studies with Phillip Schultz in the NYC Master Class of The Writers Studio. She cycles everywhere and lives in Brooklyn with her kid and partner. Martine Bellen’s most recent books are Ghosts! and 2X(squared). The Wabac Machine (Furniture Press Books) is forthcoming in 2013. Lucy Biederman is doctoral student in English Literature at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. She is the author of a chapbook, The Other World (Danc- ing Girl Press). Her poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in ILK, Shampoo, Gargoyle, and Many Mountains Moving. Richard Brautigan (1935-1984) was an American writer popular during the late 1960s and early 1970s and is often noted for using humor and emotion to pro- pel a unique vision of hope and imagination throughout his body of work which includes ten books of poetry, eleven novels, one collection of short stories, and miscellaneous non-fiction pieces. His easy-to-read yet idiosyncratic prose style is seen as the best characterization of the cultural electricity prevalent in San Fran- cisco, Brautigan’s home, during the ebbing of the Beat Generation and the emer- gence of the counterculture movement. Brautigan’s best-known works include his novel, Trout Fishing in America (1967), his collection of poetry, The Pill versus The Springhill Mine Disaster (1968), and his collection of stories, Revenge of the Lawn (1971). Stephen Campiglio’s poems have recently appeared in Marco Polo Arts Maga- zine, Off the Coast, New England Jazz History Database, and the anthology, New Hungers for Old: One-Hundred Years of Italian American Poetry. -

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop —>

MOTHER MARY ALPHONSA —> ROSE HAWTHORNE LATHROP —> MRS. GEORGE PARSONS LATHROP —> ROSE HAWTHORNE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Rose Hawthorne HDT WHAT? INDEX ROSE HAWTHORNE MOTHER MARY ALPHONSA 1851 May 20, Tuesday: At the “little Red House” in Lenox, Massachusetts, Rose Hawthorne was born to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne. At least subsequent to this period, it seems likely that Nathaniel and Sophia no longer had sexual intercourse, as Nathaniel has been characterized by one of his contemporaries as deficient “in the power or the will to show his love. He is the most undemonstrative person I ever knew, without any exception. It is quite impossible for me to imagine his bestowing the slightest caress upon Mrs. Hawthorne.” Sophia once commented about her husband that he “hates to be touched more than anyone I ever knew.” Presumably the Hawthornes gave up sexual intercourse for purposes of contraception, or perhaps because they found solitary or mutual masturbation to be more congenial, or perhaps, in Nathaniel’s case, because he preferred to have sex with prostitutes, a social practice of the times which Hawthorne referred to as “his illegitimate embraces,” rather than go to the trouble of arranging “blissful interviews” with his wife.1 Hawthorne was bothered by the presence of children, and after the birth of Rose would speak bitterly of the parent’s “duty to sacrifice all the green margin of our lives to these children” towards which he never felt the slightest “natural partiality”: [T]hey have to prove their claim to all the affection they get; and I believe I could love other people’s children better than mine, if I felt they deserved it more.