40736 Biodiversity Strategy 2010-2020 FINAL PROOF.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dwarf Freshwater Crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River Drainages, South-Eastern Queensland Robert B

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Nature 56 (2) © Queensland Museum 2013 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 0079-8835 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Director. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site www.qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum The distribution, ecology and conservation status of Euastacus urospinosus Riek, 1956 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae), a dwarf freshwater crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River drainages, south-eastern Queensland Robert B. MCCORMACK Australian Aquatic Biological Pty Ltd, Karuah, NSW 2324. Email: [email protected] Paul VAN DER WERF Earthan Group Pty Ltd, Ipswich, Collinwood Park, Qld 4301 Citation: McCormack, R.B. & Van der Werf, P. 2013 06 30. The distribution, ecology and conservation status of Euastacus urospinosus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae), a dwarf freshwater crayfish from the Mary and Brisbane River drainages, south-eastern Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum — Nature 56(2): 639–646. Brisbane. ISSN 0079–8835. ABSTRACT The Maleny Crayfish Euastacus urospinosus has previously only been recorded from Boo - loumba and Obi Obi Creeks, Mary River, Queensland. -

Citizens & Reef Science

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Report Editor: Jennifer Loder Report Authors and Contributors: Jennifer Loder, Terry Done, Alex Lea, Annie Bauer, Jodi Salmond, Jos Hill, Lionel Galway, Eva Kovacs, Jo Roberts, Melissa Walker, Shannon Mooney, Alena Pribyl, Marie-Lise Schläppy Science Advisory Team: Dr. Terry Done, Dr. Chris Roelfsema, Dr. Gregor Hodgson, Dr. Marie-Lise Schläppy, Jos Hill Graphic Designers: Manu Taboada, Tyler Hood, Alex Levonis This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this licence visit: http:// This project is supported by Reef Check creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Australia, through funding from the Australian Government. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Reef Check Foundation Ltd, PO Box 13204 George St Brisbane QLD 4003, Project achievements have been made [email protected] possible by a countless number of dedicated volunteers, collaborators, funders, advisors and industry champions. Citation: Thanks from us and our oceans. Volunteers, Staff and Supporters of Reef Check Australia (2015). Authors J. Loder, T. Done, A. Lea, A. Bauer, J. Salmond, J. Hill, L. Galway, E. Kovacs, J. Roberts, M. Walker, S. Mooney, A. Pribyl, M.L. Schläppy. Citizens & Reef Science: A Celebration of Reef Check Australia’s volunteer reef monitoring, education and conservation programs 2001- 2014. Reef Check Foundation Ltd. Cover photo credit: Undersea Explorer, GBR Photo by Matt Curnock (Russell Island, GBR) 3 Key messages FROM REEF CHECK AUSTRALIA 2001-2014 WELCOME AND THANKS • Reef monitoring is critical to understand • Across most RCA sites there was both human and natural impacts, as well evidence of reef health impacts. -

South East Queensland

YOUR FAMILY’S GUIDE TO EXPLORING OUR NATIONAL PARKS SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND Featuring 78 walks ideal for children Contents A BUSH ADVENTURE A bush adventure with children . 1 Planning tips . 2 WITH CHILDREN As you walk . 4 Sometimes wonderful … As you stop and play . 6 look what can we As you rest, eat and contemplate . 8 This is I found! come again? Great short walks for family outings. 10 awesome! Sometimes more of a challenge … I'm tired/ i need are we hungry/bored the toilet nearly there? Whether the idea of taking your children out into nature fills you with a sense of excited anticipation or nervous dread, one thing is certain – today, more than ever, we are well aware of the benefits of childhood contact with nature: 1. Positive mental health outcomes; 2. Physical health benefits; 3. Enhanced intellectual development; and 4. A stronger sense of concern and care for the environment in later life. Planet Ark – Planting Trees: Just What the Doctor Ordered Above all, it can be fun! But let’s remember … Please don’t let your expectations of what should “If getting our kids out happen as you embark on a bush adventure into nature is a search for prevent you from truly experiencing and perfection, or is one more enjoying what does happen. Simply setting chore, then the belief in the intention to connect your children to a perfection and the chore natural place and discover it alongside defeats the joy.” 2nd Edition - 2017 them is enough. We invite you to enjoy Produced & published by the National Parks Association of Queensland Inc. -

40736 Open Space Strategy 2011 FINAL PROOF.Indd

58 Sunshine Coast Open Space Strategy 2011 Appendix 2: Detailed network blueprint The Sunshine Coast covers over 229,072 ha of land. It contains a diverse range of land forms and settings Existing including mountains, rural lands, rivers, lakes, beaches Local recreation park and diverse communities within a range of urban and District recreation park rural settings. Given the size and complexity of the Sunshine Coast open space, the network blueprint Sunshine Coast wide recreation park provides policy guidance for future planning. It addresses existing shortfalls in open space provision as Sports ground well as planning for anticipated requirements responding Amenity reserve to predicted growth of the Sunshine Coast. Environment reserve The network blueprint has been prepared based on three Conservation estate planning catchments to assist readers. Specific purpose sports The three catchments are: Urban Development Area Sunshine Coast wide – recreation parks, sports under ULDA Act 2007 grounds, specific purpose sports and significant Existing signed recreation trails recreation trails that provide a range of diverse and Regional Non-Urban Land Separating unique experiences for users from across the Sunshine Coast from Brisbane to Sunshine Coast. Caboolture Metropolitan Area Community hub District – recreation parks, sports grounds and Locality of Interest recreation trails that provide recreational opportunities boundary at a district level. There are seven open space planning districts, three rural and four urban. Future !( Upgrade local recreation park Local – recreation parks and recreation trails that !( Upgrade Sunshine Coast wide/ provide for the 32 ‘Localities of Interest’ within the district recreation park Sunshine Coast. !( Local recreation park The network blueprint for each catchment provides an (! District recreation park overview of current performance and future directions by category. -

Report on the Administration of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Reporting Period 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020)

Report on the administration of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (reporting period 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020) Prepared by: Department of Environment and Science © State of Queensland, 2020. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. September 2020 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Nature Conservation Act 1992—departmental administrative responsibilities ............................................................. 1 List of legislation and subordinate legislation .............................................................................................................. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

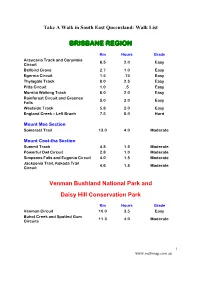

Take A Walk in South East Queensland: Walk List BRISBANE REGION Km Hours Grade Araucaria Track and Corymbia 6.5 2.0 Easy Circuit Bellbird Grove 2.7 1.0 Easy Egernia Circuit 1.5 .75 Easy Thylogale Track 8.0 2.5 Easy Pitta Circuit 1.0 .5 Easy Morelia Walking Track 6.0 2.0 Easy Rainforest Circuit and Greenes 5.0 2.0 Easy Falls Westside Track 5.8 2.0 Easy England Creek – Left Brach 7.5 6.0 Hard Mount Mee Section Somerset Trail 13.0 4.0 Moderate Mount Coot-tha Section Summit Track 4.8 1.5 Moderate Powerful Owl Circuit 2.8 1.0 Moderate Simpsons Falls and Eugenia Circuit 4.0 1.5 Moderate Jacksonia Trail, Kokoda Trail 4.6 1.5 Moderate Circuit Venman Bushland National Park and Daisy Hill Conservation Park Km Hours Grade Venman Circuit 10.0 3.5 Easy Buhot Creek and Spotted Gum 11.3 4.0 Moderate Circuits 1 www.melbmap.com.au Take A Walk in South East Queensland: Walk List Blue Lake National Park Km Hours Grade Tortoise Lagoon and Blue Lake 5.2 2.0 Easy Blue Lake, the Beach and Neem- 13.5 4.0 Mod Beeba Moreton Island National Park Km Hours Grade Desert Walking Track 2.0 1.0 Easy Mount Tempest, Telegraph Track 22.0 8.0 Moderate Circuit Blue Lagoon, Honeyeater Lake Circuit 6.5 2.0 Easy Rous Battery to The Desert 19.6 6.0 Moderate Little Sandhills to Big Sandhills 16.0 5.0 Moderate Mirapool Lagoon 1.0 1.0 Easy SUNSHINE COAST and HINTERLAND Glass House Mountains National Park Km Hours Grade Tibrogargan Circuit 3.3 1.5 Easy Mount Tibrogargan Summit 3.0 3.5 Hard Trachyte Circuit 5.6 2.0 Easy Mount Ngungun Track 1.5 2.0 Moderate Mount Beerwah Summit 2.6 -

2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan: Redlands

Item: Redlands Draft LG Report Date: Last updated 11th November 2014 2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan: Redlands How can the SEQ NRM Plan support the Community’s Vision for the future of Redlands? Supporting Document no. 7 for the 2014 Update of the SEQ Natural Resource Management Plan. Note regards State Government Planning Policy: The Queensland Government is currently undertaking a review of the SEQ Regional Plan 2009. Whilst this review has yet to be finalised, the government has made it clear that the “new generation” statutory regional plans focus on the particular State Planning Policy issues that require a regionally-specific policy direction for each region. This quite focused approach to statutory regional plans compares to the broader content in previous (and the current) SEQ Regional Plan. The SEQ Natural Resource Management Plan has therefore been prepared to be consistent with the State Planning Policy. Disclaimer: This information or data is provided by SEQ Catchments Limited on behalf of the Project Reference Group for the 2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan. You should seek specific or appropriate advice in relation to this information or data before taking any action based on its contents. So far as permitted by law, SEQ Catchments Limited makes no warranty in relation to this information or data. ii Table of Contents Redlands, Bay and Islands ....................................................................................................................... 1 Part A - Achieving the community’s visions for Redlands .................................................................... 1 Queensland Plan – South East Queensland Themes .......................................................................... 1 Regional Development Australia - Logan and Redlands ..................................................................... 1 Services needed from natural assets to achieve these Visions .......................................................... 2 Natural Assets depend on the biodiversity of the Redlands. -

Submission Re Proposed Cooloola World Heritage Area Boundary

Nearshore Marine Biodiversity of the Sunshine Coast, South-East Queensland: Inventory of molluscs, corals and fishes July 2010 Photo courtesy Ian Banks Baseline Survey Report to the Noosa Integrated Catchment Association, September 2010 Lyndon DeVantier, David Williamson and Richard Willan Executive Summary Nearshore reef-associated fauna were surveyed at 14 sites at seven locations on the Sunshine Coast in July 2010. The sites were located offshore from Noosa in the north to Caloundra in the south. The species composition and abundance of corals and fishes and ecological condition of the sites were recorded using standard methods of rapid ecological assessment. A comprehensive list of molluscs was compiled from personal observations, the published literature, verifiable unpublished reports, and photographs. Photographic records of other conspicuous macro-fauna, including turtles, sponges, echinoderms and crustaceans, were also made anecdotally. The results of the survey are briefly summarized below. 1. Totals of 105 species of reef-building corals, 222 species of fish and 835 species of molluscs were compiled. Thirty-nine genera of soft corals, sea fans, anemones and corallimorpharians were also recorded. An additional 17 reef- building coral species have been reported from the Sunshine Coast in previous publications and one additional species was identified from a photo collection. 2. Of the 835 mollusc species listed, 710 species could be assigned specific names. Some of those not assigned specific status are new to science, not yet formally described. 3. Almost 10 % (81 species) of the molluscan fauna are considered endemic to the broader bioregion, their known distribution ranges restricted to the temperate/tropical overlap section of the eastern Australian coast (Central Eastern Shelf Transition). -

Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas of Inshore Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia

Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas of Inshore Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia By: Chris Roelfsema1,2, Jennifer Loder2, Rachel Host2, and Eva Kovacs1,2 1) Remote Sensing Research Centre (RSRC), School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, AUSTRALIA, 4072 2) Reef Check Australia, 9/10 Thomas St West End Queensland, AUSTRALIA 4101 January 2017 This project is supported by Reef Check Australia, Healthy Waterways and Catchments and The University of Queensland’s Remote Sensing Research Centre through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme, Port of Brisbane Community Grant Program and Redland City Council. We would like to thank the staff and volunteers who supported this project, including: Nathan Caromel, Amanda Delaforce, John Doughty, Phil Dunbavan, Terry Farr, Sharon Ferguson, Stefano Freguia, Rachel Host, Tony Isaacson, Eva Kovacs, Jody Kreuger, Angela Little, Santiago Mejia, Rebekka Pentti, Alena Pribyl, Jodi Salmond, Julie Schubert, Douglas Stetner, Megan Walsh. A note of appreciation to the Moreton Bay Research Station and Moreton Bay Environmental Education Centre for their support in fieldwork logistics, and, to Satellite Application Centre for Surveying and Mapping (SASMAC) for providing the ZY-3 imagery. Project activities were conducted on the traditional lands of the Quandamooka People. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land, of Elders past and present. They are the Nughi of Moorgumpin (Moreton Island), and the Nunukul and Gorenpul of Minjerribah. Report should be cited as: C. Roelfsema, J. Loder, R. Host and E. Kovacs (2017). Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas of Inshore Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia, Brisbane. Remote Sensing Research Centre, School of Geography, Environmental Management and Planning, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; and Reef Check Australia, Brisbane, Australia. -

Recovery Plan for the Coxen's Fig-Parrot Cyclopsitta Diophthalma Coxeni (Gould)

Approved NSW Recovery Plan Recovery Plan for the Coxen's Fig-Parrot Cyclopsitta diophthalma coxeni (Gould) JulyNSW National 2002 Parks and Wildlife Service Page © NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, 2002. This work is copyright. However, material presented in this plan may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, providing that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Apart from this and any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from NPWS. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service 43 Bridge Street (PO Box 1967) Hurstville NSW 2220 Tel: 02 9585 6444 www.npws.nsw.gov.au Requests for information or comments regarding the recovery program for the Coxen's Fig-Parrot are best directed to: The Coxen's Fig-Parrot Recovery Coordinator Threatened Species Unit, Northern Directorate NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Locked Bag 914 Coffs Harbour NSW 2450 Tel 02 6651 5946 Cover illustration: Sally Elmer with technical assistance from John Young This plan should be cited as follows: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (2002). Approved Recovery Plan for the Coxen's Fig-Parrot Cyclopsitta diophthalma coxeni (Gould), NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Hurstville. ISBN 0 7313 6893 2 Approved NSW Recovery Plan Coxen’s Fig-Parrot Recovery Plan for the Coxen's Fig-Parrot Cyclopsitta diophthalma coxeni (Gould) Executive Summary Introduction Coxen’s Fig-Parrot, Cyclopsitta diophthalma coxeni (Gould), is one of Australia’s rarest and least known birds. Currently known in NSW from only a small number of recent sightings, Coxen’s Fig-Parrot has declined due, at least in part, to the clearing of lowland subtropical rainforest in north-east NSW and south- east Queensland. -

Noosa Shire Recreational Parks

Noosa Shire Recreational Parks Gympie Regional Council Toolara State Forest Cooloola (Noosa River) Resources Reserve H! WOLVI RANGE Great Sandy National Park d a o R n Ki in Dr Pa K ges e R i o p a d m y G Road eek Cr Lake Overton Way Park nd d o a Lak o e Fla m t R Cootharaba R n o ! H KIN KIN i a a K b d a r a h t H! TEEWAH o Kin Kin Arboretum Park o C H! BOREEN POINT Ju Woondum National Park nc Boreen Field Park tio n Ro ad James Mckane Lookout Park Coral Sea Cooloothin Conservation Park H! Mount Pinbarren National Park COOTHARABA ive e r v i D i Woondum Conservation Park Lou s Bazzo r D n o King Park Ringtail State Forest n Greenridge Pinbarren Road Park n H! i Great Sandy Resources Reserve COORAN k c M ad Orana Park Lake Ro reek Cunningham ParkBelwood Park Cooroibah les C Co Depper Park Cooroora Creek Park Yurol State Forest Tuchekoi National Park H! POMONA Cooroora Mountain Park Cooroibah Creek Park Fish Hatchery ParkTewantin National Park Pines Park NOOSA HEADS Noosa Woods Park Noosa Botanic Gardens Daintree Park Read Park Elm S Lions Park tr H! eet Heritage Park TEWANTIN y H! ro Noo d Cedar Gully Bushland Park Coo sa Roa Alec Loveday Park H! Prospect Place Park NOOSAVILLE Blac Cranks Creek Park k Mou ntain Kauri Park H! Road Cooroy Pomona Lions Park Lutheran Ovals Park H! COOROY Eureka Park SUNSHINE BEACH Black Mountain School Park Ashgrove Park B Rainbow Park ru Lenehans Lane ce Lake Weyba H re ig Mount Cooroy Conservation Park C e h Castaways Park lli k R w Be oad a oy y Moonbeam Park or Noosa National Park Co MARCUS BEACH HawthorH!n Park Tuchekoi Conservation Park Podargus Park PEREGIAN BEACH Osprey Park West Cooroy State Forest H! Peregian Beach Park Sunshine Coast Regional Council Legend Recreational Park ± National Park & State Forest 0 1.25 2.5 5 7.5 10 km. -

Brisbane Publishing Date: 2008-03-06 | Country Code: Au 1

ADVERTISING AREA REACH THE TRAVELLER! BRISBANE PUBLISHING DATE: 2008-03-06 | COUNTRY CODE: AU 1. DURING PLANNING 2. DURING PREPARATION Contents: The City, Do & See, Eating, Cafés, Bars & Nightlife, Shopping, Sleeping, Essential Information 3. DURING THE TRIP Advertise under these headings: The City, Do & See, Cafés, Eating, Bars & Nightlife, Shopping, Sleeping, Essential Information, maps Copyright © 2007 Fastcheck AB. All rights reserved. For more information visit: www.arrivalguides.com SPACE Do you want to reach this audience? Contact Fastcheck FOR E-mail: [email protected] RENT Tel: +46 31 711 03 90 Population: 1,735,181 Currency: $1 Australian Dollar (AUD) = 100 cents Opening hours: Opening hours for shops in Brisbane vary but in the city retailers trade 9am-5:30pm Monday to Saturday and 10am-4:30 on Sunday. Internet: www.visitbrisbane.com.au www.discoverbrisbane.com www.ourbrisbane.com Newspapers: The Courier Mail The Australian The Weekend Australian Sunday Mail Quest Newspapers Emergency numbers: Police, fire, ambulance: 000 Poisons Information: +61 (0)7 13 11 26 Qualified health advice: +61 (0)7 13 43 25 84 Tourist information: BRISBANE Visitor Information Centre Address: Queen Street Mall, CBD Brisbane is a lively, cosmopolitan city with excellent Opening times: Mon - Sat 9am-5:30pm. restaurants, beautiful riverside parks, a busy cultural Sunday 9:30am-4:30pm Tel: +61 (0)7 3006 6290 calendar and a great nightlife. Its fantasticweather year-round has allowed outdoor activities to thrive and Brisbane has developed a vibrant cafe culture. The city is surrounded by some of the state’s major tourist attractions, and there is an abundant choice of daytrips whether it be to the coast to the golden beaches, or inland to see some of Queensland’s serene bushland, there is something for everybody.