Tobacco: Deadly in Any Form Or Disguise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No

United States ofAmerica FEDERAL TRADE COM.MISSION Washington, D.C. 20580 Division of Advertising Practices l\1EMORANDUM TO: Public Records Office of the Secretary FROM: Bonnie McGregor Division ofAdvertising Practices DATE: December 22, 2015 SUBJECT: Rotational Health Warnings for Cigarettes File No. P854505 Please place the attached documents on the public record in the above-captioned matter. 1. December 18, 2014 letter from Karen E Delaney, Goodrich Tobacco Company, LLC to Mary K. Engle. 2. January 5, 2015 letter from Mary K. Engle to Karen E Delaney, Goodrich Tobacco Company, LLC. 3. December 23, 2014 letter from Anoush Sarkisyan on behalfof U.S. Cigaronne, Inc. to Mary K. Engle and William Ducklow. 4. January 9, 2015 letter from Mary K. Engle to Anoush Sarkisyan on behalf ofU.S. Cigaronne, Inc. 5. January 26, 2015 letter from Victoria Spier Evans, Vector Tobacco Inc. to Mary K. Engle. 6. February 3, 2015 letter from Mary K. Engle to Victoria Spier Evans, Vector Tobacco Inc. 7. February 3, 2015 letter from Eric F. Facer on behalf of Great Swamp Enterprises, Inc. to Mary K. Engle. 8. February 5, 2015 letter from Mary K. Engle to Eric F. Facer on behalfof Great Swamp Enterprises, Inc. Public Records December 22, 2015 Page 2 9. January 9, 2015 letter from Henry C. Roemer, III on behalf ofKretek International, Inc. to Mary K. Engle. 10. February 9, 2015 letter from Mary K. Engle to Henry C. Roemer, III on behalf of Kretek International, Inc. 11. February 5, 2015 letter from Silvia B. Pifiera-V azquez on behalf of R.G. -

Youth Bidi, Kretek, Or Pipe Tobacco Use

2013 Florida Youth Tobacco Survey: Fact Sheet 10 Youth Bidi, Kretek, or Pipe Tobacco Use Introduction The Florida Youth Tobacco Survey (FYTS) was administered in the spring of 2013 to 6,440 middle school students and 6,175 high school students in 172 public schools throughout the state. The overall survey response rate for middle schools was 83%, and the overall survey response rate for high schools was 75%. The FYTS has been conduct- ed annually since 1998. The data presented in this fact sheet are weighted to represent the entire population of public middle and high school students in Florida. About Bidis, Kreteks, and Pipe Tobacco Bidis are small brown cigarettes from India consisting of tobacco wrapped in a leaf tied together with a thread. Bidis have higher levels of nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar than traditional cigarettes. Kreteks are cigarettes containing tobacco and clove extract. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration banned kreteks, along with flavored cigarettes, from being sold in the United States. Pipe tobacco comes either plain or flavored and is smoked through a pipe. On previous FYTS fact sheets, bidis, kreteks, and pipe tobacco have been Figure 1. Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 8.4 8.5 reported as “specialty tobacco” products. 9 8.0 8 7.2 7.1 Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 7 5.9 6 In 2013, 2.5% of middle school and 5.9% of high 5 4 3.2 school students had tried smoking a bidi, kretek, or Percent 2.9 3.0 3.0 2.5 2.5 pipe tobacco at least once (Figure 1). -

Smoking Behavior and the Use of Cigarette Types Among University Student

E-ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol 10 No 5 ISSN 2239-978X www.richtmann.org September 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Arisona et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Smoking Behavior and the Use of Cigarette Types Among University Student Amalia Arisona Laili Rahayuwati Ayu Prawesti Habsyah Saparidah Agustina Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0100 Abstract The number of smokers is increasing every year in Indonesia. Cigarettes can cause several health problems and can even cause death. Aside from conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes and shisha are starting to get the spotlight. The types of cigarettes include conventional cigarettes, electric cigarettes and shisha can cause health problems to both smokers and the people around them. The purpose of this study was to determine smoking behavior and the use of cigarette types in students. This research was quantitative descriptive. The population in this study were students who have smoked either the conventional, electric or shisha. The sampling technique used was accidental sampling with 384 students as the samples. The instrument in this study used a questionnaire that was independently developed by researchers with a total of 14 questions. The results of the data obtained were then analyzed using descriptive analysis presented in the form of a percentage. Based on the results of the study it was found that non-health students (90.6%) were more likely to smoke than health students (9.4%). -

Bidi, Kretek, Or Pipe Tobacco Use

2012 Florida Youth Tobacco Survey: Fact Sheet 10 Youth Bidi, Kretek, or Pipe Tobacco Use Introduction The Florida Youth Tobacco Survey (FYTS) was administered in the spring of 2012 to 38,989 middle school students and 36,439 high school students in 746 public schools throughout the state. The overall survey response rate for middle schools was 77% and the overall response rate for high schools was 73%. The FYTS has been conducted annually since 1998. The data presented in this fact sheet are weighted to represent the entire population of public middle and high school students in Florida. About Bidis, Kreteks, and Pipe Tobacco Bidis are small brown cigarettes from India consisting of tobacco wrapped in a leaf tied together with a thread. Bidis have higher levels of nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar than traditional cigarettes. Kreteks are cigarettes containing tobacco and clove extract. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration banned kreteks, along with flavored cigarettes, from being sold in the United States. Pipe tobacco comes either plain or flavored and is smoked through a pipe. On previous FYTS fact sheets, bidis, kreteks, and pipe tobacco have been Figure 1. Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 8.4 8.5 reported as “specialty tobacco” products. 9 8.0 8 7.2 7.1 Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 7 6 In 2012, 2.5% of middle school and 7.1% of high 5 4 3.2 school students had tried smoking a bidi, kretek, or Percent 2.9 3.0 3.0 2.5 pipe tobacco at least once (Figure 1). -

Assonance a Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies

ISSN 2394-7853 Assonance A Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies No.21 January 2021 Department of Russian & Comparative Literature University of Calicut Kerala – 673635 Assonance: A Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies No.21, January 2021 ISSN 2394-7853 Listed in UGC Care ©2021 Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut Editors: Dr. K.K. Abdul Majeed (Assistant Professor & Head) Dr. Nagendra Shreeniwas (Associate Professor, CRS, SLL&CS, JNU, New Delhi) Sub Editor: Sameer Babu Kavad Board of Referees: 1. Prof. Amar Basu, (Retd.), JNU, New Delhi 2. Prof. Govindan Nair (Retd.), University of Kerala 3. Prof. Ranjana Banerjee, JNU, New Delhi 4. Prof. Kandrapa Das, Guahati University, Assam 5. Prof. Sushant Kumar Mishra, JNU, New Delhi 6. Prof. T.K. Gajanan, University of Mysore 7. Prof. Balakrishnan K, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi 8. Dr. S.S. Rajput, EFLU, Hyderabad 9. Smt. Sreekumari S, (Retd.), University of Calicut, Kerala 10. Dr. V.K. Subramanian, University of Calicut, 11. Dr. Arunim Bandyopadhyay, JNU, New Delhi 12. Dr. K.M. Sherrif, University of Calicut, Kerala 13. Dr. K.M. Anil, Malayalam University, Kerala 14. Dr. Sanjay Kumar, EFLU, Hyderabad 15. Dr. Krishnakumar R.S, University of Kerala Frequency: Annual Published by: Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut, Thenhipalam, Malappuram, Kerala – 673635 Articles in the journal reflect the views of the respective authors only and do not reflect the view of the editors, the journal, the department and/or the university. ii Notes for contributors Assonance is an ISSN, UGC-CARE listed, multilingual, refereed, blind peer reviewed, annual publication of the Department of Russian & Comparative Literature, University of Calicut. -

Altria.Com/Proxy

6601 West Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23230 Dear Fellow Shareholder: It is my pleasure to invite you to join us at the 2016 Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Altria Group, Inc. to be held on Thursday, May 19, 2016 at 9:00 a.m., Eastern Time, at the Greater Richmond Convention Center, 403 North 3rd Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219. At this year’s meeting, we will vote on the election of 11 directors, the ratification of the selection of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP as the Company’s independent registered public accounting firm and, if properly presented, two shareholder proposals. We will also conduct a non-binding advisory vote to approve the compensation of the Company’s named executive officers. There also will be a report on the Company’s business, and shareholders will have an opportunity to ask questions. To attend the meeting, an admission ticket and government-issued photo identification are required. To request an admission ticket, please follow the instructions on page 9 in response to Question 16. One immediate family member who is 21 years of age or older may accompany a shareholder as a guest. We use the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule that allows companies to furnish proxy materials to their shareholders over the Internet. We believe this expedites shareholders receiving proxy materials, lowers costs and conserves natural resources. We thus are mailing to many shareholders a Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials, rather than a paper copy of the Proxy Statement and our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2015. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

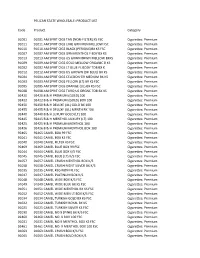

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

Cigarette Smoking-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches

Cigarette Smoking-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tamer M. Abdelghany Graduate Program in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jay L. Zweier, MD, Advisor Dr. Arthur Strauch III, PhD Dr. Amal Amer, MD PhD Copyright by Tamer M. Abdelghany 2013 Abstract Cigarette smoking (CS) remains the single largest preventable cause of death. Worldwide, smoking causes more than five million deaths annually and, according to the current trends, smoking may cause up to 10 million annual deaths by 2030. In the U.S. alone, approximately half a million adults die from smoking-related illnesses each year which represents ~ 19% of all deaths in the U.S., and among them 50,000 are killed due to exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS). Smoking is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). The crucial event of The CVD is the endothelial dysfunction (ED). Despite of the vast number of studies conducted to address this significant health problem, the exact mechanism by which CS induces ED is not fully understood. The ultimate goal of this thesis; therefore, is to study the mechanisms by which CS induces ED, aiming at the development of new therapeutic strategies that can be used in protection and/or reversal of CS-induced ED. In the first part of this study, we developed a well-characterized animal model for chronic secondhand smoke exposure (SHSE) to study the onset and severity of the disease. -

A Global Review of Country Experiences Tobacco Tax Administration: a Perspective from the Imf

: TRADE A GLOBAL REVIEW OF COUNTRY EXPERIENCES TOBACCO TAX ADMINISTRATION: A PERSPECTIVE FROM THE IMF TECHNICAL REPORT OF THE WORLD BANK GROUP GLOBAL TOBACCO CONTROL PROGRAM. CONFRONTING EDITOR: SHEILA DUTTA ILLICIT TOBACCO TOBACCO TAX ADMINISTRATION 22 TOBACCO TAX ADMINISTRATION A Perspective from the IMF Janos Nagy1 Chapter Summary Illegal cultivation, production, and trade are a widespread problem associated with tobacco products, given their easy portability and the high profit margins. A single container or truck- load of illegal cigarettes can yield up to US$2 million in profits. The annual revenue loss in tobacco taxation worldwide is estimated at roughly US$40 billion–US$50 billion, that is, the equivalent of about 10 percent of global cigarette consumption. Tobacco products are susceptible to bootlegging, smuggling, and fraud, especially excise fraud, which extends from standard customs and commercial fraud to undeclared activities such as the diversion of legally produced cigarettes from international transit routes directly to retail markets, the illegal domestic production and sale of cigarettes, and legal or illegal production for export. Illegal trade is a context-specific activity, and administrative and control measures need to be tailored to this context. Understanding the size, characteristics, and patterns of illegal pro- duction and trade is a prerequisite to developing effective antifraud strategies. Regional and international coordination can substantially improve the efficiency of national efforts. The central concern in the administration of value added taxes and excise taxes on tobacco is to control the import, production, and distribution of taxed products tightly. This control 1 Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund (IMF). -

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed from the California Tobacco Directory by Brand

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Brand Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed #117 - RYO National Tobacco Company 10/21/2011 5/6/05 Man. Change from RBJ to National Tobacco Company 10/20's (ten-twenty's) M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 2/2/05 Man. Name change from Dhanraj Imports, Inc. 10/20's (ten-twenty's) - RYO M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 1st Choice R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Removed 5/2/08; Reinstated 7/11/08 32 Degrees General Tobacco 2/28/2010 4 Aces - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/12/2010 A Touch of Clove Sherman 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. Inc. 9/25/2009 AB Rimboche' - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Ace King Maker Marketing 5/21/2020 All American Value Philip Morris, USA 5/5/2006 All Star Liberty Brands, LLC 5/5/2006 Alpine Philip Morris, USA 8/14/2013 Removed 5/4/07; Reinstated 5/8/09 Always Save Liberty Brands, LLC 5/4/2007 American R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/6/2005 American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC 9/22/2015 American Blend Mac Baren Tobacco Company 5/4/2007 American Harvest Sandia Tobacco Manufacturers, Inc. 8/31/2016 American Harvest - RYO Truth & Liberty Manufacturing 8/2/2016 American Liberty Les Tabacs Spokan 5/12/2006 Amphora - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/18/2011 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Arango Sportsman - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Arbo - RYO VCT 5/4/2007 Ashford Von Eicken Group 5/8/2009 Ashford - RYO Von Eicken Group 12/23/2011 Athey (Old Timer's) Daughters & Ryan, Inc. -

The Filter Fraud: Debunking the Myth of “Safer” As a Key New Strategy Of

THE FILTER FRAUD: DEBUNKING THE MYTH OF “SAFER” AS A KEY NEW STRATEGY OF TOBACCO CONTROL Alan Blum, MD, University of Alabama Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA ([email protected]) Thomas E. Novotny, MD MPH, San Diego State University, Cigarette Butt Pollution Project, San Diego, CA, USA ([email protected]) Background Filters are a Health Hazard Although efforts have been made to eliminate the use of misleading • As with flavorings such as menthol, filters facilitate nicotine descriptors such as “low tar,” “lights,” and “mild” from cigarette addiction by making smoking less harsh and thus easier for marketing, the elimination of the cigarette filter, which is on 99.7% youth to start smoking. For existing smokers, the tobacco of cigarettes sold in United States, has been largely overlooked as a industry fostered consumer complacency and false security tobacco control strategy. The 2014 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on about the implied protection that the filter could confer, the Health Consequences of Smoking and the 2001 U.S. National diminishing the urgency to quit smoking. Cancer Institute Monograph 13 report that the near-universal • Lung cancer risks among smokers have doubled for men and adoption by smokers of filtered cigarettes since their introduction in increased by almost 10 times for women from 1960-1980; the 1930s has not reduced these consumers’ risks for cancer and relative risks for and incidence of the more aggressive other diseases (1). Moreover, the non-biodegradable filter is the adenocarcinoma increased from 4.6 to19.0 among men and from main component of tobacco product waste in the environment.