Assonance a Journal of Russian & Comparative Literary Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Offices

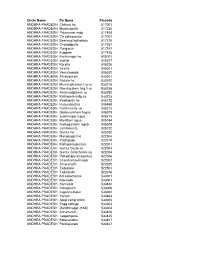

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

News Analysis

Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2009.034454 on 2 December 2009. Downloaded from KAZAKHSTAN: PUBLIC SMOKING BAN News analysis Like Bulgaria (see page 429), just a few years ago Kazakhstan would not have been NEW ZEALAND: INDUSTRY FACES GRILLING URUGUAY: NEW HEALTH WARNINGS expected to turn up on a list of countries OVER MAORIS Uruguay is set to have the largest health likely to ban smoking in all public places. In which country might one hear the warnings in the world. A new set of six But as the health ministry said when most refreshingly straight talk about the graphic pack warnings, each covering 80 announcing such a move in September, tobacco industry in the national legisla- per cent of the front and back of the pack, the central Asian country is now following the recommendations of the World Health ture? There may be no easy, single was finalised in September. They will Organization, according to whose data answer, but recent experience suggests have to be in place by 1 March 2010, more than 30,000 people die every year in that New Zealand must be a contender. though the warnings they replace, which Kazakhstan from smoking. Sports stadiums While the majority of New Zealanders covered 50 per cent of the pack, were and public transport facilities were already have been reducing their tobacco con- ordered to be expanded to 80 per cent by smoke-free, but Kazakh bars and night- sumption for several decades, the indigen- December. The two large sides of the pack clubs, and all other remaining public areas ous Maori people still have alarmingly are not the only place where Uruguayan not previously covered by the ban, have high smoking rates. -

Youth Bidi, Kretek, Or Pipe Tobacco Use

2013 Florida Youth Tobacco Survey: Fact Sheet 10 Youth Bidi, Kretek, or Pipe Tobacco Use Introduction The Florida Youth Tobacco Survey (FYTS) was administered in the spring of 2013 to 6,440 middle school students and 6,175 high school students in 172 public schools throughout the state. The overall survey response rate for middle schools was 83%, and the overall survey response rate for high schools was 75%. The FYTS has been conduct- ed annually since 1998. The data presented in this fact sheet are weighted to represent the entire population of public middle and high school students in Florida. About Bidis, Kreteks, and Pipe Tobacco Bidis are small brown cigarettes from India consisting of tobacco wrapped in a leaf tied together with a thread. Bidis have higher levels of nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar than traditional cigarettes. Kreteks are cigarettes containing tobacco and clove extract. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration banned kreteks, along with flavored cigarettes, from being sold in the United States. Pipe tobacco comes either plain or flavored and is smoked through a pipe. On previous FYTS fact sheets, bidis, kreteks, and pipe tobacco have been Figure 1. Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 8.4 8.5 reported as “specialty tobacco” products. 9 8.0 8 7.2 7.1 Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 7 5.9 6 In 2013, 2.5% of middle school and 5.9% of high 5 4 3.2 school students had tried smoking a bidi, kretek, or Percent 2.9 3.0 3.0 2.5 2.5 pipe tobacco at least once (Figure 1). -

Illicit Tobacco Trade in Georgia: Prevalence and Perceptions Megan Little,1 Hana Ross,1 George Bakhturidze ,2,3 Iago Kachkachishvili4

Original research Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054839 on 18 January 2019. Downloaded from Illicit tobacco trade in Georgia: prevalence and perceptions Megan Little,1 Hana Ross,1 George Bakhturidze ,2,3 Iago Kachkachishvili4 ► Additional material is ABSTRact The new government coming to power in 2004 published online only. To view Background In lower- income and middle- income decided to double and triple taxes for imported please visit the journal online filtered and domestic filtered cigarettes, respec- (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ countries, limited research exists on illicit tobacco tobaccocontrol- 2018- 054839). trade and its responsiveness to taxation. Tobacco taxes tively. In preparation for this increase, tobacco are critical in reducing tobacco consumption, thereby companies prepurchased tax stamps (introduced in 1 Economics, Southern Africa improving public health. However, the tobacco industry 1999) with the lower 2004 value, to use in their Labour and Development 2005 sales. This resulted in an artificial tax revenue Research Unit, University of claims that tax increases will increase illicit tobacco Cape Town, Cape Town, South trade. Therefore, research evidence on the size of the increase in 2004 followed by a sharp fall in early Africa illicit cigarette market is needed in Georgia and other 2005, when the new tax came into effect. Tobacco 2 Tobacco Control Research, low- income and middle- income countries to inform companies then asserted that the tax revenue fall FCTC Implementation and tobacco tax policies. was driven by a sharp increase in illicit trade from Monitoring Center in Georgia, 10% in 2003 to 65% in post-2005.3 This persuaded Tbilisi, Georgia Methods In 2017, a household survey using stratified 3Health Promotion Research, multistage sampling was conducted in Georgia with the government to lower taxes by 30%–40% in Georgian Health Promotion and 2997 smokers, to assess illicit tobacco consumption. -

NOTIFICATION for the POSTS of GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respective R

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE RECTT/50-1/DLGS/2019 Applications are invited by the respective recruiting authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’ against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of GDS Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device, ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the GDS Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same GDS Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM etc.In some of the Branch Post Offices, the BPM has to do all the work of BPM/ABPM. -

Bidi, Kretek, Or Pipe Tobacco Use

2012 Florida Youth Tobacco Survey: Fact Sheet 10 Youth Bidi, Kretek, or Pipe Tobacco Use Introduction The Florida Youth Tobacco Survey (FYTS) was administered in the spring of 2012 to 38,989 middle school students and 36,439 high school students in 746 public schools throughout the state. The overall survey response rate for middle schools was 77% and the overall response rate for high schools was 73%. The FYTS has been conducted annually since 1998. The data presented in this fact sheet are weighted to represent the entire population of public middle and high school students in Florida. About Bidis, Kreteks, and Pipe Tobacco Bidis are small brown cigarettes from India consisting of tobacco wrapped in a leaf tied together with a thread. Bidis have higher levels of nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar than traditional cigarettes. Kreteks are cigarettes containing tobacco and clove extract. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration banned kreteks, along with flavored cigarettes, from being sold in the United States. Pipe tobacco comes either plain or flavored and is smoked through a pipe. On previous FYTS fact sheets, bidis, kreteks, and pipe tobacco have been Figure 1. Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 8.4 8.5 reported as “specialty tobacco” products. 9 8.0 8 7.2 7.1 Ever Tried Bidis, Kreteks, or Pipe Tobacco 7 6 In 2012, 2.5% of middle school and 7.1% of high 5 4 3.2 school students had tried smoking a bidi, kretek, or Percent 2.9 3.0 3.0 2.5 pipe tobacco at least once (Figure 1). -

(With) Shakespeare (/783437/Show) (Pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/Pdf) Klett

11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation ISSN 1554-6985 V O L U M E X · N U M B E R 2 (/current) S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 (/previous) S h a k e s p e a r e a n d D a n c e E D I T E D B Y (/about) E l i z a b e t h K l e t t (/archive) C O N T E N T S Introduction: Dancing (With) Shakespeare (/783437/show) (pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/pdf) Klett "We'll measure them a measure, and be gone": Renaissance Dance Emily Practices and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (/783478/show) (pdf) Winerock (/783478/pdf) Creation Myths: Inspiration, Collaboration, and the Genesis of Amy Romeo and Juliet (/783458/show) (pdf) (/783458/pdf) Rodgers "A hall, a hall! Give room, and foot it, girls": Realizing the Dance Linda Scene in Romeo and Juliet on Film (/783440/show) (pdf) McJannet (/783440/pdf) Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet: Some Consequences of the “Happy Nona Ending” (/783442/show) (pdf) (/783442/pdf) Monahin Scotch Jig or Rope Dance? Choreographic Dramaturgy and Much Emma Ado About Nothing (/783439/show) (pdf) (/783439/pdf) Atwood A "Merry War": Synetic's Much Ado About Nothing and American Sheila T. Post-war Iconography (/783480/show) (pdf) (/783480/pdf) Cavanagh "Light your Cigarette with my Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Madhavi Dances and a Golden-hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara Biswas (2006) (/783482/show) (pdf) (/783482/pdf) www.borrowers.uga.edu/7165/toc 1/2 11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation The Concord of This Discord: Adapting the Late Romances for Elizabeth the -

Anthropology of Tobacco

Anthropology of Tobacco Tobacco has become one of the most widely used and traded commodities on the planet. Reflecting contemporary anthropological interest in material culture studies, Anthropology of Tobacco makes the plant the centre of its own contentious, global story in which, instead of a passive commodity, tobacco becomes a powerful player in a global adventure involving people, corporations and public health. Bringing together a range of perspectives from the social and natural sciences as well as the arts and humanities, Anthropology of Tobacco weaves stories together from a range of historical, cross-cultural and literary sources and empirical research. These combine with contemporary anthropological theories of agency and cross-species relationships to offer fresh perspectives on how an apparently humble plant has progressed to world domination, and the consequences of it having done so. It also considers what needs to happen if, as some public health advocates would have it, we are seriously to imagine ‘a world without tobacco’. This book presents students, scholars and practitioners in anthropology, public health and social policy with unique and multiple perspectives on tobacco-human relations. Andrew Russell is Associate Professor in Anthropology at Durham University, UK, where he is a member of the Anthropology of Health Research Group. His research and teaching spans the sciences, arts and humanities, and mixes both theoretical and applied aspects. He has conducted research in Nepal, the UK and worldwide. Earlier books include The Social Basis of Medicine, which won the British Medical Association’s student textbook of the year award in 2010, and a number of edited volumes, the latest of which (co-edited with Elizabeth Rahman) is The Master Plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America. -

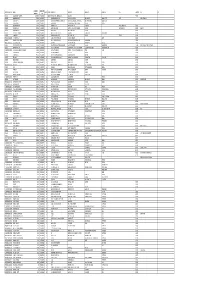

Folio / Demat Id Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Pincod Div.Amountdwno Micr Period Iepf

FOLIO / DEMAT ID NAME ADDRESS LINE 1 ADDRESS LINE 2 ADDRESS LINE 3 ADDRESS LINE 4 PINCOD DIV.AMOUNTDWNO MICR PERIOD IEPF. TR. DATE 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 10800.00 15300041 563 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 1100001100016852 R WADIWALA SECURITIES PVT LTD 9-2003-4 VISHNU PRIYA, LIMDA CHOWK MAIN ROAD SURAT 395003 22482.00 15300042 564 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 001424 BALARAMAN S N 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 18000.00 15300048 570 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 18000.00 15300052 574 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 001440 RAJI GOPALAN ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 18000.00 15300059 581 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 001765 SANTOSH MATHEW CARDIAC SURGEON TRICHUR HEART HOSPITAL TRICHUR KERALA 680001 13500.00 15300061 583 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 IN30089610488366 RAKESH P UNNIKRISHNAN KRISHNA AYYANTHOLE P O THRISSUR THRISSUR 680003 10193.00 15300066 588 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 1204760000020591 NARAYANAN K A 18/475, KUDALLUR COTTAGES CIVIL LINES ROAD THRISSUR 680004 12222.00 15300070 592 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 1100001100016565 SHAREWEALTH SECURITIES LTD XIII-789-34, DEEPEE PLAZA KOKKALAI THRISSUR THRISSUR 680021 16407.00 15300084 606 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 000316 SAMBASIVAN V.R. VAZHOOR HOUSE VALAPAD BEACH TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680567 18000.00 15300111 633 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 1204760000162413 HAMSA K S KOOTTUNGAPARAMBIL HOUSE NEAR NASEEB AUDITORIUM THALIKULAM THRISSUR 680569 15120.00 15300138 660 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 002152 KOMALAVALLY ASOKAN VELLANCHERY HOUSE PO NATTIKA BEACH THRISSUR KERALA 680572 18000.00 15300145 667 2014-15 3RD INTERIM DIVIDEND 03-MAR-22 000050 HAJI M.M.ABDUL MAJEED MUKRIAKATH HOUSE VATANAPALLY TRICHUR DIST. -

Mgl-Di219-Unpaid Share Holders List As on 31-03-2020

DIVIDEND WARRANT FOLIO-DEMAT ID NAME MICR DDNO ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 AMOUNT NO 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 192000030 680109 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 192000034 18 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 192000035 19 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 002679 NARAYANAN P S 2200.00 192000051 35 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 002976 VIJAYA RAGHAVAN 2200.00 192000056 40 KIZHAKAYIL (H) KEEZHARIYUR P O KOVILANDY KHARRUNNISSA P M 000000 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 192000057 41 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 192000060 44 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 192000063 47 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 192000064 48 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 IN30611420024859 PUSHPA DEVI JAIN 2750.00 192000075 59 A-402, JAWAHAR ENCLAVE JAWAHAR NAGAR JAIPUR 302004 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 6600.00 192000079 63 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 192000098 82 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 000493 RATHI PRATAP POYYARA 2200.00 192000101 85 10,GREENVILLA,NETAJIPALKARMARG GHATKOPAR(WEST) MUMBAI MAHARASTRA 400084 MR. PRATAP APPUNNY POYYARA 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 192000102 86 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 1201090700097429 NANASAHEB BALIRAM SONAWANE 1606.00 192000114 98 2 PALLAWI HSG SOC. -

2019 Second Quarter Results

Tokyo, July 31, 2019 2019 Second Quarter Results Highlights First half adjusted operating profit at constant FX increased 5.9% year-on-year, mainly driven by pricing gains in both the international and Japanese domestic tobacco businesses. On a reported basis, adjusted operating profit decreased 9.4% due to unfavorable currency movements. Operating profit and profit attributable to owners of the parent increased driven by a one-time compensation gain in the pharmaceutical business. FY2019 forecast for consolidated adjusted operating profit at constant FX remains unchanged. The Company announced the interim dividend of JPY 77 per share as stated in the “Business Plan 2019.” Key business segment information (January – June): International tobacco business • Adjusted operating profit at constant FX on a USD basis grew 9.3% mainly driven by solid pricing gains. On a JPY basis, adjusted operating profit decreased 13.5% due to unfavorable currency movements. • Total shipment volume grew 8.2% driven by acquisitions. Excluding these, volume was up 0.1% driven by solid GFB performance and continued market share gains, notably in Taiwan and the UK. • Expansion of Logic Compact continued with the addition of 12 new markets in the period. • Full year currency-neutral adjusted operating profit is expected to grow 10.2% year-on-year. Japanese domestic tobacco business • Adjusted operating profit increased 5.5% driven by cigarette pricing gains. • Ploom TECH+ sales expanded nationwide in June contributing to RRP sales volume growth. JT market share in the category is estimated at approximately 8%. • Ploom S will be rolled out nationwide in August 2019. • Full year adjusted operating profit is expected to decline 4.3% year-on-year. -

Investment Leading to Sustainable Growth

Corporate Information 048 Corporate Governance 058 History of the JT Group Japan Tobacco Inc. Annual Report FY2017 062 Regulation and Other Relevant Laws Year ended December 31, 2017 065 Litigation 066 Members of the Board, Audit Investment Operations & Analysis and Supervisory Board Members, leading and Executive Officers to sustainable 018 Industry Overview 067 Members of the JTI growth. 018 Tobacco Business Executive Committee 021 Pharmaceutical Business 067 Corporate Data 021 Processed Food Business 068 Investor Relations Activity 022 Review of Operations 069 Shareholder Information 022 International Tobacco Business 028 Japanese Domestic Tobacco Business 032 Global Tobacco Strategy 034 Pharmaceutical Business 038 Processed Food Business 040 Risk Factors Management 044 JT Group and Sustainability 046 Environmental, Social and 001 Performance Indicators Governance Initiatives 002 At a Glance 004 Consolidated Five-Year Financial Summary 006 Message from the Chairman and CEO Financial Information 008 CEO Business Review 010 Highlights (JT Group’s 2017) 071 Message from CFO 012 Management Principle, Strategic 072 Financial Review Framework and Resource Allocation 080 Consolidated Financial Statements 014 Business Plan 2018 086 Notes to Consolidated 015 Role and Target of Each Business Financial Statements 016 Performance Measures 139 Independent Auditor’s report 140 Glossary of Terms Management Performance Indicators Adjusted Operating Profit Dividend per Share 585.3 14 0 (JPY BN) (JPY) - 0.3% +7. 7 % Year-on-Year Change Year-on-Year Change - 0.6% Factsheets available at: Year-on-Year Change at Constant Exchange Rates https://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/ Unless the context indicates otherwise, references in this Annual Report to ‘we’, ‘us’, In addition, these forward-looking statements are necessarily dependent upon ‘our’, ‘Japan Tobacco’, ‘JT Group’ or ‘JT’ are to Japan Tobacco Inc.