A Theoretical Model to Explain the Drivers of the Internationalization Strategy of Chinese Mnes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Investors Are Funding Malign PRC Companies on Major Indices

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Spokesperson For Immediate Release FACT SHEET December 8, 2020 U.S. Investors Are Funding Malign PRC Companies on Major Indices “Under Xi Jinping, the CCP has prioritized something called ‘military-civil fusion.’ … Chinese companies and researchers must… under penalty of law – share technology with the Chinese military. The goal is to ensure that the People’s Liberation Army has military dominance. And the PLA’s core mission is to sustain the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power.” – Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, January 13, 2020 The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) threat to American national security extends into our financial markets and impacts American investors. Many major stock and bond indices developed by index providers like MSCI and FTSE include malign People’s Republic of China (PRC) companies that are listed on the Department of Commerce’s Entity List and/or the Department of Defense’s List of “Communist Chinese military companies” (CCMCs). The money flowing into these index funds – often passively, from U.S. retail investors – supports Chinese companies involved in both civilian and military production. Some of these companies produce technologies for the surveillance of civilians and repression of human rights, as is the case with Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang, China, as well as in other repressive regimes, such as Iran and Venezuela. As of December 2020, at least 24 of the 35 parent-level CCMCs had affiliates’ securities included on a major securities index. This includes at least 71 distinct affiliate-level securities issuers. -

June 2021 Trade Bulletin

June 21, 2021 Highlights of This Month’s Edition • U.S.-China Trade: In April 2021, U.S. goods exports to China were up 36.7 percent year-on-year, continuing a marked recovery from the pandemic in spite of ongoing bilateral trade tensions. • New EO Redefines and Expands Investment Restrictions: The Biden Administration has revised and expanded prohibitions on U.S. investment in Chinese companies which act contrary to U.S. national security; the list of companies subject to restrictions has grown from 44 to 59, with 18 companies removed and 33 added.* • Multilateral and Bilateral Developments: G7 joint statement highlights shared concerns about Chinese economic and human rights policies; APEC communiqué expresses common desire to improve vaccine access for Asia-Pacific economies; U.S. economic trade officials hold calls with their Chinese counterparts. • Commodity Prices Surge: China’s National Development and Reform Commission published a five-year action plan on pricing reform while regulators attempt to address spiking commodities prices. • In Focus – Wealth Management: Wall Street seizes on China’s $18.9 trillion asset management market as the Chinese government accelerates regulatory approvals to attract foreign capital and expertise. Contents U.S.-China Goods Trade Continues to Show Strong Recovery .................................................................................2 U.S. Ban on Investment in Chinese Military Companies Expands ............................................................................2 On China, Biden Administration Rallies Partners and Initiates Bilateral Dialog .......................................................5 CCP Seeks to Strengthen Commodity Price Controls ................................................................................................6 In Focus: Wall Street Seizes on China’s Burgeoning Wealth Management Sector ...................................................7 * Correction: An earlier version of the June 2021 Economics and Trade Bulletin said 17 companies were removed and 32 added. -

OEM and EMS: a Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition

OEM and EMS: A Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition A Unique Report Combining In-Depth Review of 360 OEMs’ Outsourced Electronics Assembly and Market Share Analysis of 48 Product Segments of the 100 Largest EMS Subcontractors Report Highlights Market Share by Product Segment Analysis, 2015 Automotive Communications Computers/Peripherals Consumer Electronics Industrial Medical Aerospace/Defense/Other Transportation OEM and EMS Company-Level Analysis, 2015 360 Electronic OEM Companies 100 Largest EMS Companies Outsourced/In-House Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 48 Product Segments New Venture Research Corp. A Technology Market Research Company 337 Clay St., Suite 101 info@newventureresearch .com Tel: (530) 265-2004 Fax: (530) 265-1998 OEM and EMS: A Market and Competitive Analysis - 2016 Edition Synopsis The worldwide electronics assembly market is An example can be provided for the smart phone substantial, the cost of goods sold (COGS) reached market for Apple. Whereas Apple’s EMS partners approximately $1.3 trillion dollars by 2015. The are well known, most industry participants are less market is growing but changing in terms EMS aware of other OEMs’ subcontractors which include suppliers’ market share. This report establishes the Blackberry, Lenovo, Microsoft, NEC, Sony, Toshiba, market share of the leading 100 EMS suppliers to Xiaomi, and ZTE. This report provides market share over 360 OEMs competing in 48 different markets. information on over 360 OEMs across 48 product It is the first of its kind and utilizes NVR's unique segments served by the leading 100 EMS firms. database of supplier and contractor data showing the market share of the total available EMS market. -

Sj/T 11363 – 2006

AeA-Advancing the Business of Technology English Translation For Reference Purposes Only – Binding Text is the Original Chinese Bracketed Text Indicates Additions for Clarity (not in original text) SJ Standard of the Electronics Industry of the People’s Republic of China SJ/T 11363 – 2006 Requirements for Concentration Limits for Certain Hazardous Substances in Electronic Information Products Issued: 11-06-2006 Implemented: 11-06-2006 Issued by: Ministry of Information Industry of the People’s Republic of China 1 AeA-Advancing the Business of Technology English Translation For Reference Purposes Only – Binding Text is the Original Chinese Bracketed Text Indicates Additions for Clarity (not in original text) SJ/T 11363 – 2006 Preface Appendix A of this standard is for informational purposes. This standard is subject to the jurisdiction of China Electronic Standardization Institute. The units that drew up the draft of this standard: The Fifth Research Institute of Electronics of the Ministry of Information Industry. The units that participated in drafting this standard: Please see Appendix A. Major drafters of this standard: Xiaohan Wang and Daojun Luo. 2 AeA-Advancing the Business of Technology English Translation For Reference Purposes Only – Binding Text is the Original Chinese Bracketed Text Indicates Additions for Clarity (not in original text) SJ/T 11363 – 2006 Introduction At present, many electronic information products still contain large quantities of toxic or hazardous substances or elements such as lead, mercury, cadmium, hexavalent chromium, polybrominated biphenyl, polybrominated diphenyl ether, etc., due to functional and technical needs. If these electronic information products that contain hazardous substances are disposed of improperly after they have been discarded, they will not only pollute the environment, but will also result in a waste of resources. -

TPV TECHNOLOGY LIMITED (Incorporated in Bermuda with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 903)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. TPV TECHNOLOGY LIMITED (Incorporated in Bermuda with limited liability) (Stock Code: 903) APPOINTMENT OF NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS The Board announces that Mr Zhang Dongchen and Mr Xu Guofei have been appointed as non-executive directors of the Company with effect from 30 July 2018. APPOINTMENT OF NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS The board of directors (the ‘‘Board’’) of TPV Technology Limited (the ‘‘Company’’ and together with its subsidiaries the ‘‘TPV Group’’) announces the appointment of Mr Zhang Dongchen and Mr Xu Guofei as non-executive directors of the Company with effect from 30 July 2018. Mr Zhang Dongchen, aged 55, holds a bachelor’s degree of Radio Remote Control and Telemetry from University of Electronic Science and Technology and a master’s degree of Business Administration from Xi’an Jiaotong University. He obtained a title of senior engineer (researcher level). Mr Zhang is currently the general manager and Deputy Secretary of the Leading Party Member Group of China Electronics Corporation (‘‘CEC’’). Mr Zhang had served as the assistant engineer, the engineer, the division head, the assistant to the director, the deputy director, the director and the member of the party committee of 54th Research Institute of under the Ministry of Information Technology (formerly as the 54th Research Institute of under the Ministry of Electronics Industry and now is a subsidiary under China Electronics Technology Corp), the deputy general manager and the member of the Party Leadership Group of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, the deputy general manager and Deputy Secretary of the Leading Party Member Group of CEC. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Stock Code: 903

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 REPORT ANNUAL Stock Code: 903 / 股份編號:903 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 年報 www.tpv-tech.com BUILDING RESILIENCE POWERING EXCELLENCE CORPORATE INFORMATION DIRECTORS PRINCIPAL BANKERS Executive Director Agricultural Bank of China Limited Dr Hsuan, Jason Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Chairman and Chief Executive Officer) Bank of China Limited Bank SinoPac Non-executive Directors China Construction Bank Corporation Mr Zhang Dongchen Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank Mr Xu Guofei CTBC Bank Co., Ltd. Mr Sun Jie Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Dr Li Jun JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. Ms Bi Xianghui The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited Independent Non-executive Directors INDEPENDENT AUDITOR Mr Chan Boon Teong PricewaterhouseCoopers Dr Ku Chia-Tai Certified Public Accountants Mr Wong Chi Keung COMPANY SECRETARY REGISTERED OFFICE Ms Lee Wa Ying Canon’s Court 22 Victoria Street PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR Hamilton HM 12 Estera Management (Bermuda) Limited Bermuda Canon’s Court 22 Victoria Street HONG KONG OFFICE Hamilton HM 12 Units 1208–16, 12th Floor Bermuda C-Bons International Center 108 Wai Yip Street, Kwun Tong HONG KONG BRANCH SHARE REGISTRAR Kowloon, Hong Kong Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited Shops 1712–1716 LEGAL ADVISORS 17th Floor, Hopewell Centre Appleby 183 Queen’s Road East Kirkland & Ellis International LLP Wanchai, Hong Kong SINGAPORE SHARE TRANSFER OFFICE Boardroom Corporate & Advisory Services Pte. Ltd. 50 Raffles Place #32–01 Singapore Land Tower Singapore -

Strategy Report Hong Kong Equity Research

Thursday, 3 December, 2020 China Merchants Securities (HK) Co., Ltd. Strategy Report Hong Kong Equity Research 2021 Outlook: Road towards restoration Jessie Guo, PhD +852 3189 6121 [email protected] “Lives of great men all remind us, we can make our lives sublime. Let Edith Qian, CFA +852 3189 6752 us, then, be up and doing. With a heart for any fate, still achieving, still [email protected] pursuing; learn to labour and to wait”. Harrington Zhang, PhD - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, A Psalm of Life +852 3189 6751 [email protected] Tommy Wong View on economic recovery +852 3189 6634 [email protected] The outbreak of COVID-19 sent global economic growth deep into negative Johnny Wong territory in 2020. Synchronised large-scale fiscal and monetary policies +852 3189 6357 prevented major economies from sliding into perennial recession. [email protected] According to the IMF, global GDP will contract by 4.4% in 2020 and rebound Yonghuo Liang +86 755 8290 4571 by 5.2% in 2021, but the pace of recovery will be uneven across countries. [email protected] We expect the US economy to have a relatively muted start next year, and Kevin Chen then followed by a brighter second half, while the Fed’s monetary policy will +852 3189 6125 remain abundantly accommodative throughout the entire 2021. [email protected] Felix Luo, PhD +852 3189 6288 We stay positive on China’s economic outlook, mainly driven by domestic [email protected] consumption and manufacturing investment. We expect a rather neutral Yiding Jiao, CFA fiscal and monetary policy stance. -

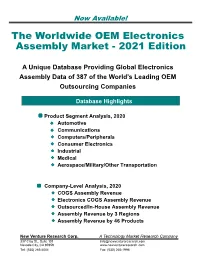

The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition

The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition A Unique Database Providing Global Electronics Assembly Data of 387 of the World’s Leading OEM Outsourcing Companies Database Highlights Product Segment Analysis, 2020 Automotive Communications Computers/Peripherals Consumer Electronics Industrial Medical Aerospace/Military/Other Transportation Company-Level Analysis, 2020 COGS Assembly Revenue Electronics COGS Assembly Revenue Outsourced/In-House Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 3 Regions Assembly Revenue by 46 Products New Venture Research Corp. A Technology Market Research Company 337 Clay St., Suite 101 [email protected] Nevada City, CA 95959 www.newventureresearch .com Tel: (408) 888-5667 Fax: (530) 265-1998 The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition Synopsis - 68 Page PP Discussion + 64 Excel Supporting Tables The worldwide electronics assembly market is The report segments the worldwide electronics substantial in size, approximately $1.4 trillion dollars assembly value into seven unique markets. in terms of cost of goods sold (COGS) as of 2020. The market has been expanding rapidly but changing Automotive in composition both in terms of outsourcing Communications partnerships with in-house manufacturing. Also, Computers/Peripherals moves are being made annually with regard to the Consumer Electronics manufacturing country of origin based on total cost. Industrial Medical Aerospace/Military/Other Transportation The following production data is given for the leading OEMs within each product/market segment. COGS Assembly Revenue Electronics COGS Assembly Revenue Outsourced/In-Housed Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 3 Regions Assembly Revenue by 46 Products New Venture Research (NVR) has followed the electronics assembly industry for over 25 years with The leading OEMs for each segment are chosen its research reports that focus on all aspects of this not only for their size, but also for their leadership industry. -

Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund Annual Report October

Annual Report | October 31, 2020 Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com. Your election to receive paper copies will apply to all the funds you hold through an intermediary or directly with Vanguard. -

RWR Pentagon List Affiliates

Publicly Traded Chinese Military Companies (and Affiliates) as Designated by the U.S. Department of Defense Published on August 31, 2020 Updated on November 12, 2020 This is a list of all the publicly traded Chinese companies that have been designated by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) as being owned or controlled by, or affiliated with, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or China’s defense industrial base. Also included are the publicly traded subsidiaries of Chinese companies designated by the DoD. The research in this report is extrapolated from RWR’s Entity Risk Tracker product, which catalogues the risk exposure of Chinese and Russian companies. It should be noted that while many of the companies listed below are directly implicated in China’s defense industrial base, several of the subsidiary companies do not have independent ties to the Chinese military and are associated, according to RWR research, only by their ownership. The companies on this list are accessible to U.S. individual and institutional investors as A Shares, H Shares, or Red Chips, and are, in some cases, included in popular indexes like the MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) Index and the FTSE All-World Index, which are used as benchmarks for exchange-traded funds (ETFs) with international exposure. These companies are sourced from the two lists of qualifying entities prepared by the Department of Defense in June and August 2020, in response to Section 1237 of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 1999. Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC)* AviChina Industry & Technology Co., Ltd. AVIC International Holdings Ltd. -

China Sanctions Update

June 15, 2021 China Sanctions Update New Executive Orders Modify Restrictions on Purchases of Securities of “Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies,” and Direct New Measures to Protect U.S. Personal Data; China Enacts New Anti- Foreign Sanctions Law SUMMARY On June 3, 2021, the Biden administration issued Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14032, which replaces the ban on transacting in securities of Chinese military companies that was established by the Trump administration in E.O. 13959. The basis for designating sanctions targets has been revised; rather than targeting “Communist Chinese Military Companies” identified by the Department of Defense under the statutory requirements of Section 1237 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1999, as amended, the revised framework gives the Treasury Department primary authority to designate companies operating in China’s defense or surveillance technology sectors, termed “Chinese Military-Industrial Complex” or “CMIC” companies, as subject to the transaction ban. In addition, a new list of covered CMIC entities has been issued which includes some, but not all, of the entities previously designated, while adding a limited number of companies not previously designated. While the previous version of these trading sanctions covered entities with a name that “closely matched” a listed name, the new prohibitions only apply to securities of entities that are specifically identified and listed. Along with the publication of E.O. 14032, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) issued important guidance regarding the scope of the restrictions. On June 9, 2021, the Biden administration issued E.O. 14034 that revoked three Trump administration E.O.s targeting Chinese software applications, including TikTok and WeChat, and, in their place, established new criteria for identifying software that potentially could threaten United States persons’ personal information and proprietary business information. -

The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition

The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition A Unique Database Providing Global Electronics Assembly Data of 387 of the World’s Leading OEM Outsourcing Companies Database Highlights Product Segment Analysis, 2020 Automotive Communications Computers/Peripherals Consumer Electronics Industrial Medical Aerospace/Military/Other Transportation Company-Level Analysis, 2020 COGS Assembly Revenue Electronics COGS Assembly Revenue Outsourced/In-House Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 3 Regions Assembly Revenue by 46 Products New Venture Research Corp. A Technology Market Research Company 337 Clay St., Suite 101 [email protected] Nevada City, CA 95959 www.newventureresearch .com Tel: (530) 265-2004 Fax: (530) 265-1998 The Worldwide OEM Electronics Assembly Market - 2021 Edition Synopsis - 68 Page PP Discussion + 64 Excel Supporting Tables The worldwide electronics assembly market is The report segments the worldwide electronics substantial in size, approximately $1.4 trillion dollars assembly value into seven unique markets. in terms of cost of goods sold (COGS) as of 2020. The market has been expanding rapidly but changing Automotive in composition both in terms of outsourcing Communications partnerships with in-house manufacturing. Also, Computers/Peripherals moves are being made annually with regard to the Consumer Electronics manufacturing country of origin based on total cost. Industrial Medical Aerospace/Military/Other Transportation The following production data is given for the leading OEMs within each product/market segment. COGS Assembly Revenue Electronics COGS Assembly Revenue Outsourced/In-Housed Assembly Revenue Assembly Revenue by 3 Regions Assembly Revenue by 46 Products New Venture Research (NVR) has followed the electronics assembly industry for over 25 years with The leading OEMs for each segment are chosen its research reports that focus on all aspects of this not only for their size, but also for their leadership industry.