Interchangeability of Ministries Between Methodists and Anglicans in Ireland: a Wider Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frontier Religion in Western Pennsylvania1 Roy H

FRONTIER RELIGION IN WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA1 ROY H. JOHNSON is wellknown that Christian missionaries have been trail blazers for ITthe path of empire on many a remote frontier. So, too, long before permanent settlements were made, emissaries of the gospel came to seek their constituents among the military outposts and scattered cabins of the trans-Allegheny region. The first leaders were subsidized and directed by eastern missionary societies, synods, associations, and conferences, but within a few decades western Pennsylvania achieved a self-sufficing stage, her log colleges and seminaries training a local ministry. Roman Catholic priests and Moravian missionaries were in the van of religious workers. In 1754 the chapel of Fort Duquesne was dedi- cated under the title of "The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin of the Beautiful River." Four years later Christian Frederick Post, a Moravian missionary, came within sight of Fort Machault, and, in 1767, his col- league David Zeisberger began a mission station "on the left bank of the Allegheny, not far from the mouth of the Tionesta."* After the conspiracy of Pontiac had been checked Presbyterian ministers came in greater numbers than other denominational workers. Before the settlers could organize to appeal for aid the Synod of New York and Philadel- phia sent traveling preachers west. During the late summer of 1766 Charles Beatty and George Duffield,Presbyterian ministers, visited Fort Bedford, Stony Creek, Laurel Hill,and Fort Pitt and passed on through 1This paper, with the title "The Religious Factor in Pioneer Life," was read at Grove City on July 15, 1932, during the historical tour under the auspices of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania and the summer session of the University of Pittsburgh. -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REV. JOHN C. BOWMER, M.A., B.O. Volume XXXV March 1966 EDITORIAL HIS year" our brethren in North America" celebrate the bi centenary of the founding of their Church; and our Society, with T so many members on that side of the Atlantic, would wish to be among the first to offer congratulations. From that night in 1766 when Philip Embury, stung into action by his cousin Barbara Heck, preached to five people in his house, or from that day when that re doubtable fighter for his Lord and his king, Captain Thomas Webb, struck fear into the hearts of a few Methodists when he appeared at one of their meetings in military uniform complete with sword, it is a far cry to the American Methodist Church of 1966. We cannot but admire the energy and enterprise which first rolled back the fron tiers and which still characterizes that progressive Church today. The birth of Methodism in North America was not painless, especi ally to Wesley, but in spite of that his name has never been any where esteemed more highly than across the Atlantic. Like a wilful child, who nevertheless knew its own mind, the Americans went their own way, but they planned better than they, or even Wesley, realized. A President of the British Conference, Dr. lames Dixon, writing in 1843 about Wesley's ideas of ecclesiastical polity, felt that if we mistake not, it is to the American Methodist Church that we are to look for the real mind and sentiments of this great man.! V/hat is fitting for one side of the Atlantic is not ipso facto fitting for the other. -

Clive D. Field, Bibliography of Methodist Historical Literature 1995. Supplement to the Proceedings of the Wesley

Supplement to the Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, May 1996 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF METHODIST HISTORICAL LITERATURE 1995 CLIVE D. FIELD, M.A., D.Phil. Information Services, The University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT 188 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BIBLIOGRAPHY OF METHODIST HISTORICAL LITERATURE, 1995 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY 1. FIELD, Clive Douglas: "Bibliography of Methodist historical literature, 1994", Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Vo!. 50, 1995-96, pp. 65-82. 2. LAZELL, David: A Gipsy Smith souvenir: a new edition of a guide to materials on or by the worldlamous preacher and singer [1860-1947], East Leake: East Leake Publishing Corner, 1995, [2] + 30 + [4]pp. 3. MANCHESTER. - John Rylands University Library of Manchester: Methodist Archives and Research Centre: Handlist of Methodist tracts and pamphlets: chronological sequence, 1801-1914; reform collections, 1803- 56; Hobill collection [arranged alphabetically by author/main entry heading], Manchester: the Library, 1993, [478]pp. 4. MANCHESTER. - John Rylands University Library of Manchester: Methodist Archives and Research Centre: Wesley Historical Society: index to the proceedings of the local branches, 1959-1994, [compiled by] Charles Jeffrey Spittal & George Nichols, Manchester: the Library, 1995, [2] + iv + 54pp. 5. MILBURN, Geoffrey Eden: "Methodist classics reconsidered, 3: H.B. Kendall's Origin and history of the Primitive Methodist Church" [London: Edwin Dalton, 1906], Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Vo!. 50, 1995-96, pp. 108-12. 6. RACK, Henry Derman: "Methodist classics reconsidered, 1: [John Smith] Simon's life of [John] Wesley" [London: Epworth Press, 1921-34], Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Vo!. 50,1995-96, pp. -

The Early Story of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Victoria

, vimmmmpm iiwumntii nmtm 9] * i f I I i *1A THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/earlystoryofweslOOblam : -s THE EARLY STORY WESLEYAN METHODIST CHURCH VICTORIA, REV. W. L. BLAMIEES, (Pbesidbnt ok the Victoria and Tasiiania Conference, 1886), AND THE REV. JOHN B. SMITH, Of TDK SAME Conference. A JUBILEE VOLUME Melbourne WESLEYAN BOOK DEPOT, LONSDALE STREET EAST, A. J. SMITH, SWANSTON STREET; W. THACKER, GEELONG: WATTS, SANDHURST. SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. ilDCCCLXXXVI. ALL RIGHTS KESERVED. GRIFFITH AND SPAVEX. CAXTOX PRINTING OFFICE. FlTZROy, MELBOURNE. PEEFACE. This volume is a contribution to the history of the Wes leyan Methodist Church in Victoria. The authors, years ago, saw the importance of preserving documents and records, which would give authentic data concerning the early times of this Church. In the year 1881, the Victoria and Tasmania Conference directed them to collect such materials, and this request was repeated by the General Conference of the Australasian Wesleyan Methodist Church. That trust has been considered a positive and sacred duty by them, and they have fulfilled it with some success, having been largely aided by numerous friends and Circuit authorities, who possessed such records. They sought also to obtain oi'al or written statements from such of the early pioneers who survive to the present time, and they are greatly indebted for such information kindly given by the Revs. W. Butters, J. Harcourt, J. C. Symons, M. Dyson, and Messrs. Witton, Beaver, Stone, the Tuckfield family, Mrs. -

Week to Two Pages

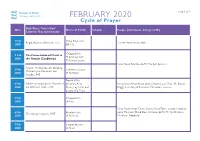

FEBRUARY 2020 Part 1 of 2 Cycle of Prayer Holy Days / Saints Day/ Date Name of Parish Schools People (Incumbent, Clergy, LLMs) Calendar Day (Lectionary) 1 Feb Shine Pinehurst Brigid, Abbess of Kildare, c.525 Curate: Revd Simon Halls 2020 (BMO) 2 Feb The Presentation of Christ in Chippenham: 2020 the Temple (Candlemas) St Andrew with Ty ther ton Lucas Vicar: Revd Rod Key, LLM: Mrs Eryl Spencer Anskar, Archbishop of Hamburg, 3 Feb Tytherton Lucas: Missionary in Denmark and 2020 St Nicholas Sweden, 865 North Wilts 4 Feb Gilbert of Sempringham, Founder of Deanery Area Area Dean: Revd. Alison Love, Deanery Lay Chair: Mr David 2020 the Gilbertine Order, 1189 Dean, Lay Chair and Briggs; Secretary & Treasurer: Mrs Hilary Greene Leadership Team 5 Feb Chippenham: 2020 St Paul Vicar: Revd Simon Dunn, Curate: Revd Tom Hunton, Associate 6 Feb Local Mininster: Revd Dave Kilmister, LLMs: Mr Neil Hutton, The Martyrs of Japan, 1597 Hardenhuish: 2020 St Nicholas Mrs Karin Needham 7 Feb Langley Burrell: 2020 St Peter FEBRUARY 2020 Part 2 of 2 Cycle of Prayer Date Anglican Cycle of Prayer Porvoo Cycle Thematic Prayer Point Lucknow (North India) The Right Revd Peter Baldev 1 Feb The homeless and those Guatemala (Central America) The Most Revd Armando Guerra 2020 who support them Soria Pray for the Anglican Church of Burundi 2 Feb The police, probation, The Most Revd Martin Blaise Nyaboho - Archbishop of Burundi & 2020 ambulance and fire services Bishop of Makamba 3 Feb Lui (South Sudan) The Most Revd Stephen Dokolo Ismail Mbalah 2020 Taiwan (The Episcopal -

Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010

The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty Doctor of Philosophy 2011 MATER DEI INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION A College of Dublin City University The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty M.A. (Spirituality) Moderator: Dr Brendan Leahy, DD Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 DECLARATION I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D. is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. ID No: 53155831 Date: ' M l 2 - 0 1 DEDICATION To my parents Betty and Donal Doherty. The very first tellers of the Easter Story to me, and always the most faithful tellers of that Story. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A special thanks to all in the Diocese of Rockville Centre in New York who gave generously of their time and experience to facilitate this research: to Msgr Bob Brennan (Vicar General), Sr Mary Alice Piil (Director of Faith Formation), Marguerite Goglia (Associate Director, Children and Youth Formation), Lee Hlavecek, Carol Tannehill, Fr Jim Mannion, Msgr Bill Hanson. Also, to Fr Neil Carlin of the Columba Community in Donegal and Derry, a prophet of the contemporary Irish Church. -

January 2005 2005 Fire Draws ‘Huge’ Support for St

New Year’s Epiphany edition edition 2005 V ol. 59, No. 5 ● January 2005 2005 Fire draws ‘huge’ support for St. John’s Thorold parish overwhelmed the diocese and beyond has been their damage in the kitchen and in the church, has said St. John’s, Thorold, insurance coverage strength after a fire damaged the church on not been determined, nor has there been an had recently been updated. by community generosity Nov. 20. estimated cost of damage. There was also “They’ve got good coverage,” she said. n the face of adversity, they’ve seen “To arrive and see smoke billowing out damage to the offices, both upper and “But it’s a very traumatic event.” Ithe face of God and it is carrying them of the church was devastating,” said The lower. St. John’s parishioners could see “the through difficult days. Reverend Canon Dr. Cathie Crawford “It’s taking a long time ... there needs to face of God” in the “huge support” from A visibly moved rector of St. John’s, Browning, rector. be inventory taken ... there is so much that parishes across the diocese and from anoth- Thorold, said the overwhelming support she The cause of the fire, which started in the goes into a claim of this magnitude.” er denomination as well. and parishioners have received from across kitchen, and left heavy smoke and water Executive Archdeacon Marion Vincett See FIRE / page 3 Niagara’s A commentary by members of the Publisher’s newspaper Advisory Board and Editor odyssey Diana Hutton he Niagara Anglican tells the Niagara story of people Tand places, good news and painful news, says the Reverend Canon Charles Stirling. -

1 the Diocese of Down and Dromore Diocesan Synod Thursday 19

1 The Diocese of Down and Dromore Diocesan Synod Thursday 19 October, 2017 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS The Rt Revd Harold Miller, Bishop of Down and Dromore Greetings to all of you, in the name of our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ. Greetings Special greetings to those who are new members of diocesan synod for this triennium, to our visitors, and especially to our brother in the Lord, Bishop Justin Badi, and his wife Mama Joyce, who have come all the way from our companionship diocese in South Sudan to be with us today. Bishop Justin will be the preacher at our Holy Communion service later this morning, and we want to assure him of our love, prayers and support for the work of the diocese of Maridi, with whom we have been linked in the Gospel since 1999. The link began when Liz and I went with Paul Clark and a team from UTV, into Maridi diocese, as people returned from being refugees, to tell their story in a television programme that Easter Day called ‘The Resurrection People’. Justin, you and your people have been in our constant prayers at this difficult time in South Sudan. I will introduce and welcome our other visitors later in the morning. We meet this morning in this wonderful parish centre in Moira, which came to be out of our own suffering here in Northern Ireland. You may not all know this, but in 1997 the IRA planted a bomb here in Moira to blow up the police station. Thankfully no-one was injured, but collateral damage included the old church hall, which had to be demolished and this parish centre rose in its place. -

PDF Download Holy Orders Kindle

HOLY ORDERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Benjamin Black | 256 pages | 06 Jun 2013 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447202189 | English | London, United Kingdom Holy Orders PDF Book Main article: Bishop Catholic Church. The consecration of a bishop takes place near the beginning of the Liturgy, since a bishop can, in addition to performing the Mystery of the Eucharist, also ordain priests and deacons. In , the minor orders were renamed "ministries", with those of lector and acolyte being kept throughout the Latin Church. Only those orders deacon , priest , bishop previously considered major orders of divine institution were retained in most of the Latin rite. Print Cite. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Elders are usually chosen at their local level, either elected by the congregation and approved by the Session, or appointed directly by the Session. Retrieved As such, she does not receive the sacrament of holy orders. In the Eastern Catholic Churches and in the Eastern Orthodox Church , married deacons may be ordained priests but may not become bishops. The deacon's liturgical ministry includes various parts of the Mass proper to the deacon, including being an ordinary minister of Holy Communion and the proper minister of the chalice when Holy Communion is administered under both kinds. A candidate for holy orders must be a baptized male who has reached the required age, has attained the appropriate academic standard, is of suitable character, and has a specific clerical position awaiting him. Who would be the human priest to whom Christ would give the power of making the God-Man present upon the altar, under the appearances of bread and wine? Once a man has been ordained, he is spiritually changed, which is the origin of the saying, "Once a priest, always a priest. -

Select Committee on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief

Select Committee on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief A Resource to assist the Church in Listening, Learning and Dialogue on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief Guide to the Conversation on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief The General Synod of the Church of Ireland Select Committee on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief This document, Guide to the Conversation on Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief, is one of three texts published by the General Synod Select Committee on Issues of Human Sexuality in the Context of Christian Belief in January 2016. It should be viewed as being in conjunction with a study programme laid out as a series of three sessions for use either by groups or individuals. Also, for ease of access, an executive summary of the Guide is available. The study of all three texts, it is hoped, will be undertaken in a prayerful spirit and the following Collect may be helpful: Most merciful God, you have created us, male and female, in your own image, and have borne the cost of all our judgments in the death of your Son; help us so to be attentive to the voices of Scripture, of humanity and of the Holy Spirit, that we may discern your will within the issues of our time, and, respectful both of conscience and of conviction, may direct our common life towards the perfection of our humanity that is in Christ alone, in whom truth and love are one. We ask this in his name. -

Church of Ireland Diocese of Down & Dromore Press

CHURCH OF IRELAND DIOCESE OF DOWN & DROMORE PRESS RELEASE: Thursday 20 June 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BISHOP HAROLD MILLER ANNOUNCES HIS RETIREMENT The Church of Ireland Bishop of Down and Dromore, the Rt Revd Harold Miller, has announced he is to retire after more than 22 years in the post. He made the announcement during his address to the Diocesan Synod on Thursday 20 June. The bishop will stand down on 30th September this year. In his address, Bishop Miller looked back with gratitude over his episcopal ministry and spoke warmly of the diocese and its people. He said, “As I look back over two decades, I truly give thanks for you, followers of Jesus Christ, in the diocese of Down and Dromore, whom I have had the privilege of getting to know and serve alongside. We have loved one another as a family, and it has been a joy to call this wonderful diocese my home.” Bishop Miller is 69 and celebrates 43 years of ordained ministry next week. He is the longest serving Bishop of Down and Dromore since Bishop Robert Knox who retired after 37 years in 1886. The bishop will give his farewell charge to the diocese at the annual Bible Week in Shankill Parish Church Lurgan, from 27-30 August. ENDS A full transcript of Bishop Miller’s Presidential Address may be found below. Contact: Annette McGrath Diocesan Communications Officer Diocese of Down and Dromore M: 07840006899 www.downanddromore.org Diocese of Down and Dromore DIOCESAN SYNOD 20 June 2019 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS The Rt Revd Harold Miller, Bishop of Down and Dromore Brothers and sisters in Christ, It has been a privilege to serve as your bishop in the diocese of Down and Dromore for just over 22 years. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 JANUARY 4/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 11/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Peter Wheatley, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Paul Williams, Bishop Jonathan Baker Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 18/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 25/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 FEBRUARY 1/2 Church of England: Diocese of Birmingham, Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Bishop Paul Colton Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Elsinore, Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel 8/2 Church in Wales: Diocese of Bangor, Bishop Andrew John Church of Ireland: Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough, Archbishop Michael Jackson 15/2 Church of England: Diocese of Worcester, Bishop John Inge, Bishop Graham Usher Church of Norway: Diocese of Hamar, Bishop Solveig Fiske 22/2 Church of Ireland: Diocese