Golden Gorgon-Medousa Artwork in Ancient Hellenic World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections October 6, 2013 - March 2, 2014

Updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 | 1:38:43 PM Last updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 Updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 | 1:38:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections October 6, 2013 - March 2, 2014 To order publicity images: Publicity images are available only for those objects accompanied by a thumbnail image below. Please email [email protected] or fax (202) 789-3044 and designate your desired images, using the “File Name” on this list. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. Links to download the digital image files will be sent via e-mail. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. Cat. No. 1A / File Name: 3514-117.jpg Statuette of Europa, 1st or early 2nd century marble height: 34.5 cm (13 9/16 in.) Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth Cat. No. 1B / File Name: 3514-118.jpg Head of Pan, 2nd century (?) marble height: 14.4 cm (5 11/16 in.) Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth Cat. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

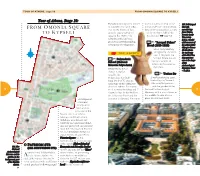

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 11, 2014 MEDIA CONTACTS: Rebecca Baldwin Nina Litoff (312) 443-3625 (312) 443-3363 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 11, 2014 MEDIA CONTACTS: Rebecca Baldwin Nina Litoff (312) 443-3625 (312) 443-3363 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO PRESENTS HEAVEN AND EARTH: ART OF BYZANTIUM FROM GREEK COLLECTIONS Over 60 Works From Greece Represent Life in the Empire that Lasted for More than a Millennium A new exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, presents more than 60 superb artworks of the Byzantine era, from the 4th to the 15th centuries. Organized by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports of Athens, Greece, with the collaboration of the Benaki Museum, Athens, and originally exhibited at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the exhibition includes major artistic holdings from Greece consisting of mosaics, sculptures, manuscripts, luxury glass, silver, personal adornments, liturgical textiles, icons, and wall paintings. About one third of the original exhibition will be presented in the Art Institute’s Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art from September 27, 2014, through February 15, 2015. For more than 1,000 years, Greece was part of the vast Byzantine Empire, established in 330 A.D. by the emperor Constantine the Great, who moved the capital of the Roman Empire east to a small town named Byzantium in modern-day Turkey. Renamed for him and transformed into Constantinople, Byzantium would come to represent an empire of splendor and power that endured for more than a millennium. Greek replaced Latin as the official language, and Greece itself was home to important centers of theology, scholarship, and artistic production—as 1 evidenced by the luxurious manuscripts displayed in the exhibition. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Ciné Paris Plaka Kidathineon 20

CINÉ PARIS PLAKA KIDATHINEON 20 UPDATED: MAY 2019 Dear Guest, Thank you for choosing Ciné Paris Plaka for your stay in Athens. You have chosen an apartment in the heart of Athens, in the old town of Plaka. In the shadow of the Acropolis and its ancient temples, hillside Plaka has a village feel, with narrow cobblestone streets lined with tiny shops selling jewelry, clothes, local ceramics and souvenirs. Sidewalk cafes and family-run taverns stay open until late, and Cine Paris (next door) shows classic movies al fresco. Nearby, the whitewashed homes of the Anafiotika neighborhood give the small enclave a Greek-island vibe. Following is a small list of recommendations and useful information for you. It is by no means an exhaustive list as there are too many places to eat, drink and sight-see than we could possibly put down. Rather, this is a list of places that we enjoy and that our guests seem to like. We find that our guests like to discover things themselves. After all is that not a great part of the joy of traveling? To discover new experiences and places. We wish you a wonderful stay, and we hope you love Athens! __________________________________________________ The site to purchase tickets online for the Acropolis and slopes, The Temple of Olympian Zeus, Kerameikos, Ancient Agora, Roman Agora, Adrians Library and Aristotle's School is here https://etickets.tap.gr/ Once you access the site in the left-hand corner there are the letters EΛ|EN; click on the EN for English. MUSEUMS THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, Dionysiou Areopagitou 15, Athens 117 42 Summer season hours (1/4 – 31/10) Winter season hours (1/11 – 31/3) Monday 8:00 - 16:00 Monday – Thursday 9:00 - 17:00 Tuesday – Sunday 8:00 – 20:00 Friday 9:00 - 22:00 Friday 8:00 a.m. -

Coverpage Final

Symbols and Objects on the Sealings from Kedesh A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Paul Lesperance IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Professor Andrea Berlin August 2010 © Paul Lesperance, 2010 Acknowledgements I have benefitted greatly from the aid and support of many people and organizations during the writing of this dissertation. I would especially like to thank my advisor, Professor Andrea Berlin, for all her help and advice at all stages of the production process as well as for suggesting the topic to me in the first place. I would also like to thank all the members of my dissertation committee (Professor Susan Herbert of the University of Michigan, as well as Professors Philip Sellew and Nita Krevans of the University of Minnesota) for all their help and support. During the writing process, I benefitted greatly from a George A. Barton fellowship to the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem in the fall of 2009. I would like to thank the fellowship committee for giving me such a wonderful and productive opportunity that helped me greatly in this endeavour as well as the staff of the Albright for their aid and support. I would also like to thank both Dr. Donald Ariel of the Israel Antiquities Authority for his aid in getting access to the material and his valuable advice in ways of looking at it and Peter Stone of the University of Cincinnati whose discussions on his work on the pottery from Kedesh helped to illuminate various curious aspects of my own. -

Conference Guide

Conference Guide Conference Venue Conference Location: Radisson Blu Athens Park Hotel 5* 5Hotel Athens” Radisson Blu Park Hotel Athens first opened its doors in 1976 on the border of the central park of Athens, Pedion Areos (Martian Field), in a safe part of the city. For 35 years the lovely park has been a wonderful host and marked the very identity of this leading deluxe hotel. Now, we thought, it is time for the hotel to host the park inside. This was the inspiration behind our recent renovation, which came to prove a virtual rebirth for Park Hotel Athens. Address: 10 Alexandras Ave. -10682 Athens-Greece Tel: +30 210 8894500 Fax: +30 210 8238420 URL: http://www.rbathenspark.com/index.php History of Athens According to tradition, Athens was governed until c.1000 B.C. by Ionian kings, who had gained suzerainty over all Attica. After the Ionian kings Athens was rigidly governed by its aristocrats through the archontate until Solon began to enact liberal reforms in 594 B.C. Solon abolished serfdom, modified the harsh laws attributed to Draco (who had governed Athens c.621 B.C.), and altered the economy and constitution to give power to all the propertied classes, thus establishing a limited democracy. His economic reforms were largely retained when Athens came under (560–511 B.C.) the rule of the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. During this period the city's economy boomed and its culture flourished. Building on the system of Solon, Cleisthenes then established a democracy for the freemen of Athens, and the city remained a democracy during most of the years of its greatness. -

Apotropaism and Liminality

Gorgo: Apotropaism and Liminality An SS/HACU Division III by Alyssa Hagen Robert Meagher, chair Spring 2007 Table of Contents List of Figures................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Gorgon and Gorgoneion.............................................................................. 5 Chapter 2: Gorgo as a Fertility Goddess....................................................................... 15 Chapter 3: Gorgo as the Guardian of Hades................................................................. 29 Chapter 4: Gorgo in Ecstatic Ritual............................................................................... 41 Chapter 5: Gorgo in the Sphere of Men......................................................................... 51 Bibliography................................................................................................................... 64 Alyssa Hagen 1 List of Figures 1.1 Attic black figure neck amphora. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu 86 AE77. Image 7 from [http://www.theoi.com/Gallery/P23.12.html].) 1.2 Mistress of Animals amulet from Ulu Burun shipwreck. (Bochum, Deutsches 9 Bergbau-Museums 104. Image from [http://minervamagazine.com/issue1704/ news.html].) 1.3 Egyptian amulet of Pataikos. (Image from Virtual Egyptian Museum 10 [http://www.virtual-egyptian-museum.org].) 1.4 Etruscan roof antefix with -

2020 Adoptions

Dimitris Arvanitakis: Head of the Publications Department Born in Zakynthos, Dimitris Arvanitakis is a graduate of the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies of the University of Athens. As a fellow of the Academy of Athens from 1995 to 1999, he conducted research for his doctoral dissertation at Istituto di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini of Venice, which was successfully defended at the Ionian University in Corfu (1999). His scientific interests span a wide range of topics: social history, history of ideas and intellectual history, history of literature and historiography, Modern Greek and Italian history, and the formation of national states. Since 2000, he has been working at the Benaki Museum and since 2006 he has been in charge of the Publications Department. In his capacity as Head of Publications, he has overseen and coordinated the publication of a great number of the Museum’s exhibition and collections catalogues and has been scientific editor of many books, including the series Benaki Museum Library. Dimitris Arvanitakis has taught in postgraduate seminars in Greece and Italy, has organized scientific conferences and has edited a number of scientific volumes. Moreover, he has published many articles in scientific volumes, journals and conference proceedings. He is a member of the Editorial Secretariat of the Greek journal Ta Istorika and the Italian journal Periptero, member of the Review Team of the journal Giornale Storico della Letteratura Italiana, Scientific Director of the Casa di Ugo Foscolo / Hugo Foscolo’s House (Zakynthos), and since 2009 he has been a Member and Coordinator of the Scientific Committee which oversees the publication of Andreas Kalvos’ Works by the Benaki Museum. -

Comic Books Vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler English Department Theses Literature and Languages Spring 4-30-2012 Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S. Latham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/english_grad Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Latham, Andrew S., "Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar" (2012). English Department Theses. Paper 1. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Literature and Languages at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Department Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMIC BOOKS VS. GREEK MYTHOLOGY: THE ULTIMATE CROSSOVER FOR THE CLASSICAL SCHOLAR by ANDREW S. LATHAM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Department of Literature and Languages Paul Streufert, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2012 Acknowledgements There are entirely too many people I have to thank for the successful completion of this thesis, and I cannot stress enough how thankful I am that these people are in my life. In no particular order, I would like to dedicate this thesis to the following people… This thesis is dedicated to my mother and father, Mark and Seba, who always believe in me, despite all evidence to the contrary.