The Gaze of the Gorgon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Gorgon-Medousa Artwork in Ancient Hellenic World

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 5, No. 1, (2019), pp. 1-14 Open Access. Online & Print DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1451898 GOLDEN GORGON-MEDOUSA ARTWORK IN ANCIENT HELLENIC WORLD Lazarou, Anna University of Peloponnese, Dept of History, Archaeology and Cultural Resources Management Palaeo Stratopedo, 24100 Kalamata, Greece ([email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 15/06/2018 Accepted: 25/07/2018 ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to highlight some characteristic examples of the golden works depicting the gorgoneio and Gorgon. These works are part of the wider chronological and geographical context of the ancient Greek world. Twenty six artifacts in total, mainly jewelry, as well as plates, discs, golden bust, coins, pendant and a vial are being examined. Their age dates back to the 6th century. B.C. until the 3rd century A.D. The discussion is about making a symbol of the deceased persist for long in the antiquity and showing the evolution of this form. The earliest forms of the Gorgo of the Archaic period depict a monster demon-like bellows, with feathers, snakes in the head, tongue protruding from the mouth and tusks. Then, in classical times, the gorgonian form appears with human characteristics, while the protruded tusks and the tongue remain. Towards Hellenistic times and until late antiquity, the gorgoneion has characteristics of a beautiful woman. Snakes are the predominant element of this gorgon, which either composes the gargoyle's hairstyle or is plundered like a jewel under its chin. This female figure with the snakes is interwoven with Gorgo- Medusa and the Perseus myth that had a wide reflection throughout the ancient times. -

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/xs25j Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

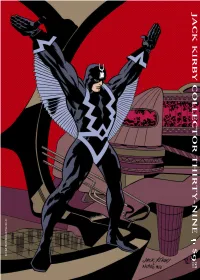

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa Isabelle George Rosett Scripps College Recommended Citation Rosett, Isabelle George, "Voices of Ancient Women: Stories and Essays on Persephone and Medusa" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1008. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1008 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICES OF ANCIENT WOMEN: STORIES AND ESSAYS ON PERSEPHONE AND MEDUSA by ISABELLE GEORGE ROSETT SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR NOVY PROFESSOR BERENFELD APRIL 21, 2017 1 2 Dedicated: To Max, Leo, and Eli, for teaching me about surviving the things that scare me and changing the things that I can’t survive. To three generations of Heuston women and my honorary sisters Krissy and Madly, for teaching me about the ways I can be strong, for valuing me exactly as I am, and for the endless excellent desserts. To my mother, for absolutely everything (but especially for fielding literally dozens of phone calls as I struggled through this thesis). To Sam, for being the voice of reason that I happily ignore, for showing up with Gatorade the day after New Year’s shenanigans, and for the tax breaks. To my father (in spite of how utterly terrible he is at carrying on a phone conversation), for the hikes and the ski days, for quoting Yeats and Blake at the dinner table, and for telling me that every single essay I’ve ever asked him to edit “looks good” even when it was a blatant lie. -

LESSON 12 the Story of Medusa and Athena

GRADE 6: MODULE 1: UNIT 2: LESSON 12 The Story of Medusa and Athena Once upon a time, a long time ago, there lived a beautiful maiden named Medusa. Medusa lived in the city of Athens in a country named Greece—and although there were many pretty girls in the city, Medusa was considered the most lovely. Unfortunately, Medusa was very proud of her beauty and thought or spoke of little else. Each day she boasted of how pretty she was, and each day her boasts became more outrageous. On and on Medusa went about her beauty to anyone and everyone who stopped long enough to hear her—until one day when she made her first visit to the Parthenon with her friends. The Parthenon was the largest temple to the goddess Athena in all the land. It was decorated with amazing sculptures and paintings. Everyone who entered was awed by the beauty of the place and couldn’t help thinking how grateful they were to Athena, goddess of wisdom, for inspiring them and for watching over their city of Athens. Everyone, that is, except Medusa. When Medusa saw the sculptures, she whispered that she would have made a much better subject for the sculptor than Athena had. When Medusa saw the artwork, she commented that the artist had done a fine job considering the goddess’s thick eyebrows—but imagine how much more wonderful the painting would be if it was of someone as delicate as Medusa. And when Medusa reached the altar, she sighed happily and said, “My, this is a beautiful temple. -

Classical Images – Greek Perseus

Classical images – Greek (birth of Pegasus from Medusa’s blood) Perseus Perseus and the birth of Perseus Running Gorgon, headless Medusa and small Perseus/ 2 Perseuses and Atehna with shield Attic bilingual white ground lekythos Black-figure pouring bowl with 3 handles th attr. Diosphos Painter, c. 500-450 BC Boiotia (Thebes), late 5 C BC New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art Boston MFA (Ac 01.8070) (1070) 1 Classical images – Greek (birth of Pegasus and Chrysaor from Medusa’s blood) Perseus The birth of Perseus and Chrysaor The birth of Perseus and Chrysaor Etruscan Athenian black-figure pyxis, 6ht C BC Munich Paris, Musée du Louvre (Ca 2588) The birth of Perseus and Chrysaor Sarcophagus from Golgoi (Cyprus) 2 Classical images – Greek (with Cetus) Perseus Corinthian black-figure amphora from Cerveteri, c. 575-550 BC Berlin, Antikensammlungen (inv F 1652) Athens, S Niarchos Collection Herakles and the Trojan Ketos Caeretan black-figure hydria; c. 530-520BC credit: www.theoi.com 3 Classical images – Greek (killing Medusa) Perseus Perseus receiving gifts of winged Perseus with hat, winged boots and kibisi over shoulder, straight sword, sandals, hat and kibisi looking away from Medusa (centaur) Eleusis, Museum Relief amphora, c. 660 BC Poaris, Musée du Louvre Perseus with Medusa’s head under his arm, with hat and winged boots Metope from Thermios, c. 630 BC 4 Athens, National Archeological Museum (13401) Classical images – Greek (killing Medusa) Perseus Perseus and the Graiai, winged Persues holding head of Medusa above Tunny fish boots, kibisis over shoulder, Stater of Mysia, Kyzikos, c. 400-330 BC stealing away with the head Boston, Museum of Fine Arts (04.1339) Attic, red-figure krater fragment Delos Museum (B7263) 5 Classical images – Greek (killing Medusa) Perseus Perseus and Polydektes with Athena at left Perseus decapitating Medusa with Athens to right Perseus averting gaze as he kills Medusa Attic red-figure bell-krater, c. -

Iconography of the Gorgons on Temple Decoration in Sicily and Western Greece

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE By Katrina Marie Heller Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright 2010 by Katrina Marie Heller All Rights Reserved ii ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE Katrina Marie Heller, B.S. University of Wisconsin - La Crosse, 2010 This paper provides a concise analysis of the Gorgon image as it has been featured on temples throughout the Greek world. The Gorgons, also known as Medusa and her two sisters, were common decorative motifs on temples beginning in the eighth century B.C. and reaching their peak of popularity in the sixth century B.C. Their image has been found to decorate various parts of the temple across Sicily, Southern Italy, Crete, and the Greek mainland. By analyzing the city in which the image was found, where on the temple the Gorgon was depicted, as well as stylistic variations, significant differences in these images were identified. While many of the Gorgon icons were used simply as decoration, others, such as those used as antefixes or in pediments may have been utilized as apotropaic devices to ward off evil. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family and friends for all of their encouragement throughout this project. A special thanks to my parents, Kathy and Gary Heller, who constantly support me in all I do. I need to thank Dr Jim Theler and Dr Christine Hippert for all of the assistance they have provided over the past year, not only for this project but also for their help and interest in my academic future. -

Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 2 | 1989 Varia Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena Ioannis Loucas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.242 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1989 Number of pages: 97-104 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Ioannis Loucas, « Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena », Kernos [Online], 2 | 1989, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.242 Kernos Kernos, 2 (1989), p. 97-104. RITUAL SURPRISE AND TERROR INANCIENT GREEK POSSESSION·DROMENA The daduch of the Eleusinian mysteries Themistokles, descendant of the great Athenian citizen of the 5th century RC'!, is honoured by a decree of 20/19 RC.2 for «he not only exhibits a manner of life worthy of the greatest honour but by the superiority of his service as daduch increases the solemnity and dignity of the cult; thereby the magnificence of the Mysteries is considered by all men to be ofmuch greater excitement (ekplexis) and to have its proper adornment»3. P. Roussel4, followed by K. Clinton5, points out the importance of excitement or surprise (in Greek : ekplexis) in the Mysteries quoting analogous passages from the Eleusinian Oration of Aristides6 and the Platonic Theology ofProclus7, both writers of the Roman times. ln Greek literature one of the earlier cases of terror connected to any cult is that of the terror-stricken priestess ofApollo coming out from the shrine of Delphes in the tragedy Eumenides8 by Aeschylus of Eleusis : Ah ! Horrors, horrors, dire to speak or see, From Loxias' chamber drive me reeling back. -

Apotropaism and Liminality

Gorgo: Apotropaism and Liminality An SS/HACU Division III by Alyssa Hagen Robert Meagher, chair Spring 2007 Table of Contents List of Figures................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Gorgon and Gorgoneion.............................................................................. 5 Chapter 2: Gorgo as a Fertility Goddess....................................................................... 15 Chapter 3: Gorgo as the Guardian of Hades................................................................. 29 Chapter 4: Gorgo in Ecstatic Ritual............................................................................... 41 Chapter 5: Gorgo in the Sphere of Men......................................................................... 51 Bibliography................................................................................................................... 64 Alyssa Hagen 1 List of Figures 1.1 Attic black figure neck amphora. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu 86 AE77. Image 7 from [http://www.theoi.com/Gallery/P23.12.html].) 1.2 Mistress of Animals amulet from Ulu Burun shipwreck. (Bochum, Deutsches 9 Bergbau-Museums 104. Image from [http://minervamagazine.com/issue1704/ news.html].) 1.3 Egyptian amulet of Pataikos. (Image from Virtual Egyptian Museum 10 [http://www.virtual-egyptian-museum.org].) 1.4 Etruscan roof antefix with