Art, Craft and Design Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospectus 2021

Driffield School 2021 & Sixth Form Prospectus Believe • Achieve Welcome to Driffield School & Sixth Form Since taking up post as Executive Principal of Driffield School & Sixth Form in April 2018, I have been delighted by the friendly and supportive nature of the students, parents and staff. The school has enormous potential and I look forward to welcoming your child to the school at such an exciting time. At Driffield School & Sixth Form, we recognise that choosing a school for your child is a crucial decision and we take our responsibilities very seriously when parents entrust their child’s education and care to us. We will do everything we can to ensure that every individual child receives the care, support and guidance they need to thrive. We are ambitious for each one of our students, sharing in their successes and seeing them leave us after seven years, able to fulfil their dreams and aspirations. We will do our utmost to help them succeed and we have high standards and expectations of all our students. All our students benefit from a broad and balanced curriculum that ensures that they experience exciting opportunities both within and outside the classroom. Our curriculum is designed to enable our students to make good progress towards their academic targets and to provide remarkable experiences that will stay with them for a lifetime. We very much hope that the information in this prospectus gives you a flavour of what we have to offer. More details are available on the school website, through regular newsletters and school round-ups. -

Make It Happen Prospectus 2020/2021 Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus

MAKE IT HAPPEN PROSPECTUS 2020/2021 WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS EXTENDED PROJECT QUALIFICATION WELCOME COURSE Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) 34 TO WYKE ENGLISH INDEX English Literature 35 “WYKE OFFERS A TRUE ‘SIXTH FORM’ EXPERIENCE WITH English Language 35 HIGH QUALITY SPECIALIST TEACHING, A UNIVERSITY STYLE BUSINESS and FINANCE MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES CAMPUS, A CULTURE THAT FOSTERS INDEPENDENCE, Accounting 22 German 36 ENCOURAGING STUDENTS TO BE THEMSELVES. Economics 22 French 37 As the largest A Level provider in Hull and East Riding, the Spanish 37 statistics are straightforward; students do very well at Wyke Business A Level 23 Sixth Form College, with our results justifying the position in Business BTEC 23 HUMANITIES the top 15% of all Sixth Form providers nationally. VISUAL ARTS History 38 In 2019, our pass rate percentage at A Level was 99.7%, with Government and Politics 38 the BTEC pass rate at 100%. This includes 315 of the top A* Fine Art 24 and A grades, 53% of the cohort achieving A*- B grades and Photography 24 Geography 39 a remarkable 82% achieving A*-C grades. Our BTEC pass rate was 100%, with 80 students achieving 3 Distinction*, Graphic Design 25 HEALTH and SOCIAL CARE the equivalent to three A*s at A Level, in comparison to 57 Art and Design Foundation Diploma 25 Health and Social Care 41 students in 2018. SCIENCES COMPUTING Our students have progressed to exceptional destinations with 10 students advancing to Oxbridge and 24 taking up Biology 26 IT and Computing 43 places on Medicine, Dentistry or Veterinary courses over the Chemistry 26 past 3 years. -

News from Across the Trust February 2020

News from across the Trust Trust training day Our annual trust training day will be held on Friday 3 April 2020. This will be held once again at Malet Lambert, taking advantage of their fantastic hall and forum area. We will be sending out further details in due course but timings will remain the same as last year. Subject CPD Teaching and Learning Library Subject Leaders across the trust have been meeting in their We have recently set up an online teaching and learning library to curriculum teams, focusing on curriculum design as well as enable all teachers to easily access academic text. The current sourcing and developing subject specific CPD. As part of these library includes: • Closing the vocabulary gap , Quigley, Alex meetings, curriculum areas are developing a trust wide shared pool • Reading reconsidered: a practical guide to rigorous literacy of subject specific resources to support teachers across the trust. instruction , Lemov, Doug These will start to be available in the summer term. • Teach like a champion 2.0: 62 techniques that put students on the path to college , Lemov, Doug Teachers have continued to collaborate across the trust and we • The Science of Learning: 77 Studies That Every Teacher have developed bespoke opportunities for teams to work together Needs to Know , Busch, Bradley • The seven myths about education , Christodoulou, Daisy on various aspects of the curriculum including new course • The writing revolution: a guide to advancing thinking through development, standardisation and moderation with the feedback writing in all subjects and grades , Hochman, Judith Wexler, from everyone being overwhelmingly positive. -

Openair@RGU the Open Access Institutional Repository at Robert

OpenAIR@RGU The Open Access Institutional Repository at Robert Gordon University http://openair.rgu.ac.uk Citation Details Citation for the version of the work held in ‘OpenAIR@RGU’: NOLAN, M. E., 2014. The content, scope and purpose of local studies collections in the libraries of further and higher education institutions in the United Kingdom. Available from OpenAIR@RGU. [online]. Available from: http://openair.rgu.ac.uk Copyright Items in ‘OpenAIR@RGU’, Robert Gordon University Open Access Institutional Repository, are protected by copyright and intellectual property law. If you believe that any material held in ‘OpenAIR@RGU’ infringes copyright, please contact [email protected] with details. The item will be removed from the repository while the claim is investigated. ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY Aberdeen Business School The Content, Scope and Purpose of Local Studies Collections in the Libraries of Further and Higher Education Institutions in the United Kingdom Marie E. Nolan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 Abstract This research examines the presence of and reasons for local studies resources in the libraries and learning centres of further and higher education institutions in the United Kingdom. The study’s aims were to investigate the content and scope of local collections in academic libraries, to examine the impact these collections have on teaching, learning and research within the institutions, and to compile an inventory of local resources in college and university libraries. Using an approach combining basic- and applied research, the study represents the most comprehensive investigation of local resources in academic libraries so far. -

180109 Schools Statement

Statement by West Sussex MPs West Sussex MPs lobbied hard for the introduction of a National Funding Formula, and the extra £28 million for West Sussex schools has gone a considerable way towards making funding fairer. Our secondary schools will receive up to 12 per cent more funding when the Formula is fully implemented. We recognise that there is further to go, and that schools are facing cost pressures, and we are particularly concerned about the funding of primary schools once transitional help has passed, the sustainability of small rural primary schools and the challenges for schools in less well-off urban areas. We have been in constant discussions with our local schools and West Sussex County Council about these issues. Our schools should be funded on the same basis as those in their peer group across England, although we must be wary of crude comparisons since everyone is agreed that schools in very deprived inner city areas will always have additional needs. This issue remains a high priority for West Sussex MPs, and we will continue to stand up strongly for our local schools, including through representations to the new Education Secretary and the Chancellor. However, this is not just about funding. We are also very concerned about standards which in too many West Sussex schools have not been good enough, and we want to hear more about how improvements will be made. Notes 1. Overall impact of NFF on West Sussex The National Funding Formula delivers on full implementation (on the basis of current pupil numbers) an additional £28 million to West Sussex. -

Outreach & Partnerships

OUTREACH & PARTNERSHIPS Strengthening Forest through collaboration Where People Grow 2019 / 2020 2 Contents Introductions 4-5 Community 29 International 52 Our Partnership: LAE 6 Community Action 30 Economic Impact 53 Hackney Empire 7 Covid-19 C.A. 36 The Future 54 STEAM 8 Staff Volunteering 39 British Science Week 10 Local Education 41 Humanities & Literacy 24 Governance 46 Careers 26 The Arts 28 Charity 48 Whole School 49 Senior School 50 Prep School 51 3 Warden’s Introduction Like Forest, almost every independent school has In the present crisis, with independent schools formed partnerships with schools in the maintained adjusting their models to ensure long-term viability sector. Rightly so, because sharing resources and in the face of economic crisis, there is a danger that expertise beyond those who can afford fees is part outreach work will be the first victim of reduced of Forest’s character. We are at the stage of outreach budgets. Hopefully, not at Forest where we remain development where there is a growing understanding of the view that there has never been a more of what partnerships should look like, how they important time to live your values, and show a firm work best to mutual benefit, and how their impact understanding of what outreach work does for your can be measured, reported and built upon. We are own school. therefore becoming more diligent in recording and measuring what we have done for the public benefit, To close the gates and become an insular institution rather than expecting everyone to take on trust that would do our pupils a disservice and would be a we are committed to the causes of social mobility. -

Routes Into Leisure & Tourism

Routes into Leisure & Tourism (including Hospitality, Catering and Sport) www.ahkandm.ac.uk Introduction Leisure, tourism and catering industries are booming. Are you aware of the current career opportunities within these industries? This booklet tells you about the courses that are available in Kent and Medway to help you get qualified for a career in these fields. You can choose to do a short course to boost your Many of the courses on offer are current prospects or take a longer course to flexible and family friendly, and become qualified in something new. Before students often take a year or two out you know it, you could become a qualified before taking a second, or even a chef, a professional football coach or a tour third course. Of course, this means manager! you’re always improving your career and pay prospects. Once you’ve Training in these industries will not only prepare read through the booklet and have you for an exciting job, but will also teach you an idea what you would like to do, valuable “soft skills” that you can use in any take a look at the progression maps industry. Being able to interact well with clients, at the back; Travel and Tourism, effectively manage your staff or business in Hospitality and Catering and Sport addition to multi-tasking and working in teams each have their own map. These are all skills you can develop now and carry will tell you the courses that are with you throughout your career. available and where. Looking at this map will also help you see what type of employment or further courses they can lead onto. -

The New and the Old: the University of Kent at Canterbury” Krishan Kumar

1 For: Jill Pellew and Miles Taylor (eds.), The Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of the 1960s “The New and the Old: The University of Kent at Canterbury” Krishan Kumar Foundations and New Formations1 It all began with a name. A new university was to be founded in the county of Kent.2 Where to put it? In the end, the overwhelming preference was for the ancient cathedral city of Canterbury. But that choice of site was by no means uncontested. There was no lack of alternatives. Ashford, Dover, and Folkestone all put in bids. The Isle of Thanet in East Kent was for some time a strong contender, and its large seaside town of Margate, with its many holiday homes, undoubtedly seemed a better prospect than Canterbury for the provision of student accommodation, in the early years at least. Ramsgate too, with a large disused airport, was another strongly- urged site in Thanet. But as far back as 1947, Canterbury had been proposed as the site of a new university in the county. That proposal got nowhere, but the idea that Canterbury – rather than say Maidstone, the county capital, or anywhere else in Kent – should be the place where and when a new university was founded had caught the imagination of many in the county. Thanet might, from a practical point of view, have been the better site. But it lacked the cultural significance and the wealth of historical associations of the city of Canterbury. Moreover the University of Thanet, or the University of Margate or Ramsgate, did not have quite the same ring to it as the University of Kent or the University of Canterbury.3 That at least was the strong opinion of the two bodies that brought the University into being, the Steering Committee of Kent County Council and the group of the great and the good in the county that came together as “Sponsors of the University of Kent”- most prominent among them being its chairman, Lord Cornwallis, Lord Lieutenant of Kent and former chairman of Kent County Council.4 2 Canterbury having been chosen as the site, what to call the new foundation? That proved trickier. -

Secondary School Page 0

APPLY ONLINE for September 2021 at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions by 31 October 2020 Admission to Secondary School Page 0 APPLY ONLINE for September 2021 at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions by 31 October 2020 Information for Parents Admission to Secondary School – September 2021 How to apply for a school place – Important action required Foreword by the Director of Education and Skills Applying for a place at secondary school is an exciting and important time for children and their parents. The time has now come for you to take that important step and apply for your child’s secondary school place for September 2021. To make the process as easy as possible, West Sussex County Council encourages you to apply using the online application system at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions. All the information you need to help you through the process of applying for a secondary school place is in this booklet. Before completing your application, please take the time to read this important information. The frequently asked questions pages and the admission arrangements for schools may help you decide on the best secondary schools for your child. We recognise that this year has been an unusual year with schools taking additional precautions to ensure safety for both staff and pupils during the current pandemic. However, many schools are making arrangements for prospective parents to better understand the school and to determine whether the school is the right fit for your child. Arrangements for visiting schools or for finding more out about the school may be organised differently to the way schools have managed this previously. -

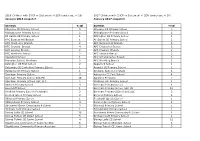

2016 Children with EHCP Or Statement of SEN (Under Age Of

2016 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) 2017 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) January 2016 snapshot January 2017 snapshot SCHOOL Total SCHOOL Total Albourne CE Primary School 5 Albourne CE Primary School 3 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 All Saints CE Primary School 1 Aldrington CE Primary School 1 APC Burgess Hill Branch 1 All Saints CE Primary School 2 APC Chichester Branch 2 APC Burgess Hill Branch 5 APC Crawley Branch 4 APC Chichester Branch 3 APC Lancing Branch, 2 APC Crawley Branch 1 APC Worthing Branch 2 APC Lancing Branch 3 Appleford School 1 APC Littlehampton Branch 1 Arunside School, Horsham 3 APC Worthing Branch 1 Ashington CE First School 2 Appleford School 1 Balcombe CE Controlled Primary School 1 Arundel CE Primary School 1 Baldwins Hill Primary School 1 Arunside School, Horsham 4 Barnham Primary School 3 Ashington CE First School 4 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Awaiting Provision 7 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 2 Baldwins Hill Primary School 4 Bartons Primary School 4 Barnham Primary School 4 Beechcliff School 1 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Benfield Primary School (Portslade) 2 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 3 Bersted Green Primary School 2 Bartons Primary School 4 Bilingual Primary School 1 Beechcliff Special School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 4 Bersted Green Primary School 3 Birchwood Grove Community P School 3 Bilingual Primary School 1 Birdham CofE Primary School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 2 Bishop Luffa CE School 10 Birchwood Grove -

Friends Newsletter 2019 Foreword from the Headteacher, Ms Elizabeth Kitcatt

Friends Newsletter 2019 Foreword from the Headteacher, Ms Elizabeth Kitcatt It has been a busy year here at Camden School for Girls, as always. Our new priority is to improve the grounds, and we now have green screens and wonderful whirling seats for students to enjoy! Our school performed outstandingly well in the DFE Performance tables, as I’m sure you will be aware, and it is now in the top 3% of schools nationally in terms of the progress our students make while they are with us. We continue to attract remarkable speakers to the school and in particular, to the Sixth Form assemblies, and you will find accounts of some of their presentations in this newsletter. You will see that Camden students continue to raise money for charity, make exceptional music and produce compelling artwork. We said goodbye to Geoffrey Fallows, very sadly, but found it a pleasure to re-visit his contribution and remember his cheerful leadership of the school. I hope you enjoy this sample of life here at CSG. Elizabeth Kitcatt Headteacher, Camden School for Girls August brought some outstanding exam results. GCSE results were exceptional. 91% of all results across all subjects were grades 9-4. 90% achieved grade 9-4 (standard pass) in both English and mathematics. 34 students achieved 9-7 grades in eight or more GCSE subjects. Our students worked especially hard to achieve top grades, not simply to achieve a GCSE result. 25 students celebrate We were delighted with the A level results achieved as well with our Cambridge, Oxford and out-performing students nationally by a very significant margin. -

Frederick Bremer School Inspection Report

Frederick Bremer School Inspection report Unique Reference Number 103094 Local Authority Waltham Forest Inspection number 333038 Inspection dates 11–12 June 2009 Reporting inspector Glynis Bradley-Peat This inspection of the school was carried out under section 5 of the Education Act 2005. Type of school Comprehensive School category Community Age range of pupils 11–16 Gender of pupils Mixed Number on roll School (total) 907 Appropriate authority The governing body Chair Mr Malcolm Howard Headteacher Ms Ruth Woodward Date of previous school inspection Not previously inspected School address Siddeley Road Walthamstow London E17 4EY Telephone number 020 8498 3340 Fax number 020 8523 5323 Age group 11–16 Inspection dates 11–12 June 2009 Inspection number 333038 Inspection Report: Frederick Bremer School, 11–12 June 2009 2 of 11 . © Crown copyright 2009 Website: www.ofsted.gov.uk This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that the information quoted is reproduced without adaptation and the source and date of publication are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the Education Act 2005, the school must provide a copy of this report free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Inspection Report: Frederick Bremer School, 11–12 June 2009 3 of 11 Introduction The inspection was carried out by four Additional Inspectors. Description of the school The school is of average size and was established in September 2008 as a result of the amalgamation of Aveling Park School and Warwick Boys School.