State Adoption of Transformative Technology: Early Railroad Adoption in China and Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2014 © 2013 William M. Coleman, IV All rights reserved Abstract Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV This dissertation analyzes the process of state building by Qing imperial representatives and Republican state officials in Batang, a predominantly ethnic Tibetan region located in southwestern Sichuan Province. Utilizing Chinese provincial and national level archival materials and Tibetan language works, as well as French and American missionary records and publications, it explores how Chinese state expansion evolved in response to local power and has three primary arguments. First, by the mid-nineteenth century, Batang had developed an identifiable structure of local governance in which native chieftains, monastic leaders, and imperial officials shared power and successfully fostered peace in the region for over a century. Second, the arrival of French missionaries in Batang precipitated a gradual expansion of imperial authority in the region, culminating in radical Qing military intervention that permanently altered local understandings of power. While short-lived, centrally-mandated reforms initiated soon thereafter further integrated Batang into the Qing Empire, thereby -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Special Issue Taiwan and Ireland In

TAIWAN IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is the first scholarly journal based outside Taiwan to contextualize processes of modernization and globalization through interdisciplinary studies of significant issues that use Taiwan as a point of comparison. The primary aim of the Journal is to promote grounded, critical, and contextualized analysis in English of economic, political, societal, and environmental change from a cultural perspective, while locating modern Taiwan in its Asian and global contexts. The history and position of Taiwan make it a particularly interesting location from which to examine the dynamics and interactions of our globalizing world. In addition, the Journal seeks to use the study of Taiwan as a fulcrum for discussing theoretical and methodological questions pertinent not only to the study of Taiwan but to the study of cultures and societies more generally. Thereby the rationale of Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is to act as a forum and catalyst for the development of new theoretical and methodological perspectives generated via critical scrutiny of the particular experience of Taiwan in an increasingly unstable and fragmented world. Editor-in-chief Stephan Feuchtwang (London School of Economics, UK) Editor Fang-Long Shih (London School of Economics, UK) Managing Editor R.E. Bartholomew (LSE Taiwan Research Programme) Editorial Board Chris Berry (Film and Television Studies, Goldsmiths College, UK) Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao (Sociology and Civil Society, Academia Sinica, Taiwan) Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang (Comparative Literature, University of Texas, USA) Kent Deng (Economic History, London School of Economics, UK) Bernhard Fuehrer (Sinology and Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, UK) Mark Harrison (Asian Languages and Studies, University of Tasmania, Australia) Bob Jessop (Political Sociology, Lancaster University, UK) Paul R. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Translation Skills of Sichuan Cuisine in the Context of Globe Business Du Weihua1,A, Hu Zhongli2,B*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 554 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2021) Translation Skills of Sichuan Cuisine in the Context of Globe Business Du Weihua1,a, Hu Zhongli2,b* 1 German Dept. Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China 2 German Dept. Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China a [email protected] b* Corresponding author, [email protected] ABSTRACT Chinese food has its own historical heritage, and Overseas Chinese miss it, and foreigners are more and more accepting of Chinese food. Sichuan cuisine is one of the eight major cuisines in China. At present, there are some good researches on the translation of the names of Sichuan cuisine. This paper investigates ten Chinese restaurants in Britain and the United States, and two restaurants in Switzerland. It analyzes the common translation methods of Sichuan cuisine, and then comes to the conclusion that transliteration plus free translation is the best way to translate Sichuan cuisine, and the translation method of dish names with high differentiation and easy memory is used, which is convenient for Chinese dishes to go out in the context of globe business. Keywords: Sichuan cuisine, name, translation, skills 1. INTRODUCTION from almost all major cuisines, restaurant specialities and their cooking methods, and even Western food, entered Sichuan cuisine is one of the eight major cuisines in Sichuan. Not only did many famous Sichuan restaurants China and is renowned in China and abroad. It can be and chefs emerge, such as Lan Guangjian of Ronglan roughly divided into three branches, namely the Upper Paradise and Luo Guorong of Yi Zhi Shi, but a number of River Gang (Western Sichuan), the Small River Gang modern Sichuan masters emerged, and a relatively fixed (Southern Sichuan) and the Lower River Gang (Eastern division of labour emerged. -

Ralff Jiang Chinese Chef

Ralff Jiang Chinese Chef Born in the Chinese city of Dalian, Ralff was inspired to take up cooking, while helping his father manage their family restaurant with a decade’s experience; he plates the best of Cantonese and Szechwan Cuisine with a Yin and Yang appeal Noble House Signature Dish PEKING DUCK Peking Duck is a famous duck dish from Beijing that has been prepared since the imperial era. The dish is prized for its thin crisp skin, which is sliced in front of the diners by the Chef. Ducks bred specially for the dish are seasoned before being roasted in a closed or hung oven. The crisp skin is eaten with leeks, cucumber and Hoisin sauce with homemade pancakes rolled around the fillings. Half Peking Duck (6 rolls) L.E. 1450 ++ Whole Peking Duck (12 rolls) L.E. 2850 ++ Healthy Cuisine Created using fresh and nutritionally balanced ingredients, Healthy Cuisine dishes contribute to optimal health and wellness (v) Vegetarian dish Dear Guest, should you have special dietary requirements, allergies, or may wish to know about the ingredients used, please ask a member of the staff Kindly note that in order to guarantee the quality of the dishes, there are no other food items served in this outlet other than listed on this menu All prices are quoted in Egyptian Pound (LE) and are subject to applicable fees and taxes as well as 12% service charge Our dim sum chef Zhang xiang guo, Have more than 10 years 5 stars hotel dim sum experience DIM SUM Steamed dim and boiled sum Crystal prawns dumpling 水晶虾饺 160 Chicken and prawn shao mai 鸡肉鲜虾烧麦 140 Steamed -

The Circulation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Research Spring 5-17-2019 A War of Words: The irC culation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions Jordan Weinstock Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Weinstock, Jordan, "A War of Words: The irC culation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions" (2019). Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses. 15. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/undergrad_etd/15 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Papers / Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A War of Words: The Circulation and Interpretation of Taiping Depositions By Jordan Weinstock A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Honors in History In the College of Arts and Sciences Washington University Advisor: Steven B. Miles April 1 2019 © Copyright by Jordan Weinstock, 2019. All rights reserved. Abstract: On November 18, 1864, the death knell of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was rung. Hong Tiangui Fu had been killed. Hong, divine leader of the once nascent kingdom and son of the Heavenly Kingdom’s founder, was asked to confess before his execution, making him one of the last figures to speak directly on behalf of the Qing’s most formidable opposition. The movement Hong had inherited was couched in anti-Manchu sentiment, pseudo-Marxist thought, and a distinct, unorthodox, Christian vision. -

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan

Bannerman and Townsman: Ethnic Tension in Nineteenth-Century Jiangnan Mark Elliott Late Imperial China, Volume 11, Number 1, June 1990, pp. 36-74 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/late.1990.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/late/summary/v011/11.1.elliott.html Access Provided by Harvard University at 02/16/13 5:36PM GMT Vol. 11, No. 1 Late Imperial ChinaJune 1990 BANNERMAN AND TOWNSMAN: ETHNIC TENSION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY JIANGNAN* Mark Elliott Introduction Anyone lucky enough on the morning of July 21, 1842, to escape the twenty-foot high, four-mile long walls surrounding the city of Zhenjiang would have beheld a depressing spectacle: the fall of the city to foreign invaders. Standing on a hill, looking northward across the city toward the Yangzi, he might have decried the masts of more than seventy British ships anchored in a thick nest on the river, or perhaps have noticed the strange shapes of the four armored steamships that, contrary to expecta- tions, had successfully penetrated the treacherous lower stretches of China's main waterway. Might have seen this, indeed, except that his view most likely would have been screened by the black clouds of smoke swirling up from one, then two, then three of the city's five gates, as fire spread to the guardtowers atop them. His ears dinned by the report of rifle and musket fire and the roar of cannon and rockets, he would scarcely have heard the sounds of panic as townsmen, including his own relatives and friends, screamed to be allowed to leave the city, whose gates had been held shut since the week before by order of the commander of * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Manchu Studies (Manzokushi kenkyùkai) at Meiji University, Tokyo, in November 1988. -

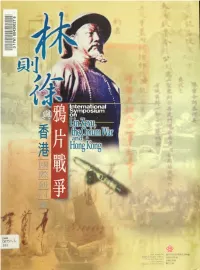

Internatioanl Symposium on Lin Zexu, the Opium War and Hong Kong = Lin Zexu, Ya Pian Zhan Zheng Yu Xianggang Guo Ji Yan Tao

c * Jointly organized by ft W (# Hong Kong Museum of Hislory. Pro\ isional Urban Council Hit^fr Lin Ze.\u Koundalion Association of Chinese Histonans M -f: ' I International Symposium on Lin Zexu, the Opium War and Hong Kong ate: 18-19.12.98 = 'Lin Zexu and the Opium War " Exhibitii Date of Opening: 1 ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( 1' ( Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre 1 Spadioa Crescent, Rm. Ill • Toronto, Canada • M5S 1A1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Multicultural Canada; University of Toronto Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/linzexuyapianzhaOOhong ) ) #^ List of Parti cipants ( ( Listed in alphabetical order) Mainland: 1. Prof. Dai Xueji (Institute of Social Sciences, Fujian) 2. Prof. Deng Kaisong (Office of Hong Kong and Macau History, Institute of Social Sciences, Guangdong 3. Prof. Hao Guiyuan (Institute of World History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 4. M Prof. Huang Shunli (Department of History, University of Xiamen) 5. Prof. Jiang Dachun (Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 6. Prof. Lai Xinxia (Local Document Research Institute, Nankai University) 7. I Prof. Li Hongsheng (University of Social Sciences, Guangdong I History Society, Guangdong 8. Prof. Lin Qingyuan (Department of History, Fujian Normal University) 9. Prof. Lin Zidong (Federation of Social Sciences, Fujian) 10. Prof. Ling Qing (Lin Zexu Foundation) 11. Prof. Liu Shuyong (Institute of Modem History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) 12. Prof. Wang Rufeng (Department of History, The People's University of China) 13. Prof. Xiao Zhizhi (Academy of History and Culture, University of Wuhan) 14. Jl Prof. Yang Guozhen (Institute of Historical Research, University of Xiamen) 15. -

Developmentalism in Late Qing China, –

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX DEVELOPMENTALISM IN LATE QING CHINA, – * JONATHAN CHAPPELL Independent scholar ABSTRACT. This article explores the changing historical referents that Qing officials used in arguing for the extension of direct governance to the empire’s frontier regions from the sto the s. In the s, Shen Baozhen and Zuo Zongtang made the case for a change of governance on Taiwan and in Xinjiang respectively by reference to past Chinese frontier management. However, in the first decade of the twentieth century Cen Chunxuan and Yao Xiguang both referred to the European past, and specifically the history of European colonialism, to argue for reform of frontier policy in Mongolia. I argue that this shift was a result of both the empire’s altered political circum- stances and a growing belief in the inevitability of an evolutionary fate which awaited nomadic peoples, who were destined to be colonized. Yet this was not a case of Chinese thinkers simply adopting European ideas and perspectives wholesale. The adoption of European historical referents was entangled with Han Chinese perceptions of Mongolian populations which had been carefully culti- vated by the Manchu Qing state. -

Naval Warfare and the Refraction of China's Self-Strengthening Reforms

Modern Asian Studies 38, 2 (2004), pp. 283–326. 2004 Cambridge University Press DOI:10.1017/S0026749X04001088 Printed in the United Kingdom Naval Warfare and the Refraction of China’s Self-Strengthening Reforms into Scientific and Technological Failure, 1865–18951 BENJAMIN A. ELMAN Princeton University In the 1950s and 1960s, Chinese, Western, and Japanese scholarship debated the success or failure of the government schools and regional arsenals established between 1865 and 1895 to reform Qing China (1644–1911). For example, Quan Hansheng contended in 1954 that the Qing failure to industrialize after the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) was the major reason why China lacked modern weapons during the Sino-Japanese War.2 This position has been built on in recent reassessments of the ‘Foreign Affairs Movement’ (Yangwu yundong) and Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 ( Jiawu zhanzheng) by Chinese scholars. They argue, with some dissent, that the inadequacies of the late Qing Chinese navy and army were due to poor armaments, insufficient training, lack of leadership, vested interests, lack of funding, and low morale. In aggregate, these factors are thought to demonstrate the inadequacies of the ‘Self- Strengthening era’ and its industrial programs.3 1 An earlier version was presented at the conference ‘The Disunity of Chinese Science,’ organized by Roger Hart (University of Texas, Austin), sponsored by the History of Science Program at the University of Chicago, May 10–12, 2002.My thanks to an anonymous reader who suggested parts to expand and who also dir- ected me to important recent work on the topic. 2 Quan Hansheng, ‘Jiawu zhanzhen yiqian de Zhongguo gongyehua yundong,’ Lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan 25, 1 (1954): 77–8.