Johnson, Harry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Paper No. 21 / January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Community Cohesion in Liberia A Post-War Rapid Social Assessment Paul Richards Steven Archibald Beverlee Bruce Public Disclosure Authorized Watta Modad Edward Mulbah Tornorlah Varpilah James Vincent Public Disclosure Authorized Summary Findings At the core of Liberia’s conflict lies a class of Promoting CDD activities based on generalized marginal young people who currently lack faith in assumptions about ‘community participation’ and any kind of institutions. They consider that family, ‘consensus’ risks empowering certain groups over marriage, education, markets and the administration others. CDD processes should support, as far as of justice have all failed them. Many have preferred practicable, community-led definitions of co- to take their chances with various militia groups. operation and management structures. It must also be Successful peacebuilding, and reconstruction through recognized that some community-based ways of community empowerment will, to a large extent, organizing serve to empower particular groups over depend upon the dismantling of these institutionally others, and that external agency/NGO-initiated embedded distinctions between citizens and subjects. structures typically do likewise. A genuinely inclusive, appropriately targeted community-driven development (CDD) process There is a danger in seeing CDD activities only in could play a crucial role in shaping a different kind of technical terms, e.g., as an exercise in simply society, but only if it incorporates marginalized and providing infrastructure, or in transferring socially-excluded groups in the rebuilding process. international procedures for participatory development. To avoid this, communities themselves The rapid social assessment (RSA) reveals that the need to engage in analysis of different forms of co- assumptions of social cohesion, community operation and solidarity to create social capital that participation and consensus underpinning some CDD encourages cohesion. -

Culture and Customs of Liberia Liberia

Culture and Customs of Liberia Liberia. Cartography by Bookcomp. Culture and Customs of Liberia 4 AYODEJI OLUKOJU Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olukoju, Ayodeji. Culture and customs of Liberia / Ayodeji Olukoju. p. cm. — (Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–33291–6 (alk. paper) 1. Liberia—Social life and customs. 2. Liberia—Civilization. I. Title. II. Series. DT629.O45 2006 966.62—dc22 2005030569 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2006 by Ayodeji Olukoju All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2005030569 ISBN 0–313–33291–6 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2006 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Copyright Acknowledgments The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to reprint the following: Song lyrics from the Liberian Studies Journal, “Categories of Traditional Liberian Songs” by Moore and “Bai T. Moore’s Poetry…” by Ofri-Scheps. Reprinted with permission of Liberian -

Religious Leaders, Peacemaking, and the First Liberian Civil War August 2013

Religion and Conflict Case Study Series Liberia: Religious Leaders, Peacemaking, and the First Liberian Civil War August 2013 © Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/resources/classroom 4 Abstract 5 This case study examines the ultimately unsuccessful attempt of Liberian re- ligious leaders to intervene in their country’s First Civil War (1989-1996) 6 between the government and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) with the goal of establishing peace. The core text of the case study explores 9 four essential questions: What are the causes of conflict in Liberia? How did domestic religious leaders promote peace? How important were international religious and political forces? What factors explain the failure of religion- inspired peacebuilding? Complementing the core text are a timeline of key events, a guide to relevant religious organizations, and a helpful list of further readings. 12 About this Case Study 13 This case study was crafted by George Kieh under the editorial direction of Eric Patterson, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Government and associate director of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. This case study was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Founda- tion and the Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs. 2 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — LIBERIA Contents Introduction 4 Historical Background 5 Domestic Factors 6 Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors 9 International Factors 10 Resources Key Events 12 Religious Organizations 13 Further Reading 14 Discussion Questions 15 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — LIBERIA 3 Introduction On December 24, 1989, a group of rebels operating un- decided to intervene in the war as peacemakers through a der the umbrella of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia strategy of mediation and negotiation. -

Report Burma

April 2000 n°290/2 International Federation of Human Rights Leagues Report Special Issue The Newletter of the FIDH International Mission of Inquiry Burma repression, discrimination and ethnic cleansing in Arakan I. Arakan A. Presentation of Arakan - A buffer State B. Historical background of the Muslim presence in Arakan C. Administration organisation, repressive forces and armed resistance II. The forced return and the reinstallation of the Rohingyas: hypocrisy and constraints A. The conditions of return from Bangladesh after the 1991-92 exodus B. Resettlement and reintegration III. Repression, discrimination and exclusion in Arakan A. The specificity of the repression against the Rohingyas B. The Arakanese: an exploitation with no way out IV. A new exodus A. The years 1996 and 1997 B. The current exodus Conclusion Repression, discrimination and ethnic cleansing in Arakan In memory of Yvette Pierpaoli P AGE 2 Repression, discrimination and ethnic cleansing in Arakan Summary Introduction................................................................................................................................... p.4 I. Arakan ....................................................................................................................................... p.5 A. Presentation of Arakan - A buffer State............................................................................................... p.5 B. Historical background of the Muslim presence in Arakan......................................................................p.5 -

Some Meanings of the Islamic Call to Prayer

Some Meanings of the Islamic Call to Prayer: A Combined Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Some Turkish Narratives Eve Mcpherson, Sandra Mcpherson, Roger Bouchard, Robert Heath Meeks To cite this version: Eve Mcpherson, Sandra Mcpherson, Roger Bouchard, Robert Heath Meeks. Some Meanings of the Islamic Call to Prayer: A Combined Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Some Turkish Narratives. Narrative Matters 2014: Narrative Knowing/ Récit et Savoir, Sylvie Patron, Brian Schiff, Jun 2014, Paris, France. hal-01111087 HAL Id: hal-01111087 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01111087 Submitted on 2 Feb 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Some Meanings of the Islamic Call to Prayer: A Combined Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Some Turkish Narratives Eve A. McPherson, PhD Assistant Professor of Music Kent State University at Trumbull Sandra B. McPherson, PhD Emerita, Department of Psychology The Fielding Graduate University Roger Bouchard, MSc, MA Graduate Research Assistant The Fielding Graduate University Robert Heath Meeks, MS Graduate Research Assistant The Fielding Graduate University The origin story of the call to prayer, circa 620 CE: In the days of the Prophet Mohammed, it was deemed important to have a way to call the faithful to prayer. -

A Strategy to Engage Islamic Youth and Young Adults in Grand Cape

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Project Documents Graduate Research 2014 A Strategy to Engage Islamic Youth and Young Adults in Grand Cape Mount County, Liberia Matthew .F Kamara Andrews University This research is a product of the graduate program in Doctor of Ministry DMin at Andrews University. Find out more about the program. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Kamara, Matthew F., "A Strategy to Engage Islamic Youth and Young Adults in Grand Cape Mount County, Liberia" (2014). Project Documents. 64. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/64 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Project Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO ENGAGE ISLAMIC YOUTH AND YOUNG ADULTS IN GRAND CAPE MOUNT COUNTY, LIBERIA By Matthew Foday Kamara Advisers: Bruce C. Moyer Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Project Document Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO ENGAGE ISLAMIC YOUTH AND YOUNG ADULTS IN GRAND CAPE MOUNT COUNTY, LIBERIA Name of Researcher: Matthew F. Kamara Name and degree of faculty advisers: Bruce C. -

Bibliography on Islam in Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Schrijver, P

Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Schrijver, P. Citation Schrijver, P. (2006). Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12922 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12922 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa African Studies Centre Research Report 82 / 2006 Bibliography on Islam in contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa Paul Schrijver Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Tel. +31 (0)71-527 33 72 Fax: +31 (0)71-527 33 44 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ascleiden.nl Printed by PrintPartners Ipskamp BV, Enschede ISBN-10: 90 5448 067 x ISBN-13: 978 90 5448 067 9 © African Studies Centre, Leiden, 2006 Contents Preface vii I AFRICA (GENERAL) 1 II WEST AFRICA 21 West Africa (General) 21 Benin 32 Burkina Faso 32 Côte d'Ivoire 36 Gambia 39 Ghana 39 Guinea 43 Guinea-Bissau 43 Liberia 44 Mali 45 Mauritania 53 Niger 56 Nigeria 60 Senegal 114 Sierra Leone 139 Togo 141 III WEST CENTRAL AFRICA 143 Angola 143 Cameroon 143 Central African Republic 147 Chad 147 Congo 149 Gabon 150 IV NORTHEAST AFRICA 151 Northeast Africa (General) 151 Eritrea 152 Ethiopia 153 Somalia 156 Sudan 160 v V EAST AFRICA 189 East Africa (General) 189 Burundi 197 Kenya 197 Mozambique 205 Rwanda 206 Tanzania 206 Uganda 212 VI INDIAN -

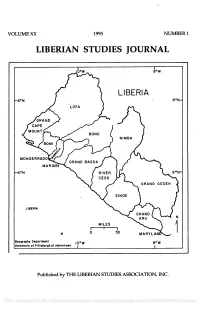

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XX 1995 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL 1 10oW 8°W LIBERIA -8°N MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6 °N RIVER 6 °N- MILES 1 1 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department 10°W 8 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown I 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor r LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editorial Policy The Liberian Studies Journal is dedicated to the publication of original research on social, political, economic and other issues about Liberia or with implications for Liberia. Opinions of contributors to the Journal do not necessarily reflect the policy of the organizations they represent or the Liberian Studies Association, publishers of the Journal. Manuscript Requirements Manuscripts submitted for publication should not exceed 25 typewritten double- spaced pages, with margins of one -and -a -half inches. The page limit includes graphs, references, tables, and appendices. Authors may, in addition to their manuscripts, submit a computer disk of their work with information about the word processing program used, i.e. WordPerfect, Microsoft Word, etc. Notes and references should be placed at the end of the text with headings (e.g. Notes; References). Notes, if any, should precede the references. The Journal is pub- lished in June and December. Deadline for submission for the first issue is February, and for the second, August. Manuscripts should include a title page that provides the title of the text, author's name, address, phone number, and affiliation. All research work will be reviewed by anonymous referees. Manuscripts are accepted in English or French. -

30 Tage Gebet Für Die Islamische Welt 2007

Tage Gebet 30 für die islamische Welt Ramadan 1428 1234567 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 13. September bis 12. Oktober 2007 Liebe Freunde und Beter! Für muslimische Gläubige ist das 30tägige Fasten Der Fastenmonat wird in Erinnerung an die Herab- im Monat Ramadan keine freiwillige Angelegenheit, sendung des Korans begangen (Sure 2,185). Der Rama- sondern – neben Bekenntnis, Gebet, Almosen und dan ist für fromme Muslime auch eine Zeit der Besin- Wallfahrt nach Mekka einmal im Leben – eine Glau- nung auf Gott, des Koranstudiums, des intensiveren benspflicht, die jedem muslimischen Mann und jeder Gebets, eine Zeit, in der die Moschee häufiger aufge- muslimischen Frau ab der Pubertät jährlich „vorge- sucht wird als sonst und oft auch eine Zeit der Versöh- schrieben ist“ (Sure 2,183). nung und der Konfliktlösung. Der Fastenmonat ist Aus- druck des Gehorsams des Gläubigen, er ist eine Prüfung Schon in frühislamischer Zeit galt die Pflicht zum des Glaubens, Besinnung auf Gottes Güte und bringt Fasten, auch wenn mit Sicherheit eine Entwicklung hin nicht zuletzt die Suche nach Wohlgefallen bei Gott zum 30tägigen Fasten stattgefunden hat. Vorbild war zum Ausdruck, der von Muslimen verlangt, zu „glauben wohl die jüdische Glaubensgemeinschaft auf der Ara- und das Rechte zu tun“ (Sure 2,25), also die Fünf Säu- bischen Halbinsel zu Muhammads Lebzeiten im 7. Jahr- len des Islam einzuhalten. hundert. Impressum Weltweit beten Christen im Ramadan in besonde- Während der 30 Tage des Ramadan muss von Son- rer Weise für Muslime, die Jesus nur als Propheten ken- u (c) 2007 Deutsche Evangelische Allianz, Esplanade 5–10a, 07422 Bad Blankenburg, nenaufgang bis Sonnenuntergang auf Essen und Trin- nen, aber ihm noch nicht als ihrem Fürsprecher beim Telefax: +49(36741)3212 ken, Parfüm, Zigaretten und Intimität verzichtet wer- Vater begegnet sind und ihre bedingungslose Annah- e-mail: [email protected], Internet: www.ead.de den. -

RIGHTS and the CIVIL WAR in LIBERIA by Janet Fleischman

VOLUME XIX 1994 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL 1 I 10°W 8°W LIBERIA -8°N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6 °N RIVER / 6 °N- MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W 8 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown I 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editorial Policy The Liberian Studies Journal is dedicated to the publication of original research on social, political, economic and other issues about Liberia or with implications for Liberia. Opinions of contributors to the journal do not necessarily reflect the policy of the organizations they represent or the Liberian Studies Association, publishers of the Journal. Manuscript Requirements Manuscripts submitted for publication should not exceed 25 typewritten double - spaced pages, with margins of one -and -a -half inches. The page limit includes graphs, references, tables, and appendices. Authors may, in addition to their manuscripts, submit a computer disk of their work with information about the word processing program used, i.e. WordPerfect, Microsoft Word, etc. Notes and references should be placed at the end of the text with headings (e.g. Notes; References). Notes, if any, should precede the references. The Journal is pub- lished in June and December. Deadline for submission for the first issue is February, and for the second, August. Manuscripts should include a title page that provides the title of the text, author's name, address, phone number, and affiliation. All research work will be reviewed by anonymous referees. Manuscripts are accepted in English or French. -

Ending Liberia's Second Civil War: Religious Women As Peacemakers

Religion and Conflict Case Study Series Ending Liberia’s Second Civil War: Religious Women as Peacemakers August 2013 © Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/resources/classroom 4 Abstract 5 This case study provides an overview of how a peace movement led by lay reli- gious women inspired people across ethnic and religious lines and helped bring 6 an end to the Second Liberian Civil War (1999-2003). The study examines this Liberian phenomenon by answering six questions: What are the causes of 8 conflict in Liberia? How did domestic religious actors promote peace? How was laity-led peacebuilding different from that of religious elites? How did domestic efforts intersect with international efforts at peace? What factors explain the success of religion-inspired peacebuilding? How did religious actors continue to promote peace in the post-conflict phase? The case study includes a core text, a timeline of key events, a guide to relevant religious organizations, and a list of further readings. 11 13 About this Case Study This case study was crafted by George Kieh under the editorial direction of Eric Patterson, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Government and associate director of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. This case study was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Founda- tion and the Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs. 2 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — LIBERIA Contents Introduction 4 Historical Background 5 Domestic Factors 6 International Factors 8 Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors 10 Resources Key Events 11 Religious Organizations 13 Further Reading 14 Discussion Questions 15 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — LIBERIA 3 Introduction On December 24, 1989, Charles Taylor’s National Patri- tion, pillaging, and forced internal displacement. -

Liberians an Introduction to Their History and Culture

Culture Profile No. 19 April 2005 Liberians An Introduction to their History and Culture Writers: Robin Dunn-Marcos, Konia T. Kollehlon, Bernard Ngovo, and Emily Russ Editor: Donald A. Ranard Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily repre- sent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the fed- eral government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic, Sharyl Tanck Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2005 ©2005 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. Liberians ii Acknowledgments Many people helped to produce this profile. The sections “People,” “History,” “Life in Liberia,” and “Education and Literacy” were written by Dr.