49460B31a3203b7.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

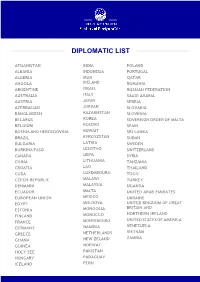

Diplomatic List

DIPLOMATIC LIST AFGANISTAN INDIA POLAND ALBANIA INDONESIA PORTUGAL ALGERIA IRAN QATAR ANGOLA IRELAND ROMANIA ARGENTINE ISRAEL RUSSIAN FEDERATION AUSTRALIA ITALY SAUDI ARABIA AUSTRIA JAPAN SERBIA AZERBAIJAN JORDAN SLOVAKIA BANGLADESH KAZAKHSTAN SLOVENIA BELARUS KOREA SOVEREIGN ORDER OF MALTA BELGIUM KOSOVO SPAIN BOSNIA AND HERCEGOVINA KUWAIT SRI LANKA BRAZIL KYRGYZSTAN SUDAN BULGARIA LATVIA SWEDEN BURKINA FASO LESOTHO SWITZERLAND CANADA LIBYA SYRIA CHINA LITHUANIA TANZANIA CROATIA LAO THAILAND CUBA LUXEMBOURG TOGO CZECH REPUBLIC MALAWI TURKEY DENMARK MALAYSIA UGANDA ECUADOR MALTA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES EUROPEAN UNION MEXICO UKRAINE EGYPT MOLDOVA UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND ESTONIA MONGOLIA NORTHERN IRELAND FINLAND MOROCCO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FRANCE MONTENEGRO VENEZUELA GERMANY NAMIBIA VIETNAM GREECE NETHERLANDS ZAMBIA GHANA NEW ZELAND GUINEA NORWAY HOLY SEE PAKISTAN HUNGARY PARAGUAY ICELAND PERU ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 57 “Simeonovsko shosse” street, Res. 3, 1700 Sofia telephone: +359 2 962-74-76 / +359 2 962-51-93 fax: +359 2 962-74-86 e-mail: [email protected] Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 09:00 - 16:00 Consular Section: Monday and Thursday 09:00 - 16:00 National Holiday: 19 August- Independence Day Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Mr. Mohammad Khalil Kargar, m. 1st Secretary REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania Slavej Planina 2, 1000 Skopje telephone: +389 2 3246 726 fax: +389 2 3246 727 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.albanianembassy.org.mk Visa Office telephone: +389 2 324 6726 – ext. 105 Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 08.00 - 16.00 Consular Section: 10.00 - 12.00 National Holiday: National Day, November 28 His Excellency Mr. -

Business and Politics in the Muslim World Asia Reports

BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD ASIA REPORTS First Quarter 2009 Volume: 2. No.-1 Reports of February, 2009 Table of contents Reports for the month of February Week-1 February 04, 2009 03 Week-2 February 11, 2009 336 Country profiles Sources 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD ASIA REPORT February 04, 2009 Nadia Tasleem: Report on Asia 04 Ashia Rehman: Report on Fertile Crescent 20 Madiha Kaukub: Report on GCC 61 Tatheer Zehra: Report on South East Asia 82 Ghashia Kayani: Report on South Asia 145 Sadia Khanum: Report on India 318 3 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD SOUTH & EAST ASIA and GCC & Fertile Crescent Nadia Tasleem Weekly Report from 26 December 2008 to 30 January 2009 Presentation: 4 February 2009 This report is based on the review of news items focusing on political, economic, social and geo‐ strategic developments in various regions namely; South Asia, East Asia, GCC and Fertile Crescent from 26 December 2008 to 30 January 2009 as have been collected by interns. Summary South Asia: Political Front: After winning 9th Parliamentary elections in Bangladesh, 258 members from winning coalition sworn in as MPs on 3 January 2009; three days later, leader of Awami League Sheikh Haseena Wajid took oath as new Premier of Bangladesh on 6 January 2009. Later on first Parliamentary session was held on 25 January that was not being attended by opposition party i.e. BNP. Besides that Upazila elections finally held on 22 January amidst few incidents of clashes. Though election in six upazila got cancelled however took place successfully in rest of the 475 upazila areas under strong security arrangements as almost 5 lakh security persons were deployed all across the country. -

Renato Mendonça: Um Intelectual Na Diplomacia”

Boletim da Associação dos Diplomatas Brasileiros Ano XIX Nº 79 Outubro/Novembro/Dezembro 2012 ISSN 0104–8503 FELIZ NATAL E UM ANO NOVO CHEIO DE REALIZAÇÕES. ADB – Associação dos Diplomatas Brasileiros Ministério das Relações Exteriores – Esplanada dos Ministérios Palácio do Itamaraty, Anexo I, 3º andar, sala 329–A 70170–900 – Brasília – Brasil Fones: (61) 3411 6950 e 3224 8022 Fax: (61) 3322 0504 www.adb.org.br – e–mail: [email protected] Carta aos Associados ormulo aos nossos Associados, em nome de toda a Diretoria da ADB, os melhores votos de saúde e de prosperidade para o Ano Novo de 2013. FO avanço brasileiro na complexa ciência da informática é fato que explica a cooperação técnica que o Brasil vem prestando a instituições públicas e privadas mundo afora. Não há milagre. A que deve a Coréia do Sul seu enorme progresso econômico? A resposta é uma só: ao investimento maciço e constante em educação. O número anterior da Boletim publicou matéria da jovem diplomata Roberta Lima sobre a Conferência Rio+20. O presente número tem a honra de acolher, sobre o tema, matéria do Senador Rodrigo Rollemberg, Senador pelo PSB/DF e Presidente da Comissão do Meio Ambiente do Senado. Desta vez, coube ao Embaixador da Tailândia -Tharit Charungvat - falar de seu país e das suas relações com o Brasil. A matéria de capa traz cifras impressionantes sobre o desenvolvimento presente e futuro do agrone- gócio no Brasil. Esta produtividade se deve, em boa parte, às pesquisas de elevadíssimo nível científico e tecnológico de uma instituição totalmente brasileira, a mundialmente renomada Embrapa, cujas atividades de cooperação técnica prestada a países estrangeiros vêm-se consolidando dia a dia. -

Diplomatic List

DIPLOMATIC LIST AFGANISTAN INDIA POLAND ALBANIA INDONESIA PORTUGAL ALGERIA IRAN QATAR ANGOLA IRELAND ROMANIA ARGENTINE ISRAEL ITALY RUSSIAN FEDERATION SAUDI AUSTRALIA JAPAN ARABIA AUSTRIA JORDAN SERBIA AZERBAIJAN KAZAKHSTAN SLOVAKIA BANGLADESH KOREA KOSOVO SLOVENIA BELARUS KUWAIT SOVEREIGN ORDER OF MALTA BELGIUM KYRGYZSTAN SPAIN BOSNIA AND HERCEGOVINA LATVIA SRI LANKA BRAZIL LESOTHO LIBYA SUDAN SWEDEN BULGARIA LITHUANIA LAO SWITZERLAND BURKINA FASO LUXEMBOURG SYRIA TANZANIA CANADA CHINA MALAWI THAILAND TOGO CROATIA MALAYSIA MALTA TURKEY CUBA MEXICO UGANDA CYPRUS MOLDOVA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES CZECH REPUBLIC MONGOLIA UKRAINE DENMARK ECUADOR MOROCCO UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT EUROPEAN UNION MONTENEGRO BRITAIN AND EGYPT NAMIBIA NORTHERN IRELAND UNITED ESTONIA NETHERLANDS STATES OF AMERICA VENEZUELA FINLAND NEW ZELAND VIETNAM FRANCE NORWAY ZAMBIA GERMANY PAKISTAN GREECE PARAGUAY PERU GHANA GUINEA HOLY SEE HUNGARY ICELAND ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 57 “Simeonovsko shosse” street, Res. 3, 1700 Sofia telephone: +359 2 962-74-76 / +359 2 962-51-93 fax: +359 2 962-74-86 e-mail: [email protected] Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 09:00 - 16:00 Consular Section: Monday and Thursday 09:00 - 16:00 National Holiday: 19 August- Independence Day Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Mr. Mohammad Khalil Kargar, First Secretary REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania Slavej Planina 2, 1000 Skopje telephone: +389 2 3246 726 fax: +389 2 3246 727 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.albanianembassy.org.mk Visa Office telephone: +389 2 324 6726 – ext. 105 Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 08.00 - 16.00 Consular Section: 10.00 - 12.00 National Holiday: National Day, November 28 His Excellency Mr. -

Corps Diplomatique

COMMUNAUTÉS EUROPÉENNES COMMISSION DIRECTION GËNËRALE DES RELATIONS EXTËRIEURES CORPS DIPLOMATIQUE accrédité auprès des Communautés européennes Octobre 1990 Une fiche bibliographique figure à la fin de l'ouvrage. Luxembourg: Office des publications officielles des Communautés européennes, 1990 ISBN 92-826-1891-9 N° de catalogue: CM-60-90-030-FR-C © CECA-CEE-CEEA, Bruxelles • Luxembourg, 1990 Reproduction autorisée, sauf à des fins commerciales, moyennant mention de la source. Printed in Luxembourg 3 PRÉSÉANCE DES CHEFS DE MISSION SAINT-SIÈGE S.E.R. Mgr Giovanni MORETII 21 décembre 1989 ÎLE MAURICE S.E. M. Raymond CHASLE 23 septembre 1976 COMORES S.E. M. Ali MLAHAILI 5 mai 1982 SUÈDE S.E. M. Stig BRATISTROM 6 octobre 1983 GAMBIE S.E. M. Abdullah Mamadu Kalifa BOJANG 23 janvier 1984 CÔTE-D'IVOIRE S.E. M. Charles Valy TUHO 14 mai 1984 MADAGASCAR S.E. M. Christian Rémi .RICHARD 14 mai 1984 GUINÉE-BISSAU S.E. M. Bubacar TURE 18 février 1985 YEMEN S.E. M. Mohammed Abdul Rehman AL-ROBAEE 18 février 1985 MOZAMBIQUE S.E. Mme Frances Vit6ria VELHO RODRIGUES 25 juillet 1985 PÉROU S.E. M. Julio EGO-AGUIRRE ALVAREZ 26 juillet 1985 PARAGUAY S.E. M. Dido FLORENTIN-BOGADO 26 juillet 1985 LIBAN S.E. M. Saïd AL-ASSAAD 21 octobre 1985 4 PRÉSÉANCE DES CHEFS DE MISSION (suite) IRAK S.E. M. Zaid Hwaishan HAIDAR 26 novembre 1985 MAURITANIE S.E. M. Ely OULD ALLAF 3 février 1986 DOMINIQUE S.E. M. Charles A. SAVARIN 29 septembre 1986 INDONÉSIE S.E. M. Atmono SURYO 29 septembre 1986 AFRIQUE DU SUD S.E. -

Diplomatic List

DIPLOMATIC LIST AFGANISTAN INDIA POLAND ALBANIA INDONESIA PORTUGAL ALGERIA IRAN QATAR ANGOLA IRELAND ROMANIA ARGENTINE ISRAEL RUSSIAN FEDERATION AUSTRALIA ITALY SAUDI ARABIA AUSTRIA JAPAN SERBIA AZERBAIJAN JORDAN SLOVAKIA BANGLADESH KAZAKHSTAN SLOVENIA BELARUS KOREA SOVEREIGN ORDER OF MALTA BELGIUM KOSOVO SPAIN BOSNIA AND HERCEGOVINA KUWAIT SRI LANKA BRAZIL KYRGYZSTAN SUDAN BULGARIA LATVIA SWEDEN BURKINA FASO LESOTHO SWITZERLAND CANADA LIBYA SYRIA CHINA LITHUANIA TANZANIA CROATIA LAO THAILAND CUBA LUXEMBOURG TOGO CZECH REPUBLIC MALAWI TURKEY DENMARK MALAYSIA UGANDA ECUADOR MALTA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES EUROPEAN UNION MEXICO UKRAINE EGYPT MOLDOVA UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND ESTONIA MONGOLIA NORTHERN IRELAND FINLAND MOROCCO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FRANCE MONTENEGRO VENEZUELA GERMANY NAMIBIA VIETNAM GREECE NETHERLANDS ZAMBIA GHANA NEW ZELAND GUINEA NORWAY HOLY SEE PAKISTAN HUNGARY PARAGUAY ICELAND PERU ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 57 “Simeonovsko shosse” street, Res. 3, 1700 Sofia telephone: +359 2 962-74-76 / +359 2 962-51-93 fax:+359 2 962-74-86 e-mail: [email protected] Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 09:00 - 16:00 Consular Section: Monday and Thursday 09:00 - 16:00 National Holiday: 19 August- Independence Day Mr. Mohammad Azam N. Ansary Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Mr. Mohammad Khalil Kargar, m. 1st Secretary REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania Slavej Planina 2, 1000 Skopje telephone: +389 2 3246 726 fax: +389 2 3246 727 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.albanianembassy.org.mk Visa Office telephone: +389 2 324 6726 – ext. 105 Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 08.00 - 16.00 Consular Section: 10.00 - 12.00 National Holiday: National Day, November 28 His Excellency Mr. -

Thailand and Cambodia

Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics Image-Formation at a Nation’s Edge: Thai Perceptions of its Border Dispute with Cambodia - Implications for South Asia by Paul W. Chambers and Siegfried O. Wolf Working Paper No. 52 February 2010 South Asia Institute Department of Political Science Heidelberg University HEIDELBERG PAPERS IN SOUTH ASIAN AND COMPARATIVE POLITICS ISSN: 1617-5069 About HPSACP This occasional paper series is run by the Department of Political Science of the South Asia Institute at the University of Heidelberg. The main objective of the series is to publicise ongoing research on South Asian politics in the form of research papers, made accessible to the international community, policy makers and the general public. HPSACP is published only on the Internet. The papers are available in the electronic pdf-format and are designed to be downloaded at no cost to the user. The series draws on the research projects being conducted at the South Asia Institute in Heidelberg, senior seminars by visiting scholars and the world-wide network of South Asia scholarship. The opinions expressed in the series are those of the authors, and do not represent the views of the University of Heidelberg or the Editorial Staff. Potential authors should consult the style sheet and list of already published papers at the end of this article before making a submission. Editor Subrata K. Mitra Deputy Editors Clemens Spiess Malte Pehl Jivanta Schöttli Siegfried O. Wolf Anja Kluge Managing Editor Florian Britsch Editorial Assistant Sergio Mukherjee Editorial Advisory Board Mohammed Badrul Alam Barnita Bagchi Dan Banik Harihar Bhattacharyya Mike Enskat Alexander Fischer Karsten Frey Partha S. -

Order of Precedence and Date of Presentation of Credentials

ORDER OF PRECEDENCE AND DATE OF PRESENTATION OF CREDENTIALS Azerbaijan H.E. Mr. Faig Baghirov (Resident in Ankara) 6 September 2011 Paraguay H.E. Mr. Esteban Kriskovic (Resident in Roma) 19 December 2011 Holy See H.E. Mr. Archbishop Anselmo Gvido Pekorari (Resident in Sofia) 24 July 2014 Thailand H.E. Mr. Tharit Charungvat (Resident in Ankara) 25 July 2014 Israel H.E. Mr. Dan Oryan (Resident in Jerusalem) 21 August 2014 Algeria H.E. Mrs. Taous Djellouli (Resident in Bucharest) 28 October 2014 Namibia H.E. Mr. Simon Madjumo Maruta, (Resident in Vienna) 22 January 2015 Albania H.E. Mr. Fatos Reka, Dean of the Diplomatic Corps 26 July 2015 Venezuela H.E. Mrs. Orietta Caponi (Resident in Sofia) 30 September 2015 Switzerland H.E. Mrs. Sybille Suter Tejada 20 January 2016 DPR Korea H.E. Mr. Cha Kon Il (Resident in Sofia) 21 January 2016 Togo H.E. Mr. Kwami Christophe Dikenou (Resident in Berlin) 26 February 2016 Sudan H.E. Mrs. Ilham Ibrahim Mohamed Ahmed (Resident in Sofia) 25 March 2016 Ecuador H.E. Mr. Juan Holguin Flores (Resident in Rome) 24 June 2016 Pakistan H.E. Mr. Sohail Mahmood (Resident in Ankara) 24 June 2016 Hungary H.E. Mr. László István Dux 19 August 2016 Morocco H.E. Mrs. Zakia El Midaoui (Resident in Sofia) 22 December 2016 Burkina Faso H.E. Mr. Amadou Dicko (Resident in Ankara) 22 December 2016 Moldova H.E. Mr. Ștefan Gorda (Resident in Sofia) 10 March 2017 Mongolia H.E. Mr. Dashjamts Batsaikhan (Resident in Sofia) 30 May 2017 Peru H.E. -

Provisional List of Delegations to the United Nations Conference on Sustanable Development Rio+20 I Member States

PROVISIONAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON SUSTANABLE DEVELOPMENT RIO+20 I MEMBER STATES AFGHANISTAN H.E. Mr. Zalmai Rassoul, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Representatives H.E. Mr. Wais Ahmad Barmak, Minister of Rural Rehabilitation and Development H.E. Mr. Mohammad Asif Rahimi, Minister of Agriculture, Irrigation and Animal Husbandry H.E. Prince Mustapha Zahir, President of National Environment Protection Agency H.E. Mr. Jawed Ludin, Deputy Foreign Minister H.E. Sham Lal Batijah, Senior Economic Adviser to the President H.E. Mr. Zahir Tanin, Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations Mr. Mohammad Erfani Ayoob, Director General, United Nations and International Conferences Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Ershad Ahmadi, Director General of Fifth Political Department Mr. Janan Mosazai, Spokesperson, Ministry for Foreign Affairs Mr. Enayetullah Madani, Permanent Mission of Afghanistan to the UN Mr. Aziz Ahmad Noorzad, Deputy Chief of Protocol, Ministry for Foreign Affairs Ms. Kwaga Kakar, Adviser to the Foreign Minister Ms. Ghazaal Habibyar, Director General of Policies, Ministry of Mine Mr. Wahidullah Waissi, Adviser to the Deputy Foreign Minister 2 ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Fatmir Mediu, Minister for Environment, Forests and Water Administration of the Republic of Albania Representatives H.E. Mr. Ferit Hoxha, Ambassador Permanent Representative to the United Nations H.E. Mrs. Tajiana Gjonaj, Ambassador to Brazil Mr. Oerd Bylykbashi, Chief of Cabinet of the Prime Minister Mr. Glori Husi, Adviser to the Prime Minister Mr. Abdon de Paula, Honorary Consul to Rio de Janeiro Mr. Thomas Amaral Neves, Honorary Consul to São Paulo Mr. -

14Th ASEAN Summit with Dialogue Partners Postponed (11/4/2009)

14th ASEAN Summit with Dialogue Partners Postponed (11/4/2009) Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva has decided to postpone the ASEAN Plus Three Summit and the ASEAN Plus Six Summit to a later date due to massive demonstrations led by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD). The meetings began at the Royal Cliff Beach Hotel in Pattaya, Chon Buri, on April 10 and were due to end on April 12. The Prime Minister on April 11 cancelled them, after UDD had caused disturbances and disorder in its protests against the Thai government. Mr. Tharit Charungvat, Director-General of the Department of Information and Foreign Ministry Spokesman, said that Prime Minister Abhisit convened a meeting with ASEAN leaders already present at the meeting venue. He also made telephone calls to ASEAN dialogue partners, who had come for the summits, to inform them of the decision to postpone the meeting. The Prime Minister expressed his apology for the inconvenience caused, saying that Thailand would coordinate with them regarding the new schedule of meetings. At the summits, 10 ASEAN countries had expected to hold talks with six dialogue partners, namely China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand. All ASEAN and dialogue partners expressed their understanding and hoped that the Royal Thai Government would be able to find an early resolution to the situation. They also reaffirmed their readiness to cooperate toward the reconvening of the summits on a date which would be set later. In the meantime, the Government decided to impose a state of emergency in Pattaya and other areas in Chon Buri on April 11. -

Corps Diplomatique

COMMISSION EUROPÉENNE CORPS DIPLOMATIQUE accrédité auprès des Communautés européennes et représentations auprès de la Commission Octobre 1994 Une fiche bibliographique figure à la fin de l'ouvrage. Luxembourg: Office des publications officielles des Communautés européennes, 1994 ISBN 92-826-9340-6 Reproduction autorisée, sauf à des fins commerciales, moyennant mention de la source. Printed in Luxembourg 3 PRÉSÉANCE DES CHEFS DE MISSION SAINT-SIÈGE S.E.R. Mgr Giovanni MORETII .......................... 21 décembre 1989 MADAGASCAR S.E. M. Christian Rémi RICHARD ............................ 14 mai 1984 MOZAMBIQUE S.E. MmeFrances Victoria VELHO RODRlGUEZ ............... 25 juillet 1985 MALAWI S.E. M. Lawrence ANTHONY ................................ 8 mai 1987 BOTSWANA S.E. M. Ernest MPOFU . 8 mai 1987 BARBADE S.E. M. Rashid MARVILLE .............................. 22 octobre 1987 OMAN S.E. M. Munir bin Abdulnabi bin Youssef MAKKI .......... 27 septembre 1988 FIDJI S.E. M. Kaliopate TAVOLA .............................. 25 octobre 1988 LIBYE S.E. M. Mohamed ALFAITURI ............................ 24 janvier 1989 KOWEÏT S.E. M. Ahmad AL-EBRAHIM ............................ 24 janvier 1989 NORVÈGE S.E. M. Eivinn BERG ..................................... 3 février 1989 LESOTHO S.E. M. Mabotse LEROTHOLI ............................. 20 février 1989 SÉNÉGAL S.E. M. Falilou KANE .................................... 21 février 1989 4 PRÉSÉANCE DES CHEFS DE MISSION (suite) ÉMIRATS ARABES UNIS S.E. M. Salem Rached Salem AL-AGROOBI ................. 21 février 1989 CAMEROUN S.E. MMqsabelle BASSONG . 10 octobre 1989 ZAÏRE S.E. M. KIMBULU M. Wa LOKWA . 7 novembre 1989 URUGUAY S.E. M. José Maria ARANEO . 7 novembre 1989 CHYPRE S.E. M. Nicos AGATHOCLEOUS . 7 novembre 1989 ANTIGUE ET BARBUDE S.E. M. James THOMAS 9 novembre 1989 DJIBOUTI S.E. -

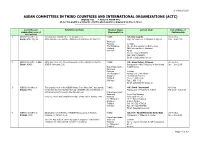

Asean Committees in Third Countries And

As of March 2015 ASEAN COMMITTEES IN THIRD COUNTRIES AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS (ACTC) (Highlighted) = ACTCs in ASEAN DPs) (Note: This matrix is a living list of ACTCs which would be updated from time to time) --------------------------------------------------------------- Committee (in Establishment Date Member States Current Chair Period/Dates of alphabetical order of Representation Chairmanship the Capitals) 1. ASEAN Committee in The ACA was established on 31 January 2012. 5 AMS: H.E. Lim Juay Jin Six months: Abuja (ACA), Nigeria AFMs formally endorsed the establishment of ACA on 31 July 2012 High Commissioner of Malaysia to Nigeria Mar – Sept 2015 Indonesia Malaysia Contact: The Philippines No. 4A, Plot 2232 B, Rio Negro Close Thailand Off Yedseram Street, Maitama Viet Nam Abuja Phone: (234) 9 7809379 Fax: (234) 9 7822671 Email: [email protected] 2. ASEAN Committee in Abu AFMs gave their ad-ref formal approval on the establishment of the 7 AMS: H.E. Grace Relucio Princesa Six months: Dhabi (ACAD) ACAD in November 2011 Ambassador of the Philippines to the United Jan – June 2015 Brunei Darussalam Arab Emirates Indonesia Malaysia Contact: The Philippines PO BOX 3215, Abu Dhabi Singapore United Arab Emirates Thailand Phone: 2-639-0006 Viet Nam Fax: 2-639-0002 Email: [email protected] 3. ASEAN Committee in The establishment of the ASEAN Ankara Committee (AAC) was agreed 7 AMS: H.E. Tharit Charungvat One Year Ankara (AAC) by the ASC and the Secretary-General of ASEAN sent a notification on Ambassador of Thailand to Turkey Feb 2015 - Jan 2016 22 February 2007 conveying the ASC approval. Brunei Darussalam Indonesia Royal Thai Embassy However, the formal establishment date of ACC was 1 January 2009.