A Spy of His Own Confession: a Revolution in American Espionage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pof: Proof-Of-Following for Vehicle Platoons

Verification of Platooning using Large-Scale Fading Ziqi Xu* Jingcheng Li* Yanjun Pan University of Arizona University of Arizona University of Arizona [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Loukas Lazos Ming Li Nirnimesh Ghose University of Arizona University of Arizona University of Nebraska–Lincoln [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Cooperative vehicle platooning significantly im- I am AV proves highway safety, fuel efficiency, and traffic flow. In this 2 and I follow AV model, a set of vehicles move in line formation and coordinate 1 acceleration, braking, and steering using a combination of path physical sensing and vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) messaging. The candidate verifier authenticity and integrity of the V2V messages are paramount to platooning AV AV safety. For this reason, recent V2V and V2X standards support 2 distance 1 the integration of a PKI. However, a PKI cannot bind a vehicle’s digital identity to the vehicle’s physical state (location, velocity, Fig. 1: Platooning of AV1 and AV2: The AV1 acts as a verifier etc.). As a result, a vehicle with valid cryptographic credentials to validate AV2’s claim that it follows the platoon. can impact platoons from a remote location. In this paper, we seek to provide the missing link between the However, the complex integration of multi-modal physical physical and the digital world in the context of vehicle platooning. sensing, computation, and communication creates a particu- We propose a new access control protocol we call Proof-of- larly challenging environment to safeguard. The safety of the Following (PoF) that verifies the following distance between a platoon relies on the veracity of the V2V messages exchanged candidate and a verifier. -

The Spies That Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Lew, Masaki, "The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 19. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/19 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Humanities Western Civilization 102 March 16, 2020 1 Continental Spy Nathan Hale, standing below the gallows, spoke to his British captors with nothing less than unequivocal patriotism: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”1 American History idolizes Hale as a hero. His bravery as the first pioneer of American espionage willing to sacrifice his life for the growing colonial sentiment against a daunting global empire vindicates this. Yet, behind Hale’s success as an operative on -

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge the Following Excerpts Were Prepared by Col

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge The following excerpts were prepared by Col. Benjamin Tallmadge THE SUBJECT OF THIS memoir was born at Brookhaven, on Long Island, in Suffolk county, State of New York, on the 25th of February, 1754. His father, the Rev. Benjamin Tallmadge, was the settle minister of that place, having married Miss Susannah Smith, the daughter of the Rev. John Smith, of White Plains, Westchester county, and State of New York, on the 16th of May, 1750. I remember my grandparents very well, having visited them often when I was young. Of their pedigree I know but little, but have heard my grandfather Tallmadge say that his father, with a brother, left England together, and came tot his country, one settling at East Hampton, on Long Island, and the other at Branford, in Connecticut. My father descended from the latter stock. My father was born at New Haven, in this State, January 1st, 1725, and graduated at Yale College, in the year 1747, and was ordained at Brookhaven, or Setauket, in the year 1753, where he remained during his life. He died at the same place on the 5th of February, 1786. My mother died April 21st, 1768, leaving the following children, viz.: William Tallmadge, born October 17, 1752, died in the British prison , 1776. Benjamin Tallmadge, born February 25, 1754, who writes this memoranda. Samuel Tallmadge, born November 23, 1755, died April 1, 1825. John Tallmadge, born September 19, 1757, died February 24, 1823. Isaac Tallmadge, born February 25, 1762. My honored father married, for his second wife, Miss Zipporah Strong, January 3rd, 1770, by whom he had no children. -

Joseph Saunders 1713–1792

Chapter 2 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713-1792 1 Chapter Two Revised January 2021 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713–1792 From Great Britain to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1708 England 3 Joseph Saunders = Susannah Child . c.1685 4 Mary Sarah JOSEPH SAUNDERS Timothy John Richard 1709– 1711– 1713–1792 1714– 1716– 1719– m. Hannah Reeve OSEPH4 SAUNDERS was born on the 8th day of January 1712/1713 at Farnham Royal, County of Bucks, Great Britain in the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714). The records of the Society of Friends in England, Buckinghamshire Quaker Records, Upperside Meeting, indicate that Joseph was the third child and eldest son of Joseph3 Saunders, wheelwright, who on 17th June 1708 had married Susannah Child, the daughter of a prominent Quaker family. He had three brothers and two sisters. Register of Births belonging to the Monthly Meeting of Upperside, Buckinghamshire from 1656–1775, TNA Ref. RG6 / Piece 1406 / Folio 23: Missing from the account of Joseph4 Saunders is information on his early life in Britain: the years leading up to 1732 when he left for America. He was obviously well educated with impressive handwriting skills and had a head for numbers. Following Quaker custom, his father, who was a wheelwright, would have apprenticed young Joseph when he was about fourteen to a respectable Quaker merchant. When he arrived in America at the age of twenty he knew how to go about setting himself up in business and quickly became a successful merchant. The Town Crier 2 Chapter 2 JOSEPH4 SAUNDERS 1713-1792 The Quakers Some information on the Quakers, their origins and beliefs will help the reader understand the kind of society in which Joseph was reared and dwelt. -

THE SPY WHO FIRED ME the Human Costs of Workplace Monitoring by ESTHER KAPLAN

Garry Wills on the u A Lost Story by u William T. Vollmann Future of Catholicism Vladimir Nabokov Visits Fukushima HARPER’S MAGAZINE/MARCH 2015 $6.99 THE SPY WHO FIRED ME The human costs of workplace monitoring BY ESTHER KAPLAN u A GRAND JUROR SPEAKS The Inside Story of How Prosecutors Always Get Their Way BY GIDEON LEWIS-KRAUS GIVING UP THE GHOST The Eternal Allure of Life After Death BY LESLIE JAMISON REPORT THE SPY WHO FIRED ME The human costs of workplace monitoring By Esther Kaplan ast March, Jim data into metrics to be Cramer,L the host of factored in to your per- CNBC’s Mad Money, formance reviews and devoted part of his decisions about how show to a company much you’ll be paid. called Cornerstone Miller’s company is OnDemand. Corner- part of an $11 billion stone, Cramer shouted industry that also at the camera, is “a includes workforce- cloud-based-software- management systems as-a-service play” in the such as Kronos and “talent- management” “enterprise social” plat- field. Companies that forms such as Micro- use its platform can soft’s Yammer, Sales- quickly assess an em- force’s Chatter, and, ployee’s performance by soon, Facebook at analyzing his or her on- Work. Every aspect of line interactions, in- an office worker’s life cluding emails, instant can now be measured, messages, and Web use. and an increasing “We’ve been manag- number of corporations ing people exactly the and institutions—from same way for the last cosmetics companies hundred and fifty to car-rental agencies— years,” Cornerstone’s are using that informa- CEO, Adam Miller, tion to make hiring told Cramer. -

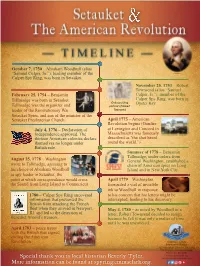

Special Thank You to Local Historian Beverly Tyler. More Information Can Be Found at Spyring.Emmaclark.Org

October 7, 1750 – Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper, Sr.”), leading member of the Culper Spy Ring, was born in Setauket. November 25, 1753 – Robert Townsend (alias “Samuel February 25, 1754 – Benjamin Culper, Jr.”), member of the Tallmadge was born in Setauket. Culper Spy Ring, was born in Only surviving Oyster Bay. Tallmadge was the organizer and portrait of Robert leader of the Revolutionary War Townsend Setauket Spies, and son of the minister of the Setauket Presbyterian Church. April 1775 – American Revolution begins (Gunfire July 4, 1776 – Declaration of at Lexington and Concord in Independence approved. The Massachusetts was famously thirteen American colonies declare described as "the shot heard themselves no longer under round the world.”) British rule. Summer of 1778 – Benjamin Tallmadge, under orders from August 25, 1778 – Washington General Washington, established a wrote to Tallmadge, agreeing to chain of American spies on Long his choice of Abraham Woodhull Island and in New York City. as spy leader in Setauket, the point at which correspondence would cross April 1779 – Washington the Sound from Long Island to Connecticut. forwarded a vial of invisible ink to Woodhull in response 1780 – Culper Spy Ring uncovered to his concern that his letters might be information that prevented the intercepted, leading to his discovery. British from attacking the French fleet when they arrived in Newport, May 4, 1780 – as noted by Woodhull in a RI. and led to the detection of letter, Robert Townsend decided to resign Benedict Arnold’s treason. because he felt it was only a matter of time until he was uncovered. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 21

K<^' ^ V*^'\^^^ '\'*'^^*/ \'^^-\^^^'^ V' ar* ^ ^^» "w^^^O^o a • <L^ (r> ***^^^>^^* '^ "h. ' ^./ ^^0^ Digitized by the internet Archive > ,/- in 2008 with funding from ' A^' ^^ *: '^^'& : The Library of Congress r^ .-?,'^ httpy/www.archive.org/details/pewyorkgepealog21 newy THE NEW YORK Genealogical\nd Biographical Record. DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XXL, 1890. 868; PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY, Berkeley Lyceuim, No. 23 West 44TH Street, NEW YORK CITY. 4125 PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Rev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS, Chairman. Dr. SAMUEL S. PURPLE.. Gen. JAS. GRANT WILSON. Mr. THOS. G. EVANS. Mr. EDWARD F. DE LANCEY. Mr. WILLL\M P. ROBINSON. Press of J. J. Little & Co., Astor Place, New York. INDEX OF SUBJECTS. Albany and New York Records, 170. Baird, Charles W., Sketch of, 147. Bidwell, Marshal] S., Memoir of, i. Brookhaven Epitaphs, 63. Cleveland, Edmund J. Captain Alexander Forbes and his Descendants, 159. Crispell Family, 83. De Lancey, Edward F. Memoir of Marshall S. Bidwell, i. De Witt Family, 185. Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Edsall, Thomas H. Inscriptions from the Dyckman Burial Ground, 81. Evans, Thomas G. The Crispell Family, 83. The De Witt Family, 185. Fernow, Berlhold. Albany and New York Records, 170 Fishkill and its Ancient Church, 52. Forbes, Alexander, 159. Heermans Family, 58. Herbert and Morgan Records, 40. Hoes, R. R. The Negro Plot of 1712, 162. Hopkins, Woolsey R Two Old New York Houses, 168. Inscriptions from Morgan Manor, N. J. , 112. John Hart, the Signer, 36. John Patterson, by William Henry Lee, 99. Jones, William Alfred. The East in New York, 43. Kelby, William. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

Benjamin Tallmadge Trail Guide.P65

Suffolk County Council, BSA The Benjamin Tallmadge Historic Trail Suffolk County Council, BSA Brookhaven, New York The starting point of this Trail is the Town of Brookhaven parking lot at Cedar Beach just off Harbor Beach Road in Mount Sinai, NY. Hikers can be safely dropped off at this loca- tion. 90% of this trail follows Town roadways which closely approximate the original route that Benjamin Tallmadge and his contingent of Light Dragoons took from Mount Sinai to the Manor of St. George in Mastic. Extreme CAUTION needs to be observed on certain heavily traveled roads. Some Town roads have little or no shoulders at all. Most roads do not have sidewalks. Scouts should hike in a single line fashion facing the oncoming traffic. They should be dressed in their Field Uniforms or brightly colored Class “B” shirt. This Trail should only be hiked in the daytime hours. Since this 21 mile long Trail is designed to be hiked over a two day period, certain pre- arrangements must be made. The overnight camping stay can be done at Cathedral Pines County Park in Middle Island. Applications must be obtained and submitted to the Suffolk County Parks Department. On Day 2, the trail veers off Smith Road in Shirley onto a ser- vice access road inside the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge for about a mile before returning to the neighborhood roads. As a courtesy, the Wertheim Refuge would like a letter three weeks in advance informing them that you will be hiking on their property. There are no water sources along this hike so make sure you pack enough. -

I Spy Activity Sheet

Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Decipher the Cipher! You are a member of the Culper Ring, an espionage organization from the Revoutionary War. Practice your ciphering skills by decoding the inspiring words of a famous patriot. G Use these keys to decipher the code above. As you can see, the key is made up of two diagrams with letters inside. To decode the message, match the coded symbols above to the letters in the key. If the symbol has no dot, use the first letter in the key. If the symbol has a dot, use the second letter. A B C D E F S T G H I J K L Y Z U V W X M N O P Q R For example, look at the first symbol of the code. The highlighted portion of the key has the same shape as the first symbol. That shape has two letters in it, a “G” and an “H”. The first symbol in the code has no dot, so it must stand for the letter “G”. When you’re done decoding the message, try using the key to write messages of your own! Did You Know? Spying was a dangerous business! Nathan Hale, a spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolution, was executed by the British on September 22, 1776. It was then that he uttered his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” © Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation • P.O. Box 1607, Williamsburg, VA 23187 June 2015 Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Un-Mask a Secret! A spy gave you the secret message below. -

SOCIAL STUDIES SUGGESTED UNITS and RESOURCES: HISTORIC MOMENTS DRAMATIZED in PEGGY's NARRATIVE Windows Onto Critically Import

SOCIAL STUDIES SUGGESTED UNITS and RESOURCES: HISTORIC MOMENTS DRAMATIZED IN PEGGY’S NARRATIVE Windows onto Critically Important but Less Discussed Aspects of the American Revolution Letters reveal that Peggy was the only one of the famed Schuyler Sisters to be in the right place at the right time to witness and potentially aid the work of her father, Philip Schuyler—as commanding general and war strategist during the Northern Campaign; as George Washington's most trusted spy-master; as the Patriots’ chief negotiator with the Iroquois Confederacy; and as liaison with French troops under Rochambeau. Peggy’s real life story illuminates the fight in upstate New York and oft overlooked elements of the war, such as: 1. The Battle of Saratoga—the Revolution’s most important turning point in terms of convincing the French to ally with us. It was Philip Schuyler’s spies who discovered the Brits’ deadly three-prong invasion strategy; Philip Schuyler who rallied the militia, slowed the British advance, and prepared the Patriots to win their first major victory. https://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/education/classrooms/the-battles-of-saratoga-reading- activity.htm https://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/kidsyouth/upload/SRA_Elementary_v3.pdf https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/93saratoga/93saratoga.htm https://study.com/academy/lesson/battle-of-saratoga-lesson-plan.html http://www.discoveryeducation.com/teachers/free-lesson-plans/the-american- revolution-saratoga-to-valley-forge.cfm http://historyanimated.com/verynewhistorywaranimated/?page_id=319 Lead-up to the battle: Fort Ticonderoga https://www.fortticonderoga.org/education/educators/resources-by-subject 2. Spying and counter-intelligence in our fight against a superior force. -

Traveling to Tennessee the 127Th Annual National Congress

Spring 2017 Vol. 111, No. 4 Traveling to Tennessee The 127th Annual National Congress SAR visits Knoxville Spring 2017 Vol. 111, No. 4 ON THE COVER Clockwise from top left, James White Fort, Knoxville Convention Center, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Museum of Appalachia, World’s Fair Park Sunsphere and Cherokee Country Club 6 8 6 Commemoration of the Battle 10 Yorktown Dedication 19 Georgia’s Yazoo Land Fraud of Great Bridge 11 Inducting a Young Jefferson 21 Moses Doan and Robert Gibson 6 USS Louisville Crew Visits Namesake City 12 Educational Outreach 22 The Life of Roger Sherman Southern District Meeting Books for Consideration 7 Kansas’ New Revolutionary 13 24 War Memorial 14 Spring Trustees Meeting 26 State Society & Chapter News 8 2017 Congress to Convene in Knoxville 15 PGs Wall Returns 38 In Our Memory/ New Members 10 Historian Jon Meacham to 16 Hamilton’s Advice for the SAR: Speak at Congress Take a Shot! 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths.