Cesifo Working Paper No. 6468 Category 5: Economics of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

BOPI N° 06NC/2019 Du 16 Avril 2020 Du N° 155329 Au N° 156328

Bulletin Officiel de la Propriété Industrielle (BOPI) Noms Commerciaux PUBLICATION N° 06 NC / 2019 du 16 Avril 2020 Organisation Africaine de la Propriété OAPI Intellectuelle BOPI 06NC/2019 GENERALITES SOMMAIRE TITRE PAGES PREMIERE PARTIE : GENERALITES 2 Extrait de la norme ST3 de l’OMPI utilisée pour la représentation des pays et organisations internationales 3 Clarification du Règlement relatif à l’extension des droits suite à une nouvelle adhésion à l’Accord de Bangui 4 Adresses utiles 5 DEUXIEME PARTIE : NOMS COMMERCIAUX 6 Noms Commerciaux du N° 155329 au N° 156328 7 1 BOPI 06NC/2019 GENERALITES PREMIERE PARTIE GENERALITES 2 BOPI 06NC/2019 GENERALITES Extrait de la norme ST.3 de l’OMPI Code normalisé à deux lettres recommandé pour la représentation des pays ainsi que d’autres entités et des organisations internationales délivrant ou enregistrant des titres de propriété industrielle. Bénin* BJ Burkina Faso* BF Cameroun* CM Centrafricaine,République* CF Comores* KM Congo* CG Côte d’Ivoire* CI Gabon* GA Guinée* GN Guinée-Bissau* GW GuinéeEquatoriale* GQ Mali* ML Mauritanie* MR Niger* NE Sénégal* SN Tchad* TD Togo* TG *Etats membres de l’OAPI 3 BOPI 06NC/2019 GENERALITES CLARIFICATION DU REGLEMENT RELATIF A L’EXTENSION DES DROITS SUITE A UNE NOUVELLE ADHESION A L’ACCORD DE BANGUI RESOLUTION N°47/32 LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’ORGANISATION AFRICAINE DE LAPROPRIETE INTELLECTUELLE Vu L’accord portant révision de l’accord de Bangui du 02 Mars demande d’extension à cet effet auprès de l’Organisation suivant 1977 instituant une Organisation Africaine de la Propriété les modalités fixées aux articles 6 à 18 ci-dessous. -

Mali Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Africa MRG Directory –> Mali –> Mali Overview Print Page Close Window Mali Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment The Republic of Mali is a landlocked state in West Africa that extends into the Sahara Desert in the north, where its north-eastern border with Algeria begins. A long border with Mauritania extends from the north, then juts west to Senegal. In the west, Mali borders Senegal and Guinea; to the south, Côte d'Ivoire; to the south-east Burkina Faso, and in the east, Niger. The country straddles the Sahara and Sahel, home primarily to nomadic herders, and the less-arid south, predominately populated by farming peoples. The Niger River arches through southern and central Mali, where it feeds sizeable lakes. The Senegal river is an important resource in the west. Mali has mineral resources, notably gold and phosphorous. Peoples Main languages: French (official), Bambara, Fulfulde (Peulh), Songhai, Tamasheq. Main religions: Islam (90%), traditional religions (6%), Christian (4%). Main minority groups: Peulh (also called Fula or Fulani) 1.4 million (11%), Senoufo and Minianka 1.2 million (9.6%), Soninké (Saracolé) 875,000 (7%), Songhai 875,000 (7%), Tuareg and Maure 625,000 (5%), Dogon 550,000 (4.4%) Bozo 350,000 (2.8%), Diawara 125,000 (1%), Xaasongaxango (Khassonke) 120,000 (1%). [Note: The percentages for Peulh, Soninke, Manding (mentioned below), Songhai, and Tuareg and Maure, as well as those for religion in Mali, come from the U.S. State Department background note on Mali, 2007; Data for Senoufo and Minianka groups comes from Ethnologue - some from 2000 and some from 1991; for Dogon from Ethnologue, 1998; for Diawara and Xaasonggaxango from Ethnologue 1991; Percentages are converted to numbers and vice-versa using the State Department's 2007 estimated total population of 12.5 million.] Around half of Mali's population consists of Manding (or Mandé) peoples, including the Bambara (Bamana) and the Malinké. -

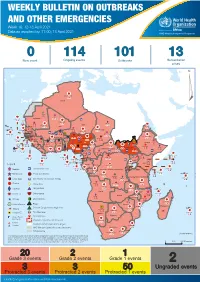

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Experiencing Islam: Women's Accounts of Religious Equality And

Experiencing Islam: Women’s Accounts of Religious Equality and Inequality in Senegal Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Anthropology Janet McIntosh, Advisor Undergraduate Program in International and Global Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of the Arts by Nelly Schläfereit May 2015 Copyright by Nelly Schläfereit Committee members: Janet McIntosh – Anthropology Anita Hannig – Anthropology Kristen Lucken – International and Global Studies Declaration This senior honors thesis is submitted for review by the Anthropology Department of Brandeis University for consideration of departmental honors to Nelly Schläfereit in May of 2015. With regard to the above, I declare that this is an original piece of work and that all non-cited writing is my own. Acknowledgements I would like to take a moment to thank all of the people who have been directly and indirectly involved in producing this senior honors thesis. First, I would like the thank the entire department of Anthropology at Brandeis who made it possible for me to undertake this project despite the fact that I was planning on studying abroad during the fall semester. I would especially like to thank Professor Janet McIntosh, my primary advisor. Thank you for supporting me throughout this process, encouraging me when I had difficulties moving forward, and always making time to offer me your invaluable advice. Thank you also to Professor Anita Hannig for being my second reader, especially considering you were not officially on campus this semester. I was lucky to have my second reader so involved throughout the research and writing process, and I appreciate all of your advice and edits. -

Mapping of Child Protection Accountability Mechanisms in Armed Conflict in Africa

1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Save the Children Somalia MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA SAVE THE CHILDREN 1 MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA ARMED CONFLICT IN MECHANISMS IN ACCOUNTABILITY MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION Save the Children Somalia 2 SAVE THE CHILDREN Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. We save children’s lives. We fight for their rights. We help them fulfil their potential. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Our vision A world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and participation. Our mission To inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children and to achieve immediate and lasting change in their lives. We will stay true to our values of accountability, ambition, collaboration, creativity and integrity. Published by: Save the Children International East and Southern Africa Regional Office Regional Programming Unit Protecting Children in Conflict P.O. Box 19423-00202 Nairobi, Kenya Cellphone: +254 711 090 000 [email protected] www.savethechildren.net Save the Children East & Southern Africa Region SaveTheChildren E&SA @ESASavechildren https://www.youtube.com/channel/ UCYafJ7mw4EutPvYSkpnaruQ Project Lead: Anthony Njoroge Technical Lead: Fiona Otieno Reviewers: Simon Kadima, Joram Kibigo, Maryline Njoroge, Alexandra Chege, Mory Camara, Måns Welander, Anta Fall, Liliane Coulibaly, and Rita Kirema. © Save the Children International August 2019 Photos: Save the Children SAVE THE CHILDREN 3 Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. -

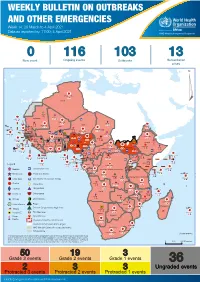

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146 -

Collège Elémentaire Prescolaire

ELECTIONS DE REPRESENTATIVITE SYNDICALE DANS LE SECTEUR DE L'EDUCATION ET DE LA FORMATION COLLEGE ELEMENTAIRE PRESCOLAIRE IA DIOURBEL MATRICULE PRENOMS ENSEIGNANT NOM ENSEIGNANT DATE NAISS ENSEIGNANTLIEU NAISSANCE ENSEIGNANT SEXE CNI NOM ETABLISSEMENT IEF DEPT REGION 603651/G Ismaïla DJIGHALY 1975-09-14 00:00:00GOUDOMP M 1146199100521 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 683343/A CONSTANCE OLOU FAYE 1971-10-10 00:00:00FANDENE THEATHIE F 2631200300275 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 650740/B IBOU FAYE 1977-03-12 00:00:00NDONDOL M 1207198800622 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 689075/I DAOUDA GNING 1986-01-01 00:00:00BAMBEY SERERE M 1202199900024 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 161201019/A MAREME LEYE 1986-01-19 00:00:00MBACKE M 2225198600234 AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 220021018/H ALIOU NDIAYE 1989-01-10 00:00:00MBARY M AK YAYE IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 120201103/Z BABACAR DIENG 1968-07-16 00:00:00TOUBA M 1238200601660 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130601117/B SOPHIE DIOP 1977-07-03 00:00:00Thiès F 2619197704684 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 642421/A Aboubacar Sadekh DIOUF 1979-06-02 00:00:00LAMBAYE M 1239199301074 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201133/D ABDOU KHADRE D GUEYE 1974-04-11 00:00:00BAMBEY M 1191197400376 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201063/H Assane KANE 1986-05-13 00:00:00BAMBEY M 1191199901066 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 635869/C MOUHAMADOU LAMINE BARA MBAYE 1981-10-20 00:00:00LAMBAYE M 1239199900506 ALAZAR BAMBEY IEF Bambey Bambey Diourbel 130201106/B -

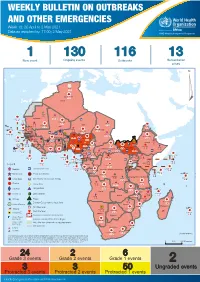

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

THE POLITICS and POLICY of DECENTRALIZATION in 1990S MALI

THE POLITICS AND POLICY OF DECENTRALIZATION IN 1990s MALI Elizabeth A. Pollard Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the African Studies Program, Indiana University August 2014 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Osita Afoaku, PhD ____________________________________ Maria Grosz-Ngaté, PhD ____________________________________ Jennifer N. Brass, PhD ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………………... i Acceptance Page ………………………………………………………………………………… ii Chapters Chapter 1 ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 2 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 Chapter 3 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 35 Chapter 4 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 49 Chapter 5 ……………………………………………………………………………….. 72 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 82 References ……………………………………………………………………………………… 84 Curriculum Vitae iii CHAPTER 1 Introduction A. Statement of the Problem At the end of the Cold War, the government of Mali, like governments across Africa, faced increased pressure from international donors and domestic civil society to undertake democratic reforms. In one notable policy shift, French President François Mitterrand made clear to his African counterparts at the June 1990 Franco-African summit, that while France was committed to supporting its former colonies through the economic -

Country Profiles

1 2017 ANNUAL2018 REPORT:ANNUAL UNFPA-UNICEF REPORT GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE COUNTRY PROFILES UNFPA-UNICEF GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE The Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage is generously funded by the Governments of Belgium, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom and the European Union and Zonta International. Front cover: © UNICEF/UNI107875/Pirozzi © United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH COUNTRYCOUNTRY PROFILE PROFILE © UNICEF/UNI179225/LYNCH BANGLADESH COUNTRY PROFILE 3 2 RANGPUR 1 1 2 2 1 3 2 1 1 Percentage of young women SYLHET (aged 20–24) married or in RAJSHAHI 59 union by age 18 DHAKA 2 2 Percentage of young women 1 KHULNA (aged 20–24) married or in CHITTAGONG 22 union by age 15 Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in BARISAL union before 1 age 18 3 2 0-9% 2 10-19% 20-29% 30-39% 40-49% 50-59% UNFPA + UNICEF implementation 60-69% 70-79% UNFPA implementation 80<% UNICEF implementation 1 Implementation outcome 1 (life skills and education support for girls) 2 Implementation outcome 2 (community dialogue) 3 3 Implementation outcome 3 (strengthening education, 2.05 BIRTHS PER WOMAN health and child protection systems) Total fertility rate (average number of children a woman would have by Note: This map is stylized and not to scale. It does not reflect a position by the end of her reproductive period if her experience followed the currently UNFPA or UNICEF on the legal status of any country or area or the delimitation of any frontiers. -

Booklet, No Cover

Journal of Vol. 6, No. 2 (April 2021) Focus: The Gambia: African 200 Years of Wesleyan Methodist Missions; Morgan, Baker, Fox, Christian Cupidon, Sallah Biography A publication of the Dictionary of African Christian Biography 1 for scriptural, African and Methodism. The researcher thus recommends that the Methodist Church The Gambia should consider inculturating the gospel cognizance of its African traditional and cultural practices with its Methodist heritage for a better expression of Church leadership in the Gambia in the practice of ministry through the rites of passages of its people. Journal of African Christian Park, Matthew James. Heart of Banjul: the history of Banjul, The Gambia, 1816-1965. Ph.D. History, Michigan State University, 2016. Biography URL: https://doi.org/doi:10.25335/M5ZN3F Summary: This dissertation is a history of Banjul (formerly Bathurst), the capital city of The Gambia during the period of colonial rule. It is the first dissertation-length history of the city. “Heart of Banjul” engages with the history of Banjul; the capital city of the Gambia. Based on a close reading of archival and Vol. 6, No. 2 (April 2021) primary sources, including government reports and correspondences, missionary letters, journals, and published accounts, travelers accounts, and autobiographical materials, the dissertation attempts to reconstruct the city and understand how various parts of the city came together out of necessity (though never harmoniously). ©2021 Dictionary of African Christian Biography (DACB.org) 2 75 Sanneh to convert from Islam to Christianity and to pursue a career in academia. The Journal of African Christian Biography was launched in 2016 to complement Here he recounts the unusually varied life experiences that have made him who and make stories from the online Dictionary of African Christian Biography he is today.” (Amazon.com) (www.DACB.org) more readily accessible and immediately useful in African congregations and classrooms.