How the Documentary Film Functions for Bob Dylan Fans Theodore G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACULTY Fl FAMOUS

U.S. POSTAGE BULK RATE zoz<z$ I ft '993fHBMTTW PAID °^yi *a ^t8T PERMIT NO. 33 uomxS uopaoo Port Washington, Wis. FBI DOCUMENTS, pg. 3 + WAYSIDE INN CLOSED, pg. 2 + MANGELSDORFF ON CONCERTS, pg. 7 I THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL Are you one of the angry ones who bangs his nead against the wall while all your friends talk about "peace and love" and "reforming the system"? Then why not send away for our simple aptitude test and see if you might not have the potential to become a real revolutionary. FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL | the only correspondance school of revolution actually taught by real revolutionaries. You'll receive personal attention in your attempts to off the pig and relate through Marxist-Leninist dialectics to the oppreseed masses. Write in today. If you are one of the first 500 people to answer this ad, you'll receive a free AK-47 and 2000 rounds of ammunition. SAMPLE QUESTIONS FROM THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL APTITUDE TEST: Fill in the blanks: Multiple choise: a 1. "Right, The chairman of the standing committee of the Chinese People's 2. "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Mihn/ NLF will surely" Jj|§ Communist Party is; « 1. Blaze Starr | 2. Gregory Peck 3."1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4.../ 3. Tina Turner II We don't want your fucking 4. All of the above FACULTY fL Enver Hoxha Alexander Karenskv Kin Agnew Mario Savio Charles Manson Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Nikita Khrushchev Adam Clayton Powell Tim Leary Vance Packard Bo Bolinski Amelia Earhart William Burroughs John Dos Passos &u FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL 233 E. -

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

Conor Mcpherson's Girl from the North Country

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship English Winter 2018 The aM rriage of Heaven and Hell: Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country Graley Herren Xavier University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Herren, Graley, "The aM rriage of Heaven and Hell: Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country" (2018). Faculty Scholarship. 584. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty/584 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graley Herren • The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: Death and Rebirth in Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country In February 2015, the Irish American playwright John Patrick Shanley con- ducted a revealing interview with his Dublin counterpart Conor McPherson for American Theatre magazine. Asked about his preoccupation with the supernat- ural, McPherson intimated, “I remember when I was a little kid, I was always interested in ghosts and scary things. If I want to rationalize it, it’s probably a search for God.” This quest led him to theater. “There’s something so religious about the theatre,” he stated. We’re all sitting there in the dark, and there’s some- thing about how the stage glows in the darkness, which is such a beautiful pic- ture of human existence. What’s really interesting is the darkness that surrounds the picture. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968)

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Carney, “With Electric Breath” “With Electric Breath”: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968) Court Carney In 1956, police in New Jersey apprehended Woody Guthrie on the presumption of vagrancy. Then in his mid-40s, Guthrie would spend the next (and last) eleven years of his life in various hospitals: Greystone Park in New Jersey, Brooklyn State Hospital, and, finally, the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, where he died. Woody suffered since the late 1940s when the symptoms of Huntington’s disease first appeared—symptoms that were often confused with alcoholism or mental instability. As Guthrie disappeared from public view in the late 1950s, 1,300 miles away, Bob Dylan was in Hibbing, Minnesota, learning to play doo-wop and Little Richard covers. 1 Young Dylan was about to have his career path illuminated after attending one of Buddy Holly’s final shows. By the time Dylan reached New York in 1961, heavily under the influence of Woody’s music, Guthrie had been hospitalized for almost five years and with his motor skills greatly deteriorated. This meeting between the still stylistically unformed Dylan and Woody—far removed from his 1940s heyday—had the makings of myth, regardless of the blurred details. Whatever transpired between them, the pilgrimage to Woody transfixed Dylan, and the young Minnesotan would go on to model his early career on the elder songwriter’s legacy. More than any other of Woody’s acolytes, Dylan grasped the totality of Guthrie’s vision. Beyond mimicry (and Dylan carefully emulated Woody’s accent, mannerisms, and poses), Dylan almost preternaturally understood the larger implication of Guthrie in ways that eluded other singers and writers at the time.2 As his career took off, however, Dylan began to slough off the more obvious Guthrieisms as he moved towards his electric-charged poetry of 1965-1966. -

Things Have Changed Bob Dylan

Things have changed Bob Dylan Gm Gm A worried man with a worried mind I’ve been walkin’ forty miles of bad road Cm Cm No one in front of me and nothing behind If the Bible is right the world will explode Gm Gm D7 There’s a woman on my lap and she’s drinking I’m tryin’ to get as far away from myself as I can D7 champagne Gm Gm Some things are too hot to touch Got white skin, got assassin’s eyes Cm Cm The human mind can only stand so much I’m looking up into the sapphire tinted skies Gm D7 Gm Gm D7 Gm You can’t win with a losing hand I’m well dressed, waiting on the last train Eb D7 Gm Eb D7 Gm Feel like falling in love with the first woman I meet Standin’ on the gallows with my head in the noose Eb D7 Eb D7 Puttin’ her in a wheelbarrow and wheelin’ her down the Any minute now I’m expectin’ all hell to break street loose Gm Gm People are crazy and times are strange People are crazy and times are strange Cm Cm I’m locked in tight, I’m out of range I’m locked in tight, I’m out of range Gm D7 Gm Gm D7 Gm I used to care but - things have changed. I used to care but - things have changed. Gm This place ain’t doin’ me any good Gm Cm I hurt easy, I just don’t show it I’m in the wrong town, I should’ve been in Cm Hollywood You can hurt someone and not even know it Gm Gm D7 Just for a second there I thought I saw something The next sixty seconds could be like an eternity D7 move Gm Gm Gonna get lowdown, gonna fly high Gonna take dancin’ lessons, do the jitterbug rag Cm Cm All the truth in the world adds up to one big lie Ain’t no shortcuts, gonna dress in drag Gm D7 Gm Gm D7 I’m in love with a woman that don’t even appeal to me Only a fool in here would think he got anythin’ to Eb D7 Gm Gm prove Mr. -

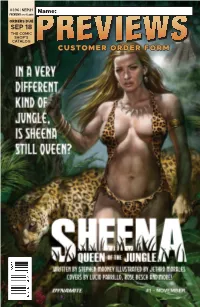

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

On the Road with Janis Joplin Online

6Wgt8 (Download) On the Road with Janis Joplin Online [6Wgt8.ebook] On the Road with Janis Joplin Pdf Free John Byrne Cooke *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893672 in Books John Byrne Cooke 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .93 x 5.43l, 1.00 #File Name: 0425274128448 pagesOn the Road with Janis Joplin | File size: 33.Mb John Byrne Cooke : On the Road with Janis Joplin before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised On the Road with Janis Joplin: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A Must Read!!By marieatwellI have read all but maybe 2 books on the late Janis Joplin..by far this is one of the Best I have read..it showed the "music" side of Janis,along with the "personal" side..great book..Highly Recommended,when you finish this book you feel like you've lost a band mate..and a friend..she could have accomplished so much in the studio,such as producing her own records etc..This book is excellent..0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.By Mic DAs a teen in 1969 and growing up listening to Janis and all the bands of the 60's and 70's, this book was very enjoyable to read.If you ever wondered what it might be like to be a road manager for Janis Joplin, John Byrne Cooke answers it all.Those were extra special days for all of us and John's descriptions of his experiences, helps to bring back our memories.Thank-you John for a very enjoyable book.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian .