Moose Calving Strategies in Interior Montane Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synchronous Fire Activity in the Tropical High Andes: an Indication Of

Global Change Biology Global Change Biology (2014) 20, 1929–1942, doi: 10.1111/gcb.12538 Synchronous fire activity in the tropical high Andes: an indication of regional climate forcing R. M. ROMAN - C U E S T A 1,2,C.CARMONA-MORENO3 ,G.LIZCANO4 ,M.NEW4,*, M. SILMAN5 ,T.KNOKE2 ,Y.MALHI6 ,I.OLIVERAS6,†,H.ASBJORNSEN7 and M. VUILLE 8 1CREAF. Centre for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications, Facultat de Ciencies. Unitat d’ Ecologia Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Barcelona 08193, Spain, 2Institute of Forest Management, Technische Universit€at Munchen,€ Center of Life and Food Sciences Weihenstephan, Hans-Carl-von-Carlowitz-Platz 2, Freising, 85354, Germany, 3Global Environmental Monitoring Unit, Institute for Environment and Sustainability, European Commission, Joint Research Centre, TP. 440 21020, Ispra, Varese 21027, Italy, 4School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford University, South Parks Road, Oxford OX13QY, UK, 5Wake Forest University, Box 7325 Reynolda Station, Winston Salem, NC 27109-7325, USA, 6Environmental Change Institute, School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford University, South Parks Road, Oxford OX13QY, UK, 7College of Life Sciences and Agriculture Durham, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA, 8Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences Albany, University of Albany, Albany, NY, USA Abstract Global climate models suggest enhanced warming of the tropical mid and upper troposphere, with larger tempera- ture rise rates at higher elevations. Changes in fire activity are amongst the most significant ecological consequences of rising temperatures and changing hydrological properties in mountainous ecosystems, and there is a global evi- dence of increased fire activity with elevation. Whilst fire research has become popular in the tropical lowlands, much less is known of the tropical high Andean region (>2000masl, from Colombia to Bolivia). -

GLIMPSES of FORESTRY RESEARCH in the INDIAN HIMALAYAN REGION Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011

Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 i GLIMPSES OF FORESTRY RESEARCH IN THE INDIAN HIMALAYAN REGION Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 Editors G.C.S. Negi P.P. Dhyani ENVIS CENTRE ON HIMALAYAN ECOLOGY G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment & Development Kosi-Katarmal, Almora - 263 643, India BISHEN SINGH MAHENDRA PAL SINGH 23-A, New Connaught Place Dehra Dun - 248 001, India 2012 Glimpses of Forestry Research in the Indian Himalayan Region Special Issue in the International Year of Forests-2011 © 2012, ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development (An Autonomous Institute of Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India) Kosi-Katarmal, Almora All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the copyright owner. ISBN: 978-81-211-0860-7 Published for the G.B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development by Gajendra Singh Gahlot for Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, 23-A, New Connaught Place, Dehra Dun, India and Printed at Shiva Offset Press and composed by Doon Phototype Printers, 14, Old Connaught Place, Dehra Dun India. Cover Design: Vipin Chandra Sharma, Information Associate, ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Cover Photo: Forest, agriculture and people co-existing in a mountain landscape of Purola valley, Distt. Uttarkashi (Photo: G.C.S. Negi) Foreword Amongst the global mountain systems, Himalayan ranges stand out as the youngest and one of the most fragile regions of the world; Himalaya separates northern part of the Asian continent from south Asia. -

DECISION TIME for CLOUD FORESTS No

WATER-RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS OF THE HUMID TROPICS AND OTHER WARM HUMID REGIONS IHP HUMID TROPICS PROGRAMME SERIES NO. 13 IHP Humid Tropics Programme Series No. 1 The Disappearing Tropical Forests DECISION TIME FOR CLOUD FORESTS No. 2 Small Tropical Islands No. 3 Water and Health No. 4 Tropical Cities: Managing their Water No. 5: Integrated Water Resource Management No. 6 Women in the Humid Tropics No. 7 Environmental Impacts of Logging Moist Tropical Forests No. 8 Groundwater No. 9 Reservoirs in the Tropics – A Matter of Balance No.10 Environmental Impacts of Converting Moist Tropical Forest to Agriculture and Plantations No.11 Helping Children in the Humid Tropics: Water Education No.12 Wetlands in the Humid Tropics No.13 Decision Time for Cloud Forests For further information on this Series, contact: UNESCO Division of Water Sciences International Hydrological Programme 1, Rue Miollis 75352 Paris 07 SP France tel. (+33) 1 45 68 40 02 fax (+33) 1 45 67 58 69 PREFACE At a Tropical Montane Cloud Forest workshop held at Cambridge, U.K. in July 1998, 30 scientists, professional managers, and NGO conservation group members representing more than 14 countries and all global regions, concluded that there is insufficient public and political awareness of the status and values of Tropical Montane Cloud Forests (TMCF). The group suggested that a science-based “pop-doc” would be an effective initial action to remedy this. What follows is a response to that recommendation. It documents some of the scientific information that will be of interest to other scientists and managers of TMCF, but not over- whelming for a lay reader who is seeking to become more informed about these remarkable ecosystems. -

Relationships Between Climate, Vegetation, and Energy Exchange Across a Montane Gradient Ray G

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 116, G01026, doi:10.1029/2010JG001476, 2011 Relationships between climate, vegetation, and energy exchange across a montane gradient Ray G. Anderson1,2 and Michael L. Goulden1 Received 8 July 2010; revised 3 November 2010; accepted 3 January 2011; published 10 March 2011. [1] We measured the evaporative fraction (EF) across a semiarid elevation gradient in the San Jacinto and Santa Rosa Mountains of southern California using the Regional Evaporative Fraction Energy Balance platform and four eddy covariance towers. We compared our measurements to precipitation estimates and satellite observations of vegetation indices to assess the seasonal and interannual controls of precipitation and vegetation on surface energy exchanges. Precipitation amount and timing had the largest effect on evaporative fraction, with vegetation having a relatively greater importance at higher elevations than lower elevations. Vegetation cover was linearly related to mean annual EF, but did not predict seasonal variation in EF in most of the study area’s ecosystems. Multiyear vegetation observations show that vegetation density increases in a stepwise pattern with precipitation, probably due to shifts in dominant plant communities. Precipitation is a more important factor in controlling EF than temperature. Possible future climate change, including decreases in precipitation amount and increases in variability, could decrease vegetation cover, thus reducing EF and increasing albedo. Citation: Anderson, R. G., and M. L. Goulden (2011), Relationships between climate, vegetation, and energy exchange across a montane gradient, J. Geophys. Res., 116, G01026, doi:10.1029/2010JG001476. 1. Introduction downstream ecosystems and users [Viviroli and Weingartner, 2004]. Mountains act as “Sky Islands,” providing cooler [2] Patterns of vegetation distribution and energy exchange temperatures and more available water for isolated ecosys- are crucial because they control regional climate [Beringer tems. -

Drivers of Atmospheric Methane Uptake by Montane Forest Soils in the Southern Peruvian Andes

Biogeosciences Discuss., doi:10.5194/bg-2016-16, 2016 Manuscript under review for journal Biogeosciences Published: 27 January 2016 c Author(s) 2016. CC-BY 3.0 License. Drivers of atmospheric methane uptake by montane forest soils in the southern Peruvian Andes †1 †2 3 3 1 1,4 2 S. P. Jones , T. Diem , L. P. Huaraca Quispe , A. J. Cahuana , D. S. Reay , P. Meir and Y. A. Teh 1School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK 5 2Institute of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK 3Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Cusco, Peru 4Research School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia † contributed equally to the work Correspondence to: Sam Jones ([email protected]) 10 Abstract. The soils of tropical montane forests can act as sources or sinks of atmospheric methane (CH 4). Understanding this activity is important in regional atmospheric CH4 budgets, given that these ecosystems account for substantial portions of the landscape in mountainous areas like the Andes. Here we investigate the drivers of CH 4 fluxes from premontane, lower and upper montane forests, experiencing a seasonal climate, in southeastern Peru. Between February 2011 and June 2013, these soils all functioned as net sinks for atmospheric CH4. Mean (standard error) net CH4 fluxes for the dry and wet season -2 -1 -2 -1 15 were -1.6 (0.1) and -1.1 (0.1) mg CH4 - C m d in the upper montane forest; -1.1 (0.1) and -1.0 (0.1) mg CH4 - C m d in -2 -1 the lower montane forest; and -0.2 (0.1) and -0.1 (0.1) mg CH4 - C m d in the premontane forest. -

Impacts of Habitat Degradation on Tropical Montane Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: a Systematic Map for Identifying Future Research Priorities

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW published: 17 December 2019 doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2019.00083 Impacts of Habitat Degradation on Tropical Montane Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Map for Identifying Future Research Priorities Malcolm C. K. Soh 1*, Nicola J. Mitchell 1, Amanda R. Ridley 1, Connor W. Butler 2, Chong Leong Puan 3 and Kelvin S.-H. Peh 2,4 1 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia, 2 School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom, 3 Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Edited by: Malaysia, 4 Conservation Science Group, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom Mark Andrew Adams, Swinburne University of Technology, Australia Tropical montane forests (TMFs) are major centers of evolutionary change and harbor Reviewed by: many endemic species with small geographic ranges. In this systematic map, we Giuliano Maselli Locosselli, University of São Paulo, Brazil focus on the impacts of anthropogenic habitat degradation on TMFs globally. We first Daniel J. Wieczynski, determine how TMF research is distributed across geographic regions, degradation UCLA Department of Ecology and type (i.e., deforestation, land-use conversion, habitat fragmentation, ecological level Evolutionary Biology, United States (i.e., ecosystem, community, population, genetic) and taxonomic group. Secondly, we *Correspondence: Malcolm C. K. Soh summarize the impacts of habitat degradation on biodiversity and ecosystem services, [email protected] and identify deficiencies in current knowledge. We show that habitat degradation in TMFs impacts biodiversity at all ecological levels and will be compounded by climate change. Specialty section: This article was submitted to However, despite montane species being perceived as more extinction-prone due to Tropical Forests, their restricted geographic ranges, there are some indications of biotic resilience if the a section of the journal impacts to TMFs are less severe. -

(Tropical Montane Forest)-Grassland Ecosystem Mosaic of Peninsular India: a Review

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2012, 3, 1632-1639 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2012.311198 Published Online November 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajps) The Shola (Tropical Montane Forest)-Grassland Ecosystem Mosaic of Peninsular India: A Review Milind Bunyan1, Sougata Bardhan2, Shibu Jose2* 1School of Forest Resources and Conservation, Gainesville, USA; 2The Center for Agroforestry, School of Natural Resources, 203 Anheuser-Busch Natural Resources Building, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Email: *[email protected] Received August 17th, 2012; revised September 24th, 2012; accepted October 10th, 2012 ABSTRACT Tropical montane forests (alternatively called tropical montane cloud forests or simply cloud forests) represent some of the most threatened ecosystems globally. Tropical montane forests (TMF) are characterized and defined by the presence of persistent cloud cover. A significant amount of moisture may be captured through the condensation of cloud-borne moisture on vegetation distinguishing TMF from other forest types. This review examines the structural, functional and distributional aspects of the tropical montane forests of peninsular India, locally known as shola, and the associated grasslands. Our review reveals that small fragments may be dominated by edge effect and lack an “interior” or “core”, making them susceptible to complete collapse. In addition to their critical role in hydrology and biogeochemistry, the shola-grassland ecosystem harbor many faunal species of conservation concern. Along with intense anthropogenic pressure, climate change is also expected to alter the dynamic equilibrium between the forest and grassland, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of these ecosystems. Keywords: Shola Forests; Western Ghats; GIS; Biodiversity; Species Composition; Shola Fragments 1. -

Geographic, Environmental and Biotic Sources of Variation in the Nutrient Relations of Tropical Montane Forests

Journal of Tropical Ecology (2016) 32:368–383. © Cambridge University Press 2015. This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. doi:10.1017/S0266467415000619 Geographic, environmental and biotic sources of variation in the nutrient relations of tropical montane forests James W. Dalling∗,†,1, Katherine Heineman∗, Grizelle Gonzalez´ ‡ and Rebecca Ostertag§ ∗ Department of Plant Biology and Program in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology, University of Illinois, 505 S Goodwin Ave, Urbana, IL 61801, USA † Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado Postal 0843–03092, Panama, Republic of Panama ‡ International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Jard´ın Botanico´ Sur, 1201 Calle Ceiba, R´ıo Piedras, Puerto Rico, 00926–1119, USA § Department of Biology, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, 200 W. Kawili Street, Hilo, HI 96720, USA (Received 24 September 2014; revised 9 October 2015; accepted 10 October 2015; first published online 20 November 2015) Abstract: Tropical montane forests (TMF) are associated with a widely observed suite of characteristics encompassing forest structure, plant traits and biogeochemistry. With respect to nutrient relations, montane forests are characterized by slow decomposition of organic matter, high investment in below-ground biomass and poor litter quality, relative to tropical lowland forests. However, within TMF there is considerable variation in substrate age, parent material, disturbance and species composition. Here we emphasize that many TMFs are likely to be co-limited by multiple nutrients, and that feedback among soil properties, species traits, microbial communities and environmental conditions drive forest productivity and soil carbon storage. To date, studies of the biogeochemistry of montane forests have been restricted to a few, mostly neotropical, sites and focused mainly on trees while ignoring mycorrhizas, epiphytes and microbial community structure. -

Chapter 13, Mediterranean California

13 MEDITERRANEAN CALIFORNIA M.E. Fenn, E.B. Allen, L.H. Geiser 13.1 Ecoregion Description mixes depending on elevation and site conditions, but are typically characterized by dense mixed-aged stands Th e Mediterranean California ecoregion (CEC 1997; composed of coniferous (pine [Pinus spp.] and often fi r Fig 2.2) encompasses the greater Central Valley, [Abies spp.] and incense cedar [Calocedrus decurrrens]) Sierra foothills, and central coast ranges of California and broadleaved species (commonly oaks). south to Mexico and is bounded by the Pacifi c Ocean, Sierra Nevada Mountains and Mojave Desert. Th e 13.2 Coastal Sage Scrub ecoregion description is adapted from CEC (1997). It is distinguished by its warm, mild Mediterranean 13.2.1 Ecosystem Description climate, chaparral vegetation, agriculturally productive Coastal sage scrub is a semi-deciduous shrubland that valleys, and a large population (>30 million). Th e Coast occurs in the Mediterranean-type climate of southern Ranges crest at 600 to 1200 m. Th e broad, fl at, Central and central coastal California, extending southward to Valley is drained by the Sacramento and San Joaquin Baja California, Mexico. Th e United States portion of Rivers into the Sacramento Delta and San Francisco coastal sage scrub covers some 684,000 ha (CDFFP Bay. Rugged Transverse Ranges, peaking at 3506 m, 2007). Coastal sage scrub is very diverse. Unfortunately, border the Los Angeles basin. Soils are complex, mostly it is subject to extensive human impacts in rapidly dry, and weakly developed with high calcium (Ca) developing coastal California. Dominant species concentrations. Summers are hot and dry (>18 oC), throughout the range are coastal sagebrush (Artemisia winters are mild (>0 oC) with precipitation from winter californica), Eastern Mojave buckwheat (Eriogonum Pacifi c Ocean storms; coastal fog is common May fasciculatum), sage (Salvia spp.), brittlebush (Encelia through July. -

Downward Shift of Montane Grasslands Exemplifies the Dual Threat of Human Disturbances to Cloud Forest Biodiversity

LETTER LETTER Downward shift of montane grasslands exemplifies the dual threat of human disturbances to cloud forest biodiversity The study by Morueta-Holme et al. (1) provides global warming [at rates similar to those provide, we must find ways to slow or reverse unique and invaluable insight into how tropical observed by Morueta-Holme et al. (1) for the downslope expansion of human-dominated montane ecosystems have responded to climate alpine plant species] (3, 4). In order for grasslands, and thereby allow forest species to change and other anthropogenic disturbances these cloud forest species to continue mi- respond to climate change through upward over the past two-plus centuries. Clearly, one of grating upslope, they will eventually need to migrations. the most important findings of their study is expand their ranges past the current treeline a,b,1 c that many species and ecosystems have shifted into the areas occupied by the Pajonal or Kenneth J. Feeley and Evan M. Rehm their distributions upslope to higher elevations, other montane grasslands. If the lower dis- aDepartment of Biological Sciences, in accord with rising global mean temperatures tributional limit of the grasslands is stable, or International Center for Tropical Botany, (1). Another extremely important finding of the even worse if the grasslands are expanding Florida International University, Miami, FL study that is deserving of extra attention is that into lower elevations as was observed at 33199; bFairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, the high-elevation grasslands of Chimborazo Chimborazo, then cloud forest species will Coral Gables, FL 33156; and cDepartment of Fish, (i.e., the Pajonal) have expanded their distribu- be prevented from shifting the leading edges Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado tions not only upslope but also downslope by of their ranges upslope (2). -

CBD Thematic Report on Mountain Ecosystems

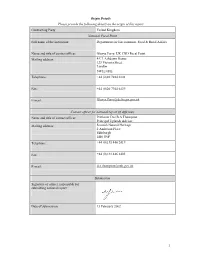

Origin Details Please provide the following details on the origin of this report Contracting Party United Kingdom National Focal Point Full name of the institution: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs Name and title of contact officer: Glenys Parry, UK CBD Focal Point Mailing address: 4/C1 Ashdown House 123 Victoria Street London SW1E 6DE Telephone: +44 (0)20 7944 6201 Fax: +44 (0)20 7944 6239 E-mail: [email protected] Contact officer for national report (if different) Name and title of contact officer: Professor Des B A Thompson Principal Uplands Adviser Mailing address: Scottish Natural Heritage 2 Anderson Place Edinburgh EH6 5NP Telephone: +44 (0)131 446 2419 Fax: +44 (0)131 446 2405 E-mail: [email protected] Submission Signature of officer responsible for submitting national report: Date of submission: 13 February 2002 1 Process Summary Please provide summary information on the process by which this report has been prepared, including information on the types of stakeholders who have been actively involved in its preparation and on material which was used as a basis for the report • Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) requested the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) to lead on preparation of the report. • JNCC created 1st draft response. • JNCC consulted key biodiversity organisations including the Upland lead-co-ordination network of the statutory conservation agencies of the UK (English Nature, Countryside Council for Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage, Environment and Heritage Service)and then edited 1st draft as necessary. • Defra put consultation draft out to wide consultation on UK BAP and CHM websites (www.ukbap.org.uk and www.chm.org.uk ) and through normal consultative channels (statutory, non-governmental and civil society). -

Status, Trends and Future Dynamics of Biodiversity and Ecosystems Underpinning Nature’S Contributions to People 1

CHAPTER 3 . STATUS, TRENDS AND FUTURE DYNAMICS OF BIODIVERSITY AND ECOSYSTEMS UNDERPINNING NATURE’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO PEOPLE 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 STATUS, TRENDS AND CHAPTER FUTURE DYNAMICS OF BIODIVERSITY AND 3 ECOSYSTEMS UNDERPINNING NATURE’S CONTRIBUTIONS CHAPTER TO PEOPLE 4 Coordinating Lead Authors Review Editors: Marie-Christine Cormier-Salem (France), Jonas Ngouhouo-Poufoun (Cameroon) Amy E. Dunham (United States of America), Christopher Gordon (Ghana) This chapter should be cited as: CHAPTER Cormier-Salem, M-C., Dunham, A. E., Lead Authors Gordon, C., Belhabib, D., Bennas, N., Dyhia Belhabib (Canada), Nard Bennas Duminil, J., Egoh, B. N., Mohamed- (Morocco), Jérôme Duminil (France), Elahamer, A. E., Moise, B. F. E., Gillson, L., 5 Benis N. Egoh (Cameroon), Aisha Elfaki Haddane, B., Mensah, A., Mourad, A., Mohamed Elahamer (Sudan), Bakwo Fils Randrianasolo, H., Razafindratsima, O. H., 3Eric Moise (Cameroon), Lindsey Gillson Taleb, M. S., Shemdoe, R., Dowo, G., (United Kingdom), Brahim Haddane Amekugbe, M., Burgess, N., Foden, W., (Morocco), Adelina Mensah (Ghana), Ahmim Niskanen, L., Mentzel, C., Njabo, K. Y., CHAPTER Mourad (Algeria), Harison Randrianasolo Maoela, M. A., Marchant, R., Walters, M., (Madagascar), Onja H. Razafindratsima and Yao, A. C. Chapter 3: Status, trends (Madagascar), Mohammed Sghir Taleb and future dynamics of biodiversity (Morocco), Riziki Shemdoe (Tanzania) and ecosystems underpinning nature’s 6 contributions to people. In IPBES (2018): Fellow: The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Gregory Dowo (Zimbabwe) Africa. Archer, E., Dziba, L., Mulongoy, K. J., Maoela, M. A., and Walters, M. (eds.). CHAPTER Contributing Authors: Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Millicent Amekugbe (Ghana), Neil Burgess Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity (United Kingdom), Wendy Foden (South and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany, Africa), Leo Niskanen (Finland), Christine pp.