Acting in Opera, a Consideration of the Status of Acting in Opera Production and the Effect of a Stanislavski Inspired Rehearsal Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bregenz's Floating Stage

| worldwide | austria PC Control 04 | 2016 Art, technology and nature come together to deliver a great stage experience Advanced stage control technology produces magical moments on Bregenz’s floating stage The seventy-year history of the Bregenz Festival in Austria has been accompanied by a series of technical masterpieces that make watching opera on Lake Constance a world-famous experience. From July to August, the floating stage on Lake Constance hosts spectacular opera performances that attract 7,000 spectators each night with their combination of music, singing, state-of-the- art stage technology and effective lighting against a spectacular natural backdrop. For Giacomo Puccini’s “Turandot”, which takes place in China, stage designer Marco Arturo Marelli built a “Chinese Wall” on the lake utilizing complex stage machinery controlled by Beckhoff technology. | PC Control 04 | 2016 worldwide | austria © Bregenzer Festspiele/Karl Forster © Bregenzer Festspiele/Karl The centerpiece of the floating stage is the round area at its center with an extendable rotating stage and two additional performance areas below it. The hinged floor features a video wall on its under- side for special visual effects, projecting various stage setting images. The tradition of the Bregenz Festival goes back to 1946, when the event started The backdrop that Marco Arturo Marelli designed for “Turandot” consists with a performance of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s musical comedy “Bastian of a 72-meter-long wall that snakes across the stage like a giant dragon. A and Bastienne” on two gravel barges anchored in the harbor. The space on the sophisticated structure of steel, concrete and wood holds the 29,000 pieces barges soon became too small, and the organizers decided to build a real stage in place. -

Saison 2017/18 Établissement Public Salle De Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte

Saison 2017/18 Établissement public Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte Philharmonie Luxembourg Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Saison 2017/18 Nous remercions nos partenaires qui, Partenaires d’événements: en associant leur image à la Philharmonie et à l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg et en soutenant leur programmation, permettent leur diversité et l’accès à un public plus large. Partenaire officiel: Partenaire automobile exclusif: Partenaires média: Sommaire / Inhalt / Content Une extraordinaire diversité 4 Découvrir la musique Musek erzielt (4–8 ans) 216 Bienvenue! 6 L’imagination au pouvoir Philou F (5–9 ans) 218 POST Luxembourg – Partenaire officiel 11 Artiste en résidence: Jean-François Zygel 118 Philou D (5–9 ans) 222 Dating 122 Familles (6–106 ans) 226 Les dimanches de Jean-François Zygel 124 Miouzik F (9–12 ans) 230 Orchestre Lunch concerts 126 Miouzik D (9–12 ans) 232 La beauté d’un cheminement artistique Yoga & Music 128 iPhil (14–18 ans) 236 Directeur musical: Gustavo Gimeno 16 résonances 130 Workshops 240 Grands rendez-vous 20 PhilaPhil 132 Aventure+ 24 Fondation EME 135 Fräiraim & Partenaires L’heure de pointe 30 Fräiraim 246 Fest- & Bienfaisance-Concerten 32 Jazz, World & Chill Solistes Européens, Luxembourg – Retour aux sources Une métaphore musicale de la démocratie Cycle Rencontres SEL A 250 Artiste en résidence: Paavo Järvi 36 Orchestre en résidence: Solistes Européens, Luxembourg – Grands orchestres 40 JALCO & Wynton Marsalis 140 Cycle Rencontres SEL B 252 Grands chefs 44 Jazz & beyond -

Architecture and Space Our Congress Centre in Pictures and Figures Culture Meets Congress and Finds Him Devastatingly Good Looking

Architecture and Space Our congress centre in pictures and figures Culture meets Congress and finds him devastatingly good looking Mrs Culture and Mr Congress appear from opposite sides of the plaza in front of Bregenz Festival House. She is very elegantly dressed, he has more of a sporty look. Both of them are presumably on their way to an event taking place in the centre. As they approach one another it is clear how glad they are to meet again. Culture: Hello! Well now, you look damn good. Congress: You’re not the first person to say so. Culture (a little taken aback): And you’re pretty self-confident with it. Congress: Did I just adopt the wrong tone? Culture : The right tone is more my domain. Congress: In the figurative sense, yes. But technically speaking it’s mine. Sound, lighting, stage set are my responsibilities, and I feel equal to them all. Culture : There seem to be developments in your life which I have never gone through. Congress: That’s right. I’m doing a lot of sport at the moment. Culture: Please don’t do too much. I’m not too keen on muscle-bound types. Congress: Don’t worry, I’m mainly building up my stamina. The body is my house, it’s got to be solid. Culture : The body is the house in which your soul and mind dwell. Congress: Yeah, them too. But without a strong body... Culture : The body matters a lot to me, too, but not in the sense of what’s external. -

The Magic Flute Programme

Programme Notes September 4th, Market Place Theatre, Armagh September 6th, Strule Arts Centre, Omagh September 10th & 11th, Lyric Theatre, Belfast September 13th, Millennium Forum, Derry-Londonderry 1 Welcome to this evening’s performance Brendan Collins, Richard Shaffrey, Sinéad of The Magic Flute in association with O’Kelly, Sarah Richmond, Laura Murphy Nevill Holt Opera - our first ever Mozart and Lynsey Curtin - as well as an all-Irish production, and one of the most popular chorus. The showcasing and development operas ever written. of local talent is of paramount importance Open to the world since 1830 to us, and we are enormously grateful for The Magic Flute is the first production of the support of the Arts Council of Northern Austins Department Store, our 2014-15 season to be performed Ireland which allows us to continue this The Diamond, in Northern Ireland. As with previous important work. The well-publicised Derry / Londonderry, seasons we have tried to put together financial pressures on arts organisations in Northern Ireland an interesting mix of operas ranging Northern Ireland show no sign of abating BT48 6HR from the 18th century to the 21st, and however, and the importance of individual combining the very well known with the philanthropic support and corporate Tel: +44 (0)28 7126 1817 less frequently performed. Later this year sponsorship has never been greater. I our co-production (with Opera Theatre would encourage everyone who enjoys www.austinsstore.com Company) of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore seeing regular opera in Northern Ireland will tour the Republic of Ireland, following staged with flair and using the best local its successful tour of Northern Ireland operatic talent to consider supporting us last year. -

Operaharmony

#OPERAHARMONY CREATING OPERAS IN ISOLATION 1 3 WELCOME TO #OPERA HARMONY FROM FOUNDER – ELLA MARCHMENT Welcome to #OperaHarmony. #Opera Harmony is a collection of opera makers from across the world who, during this time of crisis, formed an online community to create new operas. I started this initiative when the show that I was rehearsing at Dutch National Opera was cancelled because of the lockdown. Using social media and online platforms I invited colleagues worldwide to join me in the immense technical and logistical challenge of creating new works online. I set the themes of ‘distance’ and ‘community’, organised artist teams, and since March have been overseeing the creation of twenty new operas. All the artists involved in #OperaHarmony are highly skilled professionals who typically apply their talents in creating live theatre performances. Through this project, they have had to adapt to working in a new medium, as well as embracing new technologies and novel ways of creating, producing, and sharing work. #OperaHarmony’s goal was to bring people together in ways that were unimaginable prior to Covid-19. Over 100 artists from all the opera disciplines have collaborated to write, stage, record, and produce the new operas. The pieces encapsulate an incredibly dark period for the arts, and they are a symbol of the unstoppable determination, and community that exists to perform and continue to create operatic works. This has been my saving grace throughout lockdown, and it has given all involved a sense of purpose. When we started building these works we had no idea how they would eventually be realised, and it is with great thanks that we acknowledge the support of Opera Vision in helping to both distribute and disseminate these pieces, and also for establishing a means in which audiences can be invited into the heart of the process too . -

Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart

Stephen DODGSON Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart (Chamber opera in four acts) Howden • Wallace • Morris • Ollerenshaw Edgar-Wilson • Brook • Moore • Willcock • Sporsén Perpetuo • Julian Perkins Stephen Act I: By the Banks of the Orwell Act II: The Cobbold Household 1 [Introduction] 2:27 Scene 1: The drawing room at Mrs Cobbold’s house DO(1D924G–20S13O) N ^ 2Scene 1: Harvest time at Priory Farm & You are young (Dr Stebbing) 4:25 3 What an almighty fuss (Luff, Laud) 1:35 Ah! Dr Stebbing and Mr Barry Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart 4 For so many years (Laud, Luff) 2:09 (Mrs Cobbold, Barry, Margaret) 6:54 Chamber opera in four acts (1979) 5 Oh harvest moon (Margaret, Laud) 5:26 * Under that far and shining sky Interlude to Scene 2 1:28 Libretto by Ronald Fletcher (1921–1992), 6 (Laud, Margaret) 1:35 based on the novel by Richard Cobbold (1797–1877) The harvest is ended Scene 2: Porch – Kitchen/parlour – First performance: 8–10 June 1979 at The Old School, Hadleigh, Suffolk, UK 7 (Denton, Margaret, Laud, Labourers) 2:19 (Drawing room Oh, my goodness gracious – look! I don’t care what you think Margaret Catchpole . Kate Howden, Mezzo-soprano 8 (Mrs Denton, Lucy, Margaret, Denton) 2:23 ) (Alice, Margaret) 2:26 Will Laud . William Wallace, Tenor 9 Margaret? (Barry, Margaret) 3:39 Come in, Margaret John Luff . Nicholas Morris, Bass The ripen’d corn in sheaves is born ¡ (Mrs Cobbold, Margaret) 6:30 (Second Labourer, Denton, First Labourer, John Barry . Alistair Ollerenshaw, Baritone Come then, Alice (Margaret, Alice, Laud) 8:46 0 Mrs Denton, Lucy, Barry) 5:10 ™ Crusoe . -

Polish Composer's Masterpiece Premiered After 31 Years

Polish Composer’s Masterpiece Premiered after 31 Years Anna S. Debowska - July 23, 2013 ''The Merchant of Venice'' at the festival in Bregenz (Photo Bregenzer Festspiele / Karl Forster) The real bombshell of the Bregenzer Festspiele in Austria was “The Merchant of Venice.” This was the first time the opera by Andrzej Czajkowski – an eccentric piano genius and survivor of the Warsaw ghetto – has been staged. The outstanding work will have its Polish premiere next year. The classical music festival in Bregenz on Lake Constance is organized with two aims. The festival presents spectacular productions of famous operas on its stage on the water. These are attended by tens of thousands of listeners from Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and England. It also, ambitiously, highlights works by forgotten composers. This two-pronged approach is the brainchild of the English director David Pountney, who has been the artistic director of the Bregenzer Festspiele for nine years. He decided to revive the tradition of the festival, the first edition of which took place in 1946, on the stage built on the lake. He already has staged “Il Travatore,” “Aida,” “Andrea Chenier,” and this year, “The Magic Flute.” He provides light, witty, and cleverly high-tech productions that are open to innovative and quirky ideas. The performances on the water always start in the evening as darkness slowly settles on the lake. Festival organizers use a sound system, but the productions are performed by very talented singers who are able to project in the unusual setting. Every evening, close to seven thousand spectators gather at the floating amphitheater under the night sky. -

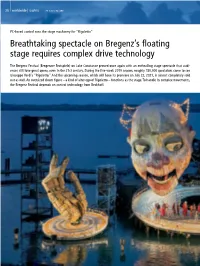

Breathtaking Spectacle on Bregenz's Floating Stage Requires Complex

| 26 worldwide | austria PC Control 02 | 2021 PC-based control runs the stage machinery for “Rigoletto” Breathtaking spectacle on Bregenz’s floating stage requires complex drive technology The Bregenz Festival (Bregenzer Festspiele) on Lake Constance proved once again with an enthralling stage spectacle that audi- ences still love great opera, even in the 21st century. During the five-week 2019 season, roughly 180,000 spectators came to see Giuseppe Verdi’s “Rigoletto.” And the upcoming season, which will have its premiere on July 22, 2021, is almost completely sold out as well. An oversized clown figure – a kind of alter ego of Rigoletto – functions as the stage. To handle its complex movements, the Bregenz Festival depends on control technology from Beckhoff. | PC Control 02 | 2021 worldwide | austria 27 The main With a diameter of 22 meters (72 feet) and a total area cabinet and of 338 square meters (3,638 square feet), the collar the panel for forms the central stage area. Mounted on a seesaw, controlling the the head can be moved across the entire stage. hydraulics are each equipped with a built-in 15-inch CP6602 Panel PC from Beckhoff. © Bregenzer Festspiele/Anja Köhler/andereart.de © Bregenzer Festspiele/Anja | 28 worldwide | austria PC Control 02 | 2021 The “Seebühne Bregenz” (Bregenz floating stage) is famous for its spectacu- and to subject each of them to a safety analysis with regard to their drive lar productions, but Philipp Stölzl’s staging exceeds all past performances in force, load and speed,” explains Wolfgang Urstadt, the technical director of terms of aesthetics as well as technical feasibility. -

In Association With

OVERTURE OPERA GUIDES in association with It is a pleasure to be able to welcome this Overture Opera Guide to The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series un- Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), the eighteenth to be der the editorship of the late Nicholas John in association with published since the series in association with ENO was relaunched English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and even- in 2010. tually included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the Mozart’s penultimate opera – written in the vernacular, with spoken works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They dialogue and music that ranges from the deeply serious to the light- contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a com- hearted – has delighted audiences since its premiere in September 1791 plete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, at a small theatre tucked away in the Viennese suburbs. Exploring as well as bibliographies and discographies. key issues of the Enlightenment, Die Zauberflöte is one of Mozart’s major contributions to the lyric theatre, and no opera company The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available can be without a production of it for long. This guide’s publication again the guides already published in a redesigned format with coincides with a revival at ENO of director Simon McBurney’s new illustrations, many revised and newly commissioned arti- staging of the work, a production whose innovative theatricality has cles, updated reference sections and a literal translation of the won many new admirers for the opera. -

LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Filling the City with Song!

LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Filling the city with song! Festival Programme 2009 The Grammar School at Leeds inspiring individuals is pleased to support the Leeds Lieder+ Festival Our pupils aren’t just pupils. singers, They’re also actors, musicians, stagehands, light & sound technicians, comedians, , impressionists, producers, graphic artists, playwrightsbox office managers… ...sometimes they even sit exams! www.gsal.org.uk For admissions please call 0113 228 5121 Come along and see for yourself... or email [email protected] OPENING MORNING Saturday 17 October 9am - 12noon LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Biennial Festival of Art Song Artistic Director Julius Drake 3 Lord Harewood Elly Ameling If you, like me, have collected old gramophone records from Dear Friends of Leeds Lieder+ the time you were at school, you will undoubtedly have a large I am sure that you will have a great experience listening to this number of Lieder performances amongst them. Each one year’s rich choice of concerts and classes. It has become a is subtly different from its neighbour and that is part of the certainty! attraction. I know what I miss: alas, circumstances at home prevent me The same will be apparent in the performances which you this time from being with you and from nourishing my soul with will hear under the banner of Leeds Lieder+ and I hope this the music in Leeds. variety continues to give you the same sort of pleasure as Lieder singing always has in the past. I feel pretty sure that it To the musicians and to the audience as well I would like to will and that if you have any luck the memorable will become repeat the words that the old Josef Krips said to me right indistinguishable from the category of ‘great’. -

Music by BENJAMIN BRITTEN Libretto by MYFANWY PIPER After a Story by HENRY JAMES Photo David Jensen

Regent’s Park Theatre and English National Opera present £4 music by BENJAMIN BRITTEN libretto by MYFANWY PIPER after a story by HENRY JAMES Photo David Jensen Developing new creative partnerships enables us to push the boundaries of our artistic programming. We are excited to be working with Daniel Kramer and his team at English National Opera to present this new production of The Turn of the Screw. Some of our Open Air Theatre audience may be experiencing opera for the first time – and we hope that you will continue that journey of discovery with English National Opera in the future; opera audiences intrigued to see this work here, may in turn discover the unique possibilities of theatre outdoors. Our season continues with Shakespeare’s As You Like It directed by Max Webster and, later this summer, Maria Aberg directs the mean, green monster musical, Little Shop of Horrors. Timothy Sheader William Village Artistic Director Executive Director 2 Edward White Benson entertained the writer one One, about the haunting of a child, leaves the group evening in January 1895 and - as James recorded in breathless. “If the child gives the effect another turn of There can’t be many his notebooks - told him after dinner a story he had the screw, what do you say to two children?’ asks one ghost stories that heard from a lady, years before. ‘... Young children man, Douglas, who says that many years previously he owe their origins to (indefinite in number and age) ... left to the care of heard a story too ‘horrible’ to admit of repetition. -

Download Bio

Mauricio Trejo www.MauricioTrejo.com [email protected] Mexican-Italian Tenor, Mauricio Trejo, was recently distinguished by the Wagner Society of New York as a promising Wagnerian Tenor. In August 2016 Mr.Trejo received a full scholarship to further and expand hi Wagnerian Tenor repertoire at the Lotte Lehmann Akademie where he also perform concerts in Germany. He has been hailed as "a tenor with a silver bullet top," "the possessor of a clear and powerful instrument of great beauty,” "a revelation." (Luzerner Zeitung) A Sony Classical Recording Artist as one of the original American Tenors. Mauricio has been honored with numerous awards such as the Placido Domingo Scholarship under the auspices of SIVAM, the Panasonic Scholar of the Year, a winner in the International Caruso Competition and a finalist in the Arena di Verona Turandot Competition in the role of Calaf. Mr. Trejo has also been featured in television performances in a nationwide airing on PBS and on TV Azteca in Mexico In May 2017 Mauricio made his debut in the role of Otello by Giuseppe Verdi in New York City. He is also currently expanding his repertory in preparation of Siegfried, Siegmund, Bacchus, and Florestan. Before expanding to the dramatic and Wagnerian repertoire, he performed the leading tenor roles in Tosca, Cavalleria Rusticana, Il Tabarro, Turandot, I Pagliacci, Madama Butterfly, La Boheme, La Traviata, Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor, L'Elisir D'Amore and Der Rosenkavalier. Mauricio's international operatic and concert career has taken him to North, Central and South America, Europe and the Middle East. Performed with companies that include the Opera Orchestra Of New York, Bregenzer Festspiele in Austria, Opernhaus Zurich, Santa Fe Opera, Sarasota Opera, Opera Santa Barbara, Lyric Opera of Vinrginia, New Israeli Opera, The New York Grand Opera, and the Opera Nacional de Panama.